Stanford prison experiment

| Tell me about your mother Psychology |

| For our next session... |

| Popping into your mind |

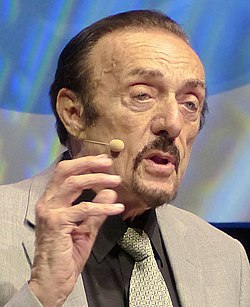

The Stanford prison experiment (SPE) is the common name for a psychological study done in 1971 at Stanford University by psychology professor Philip Zimbardo![]() (1933–2024). Essentially, it placed students into the roles of guards and prisoners and immersed them in the roles by putting them in a setup designed to look like a prison. It was originally meant to run for 14 days, but was cut short at the request of Zimbardo's then-girlfriend.[1][2][3]

(1933–2024). Essentially, it placed students into the roles of guards and prisoners and immersed them in the roles by putting them in a setup designed to look like a prison. It was originally meant to run for 14 days, but was cut short at the request of Zimbardo's then-girlfriend.[1][2][3]

The SPE has been called one of the most famous psychology experiments,[4] and it has been argued that it is the most famous psychology experiment.[5] Alas, fame does not translate into quality.

The study was deeply flawed both ethically (though it met ethical standards at the time[6]) and methodologically. In response to criticism that it was not an experiment, Zimbardo has said:

“”It depends what you mean by scientific value. From the beginning, I have always said it's a demonstration. The only thing that makes it an experiment is the random assignment to prisoners and guards, that's the independent variable. There is no control group. There's no comparison group. So it doesn't fit the standards of what it means to be "an experiment." It's a very powerful demonstration of a psychological phenomenon, and it has had relevance.

So, yes, if you want to call it anecdote, that's one way to demean it. If you want to say, "Is it a scientifically valid conclusion?" I say … it doesn’t have to be scientifically valid. It means it's a conclusion drawn from this powerful, unique demonstration. |

| —Zimbardo[7] |

Despite Zimbardo's claim that he has always called it a demonstration, he has continuously and erroneously called it an experiment, from the initial publications in 1971[8] and 1973[9] up through his current website.[10]

Methodological issues[edit]

The study was plagued by methodological problems, including the following:

- No control group

- Small sample size

- The subjects were all college students from similar backgrounds (middle class and mostly white)

- No replication — the study was essentially an anecdote

- Hawthorne effect — study subjects may change their behavior if they are aware they are being observed (the study subjects knew that they were being watched[11])

- According to Thibault Le Texier's review of the study's archives, "The guards knew what results the experiment was supposed to produce … far from reacting spontaneously to this pathogenic social environment, the guards were given clear instructions for how to create it … the experimenters intervened directly in the experiment, either to give precise instructions, to recall the purposes of the experiment, or to set a general direction … in order to get their full participation, Zimbardo intended to make the guards believe that they were his research assistants."[12]

- Films of the study showed evidence that the observers directly influenced the behavior of the subjects during the study.[13][14]

- One of the students chosen as a guard had been involved in drama productions and created a persona during the study:

“”What came over me was not an accident. It was planned. I set out with a definite plan in mind, to try to force the action, force something to happen, so that the researchers would have something to work with. After all, what could they possibly learn from guys sitting around like it was a country club? So I consciously created this persona. I was in all kinds of drama productions in high school and college. It was something I was very familiar with: to take on another personality before you step out on the stage. I was kind of running my own experiment in there, by saying, "How far can I push these things and how much abuse will these people take before they say, 'knock it off?'" But the other guards didn't stop me. They seemed to join in. They were taking my lead. Not a single guard said, "I don't think we should do this."

|

| —Dave Eshelman[15] |

Crucially, the results claimed by the study have not been replicated,[16][17][18] and the study is part of the broader crisis in psychology, where well-known psychology studies frequently fail to be reproduced.[19][20]

Ethical issues[edit]

The study had been approved by Stanford's Human Subjects Review Committee before it commenced,[6][21] and was subsequently reviewed by the American Psychological Association in 1973, which concluded "that all existing ethical guidelines had been followed."[6] The controversy surrounding the study, however, led the American Psychological Association to adopt more stringent guidelines for human studies.[22] By modern ethical standards, the potential benefits of the experiment would have to outweigh any potential psychological harm to the subjects.

It is likely that during the SPE, false imprisonment![]() [note 1] occurred, as a former Santa Clara County Deputy District Attorney confirmed.[24] Douglas Korpi, one of the prisoners, later claimed that he faked a mental breakdown in order to get out of the SPE.[24] There was apparently no way for prisoners to leave the experiment short of having a physical or mental health crisis.[24] Zimbardo later lied that all a research subject had to do was state, "I quit the experiment." in order to get out, as stated in the informed consent forms that they signed. However, the on-line informed consent forms that Zimbardo himself posted have no such information.[24][25] Korpi also stated that his greatest regret in life was failing to sue Zimbardo.[24] Korpi also accused Zimbaro of stalking him after the experiment.[24]

[note 1] occurred, as a former Santa Clara County Deputy District Attorney confirmed.[24] Douglas Korpi, one of the prisoners, later claimed that he faked a mental breakdown in order to get out of the SPE.[24] There was apparently no way for prisoners to leave the experiment short of having a physical or mental health crisis.[24] Zimbardo later lied that all a research subject had to do was state, "I quit the experiment." in order to get out, as stated in the informed consent forms that they signed. However, the on-line informed consent forms that Zimbardo himself posted have no such information.[24][25] Korpi also stated that his greatest regret in life was failing to sue Zimbardo.[24] Korpi also accused Zimbaro of stalking him after the experiment.[24]

“”We unlisted the number and [Zimbardo] figured out our unlisted number. It was just bizarre. I would always tell him, 'I don't want to have anything to do with the experiment anymore.' [Zimbardo:] 'But Doug, but Doug, you’re so important! And I'll give you lots of referrals!' [Korpi:] 'Yeah, I know Phil, but I testify in court now and it's embarrassing how I was. I don't want to have that be a big public thing anymore.' But Phil just couldn't hear that I didn't want to be involved. This went on for years.

|

| —Douglas Korpi[24] |

Zimbardo's conclusion[edit]

Zimbardo has responded to most of his critics, and has reiterated his belief that the SPE's conclusions are correct:[26]

“”In this response to my critics, I hereby assert[note 2] that none of these criticisms present any substantial evidence that alters the SPE's main conclusion concerning the importance of understanding how systemic and situational forces can operate to influence individual behavior in negative or positive directions, often without our personal awareness.

|

| —Zimbardo |

The crux of the problem with this, though, is that Zimbardo has rejected the need for scientific validity (or presumably of logical validity as well). Validity is when the conclusion follows from the premises (in logic), or when the conclusions follow from the methods and results (in scientific experiments). Zimbardo is essentially making a fallacious argument — argument by assertion, i.e., it looks like what Zimbardo observed, or what he thought was common sense, therefore it is so.

Repercussions[edit]

A 2014 survey of introductory social psychology textbooks found that 3 of 10 textbooks studied did not include the SPE at all. Of those that did include the SPE, "the majority of the texts providing coverage either provided no or minimal coverage of the criticisms."[4][27]

Analogies between the SPE and real-world events (e.g., Abu Ghraib[28] and the Rwandan Genocide[29]) have continued to be drawn despite the serious flaws of the SPE. Zimbardo has written about similarities between Abu Ghraib and the SPE in his book The Lucifer Effect,[30] and he served as a defense team expert witness for one of the prison guards who was charged for crimes at Abu Ghraib.[28]

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- See the Wikipedia article on Asch conformity experiments. — the earliest of the conformity studies

- The Stanford Prison Experiment — a 2015 docudrama based on the original study

- Philip Zimbardo: The Lucifer Effect Understanding How Good People Turn Evil (Nov 14, 2014) YouTube

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 8. Conclusion Stanford Prison Experiment.

- ↑ The Stanford Prison Experiment: Still powerful after all these years (1/8/97) Stanford News.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Christina Maslach.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Coverage of the Stanford Prison Experiment in Introductory Social Psychology Textbooks by Richard Griggs & George I. Whitehead (2014) Teaching of Psychology 41(4):318-324. 10.1177/0098628314549703.

- ↑ 10 Psychological Studies That Will Change What You Think You Know About Yourself by Carolyn Gregoire (10/18/2013 08:22am EDT | Updated December 6, 2017) Huffington Post.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Frequently Asked Questions Stanford Prison Experiment.

- ↑ Philip Zimbardo defends the Stanford Prison Experiment, his most famous work: What's the scientific value of the Stanford Prison Experiment? Zimbardo responds to the new allegations against his work. by Brian Resnick (Jun 28, 2018, 7:50am EDT) Vox.

- ↑ Statement of Philip G. Lombardo, Ph. D., Professor of Psychology, Stanford University (October 25, 1971) Congressional Record, Serial No 15, pp. 110-157, via Stanford Prison Experiment. "A very brief description of the experiment…" (p. 111).

- ↑ A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison by Craig Haney, Curtis Banks & Philip Zimbardo (1973) International Journal of Criminology and Penology 1:69-97. "Interpersonal dynamics in a prison environment were studied experimentally…"

- ↑ Stanford prison experiment by Philip G. Zimbardo.

- ↑ The Real Lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment by Maria Konnikova (June 12, 2015) The New Yorker.

- ↑ Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment by Thibault Le Texier (2019) American Psychologist 74(7):823–839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401.

- ↑ New evidence shows Stanford Prison Experiment conclusions "untenable": Archival recordings show one of the world's most famous psychology experiments was poorly designed – and its use to justify brutality baseless. by Andrew Masterson (09 July 2018) Cosmos (archived from July 14, 2018).

- ↑ Rethinking the 'nature' of brutality: Uncovering the role of identity leadership in the Stanford Prison Experiment by S. Haslam et a. (June 27, 2018) PsyArXiv Preprints.

- ↑ The Menace Within: What happened in the basement of the psych building 40 years ago shocked the world. How do the guards, prisoners and researchers in the Stanford Prison Experiment feel about it now? (July/August 2011) Stanford Magazine.

- ↑ The BBC Prison Study

- ↑ The ideas interview: Alex Haslam: Abu Ghraib need not have happened and the Stanford prison experiment got it wrong. by John Sutherland (31 Oct 2005 03.55 EST) The Guardian.

- ↑ Learning from the Experiment: Steve Reicher and Alex Haslam recently conducted a major study with the BBC (The Experiment). Pam Briggs (Chair of the British Psychological Society Press Committee) sought their views on the ethical and practical issues. First published in the July 2002 edition of The Psychologist (archived from February 21, 2009).

- ↑ Psychology results evaporate upon further review: Surprising reports, findings with marginal statistical significance least likely to be reproduced, study concludes by Bruce Bower (2:00pm, August 27, 2015) Science News.

- ↑ Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science by B. A. Nosek et al. 28 August 2015: Vol. 349 no. 6251 Science DOI: 10.1126/science.aac4716.

- ↑ Human Subjects Research Review Committee (Non-Medical) (July 31, 1971)]

- ↑ The Stanford Prison Experiment by Saul McLeod (updated 2020) Simply Psychology.

- ↑ Sentencing and Punishment for PC 236 Violation Wallin & Klarich.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 The Lifespan of a Lie: The most famous psychology study of all time was a sham. Why can’t we escape the Stanford Prison Experiment? by Ben Blum (Jun 7, 2018·29) Medium.

- ↑ Consent: Prison Life Study by Dr. Zimbardo (August 1971) Stanford Prison Experiment.

- ↑ Statement from Philip Zimbardo Stanford Prison Experiment.

- ↑ Intro to psychology textbooks gloss over criticisms of Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment by Eric W. Dolan (September 7, 2014) PsyPost.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Abu Ghraib: The Real Stanford Prison Experiment by Peter Kinderman (c. 2020) Psych Liverpool.

- ↑ Wicked within by Alan Zarembo (April 22, 2007 12 AM PT) Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil by Philip Zimbardo (2007) Random House, Rider. ISBN 9781400064113.