Draft:Imre Lakatos

| Eyes wearing inverted lenses Philosophy of science |

| Foundations |

| Method |

| Conclusions |

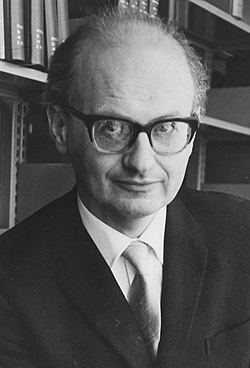

Imre Lakatos (1922–1974) was a philosopher of science and mathematics.

He is known for his criticisms of falsificationism as proposed by Karl Popper, which held that scientific theories can be demarcated from pseudoscientific ones based on whether or not they are falsifiable, as well as for his own proposed solution to the demarcation problem.

Criticism of falsificationism[edit]

Falsificationism holds that science operates by proposing theories, testing them, and rejecting those theories that do not pass the test.[1] Lakatos argued that this principle does not accurately describe how scientists actually operate.[1] If a theory has made many novel successful predictions before, scientists will be loathe to discard it even in light of a failed prediction. For example, the orbit of Mercury deviated from the predictions of Newtonian mechanics enough to have been noticed before the 20th century.[2] These discrepancies were ultimately explained by Einstein's theory of General Relativity,[3] but the discovery of the discrepancy did not lead to the abandonment of Newtonian physics[2] until Einstein's new theory gained acceptance.[3]

Lakatos was not the first to make these criticisms of falsificationism, for example, the Duhem-Quine thesis holds that it is only possible to test scientific theories in groups, and therefore individual theories cannot be falsified.[4]

(Discussion of Thomas Kuhn, paradigms and scientific revolutions)

Lakatos thought that Kuhn's views did not allow for scientific changes to be justified rationally.[5] Lakatos' concept of research programs was intended to allow for scientific change to be justified as rational and progressive, without depending on the "naïve falsificationism" espoused by Popper.

Research programs[edit]

Lakatos argued that scientific theories can be grouped into different research programs. Research programs are composed of a "hard core" of essential propositions, a belt of auxiliary hypotheses that are used to make predictions in combination with the hard core that is open to change, a positive heuristic to modify the auxiliary belt in response to empirical evidence supporting the predictions made using the propositions in the belt, and a negative heuristic to modify the auxiliary belt in response to empirical evidence contradicting the predictions made using the propositions in the belt.[6] Research programs that make successful, novel predictions can be classified as progressive. Research programs that consistently make incorrect predictions will have to modify the auxiliary belt in response to the failures, and can be classified as degenerating.

According to Lakatos, pseudoscientific research programs will tend to degenerate. However, he thought that it was still possible for a research program that has degenerated in the past to become progressive in the future. Because of this, Paul Feyerabend argued that Lakatos's demarcation criteria did not actually allow for any theories to be rejected as pseudoscientific, and was therefore no different from his own position of "epistemological anarchism", which held that there is no useful way to separate science from pseudoscience.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Karl Popper: Philosophy of Science, Brendan Shea, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 LE VERRIER, Urbain Jean Joseph, Rootenberg Rare Books and Manuscripts

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Why Science Needs Theories, Paul Lutus. 2011.

- ↑ Underdetermination of Scientific Theory, Kyle Stanford, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. April 4, 2023.

- ↑ The Popperian Versus the Kuhnian Research Programme, Imre Lakatos, The methodology of scientific research programmes, 1978.

- ↑ A Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes, Imre Lakatos, The methodology of scientific research programmes, 1978.