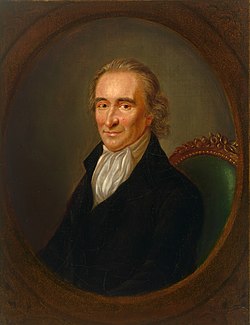

Thomas Paine

| Thinking hardly or hardly thinking? Philosophy |

| Major trains of thought |

| The good, the bad, and the brain fart |

| Come to think of it |

Thomas Paine (1737–1809), or "that dirty little atheist" to Theodore Roosevelt, was the man most responsible for the folk of the United States deciding to fight for their independence.

Many would argue that he was the Founding Father of the nation; to quote John Adams (not exactly the biggest Paine admirer[1]), "Without the pen of Paine, the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain." Hell, he fucking named the country.[1]

He advocated strongly and eloquently for independence from the monarchy, which none of his contemporaries envisioned originally (and had not changed their minds until they heard his arguments for it). He wrote the smash hit, Common Sense, which gained popularity even among Europeans, and gave the money to the Continental Army. He wrote and sent his second smash hit, The American Crisis, that convinced Franco-Spanish military might and Dutch finance to help win the war for the colonies. He was one of the first to call for total abolition of slavery and the death penalty. He was an ardent supporter of secularism, and famously turned his pen against religious authority in The Age of Reason. The secularism would later be codified into the Constitution under the idea of separation of church and state.

After the Revolution, he harshly opposed any attempt at barring non-landowners from voting, warning that this was tyranny-in-waiting and rationalizing that praising republican values but not letting everyone be represented was utterly hypocritical. He turned his pen in defense of liberty — rather an attack on Edmund Burke — in The Rights of Man, which in turn inspired Mary Wollstonecraft — the mother of feminism — to pen The Rights of Woman. Even before Common Sense, Paine wrote an article criticizing the ways in which women are oppressed in society and defending their rights at a time when most men thought they had none. He pushed for a centralized, egalitarian government that respected and upheld all rights to all citizens.[2]

While some of his quotes make him beloved by libertarians, he also wrote in the pamphlet Agrarian Justice of the need for all people to be given a small sum by the government, and then to be provided for in their old age, which was considered "generations ahead of its time."[3] Paine proposed a form of estate tax in order to implement this.[4]

Paine was also an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution; The Rights of Man was actually a response to Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, which was sharply critical of the uprising [5]. Paine had moved back to England in 1787[note 1], and his advocacy for popular sovereignty and uprisings at a time when an increasingly violent uprising was actually happening in nearby France caused a bit of concern in the British government- which then banned The Rights of Man, and attempted to arrest him for treason. Before he could be arrested, he fled to Revolutionary France in 1792.[6] Due to his connections to both the American and French revolutions, he was greeted as a hero in France, awarded honorary citizenship, and even elected to a seat in the National Assembly[7]. However, he came to be associated with the Girondin faction in the political struggles that were heating up[note 2], and vocally opposed the French king's execution. At the end of 1793 he was stripped of his seat in the Assembly and imprisoned[8].

While in prison awaiting his expected guillotining, he wrote The Age of Reason, which didn't exactly win him any friends[9][note 3]. While many Founding Fathers were Deists, most Americans were not, especially since at the time religious fervor was on the rise in the fledgling United States, the so-called Second Great Awakening. He became badly ill, and was only spared execution by sheer luck[10]. A few days after the date he was supposed to be executed, the mastermind of the violence, Maximilien Robespierre, was himself executed, and Paine was spared having a date with Madame Guillotine. President Washington's envoy to Paris, Gouverneur Morris, was a critic of Paine and refused to offer any help[11]; he mocked The Age of Reason by writing to Washington "Thomas Paine is in prison, where he amuses himself with publishing a pamphlet against Jesus Christ"[12].

Eventually, James Monroe became the American envoy to Paris, and was able to get Paine released from prison after nearly a year, and Paine became... a bit unhinged. Because Washington's envoy hadn't tried to help him, Paine, who had written glowingly in support of his close friend Washington during the American war, saw this as an abject betrayal. So in 1796, he burned that bridge by writing an open letter sharply attacking Washington for, among other things, being both unworthy of his war hero status, and a treacherous charlatan who only won the War for Independence due to French assistance[13]. After the slightly more sympathetic Thomas Jefferson finally became president, Paine moved back to the United States in 1802, having become disillusioned with Napoleon, despite his early support for the dictator[14].

He quietly lived out the rest of his life in New York City, dying in 1809. Due to his attack on Washington (who was already revered as a hero to the young nation), his support of the French Revolution even after it turned violent[note 4], and alienating religious Americans with The Age of Reason, he had few friends left at the end of his life. His funeral was attended by only six people, and a newspaper summarized his life as having done "some good and much harm"[15]

Abuse

In full irony, a particularly virulent madman has styled himself the reincarnation of Thomas Paine.[16]

Famous quotes

“”Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one.

|

| —Thomas Paine |

“”[C]reate a national fund, out of which there shall be paid to every person, when arrived at the age of twenty-one years, the sum of fifteen pounds sterling per annum, as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property. And also, the sum of ten pounds per annum, during life, to every person now living, of the age of fifty years, and to all others as they shall arrive at that age.

|

| —Thomas Paine |

“”It is the living, and not the dead, that are to be accommodated. When man ceases to be, his power and his wants cease with him; and having no longer any participation in the concerns of this world, he has no longer any authority in directing who shall be its governors, or how its government shall be organised, or how administered.

|

| —Thomas Paine |

“”Without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain.

|

| —John Adams |

External links

References

- ↑ Is it true that Thomas Paine first coined the phrase, "The United States of America?" Thomas Paine National Historical Association

- ↑ History of the Separation of Church and State in America by R. G. Price (March 27, 2004) rationalrevolution.net

- ↑ Taking Liberties: The struggle for Britain's freedoms and rights, The British Library (archived copy from March 21, 2016).

- ↑ Thomas Paine — Agrarian Justice Social Insurance History (Social Security Adminsitration) (archived copy from February 10, 2017). "Various methods may be proposed for this purpose, but that which appears to be the best… is at the moment that property is passing by the death of one person to the possession of another. In this case, the bequeather gives nothing: the receiver pays nothing. The only matter to him is that the monopoly of natural inheritance, to which there never was a right, begins to cease in his person."

- ↑ The riposte of Thomas Paine to Edmund Burke: “Rights of a Man”

- ↑ The free speech battle that forced Britain’s 18th-century radicals to flee

- ↑ Address to the People of France

- ↑ Thomas Paine at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Age of Reason by Thomas Paine at USHistory.org

- ↑ Thomas Paine’s Revolutionary Reckoning

- ↑ Thomas Paine and Robespierre: the Terror of the Rights of man

- ↑ No Sunshine Patriot

- ↑ Letter to George Washington, president of the United States of America

- ↑ Thomas Paine : enlightenment, revolution, and the birth of modern nations by Craig Nelson

- ↑ Thomas Paine on American Battlefield Trust

- ↑ Glenn Beck is Thomas Paine, Except for Everything by Chris Kelly (05/16/2009 05:12 am ET | Updated May 25, 2011) The Huffington Post.

Notes

- ↑ Paine had invented a new kind of bridge, and returned to England to try to sell it. He was still there when the French Revolution kicked off, after which he shifted gears and became a vocal supporter of it.

- ↑ The two main political factions in France at the time were the moderate Girondins and the radical Montagnards. In mid 1793, the Montagnards were able to ban the Girondins from the National Assembly, and the so-called "Reign of Terror" really got underway.

- ↑ It was released in three parts. The first two, published in 1794 and 1795, sold fairly well, but they came at a time when the French Revolution had become embroiled in the Reign of Terror, and France was at war with several countries- so supporters like Paine were viewed with suspicion outside of France. He did not publish the third until 1807, despite advice from Thomas Jefferson not do so. It did not sell well and he suffered a backlash.

- ↑ The more conservative Federalist party, led by the likes of Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and John Adams, dominated American politics until 1816, and turned against the French Revolution early. Their opposition made them opponents of supporters like Paine, Jefferson, and James Madison.