There is no RationalWiki without you. We are a small non-profit with no staff—we are hundreds of volunteers who document pseudoscience and crankery around the world every day. We will never allow ads because we must remain independent. We cannot rely on big donors with corresponding big agendas. We are not the largest website around, but we believe we play an important role in defending truth and objectivity. |

Fighting pseudoscience isn't free. We are 100% user-supported! Help and donate $5, $10, $20 or whatever you can today with |

Greece

“”Conquered Greece took captive her savage conqueror and brought her arts into rustic Latium.

|

| —Quintus Horatius Flaccus, a Roman poet during the reign of Caesar Augustus, describing the influx of Greek culture into the ruling Roman Empire.[1] |

“”From now on I will call our esteemed EU partner "the former Ottoman possession of Greece (FOPOG)."

|

| —David Cameron in a jab at Greece over the North Macedonia name dispute in 2003.[2] |

Greece (Greek: Ελλάδα, Ellada), officially the Hellenic Republic (Ελληνική Δημοκρατία, Ellinikí Dimokratía), is a country in south-eastern Europe consisting of a mountainous peninsular landscape jutting out of the southern Balkans along with a multitude of islands scattered across the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean. It's notable for its extremely long ancient history, and has a reputation as the cradle of Western civilization due to Ancient Greece's heavy influence on philosophy, culture, and the Roman Empire. Sadly, Greece's glory-days seem to be over for the time being, as the country in the modern era is known more for its 30-year squabble over North Macedonia's name,[3] diplomatic slap-fights with Turkey over maritime borders,[4] and a catastrophic decade-long economic meltdown[5] far more than anything worthy of a grand paragon of Western civilization. About 90% of the current Greek population are Eastern Orthodox Christians, while 2% are Muslim and 4% are unaffiliated.[6] Greece is a democratic parliamentary republic with its capital in Athens.

The territories of the ancient Greeks fostered the first advanced civilizations in Europe, although (or because) those Greeks (Hellenes, as they called themselves) grouped themselves into many infighting city-states. During this time, Greeks established colonies across Mediterranean Europe from present-day Spain to present-day Ukraine, began Western literature and Western philosophy, and made great leaps forward in science and mathematics. On the negative side, Ancient Greece tended to be warlike and reliant on slavery. The experience of constant warfare helped the Greeks fight off the much larger Empire of Persia in 492 and 480 BCE, but it also led to a catastrophic war between the city-states of Athens and Sparta in 431 BCE. With many of the cities having smashed each other into oblivion, the northern semi-Greek state of Macedon ascended to unite most of the Greek lands with relatively little resistance and then went on to conquer a massive empire under its famed leader Alexander the Great. Like many great conquerors, Alexander cast his new empire into chaos by dying without a succession-plan, and the Roman Republic began to intrude into Greek affairs by 200 BCE. By 27 BCE, all of Greece was annexed into the Roman Empire. However, the Romans quickly became enamored with Greek culture and philosophy, with Greek ways becoming a cornerstone of the empire.

During the rise of Christianity, Greeks and Greek-speakers like Saint Paul became vital figures in the religion's early history. When the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 CE, the Greeks continued as the Eastern Roman Empire, known then as the "Kingdom of the Romans" and known now as the "Byzantine Empire". Its religious leaders shaped Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Unfortunately for them, the empire started to come under constant assault from Muslims to the east and from European Crusaders from the west. Islamicised Turks moved in from farther east, conquering Greek lands, capturing the then capital city (Constantinople) in 1453, and establishing the Ottoman Empire as successor to the Byzantines.

Under Turkish domination, the Greek people faced heavy oppression, leading to repeated and bloody uprisings. This culminated in a brutal war of independence in 1821, which the Greeks won with significant European assistance. The price of independence was the imposition of a German monarch over Greece - he ruled as a despot until a revolution swept him from power in 1862. Greek history was further defined by its hostility towards the Turks, as significant tracts of Greek land remained under Ottoman rule. This led Greece into several wars against the Ottomans, most notably Greece's involvement in World War I. The latter war was a disaster for the Greek people, as the Ottomans conducted a horrific genocide against their Greek population[7] and fought a total war that left Greece in ruins.

Political instability plagued Greece, leading to politician Ioannis Metaxas seizing power as an authoritarian strongman dictator in 1936 with assistance from the Greek king. He led Greece during World War II, in which the country was brutally invaded by fascist Italy. Greece tenaciously resisted the invasion, but succumbed to German invasion in 1941. After the war, Greece descended almost immediately into civil war between the dictatorship government and communist rebels. The civil war caused even more economic destruction and population displacement. More political instability followed, and the dictatorship era finally ended in 1974.

After the end of the dictatorship, the quality of life in Greece improved greatly. Tragically, this trend ended abruptly in the 2009 financial crisis and the subsequent austerity policies, which wrecked the Greek economy again. The country has yet to fully recover from this. Financial woes accompanied a refugee crisis from the Middle East, fueling a right-wing resurgence, causing social strife, and straining the Greek economy even more.

The Greek language uses an alphabet that gave the world π (The Greek and Cyrillic alphabets seem to be the only ones using a capital Π, which sadly gets ignored by users of other writing systems. It does, however, find use in mathematics, where capital pi notation, similar to the sigma notation used for series of summation, is used to simplify the presentation of the product of a sequence of values).

Greeks find it amusing to see their 'whiteness' change based on the conversation. When it's discussing their supposed "Western Culture" past, they're glorious Aryans. (Or maybe they think Greek people all look like marble busts.) When discussing the debt crisis, they're swarthy sea-people on welfare with no culture.

History[edit]

Ancient Greece[edit]

Early civilization[edit]

Greece was the cradle of the first advanced civilizations in Europe, thus considered the birthplace of Western civilization.[8] Greek culture was heavily influenced by its natural environment. With impassable mountains covering much of the landscape and few natural resources easily accessible, the Greek people were forced to become a maritime civilization to survive and grow.[9] Instead of focusing on agriculture like many other early civilizations, the Greeks colonized islands across the Aegean and traded with other cultures in the ancient world. As the Greek people spread out across the seas, their homeland's waters and rugged mountains kept them separate, ensuring that no unified ancient Greek state could exist.[9]

The Minoan people, established on the island of Crete, became the first Greek people to use their trade wealth to develop a true civilization in around 3000 BCE.[10] Their later decline, around 1450 BCE, is mysterious due to its unknown cause and high level of destruction, becoming the subject of wild speculation.

Later came the Mycenaean civilization from mainland Greece, which focused less on the arts and culture and more on being austere and warlike.[11] Mycenae became the model for most Ancient Greek city-states, with its pantheon becoming the Greek pantheon and its warlike ways becoming the norm for Greek polities.[9] Unfortunately, historians don't know much about Mycenae since the civilization was destroyed by similarly mysterious circumstances sometime around 1100 BCE. The downfall of Mycenae ushered in the Greek Dark Age.

Greek Dark Age[edit]

The collapse of Greece's primary ancient civilization resulted in a near-complete loss of literacy, and Greek settlements established during this time were small and scattered.[12] While Mycenaean culture persisted, it only did so through tradition, ritual, and word of mouth. This political fragmentation also caused even more wars between Greeks squabbling over what was left behind.

That being said, scholars today find the term "Dark Age" to be something of an overly loaded term. While Greek civilization went into the toilet for a while, some major developments occurred during the era. Ironworking began in response to the increased number and ferocity of Greek wars.[12] Iron kill good, better than bronze! By 800 BCE, Greeks started to build more advanced settlements again, and the Greeks also recovered their literacy by adopting a new alphabet.[12] Specifically, the Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet (from modern-day Lebanon) and used it to create a phonetic representation of their language.[13]

Any non-idiot historian can tell you that literacy is essential to forming any complex civilization. After, and only after, the reestablishment of a Greek written language could Greek civilization resume.

Archaic period[edit]

The Archaic period was shaped by the rising population of Greece and its increasing contacts with the rest of the world, which led the Greeks to begin colonizing farther and farther away.[14] It was also the beginning of the great age of Greek philosophy and politics.

Athens was probably the most important city-state during this era, making the first great leap forward in Greek philosophy and politics. Athens' government was dominated by wealthy aristocrats (of course) who gradually seized more and more wealth and power from everyone else to the point where most common people became debt slaves.[15] This, naturally, wasn't too great for social stability and cohesion, so the Athenian ruling class decided to attempt to fix the situation through laws. The first lawgiver was Draco in 621 BCE (who gives us the term "draconian"), and his laws were immediately hated since they imposed the death penalty for just about every infraction.[15] Damn.

Since that didn't work out, the Athenians then turned to Solon in 594 BCE, and he dramatically restructured Athenian society into a stratified yet mostly fairer class structure.[16] He also introduced the concept of equality before the law. The Athenian system then gradually evolved into the first real democracy, where male citizens (not women, enslaved people, foreign residents, or "useless" people) had the right to freely participate in government.[17] Athenian democracy was not without its flaws, of course. Only 10-20% of the population were citizens, and only a fraction of that number, maybe 100 of the wealthiest people, had the greatest power to shape political agendas.[17] Athenian citizens could also make some pretty bad decisions, like executing generals despite winning battles or ordering the execution of Socrates.

It was, however, better than the Spartan system.

Sparta (also known as "THIS IS SPARTAAA!!!"), located farther south, was an absolute nightmare. It became the second great city-state of Greece through its military prowess, achieved through brutally training male citizens from the age of seven in a series of tests meant to develop pain tolerance, endurance, and warfare skills.[18] Boys would be deprived of shoes and good clothing, only given minimal food and instead encouraged to fight each other for extra portions, and ruthlessly beaten for any infractions (not for doing it but for getting caught).[18] On the upside, Spartan male citizens had the right to participate in government once trained, and Spartan female citizens enjoyed much, much greater freedoms than women elsewhere in Ancient Greece.[19]

Much worse was the plight of enslaved people (known as "helots"), who made up almost the entire population of Sparta and were subjected to ritual mass murder by the trained citizens to keep the helots terrorized and teach the citizens how to kill.[20] As you would expect, there were slave revolts, but Sparta proved highly adept at putting them down. The life of a helot was one of constant forced labor and bloody terror.

One last thing to note was the Olympic games began in 776 BCE and featured contestants from the Hellenic world.[14] The Spartans tended to do really well in them.

Persian and Peloponnesian wars[edit]

“”Go tell the Spartans, you who read:

We took their orders, and lie here dead. |

| —Simonides, epitaph for the dead of Thermopylae.[21] |

The Archaic period ended with the Persian wars when the Greek city-states (notably the great rivals of Athens and Sparta) united to fend off a great invasion from the massive Persian Empire in 490 and 490 BCE. With Spartan land warfare prowess, Athenian sea power, and the rugged landscape of Greece, the Greeks could preserve their independence against a much more numerous foe.[22] This war featured the famous Battle of Thermopylae![]() , in which about 7,000 Spartans and allied Greeks led by Spartan King Leonidas I managed to delay an army of around 70,000 Persians for three days. The battle was made famous by its depictions in pop culture, most recently in the 2007 film 300.[23]

, in which about 7,000 Spartans and allied Greeks led by Spartan King Leonidas I managed to delay an army of around 70,000 Persians for three days. The battle was made famous by its depictions in pop culture, most recently in the 2007 film 300.[23]

The Persian Wars left Sparta and Athens the absolute great powers of Greece. Unfortunately, two naturally opposed great powers can't live in peace for too long, and what began as a cold war turned into a hot one. The Peloponnesian War began in 432 BCE, and it quickly became one of the most sickeningly brutal wars in Greek history, with entire city-states being exterminated and previously unthinkable atrocities being committed upon non-combatants.[24] The war's scope was also much larger than Greece had seen before, with Athens deploying a military and political alliance called the Delian League and Sparta, in turn, fighting at the head of the Peloponnesian League.

Sparta ultimately won the war, making it the effective ruler of Greece. This wasn't to last very long, and the period became a textbook example of what happens when you focus more on conquering than ruling. The Spartan citizens were unsuited to rule since they were trained in warfare and almost nothing else. Sparta also overextended itself by waging even more wars to expand its territory, allowing its old enemies of Athens and some of its disgruntled allies to overthrow them.[24]

Classical period[edit]

“”Athens, the eye of Greece, mother of arts

And eloquence. |

| —John Milton, Paradise Regained.[25] |

After Sparta's downfall came Ancient Greece's golden era, the time that really encapsulated the popular concept of "Ancient Greece." First, Athens and then Thebes became the new hegemons of the Greek world, and Greek thinkers began making great steps forward in philosophy and science. Rationalism became the new approach for many philosophers in approaching the world's workings, with Athenian philosopher Plato and his student Aristotle coming to define Western thought.[26] Among the most famous Greek mathematicians from this time are Euclid![]() , the founder of modern geometry, and Archimedes

, the founder of modern geometry, and Archimedes![]() , who became one of the greatest scientists and mathematicians of all time. Also notable was Eratosthenes, who, in 240 BCE, used mathematics to prove that the planet is a sphere and (astonishingly accurately) calculated its circumference.[27] Basically, fuck you, Flat Earthers; even people from 2,000 years ago knew you were full of shit.

, who became one of the greatest scientists and mathematicians of all time. Also notable was Eratosthenes, who, in 240 BCE, used mathematics to prove that the planet is a sphere and (astonishingly accurately) calculated its circumference.[27] Basically, fuck you, Flat Earthers; even people from 2,000 years ago knew you were full of shit.

This shift towards rationalism reflected itself in Greek art, with depictions of humans becoming far more detailed and realistic.[26] It also resulted in the founding of the modern school of history, as Greek writer Herodotus![]() was the first person recorded as having approached past events with an analytical perspective. He actually coined the term "history". That being said, his Histories, which attempted to chronicle the Persian Wars, were very subjectively written to the point of being propaganda and rather stupidly trace the conflict's origins back to the semi-mythical Trojan War while taking the acts of the Greek gods for granted.[28] That's why other historians point to a different Greek writer, Thucydides, as the first true historian, since he was the first historian who applied standards of impartiality when evaluating historical evidence and didn't chalk shit up to "the gods diddit".[29]

was the first person recorded as having approached past events with an analytical perspective. He actually coined the term "history". That being said, his Histories, which attempted to chronicle the Persian Wars, were very subjectively written to the point of being propaganda and rather stupidly trace the conflict's origins back to the semi-mythical Trojan War while taking the acts of the Greek gods for granted.[28] That's why other historians point to a different Greek writer, Thucydides, as the first true historian, since he was the first historian who applied standards of impartiality when evaluating historical evidence and didn't chalk shit up to "the gods diddit".[29]

This was also the golden era of Athens after the statesman and politician Pericles had made democracy a permanent fixture of the city-state's politics and initiated the building of the Athenian Parthenon.[30] Athens' ascent made Classical Greece possible since it sponsored and funded the arts and philosophy.

Macedonia and Alexander the Great[edit]

“”What is the purpose of adventuring around the world? A king must be an administrator.... Alexander was a man full of great sound, lighting, and thunderbolt; [he was] like a cloud in spring or summer, which passed over the kings of the earth, rained upon them, and disappeared.

|

| —Abu'l-Fazl Bayhaqi, 11th century Persian historian.[31] |

Athens' time in the sun was cut short by the lasting damage caused by the Peloponnesian War and its clashes with the city-state of Thebes. With Athens and Sparta both on the outs, a power vacuum opened up, just waiting for an ambitious Greek city-state to fill it. In came Philip II of Macedon, who took control of a backward monarchy in northern Greece in 359 BCE and began to whip it into shape by training its armies and modernizing its administration.[32] He then challenged Athens and Thebes and defeated their alliance in the pivotal Battle of Chaeronea, leaving Macedon as the unquestioned ruler of the Greek states.[33] Without Philip II, his son would not have had the chance to become world famous.

His son, by the way, was Alexander III, better known as "Alexander the Great." He took the throne in 336 BCE and quickly started to attack Persia to "liberate" the Greek population of Anatolia, who remained under the empire's rule.[34] He solidified his rule by proclaiming himself the demigod son of Zeus, thus claiming divine and heroic ancestry.[34] While those claims should, of course, be treated with skepticism, Alexander did manage to lead his armies to victory over a much larger Persian force at the Battle of Issus in 333 BCE.[35] This victory, achieved while Persian emperor Darius III was on the field, effectively destroyed the Persian Empire. Combined with Alexander's conquests in Egypt and the Levant, the seizure of Persia turned Macedonia into the world's largest empire up to that point.

Although his abrupt appearance into the pages of history was followed by an abrupt disappearance, Alexander did have a pivotal impact on the progress of Western civilization. Greek culture influenced most of Europe and beyond, with Greek people intermarrying and integrating into cultures around the ancient world.[34] This led to the Hellenistic Period, in which Greek thought and culture became nearly universal in many areas.

Wars of the Diadochi[edit]

“”[Alexander's] genius was such that he ended an epoch and began another — but one of unceasing war and misery, from which exhaustion produced an approach to order after two generations and peace at last under the Roman Empire.

|

| —Ernst Badian, Austrian historian at Harvard University, 1964.[36] |

After establishing this new Greek empire, Alexander abruptly died in 323 BCE from mysterious causes, leaving the empire without a leader. Alexander had no adult children and had allegedly wished his empire to be inherited by "the strongest", a foolish idea that led his empire to be divided among three of his generals.[34] They were called the "Diadochi", or successors. Complicating the matter was that Alexander had a young son with his wife Roxanne of Bactria, but they were soon assassinated, resolving the threat of a peaceful inheritance.[37]

Greece itself was taken by Antigonus, but he faced the even stronger realms formed by the other two Diadochi. Ptolemy took all of Egypt and part of Anatolia, while Seleucus lucked out by taking all of Persia plus Mesopotamia plus a big chunk of Anatolia.[34] Each hoped to reunite Alexander's empire by defeating the others, and this naturally led to decades of war between 322 and 281 BCE.[38]

The continental royal rumble caused decades of bloodshed and chaos in the name of personal ambition which shook the landscape of Greek geopolitics. City-states proved too weak to defend themselves effectively against the larger and more centralized monarchies and empires, and democratic ideals were discredited in favor of absolute authority.[39] Bactria, one of the farthest east of Alexander's successor kingdoms (located around what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan), would lead to cultural exchanges with both the nearby Indian kingdoms and even the Han Empire in China.[40]

Even after the end of the Diadochi Greek-on-Greek violence, polities in Greece continued to war on each other, perpetually weakening themselves in the face of growing outside threats. Not smart.

Roman rule[edit]

Conquest of the conquerors[edit]

While the Greeks were busy killing each other, a new power rose to the west. The Roman Republic used took advantage by building a power base and expanding its territory. In 168 BCE, Rome proved its power by smashing the armies of Antigonid Macedonia at the Battle of Pydna, ending Alexander's realm and establishing itself as the dominant power in the Greek world.[41] Rome had done this at the request of some of Macedonia's Greek foes, and those remaining Greek states became clients of Rome paying for the privilege of Rome's military protection.[42] They eventually realized that Rome wasn't quite the benevolent protector it pretended to be, and two Greek revolts against Roman rule resulted in Greece being completely annexed in 27 BCE.[43]

Romans initially considered the Greeks to be barbaric and warlike, but over time Roman educated elites discovered Greek works on philosophy and the arts. Publius Vergilius Maro, known as Virgil, became one of Rome's greatest writers and was directly inspired by the epic works of Homer, such as the Illiad and the Odyssey.[44] Greek science and philosophy, coupled with Virgil's depictions of Greek figures in his works, caused Greek culture to become tremendously influential in Rome. The Roman pantheon, which had developed independently of Greece, was quickly revised to fit with Greek stories and mythology, leading to a point where Greek and Roman gods were essentially indistinguishable.[45] This happened in some different ways. The Roman goddess Venus, for instance, was associated with the Greek goddess Aphrodite despite the Roman goddess being dignified and motherly and the Greek one being an irresponsible sex maniac.[45] The Roman god Janus of doorways and transitions remained largely unchanged, while Apollo and Hades were taken wholesale into the Roman pantheon under Latinized names.[45] The Romans had done this before, as they also revered the mother goddess Cybele from the Phrygian pantheon and the goddess Isis from Egypt.[45]

Although Greece had to suffer the indignity of foreign rule, it did benefit greatly from the Pax Romana, which was the longest period of peace in Greece's long history up to that point.[43] Greek cities experienced a prolonged era of prosperity and cultural development, and urban Greek elites became part of the Roman Empire's ruling class with full rights in the Senate.[46] Greek became one of the official languages of the Roman Empire.

Early Christianity[edit]

Greece and the Greek people played an essential role in shaping the rise of Christianity within the Roman Empire. The religion's spread was slow, and Roman authorities initially considered it another of the empire's mystery cults.[47] However, Christians distinguished themselves by refusing to honor the Roman state-mandated gods and were thus treated with suspicion and sometimes hostility by Roman authorities.[48] For the Romans in power, religion was less about faith and more about power and cold, hard cash.

Hellenized and Greek communities in the eastern empire were incredibly influential in cradling Christianity. The religion's early leaders and writers were Greek speakers, although often not themselves Greek.[49] Paul of Tarsus, a Greek-speaking converted Jew, played an instrumental role in establishing Christian communities throughout the east.[50]

Christianity was eventually legalized outright by Roman emperor Constantine in 313 CE due to the rising political influence of the Christians.[51] That was nice, but it unfortunately only caused more problems. Christians became much more vocal and powerful, and they used their new freedom to start turning on each other over specific religious doctrine issues, leading to major riots in the empire.[48] Oh shit.

Constantine decided to solve the problem by holding the First Council of Nicaea in 325 in the Greek Anatolian city of the same name among various Christian clergy. The council set the tone for much of the succeeding Christian-oriented religions by settling disputed issues and issuing decrees outlining the proper method of consecrating bishops, condemning lending money at interest by clerics, and confirming Alexandria and Jerusalem as seats of high patriarchs.[52] Most notably, though, it declared the first official heresy by denouncing Arianism, or the idea that Jesus Christ was created by God rather than being God.[53] This played into the promulgation of the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, which forms the general outline of Christianity for all major branches to this day.[54] Ever since, Christianity has held the official position that Jesus is somehow the Son of God while also being God at the same time.

Ultimately, Nicaea did not unify Christianity. Instead, it quite decisively fractured it for a long time. In 380 CE, Emperor Theodosius I promulgated the Edict of Thessalonica, effectively declaring Nicene Christianity as the Roman Empire's official faith.[55] The emperor then kicked off a wave of persecution directed towards the Arians, who he viewed as intolerably heretical. Again, this wasn't over differences of religion but over petty doctrinal disputes. Along with the stubbornly existing Arians, there were other significant heretical schools of thought in Christianity. These included Pelagianism (which denied original sin) and Macedonianism (which denied the divinity of the Holy Spirit).[56]

While establishing Christianity as the Roman Empire's new religion, the emperor Constantine decided to construct a new capital in the Greek city of Byzantium, which occupied the European half of the Bosporus Strait.[57] This city became Constantinople, the new capital of the Roman Empire. Amid growing signs that the Roman Empire was overextended and struggling, Constantinople overshadowed the former capital of Rome as its population increased dramatically and imperial institutions relocated there.[57] Constantine also took the extraordinary measure of elevating the Christian church's bishop of Constantinople to a status equal to the bishop of Rome.[57] This grew into a concept called "autocephaly", where regional leaders within the Christian church have a large degree of independence from each other.[58] This would cause some, uh, political problems later on.

Byzantine Empire[edit]

Legacy of Rome[edit]

In 395 CE, the Roman emperor Theodosius recognized that the empire had grown far too large to govern as a whole; he divided it between a western half led by Rome and the eastern half led by himself in Constantinople.[59] The western half's decline during Constantine's reign was now combined with Theodosius' new policy of cutting it out to dry. In 410 CE, the city of Rome was sacked by Visigoth barbarians with no real response from Constantinople.[60] With the two halves of the empire no longer giving a shit about each other, the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE could no longer be avoided.

The Eastern Roman Empire continued just fine past this event, although its traditions and culture changed so dramatically due to the Greek dominance within it that historians now term it the "Byzantine Empire" in recognition of its unique status.[61] From the beginning, the Byzantine Empire was built around a Christian identity and viewed itself as the true center of the religion.

This caused a lot of friction with the bishop of Rome, who held that only the sees founded by Jesus' apostles were legitimate, which had obvious implications for the Byzantine Empire's religious center of Constantinople.[62] The bishop of Rome actually rejected the entire idea of autocephaly. Meanwhile, the Byzantine Empire controlled the other four preeminent cities of Christianity: Constantinople, Alexandria (in Egypt), Antioch (Christianity's first city), and Jerusalem. The bishops based in these cities were eventually held to be of the same status as the bishop of Rome, with all five being known as "patriarchs".[62] The four patriarchs and the pope in Rome increasingly started to ignore each other in continental passive aggression.

Byzantium reached its height under the emperor Justinian, who took power in 527 CE. He modernized the empire's legal code and briefly managed to reconquer much of the lost Roman territory in the west.[63] He also commissioned the Hagia Sofia, the single most famous building in Byzantine history, to serve as the seat of the patriarch of Constantinople.[63] On the other hand, Justinian's rule was relentlessly authoritarian, based on the belief that he was God's chosen representative on Earth.[63] His constant warring catastrophically weakened the empire thanks to the high cost of blood and treasure, and the emperor's extravagant construction projects didn't help the checkbook much, either.[63]

The long decline[edit]

The empire's weakness spurred more outsiders to attempt to take it down. In this atmosphere of crisis, Justinian's successor, Emperor Heraclius (who ruled from 610 to 641 CE), hiked taxes and divided the empire into a series of military districts (called themes) under the command of a strategos (army leader) who had absolute power within them.[64] This did fuck-all to change the empire's ultimate fate, but it did stave off the inevitable for some centuries.

Unfortunately, the empire was also wracked by internal struggles. They were, surprise, surprise, in large part caused by religion. Iconoclasm, or the destruction of religious images and relics, swept the empire as certain rulers and many people believed the empire was being punished for idolatry. The iconoclast controversy exposed and exacerbated societal problems within the empire, as wealthier Greeks supported the veneration of icons while poorer non-Greeks broadly opposed it.[65] It contributed to a breakdown in Byzantine political stability.

Meanwhile, military governors started to seize more land and wealth, leading to repeated civil wars against the emperor.[63] The empire also went to war repeatedly against the Persians, who had become their primary rivals.[66] Combined with the aftereffects of a horrible plague that broke out in the 540s, these wars greatly reduced the empire's population and wrecked its economy.[66] The empire more or less stopped functioning, and its tradition of cosmopolitanism and urbanization was halted by the population losses and the raids on cities during the Byzantine wars. Instead, the remaining Byzantine population spread into smaller, more fortified communities.[66]

It was a bad time for the empire to break down like that, as some dude called Muhammad united the Arabic tribes under some fancy new religion called Islam, and his followers began militarily expanding across the map. The Byzantine–Arab wars began, lasting from 780 to 1180 CE. Vast swathes of Byzantine territory were lost to the Arabs, including two of the holy cities, Jerusalem and Alexandria.[67]

Uh-oh, the Catholics are here[edit]

“”Better the Turkish turban than the papal tiara.

|

| —Attributed to Loukas Notaras, Byzantine grand admiral from 1444 to 1453.[68] |

If that wasn't enough disaster for the Greeks, religion also came around to fuck them an extra time for good measure. The empire's military defeats and the loss of two pentarchy seats had emboldened the pope in Rome to start throwing his weight around, but the other patriarchs weren't going to have it. In 1054, both sides were fed up, and Patriarch Michael Cerularius and Pope Leo IX gave each other mutual excommunications and fuck-yous.[69] The schism permanently severed Eastern Orthodox Christianity from Catholic Christianity. It was much worse because it alienated the Byzantine Empire from its fellow Christian powers at exactly the wrong time, leading to isolation and weakening.[70]

That isolation came at an awful time, as the empire faced an even more devastating invasion by Muslim Turkic conquerors from Central Asia. Starting around 1067, the Byzantine Empire suffered a long string of defeats at the hands of the invading Seljuk dynasty and lost much of its eastern holdings, including much of Anatolia.[71] This culminated in the Greeks suffering a devastating loss at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.[72]

Manzikert and its desperate aftermath threw the Byzantine imperial government into a panic, and its emperor wrote to Pope Urban II asking for help from his former Catholic friends.[73] The pope decided to help by calling the First Crusade in 1095; zealous Christians from western Europe answered the call and began marching through Anatolia.[74] The Catholics captured Jerusalem, but their armies behaved extremely poorly towards the Greek Orthodox population, and the Byzantines didn't get all of their lands back.[75] Reconciliation was further away than ever. Typical.

The Byzantines were less welcoming to the Catholics during the Second Crusade, fighting an actual battle against the Catholics.[76] But things really came to a head during the Fourth Crusade, when a financial misunderstanding combined with long-held religious resentments spurred the crusaders to attack Constantinople itself, sacking a Christian city in the name of Christianity in 1204.[77] The looting and destruction temporarily destroyed the Byzantine Empire and permanently weakened it.

In its place rose the "Latin Empire", a short-lived and oppressive Crusader state that occupied Constantinople and its surroundings.[78] The Byzantine Empire clawed back into existence after the Latin Empire's downfall, but it was a fragment of its former self, and most of Anatolia was occupied by the Turks. Catholics and Orthodox were also irreconcilably pissed at each other. The end draws near.

Fall of the purple phoenix[edit]

“”On the third day after the fall of our city, the Sultan celebrated his victory with a great, joyful triumph. He issued a proclamation: the citizens of all ages who had managed to escape detection were to leave their hiding places throughout the city and come out into the open, as they to were to remain free and no question would be asked. He further declared the restoration of houses and property to those who had abandoned our city before the siege, if they returned home, they would be treated according to their rank and religion, as if nothing had changed.

|

| —George Sphrantzes, resident of Constantinople during the 1453 siege.[79] |

The Crusades destroyed the Byzantine Empire's military power. Meanwhile, in 1299, one of the small Turkish states in Anatolia started to grow massive by gobbling up its neighbors. This state became the Ottoman Empire, using its centralized military to seize control of Anatolia and cross into the Balkans.[80] The Ottoman Empire also tore great swathes of land away from the Byzantines by 1400, reducing them to just Constantinople and its surroundings.

Since the Ottomans controlled the Balkans and Anatolia, it was only natural that they coveted Constantinople due to its strategic location on the Bosporus. The Byzantines got a lucky break when the Mongols invaded the Middle East, but this breathing room only lasted until the 1450s. During this time, the Byzantine emperors looked west for aid, but the popes and the Catholic world stipulated that they would only come to the rescue of the Greeks who adopted Catholicism.[79] While the emperors were amenable, the Greek population absolutely despised the Catholics and widely preferred to be conquered by the Turks than join the pope. In desperation, higher clergy managed to strike an agreement with the Catholics in 1439, but it was far too late to make a difference, and the agreement was still greatly unpopular.[68]

Constantinople, the city of the world's desire, the center of Eastern Christianity, and the last direct remnant of the Roman Empire, finally fell to the Ottoman onslaught in 1453 after a prolonged siege and bombardment by heavy cannon.[79] The last Roman emperor, Constantine XI Palaeologus, died in the battle. After allowing his armies to sack and loot the city for three days, the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II had it rebuilt to serve as the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman rule (the Tourkokratia)[edit]

How to govern the Greeks[edit]

The fall of Constantinople was quickly followed by the conquest of most of the rest of the Greek lands that remained free, leading to the centuries of Turkish rule known in Greece as the "Tourkokratia".[81]

The Turks were quickly confronted with the problem of how to govern a vast population of non-Muslims, having gobbled up most of the Balkans and almost the entirety of Greece. Luckily for everyone, the Ottomans considered Greek Christians to be "people of the book", meaning that members of an Abrahamic religion were entitled to a large degree of tolerance.[82] The Turks thus introduced the millet system to manage the large and diverse empire, organizing people by demographic group (or millet) and then allowing each group to manage many of its own affairs.[83] The Greeks were grouped in the "Roman millet" (alongside Romanians, Bulgarians, Serbs, and other Christians), which was led by the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople.[82]

By granting powers to the head of the Eastern Orthodox faith, the Ottoman rulers aimed to demonstrate their goodwill towards the Christians of the empire. In doing so, they extended even greater authority to church leaders than they had during the Byzantine era, extending to civil and religious affairs.[82] As tends to happen when religious authorities become powerful, though, the clergy became increasingly corrupt, and civil affairs became dominated by the demanding and issuing of bribes.[82] So it goes.

Inequality[edit]

Still, this is the late Middle Ages we're talking about, so things were hardly nice for Greek Christians. A Christian could not bear weapons or serve in the government and had to pay a special tax in exchange for the right to be free from military conscription.[82] Christians were banned from marrying Muslims, and their word in the court of law was legally inferior to that of a Muslim. Those who converted to Islam were forbidden from renouncing their new faith under the pain of the death penalty.[82]

Worst of all, though, was the devşirme system. This was the practice of forcibly recruiting and converting young Christian and Jewish men to serve as bureaucrats and soldiers in the empire, a practice which caused much resentment among communities but gave the new recruits positions of power and relative wealth.[84] The system created a new class in upper Ottoman society and government that acted as a counterweight to the traditionally powerful Turkish nobility.

Most famously, many of the boys raised under the devşirme system became janissaries, who were the Ottoman Empire's elite class of soldiers.[85] The janissary corps were noted for their strict discipline and total loyalty to the sultan, and they soon realized how important they were to maintain the Ottoman state. By the reign of Sultan Bayezid II (1481–1512), the janissaries started demanding higher and higher salaries in exchange for their continued service.[85] When sultan Osman II tried to reign in their power in 1622, the janissaries assassinated his ass and then started exercising tighter control over imperial policy.[85] By 1648, the devşirme system was basically over, as the Ottomans decided to rely on their own people to serve as janissaries to make the janissary corps more loyal.[86]

Resistance and resentment[edit]

There were multiple revolts against the Ottoman rulers of Greece by the Greek population, inspired by resentment against unequal and authoritarian governance and later motivated by patriotism and nationalism. Greeks often received aid from outside powers who hoped to destabilize the Ottoman Empire for their own purposes. Uprisings started after the Ottoman defeat in the 1571 Battle of Lepanto, a loss that finally debunked the appearance of Ottoman military invulnerability.[87] Revolts tended to fail due to their disorganization in the face of the more sophisticated Ottoman military.

The much larger threat, though, was that presented by the klefts, or bandits. Experiencing poverty under heavy taxation, many Greeks turned to crime, forming brigand bands and prowling the countryside to prey on Christians and Muslims.[82] There was a shitload of them, and despite their lack of political motivations, the Ottoman state's inability to stop them made the criminals a popular symbol of Greek resistance. The problem got so bad that the Ottomans tried to hire some criminal bands as armatoloi to protect the countryside.[87] Even this didn't work since an armatolos could return to banditry on a whim if he felt like the Ottomans weren't giving him a nice enough deal.

Rising nationalism[edit]

Over time, Ottoman governance grew increasingly harsh and arbitrary as the empire began to decay. Greek revolts became more frequent and were put down with more bloodshed.[88] The Ottomans also did their best to prevent the ideals of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution from reaching their Greek citizens. This failed, however, in large part due to the efforts of the growing Greek mercantile class.

Since ancient times, Greeks were known as able seamen, and this tradition served them in allowing many Greeks to become wealthy merchants under the Ottoman Empire.[89] The Greek merchants who traveled abroad could encounter foreign and modern ideas and bring them home (along with their profits, cha-ching!).

The first Greek nationalist was Rigas Feraios, born to a wealthy family before traveling to Vienna, Austria, in 1793 and learning of the French Revolution.[90] He became enamored with the hope that something similar could happen in the Balkans, but the Austrians eventually turned him over to the Ottoman authorities, who had him tortured and then executed in 1798.

The murder of Feraios only delayed what was becoming inevitable, though, as Greeks became more aware of nationalism while becoming more fed-up with Ottoman oppression. In 1814, a revolutionary organization called the Philikí Etaireía ("Friendly Brotherhood") was formed in Odesa (now in Ukraine) to unite the wealth and influence of Greek nationalist-minded merchants to spark an uprising.[91] They also likely had help from the Russian Empire, which was interested in seeing the Ottomans fall to internal problems.

War of independence[edit]

By 1821, the Philikí Etaireía's activities had paid off. One of the movement's leaders, Alexander Ypsilantis, assembled a small army of followers and invaded the Ottoman Empire from Russian territory in February of that year, suffering a rapid defeat but inspiring a broader uprising.[92] The Peloponnese went up in revolt, although the movement was still disorganized and facing a much larger and better-funded Ottoman force. While the Greeks could use the terrain of their homeland to their advantage, the Ottomans were able to bring Egypt into the war on their side, while the Greeks were hampered by infighting.[92] Athens fell to the Ottoman counterattack in 1826, leaving the independence uprising defeated.

In Western Europe and the United States, a resurgence in interest in the Greek Classics led many wealthy members of society to feel great sympathy for the independence movement.[93] Pro-Greek advocates, called "philhellenes", included notable figures like writer and aristocrat Lord Byron![]() of the British Empire, artist Louis Dupré

of the British Empire, artist Louis Dupré![]() of France, and poet-playwright Alexander Pushkin

of France, and poet-playwright Alexander Pushkin![]() of Russia. The Ottoman Empire also caused great disgust among the European powers by conducting numerous bloody massacres against Greek civilians in retaliation for the uprisings.[94]

of Russia. The Ottoman Empire also caused great disgust among the European powers by conducting numerous bloody massacres against Greek civilians in retaliation for the uprisings.[94]

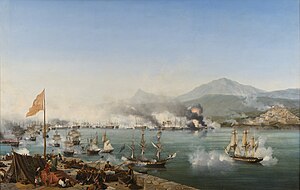

Under encouragement from the philhellenes, the United Kingdom, France, and Russia intervened on behalf of the Greeks in 1827 by sending a demand that the Turks lay down arms and agree to negotiate an autonomous state for Greece.[92] When the Ottoman government refused, European naval forces attacked much of the Turkish and Egyptian naval force near Pylos and won a decisive victory through superior firepower.[95]

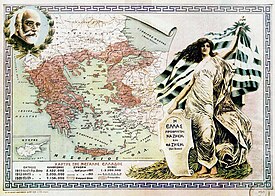

By destroying the Ottoman Mediterranean fleet and sending a French expeditionary force to the southern Peloponnese,[96] the European allies forced the Turks to evacuate southern Greece within ten months, creating the independent Kingdom of Greece in 1832 after long negotiations.[97] Unfortunately, central and northern Greece remained under Turkish domination. You will be unsurprised to see this was the source of many problems going forward.

Kingdom of Greece[edit]

“”Regretfully, we are bankrupt.

|

| —Charilaos Trikoupis, Greek prime minister, 1893.[98] |

Despotic monarchy[edit]

The great powers held a conference in London to choose who would lead the new Greek kingdom. The negotiations finally settled on a German prince Otto von Wittelsbach, son of King Ludwig I of Bavaria and a safely neutral choice since he wasn't particularly beholden to any of the great powers or Prussia.[99] The Greek people were not a party to the conference, but the hastily-assembled Greek legislature had little choice but to confirm him.

Otto proved to be a very shitty king. He ruled as an authoritarian, imposing heavy taxation and mandatory military service to build an army to fight the Turks and Egyptians for more Greek land.[100] That stupid plan managed to piss off the Greek people and alienate the great European powers, who didn't want to see more fighting in the Middle East. On the other hand, he managed to take a country dumped from centuries of foreign rule and establish a government with a legal code and civil administration.[101]

The Greeks and their new king also strove to redefine themselves as a new nation. That meant moving past the heritage of the Byzantine Empire and instead looking to focus on their own Greek identity.[102] Despite being a Catholic, Otto also made efforts to bind Greek identity with the Greek Orthodox religion, even establishing the Church of Greece as the nation's national religious body.[103]

New king, new problems[edit]

By 1862, the Greeks were fed up with their oppressive king and his incompetent, German-dominated government. A huge revolt that year forced the king to humiliatingly flee Greece onto a British warship, which took him into exile.[104] After a year, the great powers of Europe decided to replace him with prince Wilhelm of Denmark, who you'll notice came from a similarly inoffensive country. Wilhelm took the crown name George I and supported the promulgation of a new constitution that limited the monarchy's powers and granted most power to the national legislature.[105]

While Greece had a less shitty government, it still had severe problems. It was a poor country and largely undeveloped by the careless Turkish administration. The Greek government hoped to rectify that by borrowing vast amounts of money and investing it into infrastructure projects (like the famously troubled Corinth Canal[106]); unfortunately, this drove Greece into a humiliating bankruptcy in 1893.[98] Uh, where have we heard that story before?

Greece also had to deal with an increasingly heated language controversy over whether Demotic (meaning "peasant Greek")[107] or Katharevousa (an imitation of Ancient Greek seen as being more "cultured"[108]) should be the language of the state. This was an extremely controversial topic for several decades since the regular people of Greece couldn't understand Katharevousa while the upper class despised that Demotic had been greatly influenced by foreign languages.[109] During most of the Greek kingdom era, the government would put great efforts into shifting the population towards speaking Katharevousa. It was ultimately to be a failed effort.

There was, nice to say, an upside during this era of terribleness. Later in 1893, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a French aristocrat and sports enthusiast, assembled the Congress for the Restoration of the Olympic Games to revive the Ancient Greek tradition.[98] Since this was a Greek practice, the Congress felt it was only appropriate to hold the first games in Athens, Greece. While the government opposed the measure since there was no money for it, the Greek people and King George I greatly supported it to promote patriotism and revive Greek prestige. Thus began a remarkable peacetime mobilization where Greeks living domestically and abroad sent cash to fund the effort, eventually surpassing the cost estimate ten times over.[98] That's pretty impressive for a country still stuck in the donkey-and-cart era. The 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens were the first ever Olympic Games and were considered a great success.[110] Greece ended up with the greatest total of medals with 47, although the United States got the most gold medals (11 to Greece's 10).[111]

Military expansionism[edit]

While Greece ran into myriad internal problems, Greeks elsewhere still labored under Ottoman rule. From 1866, Greeks in Crete rose in a sustained popular revolt against the Turks, and the Greek kingdom's public broadly favored intervention.[112] Unfortunately for them, Greece's military was a pile of crap, and the country was in no state to go to war, even against the dying Ottoman regime. This sorry state of affairs persisted for quite a while, although Greece did get a nice little package of land as a gift from Russia in 1878 after the Russo-Turkish War.[113]

Still, it was inevitable that the irredentist Greeks would conflict with the Ottomans. This came to pass in 1897 when Greek public opinion finally convinced the government to declare war on the Turks over the issue of the Cretan uprisings. Greece did humiliatingly poorly in the war, with Greek forces being crushed by the Turks in two weeks and losing much of northern Greece to foreign occupation.[114] It makes sense then that in Greece, this war is known as "Black '97" (Μαύρο '97, Mauro '97) or the "Unfortunate War" (Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos).[115]

The short war had enormous consequences. An intervention by the great powers of Europe prevented Greece from losing much land and forced the Ottomans to allow Crete to become quasi-independent.[116] In return, though, Greece had to pay the Turks hefty war reparations. Both sides viewed the result as an indignity, hated each other for it, and viewed a future war to settle accounts as necessary and desirable.[116]

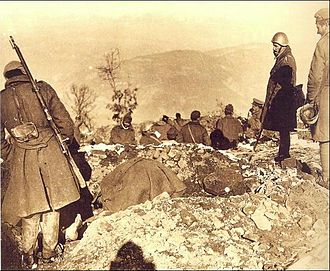

The Greek public and military members wanted war so bad that, in 1909, Greek military officers launched a popular coup to sweep militarists into power.[117] Elections in 1910 confirmed that their coup had popular support and led Eleuthérios Venizélos to become prime minister. Venizélos set about preparing for a new war, first by creating the Balkan League alliance with Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro and then reorganizing the army.[118]

In 1912, the Balkan League declared war on the Ottoman Empire, and this time Greece won victory while fighting alongside its allies with its renewed and modernized military.[119] The 1913 Treaty of Bucharest saw Greece nearly double in size and population by taking Crete and its northern regions.[120] Unfortunately, Greece's territorial claims overlapped with Bulgaria's, and the Second Balkan War broke out in 1913, leading to a catastrophic Bulgarian defeat.[121] That conflict turned Bulgaria against its former allies and against Russia, and it set the sides for what was to become the Balkans' bloodiest clusterfuck yet.

World War I (and other problems)[edit]

The bloodiest clusterfuck yet exploded in 1914 after Austria and Serbia got into a disagreement over Balkan hegemony that left Austria's heir to the throne assassinated. The war initially pitted the United Kingdom, Russia, and France (as the Triple Entente) against the German Empire and Austria (as the Central Powers). However, Greece soon had a compelling reason to oppose the Central Powers after the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria joined Germany's team.[122] Prime Minister Venizélos figured that if Greece could pull a sneaky gamer move by attacking Turkey and Bulgaria from the rear, Greece could snipe some extra territory from their old enemies in the peace deal. It also was a good idea to be on good terms with the UK, the world's dominant sea power, since the Greeks were a naval nation.

That's where the problems started. Greece's King Constantine I had an entirely different view since he had been educated in a Berlin military academy and was married to Kaiser Wilhelm II's sister.[122] What a soap-opera plot! With the king supporting a different foreign policy than the prime minister, the government became so hopelessly deadlocked that Venizélos finally resigned in disgust. In his place, the king appointed conservative politician Dimitrios Gounaris, who started cracking down on his liberal opposition.[122]

Unsurprisingly, the elections of June 1915 saw a disgruntled Greek public hand the pro-Venizélos liberals a parliamentary majority again, but king Constantine I managed to delay seating the new parliament for several months.[122] By this point, Venizélos had moved past being a warhawk and instead started touting the irredentist "Megali Idea", where Greece would annex large chunks of Anatolia, which had been lost to them since before the fall of the Byzantine Empire.

The new parliament reappointed Venizélos as prime minister and then declared war on Bulgaria, but king Constantine promptly forced Venizélos to resign and then appointed the conservatives to power again.[122] This stupid move caused a serious constitutional crisis, causing the country to descend into royalist vs. liberal street fights and even causing Venizélos to consider launching a civil war.[122] He launched a coup in 1916, seizing northern Greece, while the Entente powers blockaded Athens in the hopes of forcing the king's supporters to concede. By June 1917, the Entente was sick of the situation, and they gave an ultimatum to Constantine: either he would abdicate, or the Entente would invade Athens and abolish the monarchy.[122]

Constantine made the only choice he could make, and Venizélos returned to Athens to take control of Greece. He purged the royalists from the government and granted himself near-dictatorial powers for the duration of the war. In the spring of 1918, Greece invaded northwards into Bulgaria, resulting in a major victory.[123] The war in the Balkans ended not too long after that, but Greece had done enough to end up at the victor's table. Greece annexed Western Thrace from Bulgaria in the resulting treaties and received Entente assent for more annexations across Anatolia.[124] It seemed that the Megali Idea had come to fruition for a moment. Then reality set in.

Catastrophe in Turkey[edit]

With much of Anatolia in its grasp, the Greek government let it all slip away. Greece's new king abruptly died of sepsis caused by a monkey bite (no, seriously[125]), and Venizélos hastily called for new elections to renew his government's mandate. Instead, the war-weary voters swept the anti-war conservatives back into power, bringing back the old king Constantine I. The king started reorganizing the military and removing Venizélos loyalists from their posts, greatly weakening the military's command structure at a critical moment.[126]

While the Greeks made themselves weaker, the Turks surged back into a position of strength under the leadership of nationalist general Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. They rose up against the stipulations of the postwar peace in 1919, beginning the Second Greco-Turkish War. The unready Greek military leaders stupidly pursued the Turks into Anatolia's rugged interior, putting great strain on their own logistics.[126] They lost the Battle of the Sakarya in 1921, dooming the Greek war effort.[127] Kemal assumed leadership of Turkish forces and launched his own great offensive in 1922, hounding the disorganized Greek forces out of Turkey.

When Turkish forces reached the city of Izmir, they inflicted a crime akin to the Rape of Nanjing upon its residents, massacring around 100,000 Greek and Armenian citizens, desecrating ancient graves, and burning much of the city to the ground.[126][128] This war and the previous had occurred concurrently with the horrific Greek genocide, in which the Ottoman and Turkish governments massacred between 300,000 and 700,000 Greeks across Anatolia out of fear of potential disloyalty.[129] Through genocide and defeat, the Megali Idea died a bloody death.

Amid this horror, the Greek population of Anatolia fled from their homes in a massive panicked exodus. Between 800,000 to 900,000 Greeks had become refugees by the time peace was achieved in November 1922, putting enormous strain on the Greek kingdom.[130] The Republic of Turkey retained sovereignty over Anatolia, Eastern Thrace, and the city of Istanbul. Afterward, the two sides agreed to a population exchange in 1923, although it was more of a mutual forced expulsion of 1.6 million undesired people between them.[131] The Turks hoped to make permanent their internal victory over the Greek population, while the Greek state planned to provide for the refugees entering their country by seizing land from expelled Muslims.[132]

Political chaos[edit]

1922 coup[edit]

The disaster in Anatolia was almost immediately followed by a nice period of headless chicken mode in Greece proper. The military was almost universally disgusted with the poor conduct of the royalist government during the war, and they were determined to do something about it. On 11 September (not that one), 1922, the army and navy set out for Athens under arms while demanding that king Constantine abdicate his throne.[133] With such an imminent threat of overwhelming violence, Constantine had no choice but to flee the country for a second time.

A new government formed, promptly putting many of the pro-royalist military leaders on trial for incompetence during the war against Turkey; six would ultimately be sentenced to the death penalty and executed.[134] The new government then turned its sights on the monarchy, holding a referendum in 1924 and abolishing it after receiving overwhelming assent.[135]

Second Hellenic Republic[edit]

The new Greek republic, considered a successor to the provisional state established during the war of independence, promptly suffered another coup. In mid-1925, General Theodoros Pangalos marched on Athens and had himself installed as prime minister.[136] He became a dictator for about a year before being deposed by his own guard, and his actions greatly weakened the new government's legitimacy. He had also managed to jail over a thousand left-wing and democratic activists before his downfall, and these political prisoners were not released by anyone after him.[137] Instead, the Greek government cracked down even harder on the left-wing by passing a bill in 1929 that effectively criminalized trade union advocacy.[138]

1935 coup attempt[edit]

In 1933, a discontented public pushed the reformers out of power in the next round of elections and brought in the old royalists instead.[139] The Venizelists responded by attempting to launch their own coup against the government in 1935, but loyalist forces led by Georgios Kondylis crushed the uprising.[140] The Venizelist faction leaders, including Venizélos himself, were either exiled from the country on pain of death or else executed.

Without any real opposition, Georgios Kondylis took control of the government for himself, promising to restore the monarchy to provide political stability for the nation.[141] He held a new referendum with falsified results showing that the public supported a return of the monarchy by an absurd 98%.[142] This result allowed King George II to return to Greece and retake his throne, much to the fury of the republicans and leftists.[143]

Metaxas regime[edit]

George II immediately appointed the conservative military officer and politician Ioannis Metaxas as prime minister. A handful of months later, the king struck an agreement with Metaxas to shore up their power. With the king's support, Metaxas suspended the Greek constitution and declared himself dictator in 1936.[144]

Metaxas tried to model his regime off of the fascist states growing in Europe, establishing the National Youth Organization (EON), introducing a fascist-style salute, and attempting to build a cult of personality around himself.[145] Membership in the EON was very low, and Metaxas eventually made enrollment compulsory for Greek children. He also emphasized his aim of leading a national rejuvenation, a quintessentially fascist concept. However, Metaxas' "Third Hellenic Civilization" notably lacked the overt imperialist intentions of Hitler's Third Reich or Mussolini's Italian Empire, instead hoping to repeat ancient history by spreading Greek ideas and culture around Europe by technological and philosophical example.[146] In fact, Metaxas rejected conquest because he didn't want them damn dirty for'gners in his country.

On a much darker note, Metaxas ruthlessly crushed his opposition, especially leftists. Opposition figures were arrested, subjected to torture, and then either imprisoned or exiled.[145] Greece's communist party was quashed so hard that it stopped existing for a time. King George II notably did nothing to curb Metaxas' political violence, instead maintaining his support.[145] Royal complicity in the regime's crimes did much to discredit monarchism in Greek politics in the years ahead.

World War II[edit]

“”The Duce hasn’t the least idea of the differences between preparing war on flat terrain or in mountains, in summer or in winter. Still less does he worry about the fact that we lack weapons, ammunition, equipment, animals, raw materials.

|

| —Unhappy Italian general Quirino Armellini.[147] |

While Greece was a dictatorship under Metaxas, it maintained a close relationship with the United Kingdom through its king and wasn't about to join the Axis. Metaxas especially didn't like that Italy occupied some Greek islands, which Italy had captured from the Ottomans in 1912 and never handed over.[148] Amid deteriorating relations and Italian expansionism, Mussolini gave a speech in 1939 in which he claimed that Greece was colluding with Britain and France to restrict Italy's opportunities for imperialism.[149] Italy's annexation of Albania later that year threw Metaxas into a determined buildup of military strength as he realized that a fascist invasion was imminent.

Mussolini's attack finally came in October 1940. Stupidly, the Italian dictator believed he had caught the Greeks by surprise despite having trumpeted his enmity towards them for months and had Italian aircraft attack Greek ships on multiple occasions by this point.[147] Indeed, Mussolini's invasion was hastily-planned and went forth with less than half the manpower that Chief of Staff Pietro Badoglio had said would be necessary. The Italians ran immediately into bad weather, had their logistics disintegrate because of jammed ports, and bogged down in the Greek mountains.[147] Meanwhile, Metaxas, to his credit, successfully mobilized and motivated the Greek nation to resist the fascist attack.

The Greeks not only drove the Italians out of Greece but also invaded Albania. Nazi Germany finally intervened in April 1941 to bail out the Italians, but even they lost a great deal of time and resources.[150] Unfortunately, Greece still came under occupation, and its leader Metaxas died abruptly of throat inflammation, leaving the country rudderless.[151] Greek resistance groups were heavily divided by ideology, and they often fought each other as much as the Axis.[150]

Axis occupation came at a horrific toll on Greece. German troops ransacked food stores, stole livestock, and pillaged farms to feed themselves.[152] Greece's agrarian society, already on a delicate footing due to the reality of their landscape, almost immediately slid into a catastrophic man-made famine. In the winter of 1941-1942 alone, 40,000 Greeks died of starvation, while others resorted to eating cats, dogs, and wild greens to survive.[152]

The Axis also brutally punished the Greek populace for the actions of resistance groups. It was not uncommon for Axis forces to murder entire villages in reprisal for resistance.[150] Especially brutal were the Bulgarians, who hoped to colonize Thrace and Macedonia with their own population.[150] In the German occupation zones, around 40,000 Greek Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau to be murdered as part of the Holocaust.[153] Bulgaria also turned over about 4,200 Jews from its occupation zones to be murdered in Treblinka.[153]

Greece was ultimately freed when the Soviet Union's frontline got close in 1944 and convinced the Germans to flee for safer positions. Fearing that the Soviets would turn Greece into a communist stronghold, the British navally landed troops across the country to maintain their own order in the hopes of allowing King George II to return.[150] The partisan infighting, which had begun during the Axis opposition, only worsened once the Axis boot was lifted.

Civil war[edit]

“”The 1944 December uprising and 1946-49 civil war period infuses the present because there has never been a reconciliation. In France or Italy, if you fought the Nazis, you were respected in society after the war, regardless of ideology. In Greece, you found yourself fighting – or imprisoned and tortured by – the people who had collaborated with the Nazis, on British orders. There has never been a reckoning with that crime, and much of what is happening in Greece now is the result of not coming to terms with the past.

|

| —André Gerolymatos, Greek historian.[154] |

Greece immediately descended into the Greek Civil War, becoming one of the first showdowns in the wider Cold War. Communist guerrillas who had fought the Axis refused to cooperate in an Allied-brokered coalition government, and the capital city of Athens turned into a bloodbath in December 1944. This was notably the fault of the Greek government and the British, who armed Nazi collaborators and had their own soldiers fire on communist demonstrators across the city, sparking weeks of reprisals.[154]

Fighting paused for elections to be held in 1946, but the elections saw a conservative majority returned to parliament, which then voted to have king George II return.[155] The communists immediately rose again, and the strain of defending Greece proved too much for the ailing United Kingdom, which withdrew its forces and cut back on aid.

Unfortunately for the communists, they received almost nothing from Joseph Stalin, who was more interested in other parts of Europe.[156] Their only real advantage was being able to retreat across the border into neighboring communist Yugoslavia or Bulgaria,[156] a strategy that might sound familiar to you.

Under the Truman Doctrine, the US intervened because communist expansion must be prevented wherever it arises.[157] The US Congress appropriated $400 million for the Greek and Turkish governments as part of this effort, fearing that the Soviets were about to turn those countries into puppets in the Eastern Bloc. American weapons and advisors proved instrumental in rearming the Greek government.

Meanwhile, the communist Democratic Army of Greece rapidly escalated its brutality. They occupied villages in the mountains, demanding taxes and conscripts and shooting anyone they considered disloyal.[158] They also destroyed infrastructure, burned noncompliant villages, and made 250,000 people homeless.[158] Government troops responded with similar brutality. With this strategy being a success, the communist leaders became confident. And that led to them fucking up by deploying their troops to fight the government in the open. The Greek army, armed with American tanks and planes, easily bitch-slapped the communist partisan fighters, leading to a renewal of royalist determination and morale.[158]

Children perhaps fared the worst during the war, as the communists would abduct children and send them to be indoctrinated in the Eastern Bloc, and the government responded by forcing children into "Queen's camps" for similar indoctrination.[159] Greek children in the Eastern Bloc often never returned, and Greek children from Queen's camps were turned into fanatics who distrusted their parents.

The communists were fatally weakened by the split between Joseph Stalin and Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito, which resulted in Yugoslavia closing its border to them.[160] The Democratic Army furiously purged Tito loyalists from its ranks, weakening itself further. By 1949, the war was over with a royalist government victory. It came at a high cost, with about 158,000 Greeks killed in the fighting and brutality.[158]

Authoritarian era[edit]

Postwar reconstruction[edit]

Greece had been leveled by years of war, first against the Axis and then against its people. The US-funded Marshall Plan, which provided funds to rebuild Europe after the war, proved instrumental in helping Greece recover.[161] Confirming its pro-Western Bloc orientation, Greece sent troops to fight in the Korean War, and it then joined NATO outright in 1952 (amusingly and problematically, it did so alongside Turkey).[162]

The country's membership in the Western European Bloc shouldn't mask the fact that the Kingdom of Greece was relentlessly authoritarian. Its postwar political structure was entirely focused on excluding the left from the political process.[163] Economic development, while impressive, primarily benefited the rich and the aristocracy, although the country's overall quality of life increased.

Military dictatorship[edit]

There was brief hope for relief from authoritarianism when the moderate Georgios Papandreou won a great majority in parliament in 1964 from a disgruntled electorate; he promised some far-reaching social reforms.[164] This led him to clash with the conservative-minded King Constantine II and the king's backers in the military. The king's forced dismissal of the new government naturally caused several years of extreme political unrest from the people who had voted it into power.

Meanwhile, the military considered Papandreou a prime opportunity, denouncing him as a threat of dawning communism in Greece. To remove this threat, they preempted planned elections and launched a coup in 1967, seizing control of Athens and then arresting many key government figures.[165] King Constantine II's attempt at a counter-coup failed miserably, and he went into self-imposed exile.[166]

What followed was a wave of state terror. About 10,000 prominent leftists were immediately arrested, their names being put on a list before the coup.[167] Most of them were sent to a concentration camp on Yaros island, while the really unfortunate were tortured mercilessly to serve as an example to the rest.[167] The Yaros facility had been built as a brutal military prison during the civil war, and the junta reopened the facility to force even pregnant women and other dissidents to undergo forced labor and reeducation.[168]

The junta suspended Greece's constitution, banning the right to freedom of speech and imposing draconian censorship rules on radio, newspapers, and then television.[167] The regime hired or forced a great portion of the Greek population to serve as informants, to the point where anyone could be arrested if they were simply denounced by one of their neighbors.[167] East Germany, anyone? Even labor strikes and public gatherings were banned, with only church meetings still permitted.[169] Greece became a closed society, ruled by fear and suspicion. Political opponents would simply disappear, having been whisked away to an island prison or outright murdered.

Despite this brutality, the US and UK quickly declared their recognition of the new regime and continued foreign aid. Amid criticism, the US Secretary of State Dean Rusk announced that the Truman Doctrine prevented the US from interfering in Greece's internal affairs, which was as laughable then as it is today.[170] Greece's rulers, soldiers, and police did their torturing and murdering with impunity, declaring to their victims that they did so with US and NATO backing. For foreigners and the US, the junta put on a friendly façade and announced that Greece was forever safe for foreign investments, especially in the tourism industry.[170]

The regime finally started to fall when students of the National Technical University of Athens rose in 1973 to demand immediate elections. The military cracked down ruthlessly on the demonstration, arresting thousands of people, wounding hundreds, and murdering 24.[171] This massacre marked the end of the regime, as some less murderous officers deposed dictator Georgios Papadopoulos to prevent an outright war.[169] They allowed elections to go forth in spring 1974.

Third Hellenic Republic[edit]

Restoration of democracy[edit]

Conservative democratic statesman Konstantinos Karamanlis returned from overseas to head a transitional government in 1974. He dedicated himself to the daunting task of re-establishing civilian authority over the military and rebuilding faith in the Greek constitution.[172] He also had to deal with the irresponsible military junta that had brought itself to the brink of war with Turkey, a diplomatic situation he luckily managed to defuse. Most significantly, though, he promulgated a new constitution in 1975 that established a presidential system and held a referendum that abolished the Greek monarchy once and for all.[172]

Under Karamanlis, the democratic government finally put the military junta fuckheads on trial for crimes against humanity and treason. There were three trials, first for the ones who overthrew democracy in 1967, then for the ones who brutally suppressed the Athens Polytechnic uprising, and finally for the ones who engaged in torture and other crimes against the Greek people.[173] The trials exposed deep corruption, pettiness, and incompetence in the regime and helped destroy the myth of the authoritarian strongman in Greece.[174] They were also the first proceedings since the Nuremberg Trials to tackle the issue of institutionalized torture.[175]

Modernization[edit]

Karamanlis' final years in office were capped by the accession of Greece to the European Economic Community, which it had been kicked out of after the military takeover.[172] Investments from Europe and growing revenues from tourism helped modernize Greece's economy and further boost its standard of living. In 1981, the right-wing party lost in favor of the social democratic PASOK party, led by Andreas Papandreou. Even the historically volatile relationship with Turkey improved after a series of earthquakes in 1999 caused an outpouring of mutual empathy and aid from the citizens of both countries.[176] Sometimes people aren't bastards.

In 2001, Greece adopted the euro. In 2004, it had the honor of hosting the Olympic Games in Athens again, and the games left the city with significantly improved infrastructure and transportation.[177]

Unfortunately, all was not well. Greece's economic growth had stagnated, and there were deep divisions between social democrats and conservatives on managing this problem.[178] Relations with Turkey also soured again in 2006 when Greek and Turkish fighter jets somehow managed to crash into each other during a longstanding dispute over national airspace.[179]

The shitty economy also left much of the young generation with no prospects and bitterness towards the government. After the killing of a young man by police in 2008, many cities across the country exploded into rioting.[180]

The great debt fuckup[edit]

“”I'm the Finance Minister of a bankrupt country.

|