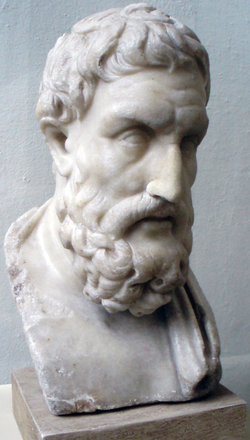

Epicurus

| Thinking hardly or hardly thinking? Philosophy |

| Major trains of thought |

| The good, the bad, and the brain fart |

| Come to think of it |

“”Thus Natural Philosophy supplies courage to face the fear of death; resolution to resist the terrors of religion; peace of mind, for it removes all ignorance of the mysteries of nature; self-control, for it explains the nature of the desires and distinguishes their different kinds; and [...] the Canon or Criterion of Knowledge, which Epicurus also established, gives a method of discerning truth from falsehood.

| ||

| —Lucius Torquatus, in Cicero's De Finibus, Book I, Chapter XIX[1] |

Epicurus was an ancient Greek philosopher living in the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE during the Hellenistic period of Greek philosophy. Mildly popular in his own time, he is now best remembered for his teachings regarding the soul and ethics and Epicureanism, his own brand of philosophical thought. He was innovative in that he allowed slaves and women to become members of his philosophical group. Notable contemporaries of his time include Zeno, founder of the Stoic school of thought; Antisthenes, founder of the Cynic school of thought; and Plotinus, founder of the neoplatonistic school of thought.

Physics[edit]

Epicurus was an early proponent of naturalistic philosophy. He was a materialist, and argued that the universe was made of atoms in various arrangements. He did this based on an empirical epistemology. He believed that our senses (including our sensations of pleasure and pain) are how we determine truths about the world.

As a result of his materialist views, Epicurus taught that the soul died with the body. He also argued that the gods must be made of atoms, and that because of this, the gods cannot be the creators of the universe (since they are not above nature). The Epicurean deities were understood as immortal aliens living a blissfully disinterested existence, akin to a deist god. For example, if a shepherd was struck by lightning, it was not because Zeus was displeased with the shepherd; it was because Zeus got hammered and the shepherd was unlucky. As a result, he felt that praying or sacrificing to them was pointless, though they should still be worshiped as ideal beings.

Epicureanism[edit]

Epicurus taught an early form of secular ethics known as consequentialism. He believed that pleasure and pain are the only things that have intrinsic value to beings, and that the goal of life was to maximise pleasure and minimise pain for both yourself and others. He taught that people thus needed four virtues: prudence, justice, friendliness and fortitude. Epicurus emphasised that the pleasure from an action must be weighed against the negative side effects, a concept that is called the 'hedonic calculus'. For example, you could save up £1000, buy twenty kilograms of chocolate, and eat it all at the same time. In this case though, you need to weigh the pleasure of eating chocolate against the inevitable stomach ache and the weight you'll gain from eating a third of your body weight in chocolate. Epicurus had a second part of the hedonic calculus that he said to consider: is it worth the momentary benefit of £1000 of chocolate or buying a new bike a bit later for £1100? The greater pleasure, even if it causes a slight negative effect at the moment, is the greater good. Epicurus also taught that sensual pleasures weren't all that there was to the world. Epicurus noted that appreciation of art and friendship also count as pleasure. Moreover, Epicurus taught that the enjoyment of life also required old Greek ideals of self-control, temperance, and serenity. Desires need to be curbed, and serenity will help us to endure the pain we may face.[2] Epicurus also preached altruism over self-interest, saying that friendship "dances around the world, calling all people to a life of happiness." He taught that the best life for the individual is one that is lived with other people for their benefit in addition to the individual's own benefit.

Epicurus also taught that death need not be feared, as no one has ever been bothered by being dead. He would later go on to make the elegant statement:

“”Death does not concern us because as long as we exist, death is not here. And when it does come, we no longer exist.

|

| —Epicurus |

Epicurus' view on justice was that it was a social contract, created for mutual benefit. What is just, in this view, is what people would agree to if they were rational and not under threat of force.[3]

Epicurean philosophy became one of the most influential philosophies of Rome. Some of its followers included Julius Caesar and Cassius.[note 1] Epicurean Epitaphs are found all over the Roman world, saying: "I was not. I have been. I am not. I do not mind."

Despite his contributions to philosophy, he was not looked upon kindly by the Church Fathers and later Medieval writers due to his view that all things were made up of matter and the soul died with the body.[note 2] Conversely, he was cited positively by later atheist, hedonist and materialist thinkers.

See also[edit]

- Lucretius, who wrote down much of Epicurus' philosophy

External links[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Caesar argued against the death penalty based on Epicurean arguments. Since death didn't harm a person, it wasn't an appropriate punishment.

- ↑ He is in the sixth circle of Dante's Hell, the circle of heretics (along with his followers), while Plato and Aristotle occupy the comparatively peaceful Limbo. "Apikiron" has become the Hebrew for heretic as well.

References[edit]

- ↑ Rackham, Horace, ed. (1924). Cicero: De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 68-69.

- ↑ Gaarder, Jostein. "Hellenism." Trans. Paulette Møller. Sophie's World. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2007. 131-32. Print.

- ↑ Epicurus on Justice, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.