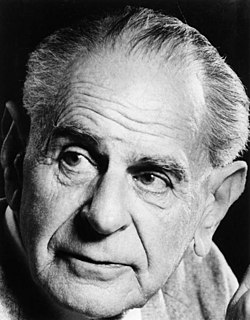

Karl Popper

| Eyes wearing inverted lenses Philosophy of science |

| Foundations |

| Method |

| Conclusions |

“”"Once you pop, you cannot stop"

|

| —Pringles |

Karl Popper (1902–1994) was an important Austrian-British figure in the philosophy of science.[1] He wrote his first book, the Logic of Scientific Discovery on what science is and how it works (in German) in 1934, and translated it to English in the 1950s. He doubled down on these ideas in his more famous work, Conjectures and Refutations. Popper argued that scientific theories can never be proven, merely tested and corroborated. Scientific inquiry is distinguished from all other types of investigation by its testability, or, as Popper put it, by the falsifiability of its theories. Unfalsifiable theories are unscientific precisely because they cannot be tested. His philosophy of science was generally well received by actual scientists.

Additionally, Popper was known for his strong defense of the liberal democratic tradition. He was highly critical of authoritarianism, totalitarianism, superstition, conspiracies, historicism, socialism and dogmatism. Ironically, Popper was somewhat authoritarian and dogmatic in his own personal life.[2]

The criterion of demarcation[edit]

While the logical positivists sought a demarcation between meaningful propositions and gibberish, Popper sought to distinguish science from non-science. It is important to note non-science in the previous statement. Falsifiability, according to Popper, only applies to science or claims with the pretense of being scientific. In this schema, unfalsifiable claims presented as science are in fact pseudoscience. However, not all unfalsifiable claims are pseudoscience; they may simply be unscientific. For example, Popper also believed in the necessity of what he called "metaphysical research programs," which he claimed could contribute to science. Popper initially declared the theory of evolution unscientific, thinking it constituted a metaphysical research program. He later amended his views stating "I have changed my mind about the testability and logical status of the theory of natural selection; and I am glad to have an opportunity to make a recantation".[3][4]

He grounded this distinction in a logical asymmetry between falsification and verification of a universal law; this asymmetry was dependent, in turn, on the equivalence of a universal statement and a negative existential statement. An "existential statement" claims that a state of affairs exists somewhere and sometime, for example "there exists a black swan". A universal statement, such as "all swans are white", is also the denial of an existential statement: in this case a denial that "there exists a non-white swan". The dogmatist need not look further than their first white swan to "prove" their theory that all swans are white to be true.

It is clear that it is much easier to confirm an existential statement than a universal statement. In order to confirm that a black swan exists we would only need to see a black swan. In order to confirm that no black swans exist we would need to trawl through the whole of space and time. Scientists must therefore not be engaged evidence seeking, but openly hostile to their own theories.

Neither can viewing a great many white swans make "all swans are white" any more likely - some people in fact suggest the opposite, as these observations create an illusion of confidence in our hypothesis that can be highly detrimental. Each existential statement can be expressed as “at w,x,y,z point in space time there existed a non-white swan”, for all intents and purposes an infinite number of potentially falsifications and certainly a number we are unable to make a significant dent into by observations. (Bayesians may consider the prior probability of any universal statement to be extremely low as a result of the vast number of opportunities for falsification).

Verification, then, is simply off the menu. Falsification, on the other hand is both possible ("Hey guys! That swan is black!") and useful: we can discard theories we have discovered to be in error. As "verification" is an illusion, science may only advance by means of falsification. It is therefore critical that science does not try to make its theories immune to falsification. For someone to be truly engaged in the scientific method, they need to imagine under what conditions their theories or views could be wrong. What circumstances could invalidate their theories? Most people don't like creating risky tests that could falsify their own beliefs because most people dislike being wrong, have preconceived notions about many things, and suffer from at least some degree of confirmation bias. One of Popper's disciples, Imre Lakatos[5], took these ideas and pushed them further, arguing scientific theories need to make "novel predictions". Anyone can predict that the sun will come up tomorrow or that there will be sand at the beach; scientists need to go further.

Marx, Hegel, and Freud[edit]

Karl Popper's theories about what constitutes true science were in part a reaction to ideas prominent in the early 20th century, Marxism and Freudian psychoanalysis. Both had sizable followings of devotees, both claimed to be scientific, and both were finding evidence everywhere to confirm their theories. Popper found Freudian theory either untestable or unfalsifiable, i.e. Freud could explain psychological problems people had because they were either hugged too much or too little. In Popper's view, Marxism had begun as scientific, but devolved into self-affirming dogma. Do you hate your job? Yes? This proves Marx was right. Do you like your job? Yes? This also proves Marx was right, the bourgeois brainwashed you![6][7] While this doesn't mean that Freud and Marx have nothing to offer us intellectually, it does suggest that people should not uncritically accept any idea that sounds too good to be true. According to Popper, while it is possible that Marx was so right that you literally can't disprove him, it's very unlikely.[citation needed]

As early as in 1937, Popper also had delivered a strike against the core of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's philosophastery, the dialectic, by pointing out:

“”In Hegel's terminology, both the thesis and the antithesis are, by the synthesis, (1) reduced to components (of the synthesis) and are thereby (2) cancelled (or negated, or annulled, or set aside, or put away[8]) and, at the same time, (3) preserved (or stored, or saved, or put away[9]) and (4) elevated (or lifted to a higher level). The italicized expressions are renderings of the four main meanings of the one German word aufgehoben (literally lifted up) of whose ambiguity Hegel makes much use.

|

| —"What is Dialectic", 1937 |

Not surprising that you can pseudo-win any pseudo-reasoning if you act like the philosophical equivalent of a shell game con artist who can answer any attack of the kind "But you said X here!" (meaning: used aufgehoben's meaning X) by stating "Actually, I meant Y!" (some other meaning of aufgehoben).

Which means that at the end, you can use this nice little text to show that not just the texts of those three guys, but anyone who uncritically builds on them, is at best doubtful from a scientific PoV. This includes Johann Gottlieb Fichte,![]() nazis like Heidegger, neocons like Leo Strauss or Francis Fukuyama, fascists like Giovanni Gentile, the various Christian Hegelians, and many more.

nazis like Heidegger, neocons like Leo Strauss or Francis Fukuyama, fascists like Giovanni Gentile, the various Christian Hegelians, and many more.

Political writings[edit]

Politically, Popper was a firm believer in the virtues of liberal democracy and the open society on which he felt it depended. In his book The Open Society and Its Enemies, he primarily criticized Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, Marx (with other targets including the likes of Fichte![]() and Spengler) as having been forerunners of totalitarianism, largely through a shared historicist approach to human events. He believed that historicism, a set of theories claiming to have uncovered laws of historical development, were unscientific and were especially harmful because they substituted alleged historical prophecy for rational decision-making and conscious political value judgments. He argued that the reason why scholars in his time were so reluctant to criticize Plato in particular was due to his status in the canon of the great philosophers of ancient Greece.

and Spengler) as having been forerunners of totalitarianism, largely through a shared historicist approach to human events. He believed that historicism, a set of theories claiming to have uncovered laws of historical development, were unscientific and were especially harmful because they substituted alleged historical prophecy for rational decision-making and conscious political value judgments. He argued that the reason why scholars in his time were so reluctant to criticize Plato in particular was due to his status in the canon of the great philosophers of ancient Greece.

Popper was one of the founders along with Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises and Milton Friedman of the Mont Pelerin Society![]() and remained a key member of the organization for the years to come.[10] He also stated that, without Hayek's interest and support, The Open Society and Its Enemies would not have been published.[11] Popper claimed to be a socialist for "several years" after rejecting Marxism, but ended up abandoning socialism as a whole because it was, according to him, incompatible with individual liberty.[12]

and remained a key member of the organization for the years to come.[10] He also stated that, without Hayek's interest and support, The Open Society and Its Enemies would not have been published.[11] Popper claimed to be a socialist for "several years" after rejecting Marxism, but ended up abandoning socialism as a whole because it was, according to him, incompatible with individual liberty.[12]

Despite seeing the utopian efforts to create true social and economic equality as dangerous and doomed to fail anyway, Popper still supported efforts by the state to reduce and even eliminate what he saw as the worst effects of capitalism, such as the lack of social mobility.[13] Just like he conceded a bit to social democracy, Popper also became more conservative over the years, recognizing that social reform was harder work than it had seemed in the aftermath of World War Two, and that the modest egalitarianism of the European welfare state was perhaps as much as could reasonably be hoped for.[13][14]

Quotes[edit]

On the topic of Christians who feel they are somehow superior to those with different beliefs:

“”Their thoughts are endowed ... with 'mystical and religious faculties' not possessed by others, and who thus claim that they "think by God's grace". This claim with its gentle allusion to those who do not possess God's grace, this attack upon the potential spiritual unity of mankind, is, in my opinion, as pretentious, blasphemous and anti-Christian, as it believes itself to be humble, pious, and Christian.

|

| —The Open Society and Its Enemies (II,242/3) |

On how science develops theories:

“”Science must begin with myths, and with the criticism of myths.

|

| —Ch. 1 Conjectures and Refutations, Section VII[15] |

On tolerance:

“”Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them… We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.

|

| —The Open Society and Its Enemies, Vol. 1, Notes to the Chapters: Ch. 7, Note 4 |

On "great men":

“”(I)f our civilisation is to survive, we must break with the habit of deference to great men.

|

| —The Open Society and Its Enemies (I,vii) |

On conspiracies:

“”The conspiracy theory of society is just a version of this theism, of a belief in gods whose whims and wills rule everything. It comes from abandoning God and then asking: ‘Who is in his place?’ His place is then filled by various powerful men and groups—sinister pressure groups, who are to be blamed for having planned the great depression and all the evils from which we suffer

|

| —"Popper, K. (2006). The conspiracy theory of society. Conspiracy theories: The philosophical debate, 13-16." |

On socialism and egalitarianism:

“”I remained a socialist for several years, even after my rejection of Marxism; and if there could be such a thing as socialism combined with individual liberty, I would be a socialist still. For nothing could be better than living a modest, simple, and free life in an egalitarian society. It took some time before I recognized this as no more than a beautiful dream; that freedom is more important than equality; that the attempt to realize equality endangers freedom; and that, if freedom is lost, there will not even be equality among the unfree.

|

| —Popper, K. (2005). Unended Quest - an Intelectual Biography, 36 |

Selected works[edit]

- The Logic of Scientific Discovery

- The Open Society and Its Enemies

- The Poverty of Historicism

- Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge

- "What is Dialectic?"

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Entry in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- "Science as Falsification" - an excerpt from Conjectures and Refutations (1963) by Karl R. Popper. pp. 33-39.

- The Open Society and Its Enemies

- Popper, Science, and Pseudoscience. Crash Course Philosophy.

References[edit]

- ↑ Karl Popper at Philpapers.org

- ↑ The paradox of Karl Popper

- ↑ Sonleitner, Frank J., What did Karl Popper really said about evolution? December 15, 2008

- ↑ Elgin, M., & Sober, E. (2017). Popper’s Shifting Appraisal of Evolutionary Theory. HOPOS: The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science, 7(1), 31-55.

- ↑ https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lakatos/

- ↑ Popper on the demarcation of science vs pseudoscience (Video 1 of 3)

- ↑ Popper on Observation and Hypotheses (Video 1 of 3)

- ↑ As in, "on the garbage heap"

- ↑ As in, "for later use"

- ↑ Dieter., Mirowski, Philip. Plehwe,. The Road from Mont Pèlerin : the Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, With a New Preface. ISBN 978-0-674-49511-1. OCLC 984687851.

{{cite book}}: Text "p.21" ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ THE OPEN SOCIETY AND ITS ENEMIES. Princeton University Press. 2020-09-15. pp. xxxv. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Unended quest : an intellectual autobiography. Collins. 1976. p. 36. ISBN 0-00-634116-0. OCLC 1112564799.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 13.0 13.1 Karl Popper: Political Philosophy

- ↑ Ryan, Alan. "INTRODUCTION". The Open Society and Its Enemies, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020, pp. XIX. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691212067-002

- ↑

Popper, Karl (2014) [1963]. "VII". Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge Classics (revised ed.). London: Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 9781135971304. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

Thus science must begin with myths, and with the criticism of myths; neither with the collection of observations, nor with the invention of experiments, but with the critical discussion of myths, and of magical techniques and practices.