John Adams

“”Mr. Adams meant well for his country, was always an honest man, often a wise one, but sometimes and in some things, absolutely out of his senses.

|

| —Benjamin Franklin[1] |

| —John Adams on rationality[2] |

| God, guns, and freedom U.S. Politics |

| Starting arguments over Thanksgiving dinner |

| Persons of interest |

John Adams (October 30, 1735–July 4, 1826) is an American Founding Father who served as George Washington's Vice President from 1789 to 1797 and as the second President of the United States of America for a single term from 1797 to 1801, after a bitterly contested election. In terms of party affiliation, Adams was the only Federalist to serve as President (though Washington was one in all but name). Adams ran for re-election in 1800 but was defeated by Thomas Jefferson in the latter's "Revolution of 1800."

Adams was a lawyer and political activist prior to the American Revolution, and he was a firm champion of the presumption of innocence in court. After the so-called "Boston Massacre", he defied the anti-British colonists by representing the British perpetrators as their defense, and he successfully won acquittal for most of the soldiers. He then served as a delegate from Massachusetts in the Continental Congress, where he assisted in drafting the Declaration of Independence in 1776. During the final phases of the war, he was part of the American diplomatic team which secured peace and independence from the British Empire in 1783.

During the era of the Articles of Confederation, Adams wrote the Constitution of Massachusetts, which is the world's oldest functioning constitution.[3] Its provisions were influential at the Continental Congress and helped shape the US Constitution. Adams then won the contested Vice Presidential race to serve alongside George Washington, although he was marginalized and rarely a part of actual decision-making.

Adams then won the presidency for himself in 1796, which was a bitter contest against his rival Thomas Jefferson amid foreign interference from France. As a Federalist, Adams faced angry criticism from Jefferson's Democratic-Republican party throughout his single term in office. His fellow Federalist Alexander Hamilton also formed a rivalry with Adams, leaving the president politically weak. The Alien and Sedition Acts and the undeclared Quasi-War with France also did much to hurt him politically. He was defeated by Jefferson in the 1800 election amid charges of incompetence and despotism. On the nice side, though, Adams expanded the US Navy, avoided war with England and France, and made peace with France. Later in life, he and Jefferson eventually reconciled their differences and repaired their friendship. Both men died within five hours of each other on July 4th, 1826. Humorously, Adams's last words are said to be "Thomas Jefferson survives," even though Jefferson had died several hours earlier.[4]

Law career and activism[edit]

“”It is more important that innocence be protected than it is that guilt be punished, for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world that they cannot all be punished. But if innocence itself is brought to the bar and condemned, perhaps to die, then the citizen will say, “whether I do good or whether I do evil is immaterial, for innocence itself is no protection,” and if such an idea as that were to take hold in the mind of the citizen that would be the end of security whatsoever.

|

| —John Adams on the presumption of innocence.[5] |

Adams began his career as a Boston trial lawyer in 1758. Adams started slow and actually lost his first two cases since he had focused his studies on classical law rather than the more relevant Massachusetts law.[6] During this time, he successfully courted and married Abigail Smith (his third cousin),[7] who remained his wife and eventually became the first First Lady to live in the White House.

John soon became a brilliant lawyer with a special passion for the presumption of innocence. He kept a diary of every case he handled, using it as a tool to improve his trial techniques as he went forward.[8] From 1765, Adams became an activist for the economic interests of the American colonies. He wrote in newspapers to oppose legislation like the Stamp Acts, and he even joined the Sons of Liberty organization, which was headed by his cousin Samuel Adams.[9]

As a member of the Sons of Liberty, he provided legal counsel to John Hancock when Hancock's ship was seized for smuggling wine. His legal defense successfully got the case dropped on the basis that taxation without representation in Parliament was illegitimate.[10] Adams' fame soared even higher when he defended three seamen accused of murdering a British naval officer who tried to impress them into service in the Rex v. Corbet case.[11]

Boston Massacre defense[edit]

“”The Part I took in Defence of Cptn. Preston and the Soldiers, procured me Anxiety, and Obloquy enough. It was, however, one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested Actions of my whole Life, and one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently.

|

| —John Adams' diary entry recollecting the trial.[12] |

In 1770, a mob accosted a group of British soldiers, and the British troops' defense killed five people.[13] The event infuriated the people of Boston, who demanded that the perpetrators be executed. Revolutionary Paul Revere created an illustration of the event which was designed as propaganda to further stir up public sentiment against the British soldiers.[14] The British soldiers became the most hated people in Boston.

The British and their officer, Captain Preston, were completely unable to find legal representation for themselves until John Adams finally agreed to take their case. Despite being a firm Patriot, he believed that it was essential that the British soldiers get the best possible legal defense and a fair trial, as anything else would convince the British that Boston could not be trusted with its own legal affairs.[15] The trials took place amid increased mob activity and threats of lynching the British soldiers. Captain Preston was acquitted by the jury in a six-day trial after the prosecution failed to show sufficient evidence that he had given any orders to fire.[15]

The trial of the eight other soldiers together was much more difficult, since Preston's acquittal made it appear that they had been responsible. They were also tried in a group, meaning that if just one soldier was found guilty of murder, then all would be executed.[15] Adams' defense rested on the fact that the soldiers had been attacked by a mob and therefore had the right to defend themselves.[16] Adams' case was also greatly helped by the testimony of wounded victim Patrick Carr, who testified through his doctor that the mob had indeed attacked the soldiers and that Carr didn't blame them for fighting back.[16]

The jury ultimately acquitted six soldiers of all charges and found two men guilty of manslaughter. His political genius also came into play here, as he kept his reputation as a Patriot by telling the jury and people of Boston that the soldiers should not be blamed for the bad policies of London.[16] This helped keep him popular with Bostonians.

Political career[edit]

Continental Congress[edit]

After the Boston Tea Party, Parliament passed the so-called "Intolerable Acts" to punish the Massachusetts colonists for their defiance.[17] In response, American colonists convened the First Continental Congress, with Massachusetts electing to send John Adams as part of their delegation. Adams quickly aligned himself with the radical faction in the body, as while he did think it was best to remain with the British, he didn't feel any special need to be conciliatory towards them.[18] Adams' most passionate project within the Congress was to advocate for a firm declared right to a fair trial by jury. The body, with help from Adams in bridging the gap between radicals and conservatives, agreed to endorse the Suffolk Resolves calling for boycotts of British goods until the Intolerable Acts were repealed.[19]

Revolutionary War[edit]

“”In my opinion Powder and Artillery are the most efficacious, Sure, and infallibly conciliatory Measures We can adopt.

|

| —Adams' rejection of the Olive Branch petition.[20] |

John's views on remaining with the British changed when the outbreak of hostilities began in 1775. He inspected militia troops and was dismayed to see how little supplies they had to fight a war and how poorly trained they were.[21] By this point, he considered an all-out independence war to be inevitable.

He help the Continental Congress nominated Washington to be Commander-in-chief of the American military out of a belief that the experienced and famous Washington would be the best possible rallying point for national unity.[22] Adams' writings from the time demonstrate that he was just about done with Britain's shit, and he opposed any attempts at conciliation. In fact, he soon became the most zealous promoter of American independence in the entire body, and he was frequently frustrated when others did not share his sentiment. Even those who agreed on independence still moved lethargically for the eager Adams.

Declaration of Independence[edit]

In May of 1776, Adams successfully proposed that the Congress declare its independence from the British Empire.[23] Congress then appointed a "Committee of Five", comprising John Adams alongside Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut, to draft an official declaration.[24] Only 33 years old, Jefferson actually wanted Adams to write it, but Adams refused on the very, very mistaken belief that the Declaration would not be remembered.[25] Jefferson's final document included some things Adams wasn't happy about, especially when it listed "horrors of the human slave trade" under George III's alleged crimes.[25] Adams, who was not a slave-owner, found it rich that Jefferson would criticize slave trade, despite being a slave-owner.

Still, Adams was widely noted as the fiercest defender of the document's adoption during debates.[26] Adams was thrilled when Congress chose to endorse the document and send it off to the British Crown.

Diplomatic service[edit]

After the Declaration, Adams spent most of the war as an American diplomat lobbying European powers for help against the British. In 1778, he arrived in France, where he was quickly overshadowed by the much more influential and popular Benjamin Franklin.[27] Shortly thereafter, Franklin sealed the deal on an alliance, and Adams was sent home having done nothing substantial. In fact, Congress didn't even give Adams a new job once he got back.

After burning some more bridges in France, he went to the Netherlands in the hopes of securing financial help from the rich little state that had also fought its way free from a colonial power. After tireless negotiation, the Netherlands recognized the US as a country, and John Adams' house in The Hague became the first-ever United States embassy.[28] Adams then managed to negotiate a $2 million loan and eventually got the Dutch to intervene against the British as well.[29] The loan proved to be the major thing, though, since America needed cash very urgently.

Alongside his rival Franklin and another delegate John Jay, Adams became part of the team that negotiated the end of the war against Britain. On behalf of his home state, he lobbied hard for concessions on fishing rights, which was a major source of income for the state at the time.[30] He also proved to be a keen diplomat in sensing the British desperation to end the war due to their financial troubles and the intervention of most of Europe's colonial powers against them. Adams, Franklin, and Jay all presented a firm united front that they wouldn't stand down in the war until and unless the British recognized American independence.[29] Their efforts resulted in the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the war.

Adams went to London to serve as the American diplomat tasked with ensuring that the peace stuck. In this post, he personally met King George III and ensured that their relationship would be cordial and respectful.[31] Unfortunately, in almost all other matters, his diplomacy was fruitless. Tensions after the treaty manifested immediately, like opening of British ports to American ships or to the removal of British troops from American soil, and Adams wasn't able to resolve these problems.[29] He spent five years in London, only leaving in 1788. While he had a nice time, he accomplished basically nothing.

Vice President[edit]

“”My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.

|

| —Adams complains to his wife.[32] |

Adams ran in the 1788 elections soon after returning home, and he managed to secure himself a spot as George Washington's vice president. As Adams would later complain, he needn't have bothered. The VP position was even less influential than it is today, with the VP only really being responsible for breaking ties in the US Senate. For a while, he took an active role in Senate activities by lobbying for his favored legislation, but complaints from the legislators threatened his popularity and deterred him.[33] Despite his frustration, Adams proved to be a loyal supporter of the Washington agenda, although most of this is attributed to the fact that both men tended to agree on political matters.

Washington rarely consulted his vice president. Since at the time the two offices featured men who ran separately, presidents and vice presidents rarely coordinated. His only real role in making policy was encouraging Washington to sign the Jay Treaty that helped normalize relations with the UK.[34] This made Adams deeply unpopular with the Jefferson faction, who wanted to support the French Revolution against the British.

Election of 1796[edit]

The election in 1796 was the first contended election in American history due to the retirement of George Washington after his second term. It was also one of the most contentious in American history due to the personal enmity between Jefferson and the Federalists. It featured mud-slinging attacks, like when Alexander Hamilton accused Jefferson of fucking his slaves and when Jefferson's team claimed that Adams wanted to be a king and nicknamed him "His Rotundity".[35]

The election also featured foreign interference from France, as minister Pierre-Auguste Adet acted on orders from his government to spread threats and dig up secrets in an attempt to get the pro-French Jefferson elected.[36] Adams' own camp also split when Hamilton turned against him and Adams called him out as a womanizer and a "Creole bastard".[37]

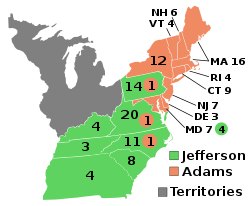

In the end, Adams won the presidency by a narrow margin, receiving 71 electoral votes to 68 for Jefferson.[38] He needed 70 to win, making this election a real nail-biter. The election also revealed a major political truth: that the North and the South had very different political objectives. As stipulated by the Constitution at that time, Jefferson as the runner-up became the vice president, setting the stage for much frustration and hostility between the two men.[39]

Presidency[edit]

Relations with Hamilton[edit]

Alexander Hamilton still had a lot of loyalists in the Adams administration since Adams felt it prudent to retain most of Washington's cabinet and civil service appointees. Jefferson quickly judged them as being only slightly less hostile to Adams than was Jefferson himself.[40] Indeed, Hamilton's loyalists worked hard to undermine Adams at every point and feed political information to Hamilton to be used in public attacks.[41] Hamilton also ended up writing a long letter detailing all of the reasons why Adams should not be elected to a second term, a letter which may well have helped cost Adams re-election.[42] All this in spite of Adams choosing to maintain Hamilton's supported fiscal policies. Hamilton was a bit of a dick.

Quasi-War with France[edit]

Like his predecessor Washington, John Adams was adamant about keeping the US distanced from the French Revolution. The French revolutionaries saw this as an insult and a betrayal considering that France had bailed out America in the American Revolution. The French were enraged further when the US started refusing to pay its debts, since the US was in a financial clusterfuck and France's government was totally different anyways. French privateers started attacking American ships to make up the cash. Matters came to a head in 1797 with the "XYZ Affair", in which American diplomats in Paris were intercepted by the French Foreign Minister's intermediaries and ordered to pay reparations and bribes before being allowed to see the Foreign Minister.[43] Already outraged, the American diplomats departed France altogether after the Foreign Minister informed them that he would not cease attacks on American shipping.

Adams responded by putting a rush order on the remaining frigates that had been commissioned by Washington and sending them into the Atlantic to protect American ships.[44] This began the period of time known as the "Quasi-War", where US and French ships battled across the ocean despite not being officially at war. The US Navy actually performed much better than expected in this conflict by targeting French ships near their Caribbean colonies. The USS Constellation won two major engagements by capturing the French ship L'Insurgente and then heavily damaging the La Vengeance.[44] Adams' war also served to help the rebelling slaves of Haiti by lifting the French blockade against them, which did even more to anger the Jeffersonian Southerner faction.

In the end, Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in France and decided that the war was a waste of time. He negotiated the Convention of 1800 to guarantee free trade between both nations while amicably dissolving their old alliance.[45]

Alien and Sedition Acts[edit]

Adams is most infamous for signing four pieces of deeply troubling legislation. They made it harder for an immigrant to become a citizen (Naturalization Act), allowed the president to imprison and deport non-citizens who were deemed dangerous (An Act Concerning Aliens) or who were from a hostile nation (Alien Enemy Act of 1798), and criminalized making false statements that were critical of the federal government (Sedition Act of 1798).[46] These pieces of legislation were forced through Congress by members of Adams' Federalist Party, who believed that the measures were necessary in a time of war against France.

The Sedition Act was the most infamous law of the four, since it made it a crime to publish "false, scandalous, and malicious writing" about government officials, punishable by outrageously steep fines and/or up to 2 years in jail. This act led to the arrest of John Daly Burk, a fiercely patriotic newspaper editor and writer who antagonized Adams by writing a play he didn't like and saying Adams wanted to be king. Burk only escaped the charge by promising to leave the US (he moved to upstate Pennsylvania instead).[47][48][49] Congressman Matthew Lyon of Vermont was also sentenced to four months in jail under the Sedition Act.[50] First Amendment? What's that?

Luckily, the war threat eventually passed, and the Democratic-Republicans won control of the federal government in 1800, meaning that these pieces of legislation were either repealed or allowed to expire.[51] The only one that remained was the Alien Enemy Act, which proved to be a major part of Woodrow Wilson's crackdown on civil liberties during World War I.

Social Issues[edit]

With the modern debate over healthcare laws still going on, Adams' socialism socialized health care law has been brought up as a precedent for Barack Obama's reforms. In 1798, Adams signed the Act for the Relief of Sick and Disabled Seamen. Essentially, it set up a socialism socialized health care system for US sailors with publicly run hospitals and vouchers for private insurance. This was funded by a mandatory tax.[52]

Considering that many members of Congress had actually helped draft the Constitution, they didn't really feel the need to debate the law's constitutionality to any great extent.[53]

Adams also oversaw other important achievements, including the appointment of William Henry Harrison as Governor of the new Indiana Territory and Ben Stoddert as the new Navy Secretary, suppressed the Fries’ Rebellion, protected American defenses by building up a Navy, signed a law to stop unauthorized responses from other nations, signed another bill to protect shipping rights, signed a law to help develop the Library of Congress, and appointed John Marshall as the Supreme Court Justice before leaving office after being defeated by Jefferson in the 1800 Election.

Failed reelection[edit]

Adams was one of relatively few US presidents who failed to win re-election despite having the incumbency advantage. In spite of his achievements, he ended up in an uphill battle cocking up some stuff for himself, like signing the disastrously unpopular Alien and Sedition Acts, failing to compromise with the Federalists, and alienating much of his own party by abruptly firing Hamilton loyalists in his cabinet.[39]

Once again, the campaign devolved into mud-slinging bullshit. His team denounced Jefferson as an atheist and a "Jacobin", trying to tie him to the worst excesses of the French Revolution.[39] The Democratic-Republicans in turn called Adams a monarchist and an enemy of the United States' republican values. At one point, they accused Adams of plotting to have his son marry one of the daughters of King George III and thus establish a dynasty to unite Britain and the United States.[39] The Federalists retaliated with a bizarre narrative about how Jefferson supposedly vivisected people in hideous experiments beneath his Monticello mansion. The Federalists were also badly divided, most notably by the above noted sabotage from Alexander Hamilton.

Ultimately, Jefferson unseated Adams by flipping New York and Maryland to receive 73 votes to Adams' 65.[54] Adams' narrow victory had become a decidedly less narrow defeat.

Misquoting by the religious right[edit]

Adams, being one of the most religious of the founding fathers, has been subject to several misquotes regarding how the government of the United States is supposed to operate. One frequent quote of his used to back up the idea that the United States is supposed to be a Christian nation is his 1798 statement that "Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other."[55] Joshua Charles, in a 2017 video for PragerU, used the quote as evidence the United States was not founded to be secular.[56]

First off, this notion gets what Adams thought of the Constitution totally backwards. Thaddeus Russell documents in A Renegade History of the United States how the more conservative founders were actually upset with British rule primarily because it failed to create "a moral and religious People," and assumed the responsibilities of self government would create such a civilization. Saying it imposes Christianity on that basis is a total misunderstanding of the cause and effect Adams thought would exist.

For the record, Adams never did anything to force his religious beliefs onto others, even saying "I hope that Congress will never meddle with religion further than to say their own prayers."[57]:15

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Quotes about John Adams. Wikiquote.

- ↑ The portable John Adams. New York : Penguin Books, 2004.

- ↑ Levy, Leonard (1995). Seasoned Judgments: The American Constitution, Rights, and History. p. 307. ISBN 9781412833820.

- ↑ How Every President Died YouTube

- ↑ John Adams Quotes. John Adams Historical Society.

- ↑ Biography of John Adams: Lawyer (1758-1761). University of Groningen.

- ↑ June Highlight: The Adams Family. Harvard University. "Declaration Resources Blog."

- ↑ John Adams. Trial Lawyer Hall of Fame.

- ↑ Legal work from 1762 to 1767. John Adams Historical Society.

- ↑ After the Stamp Act. John Adams Historical Society.

- ↑ Legal Papers of John Adams, volume 2. Massachusetts Historical Society.

- ↑ Diary Entry of John Adams Concerning His Involvement in the Boston Massacre Trials. Famous Trials.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Boston Massacre.

- ↑ Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, 1770. Gilder Lehrman Institute.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials. Constitutional Rights Foundation.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 The Boston Massacre Trials. John Adams Historical Society.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Intolerable Acts.

- ↑ Ferling, John E. (1992). John Adams: A Life. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-08704-9730-8. p. 128–130

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Suffolk Resolves.

- ↑ From John Adams to Moses Gill, 10 June 1775. National Archives.

- ↑ Smith, Page (1962a). John Adams. Volume I, 1735–1784. New York, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc. OCLC 852986601. p. 196

- ↑ George Washington: The Commander In Chief. UShistory.org

- ↑ Signers of the Declaration of Independence: John Adams. UShistory.org.

- ↑ Drafting the Declaration of Independence. Constitution Facts.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 The Declaration of Independence. PBS.

- ↑ Morse, John Torey (1884). John Adams. Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. OCLC 926779205. p. 127–128

- ↑ John Adams: Diplomat to France. Boston Tea Party Museum.

- ↑ John Adams Was the United States’ First Ambassador as Well as Its Second President. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 John Adams' Diplomatic Missions. PBS.

- ↑ Treaty of Paris 1783. John Adams Historical Society.

- ↑ John Adams meets George III. The Crown Chronicles.

- ↑ John Adams. The White House.

- ↑ John Adams, 1st Vice President (1789-1797. US Senate.

- ↑ McCullough, David (2001). John Adams. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-14165-7588-7. p. 456–457.

- ↑ On This Day: The first bitter, contested presidential election takes place. Constitution Center.

- ↑ Foreign Election Interference in the Founding Era. Lawfare.

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-11012-0085-8. p. 522

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on 1796 United States presidential election.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 John Adams Campaigns and Elections. Miller Center.

- ↑ Ferling, John E. (1992). John Adams: A Life. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-08704-9730-8. p. 333

- ↑ On John Adams in “Hamilton”. Medium.

- ↑ John Adams. Hamilton's Final Act.

- ↑ The XYZ Affair: A Dispute Between France and the U.S. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 The Quasi-War. American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Convention of 1800.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Alien and Sedition Acts.

- ↑ Felled on the Field of Honor: The Seditious Patriot: Mr. John Daly Burk, Jack Lynch, Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Autumn 2005

- ↑ To Thomas Jefferson from John Daly Burk, John Daly Burk, before 19 June 1801, reproduced at Founders Online, US National Archives

- ↑ Sorry America, history proves Donald Trump is not the first US president with totalitarian impulses, Quartz, Feb 13, 2017

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Matthew Lyon.

- ↑ Alien and Sedition Acts. Britannica.

- ↑ Congress Passes Socialized Medicine and Mandates Health Insurance -In 1798. Forbes.

- ↑ John Adams and the Affordable Care Act. The American Prospect.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on 1800 United States presidential election.

- ↑ From John Adams to Massachusetts Militia, 11 October 1798

- ↑ Was America Founded to Be Secular?

- ↑ They'd Rather Be Right by Edward Cain