Melodrama

“”Salty Sam was tryin' to stuff Sweet Sue in a burlap sack.

He said, "If you don't give me the deed to your ranch, I'm gonna throw you on the railroad tracks! |

| — ---Along Came Jones, by The Coasters |

| You gotta spin it to win it Media |

| Stop the presses! |

| We want pictures of Spider-Man! |

| Extra! Extra! |

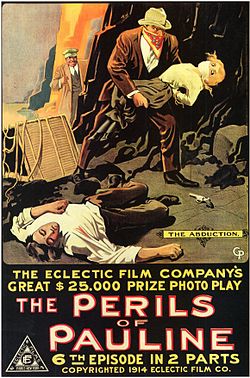

A melodrama, in the broadest sense, is a serious drama that can be distinguished from tragedy by the fact that it is open to having a happy ending. In practice, it is a rather pejorative term. In melodrama there is constructed a world of heightened emotion, stock characters, and a hero who rights the disturbance to the balance of good and evil in a moral universe. The term literally means "music drama", since music was used to increase the emotional response or to suggest characters. There is a neat structure or formula to melodrama: A villain poses a threat, the hero escapes the threat (or rescues the heroine) and there is a happy ending.

History[edit]

Melodrama, in its historical sense, was a sort of play with a romantic, sensational plot which also contained songs or music used as interludes. The word itself is a portmanteau of melody and drama. In 1775, Jean-Jacques Rousseau produced a play, Pygmalion, in which music was played to accompany certain scenes and the spoken words of the actors. The addition of songs to plays together with spoken passages was, of course, the beginning of musical theater, the operetta, and the German Singspiel.

Issues melodrama[edit]

In current usage, the sensationalistic plots of these original melodramas have swallowed up the other senses of the word. Melodrama as currently used is a mildly pejorative word in literary and other sorts of criticism, meaning a drama primarily characterised by sensational plots and blatant emotional appeals to conventional sentiment, but which is typically distinguished from tragedy by often having a happy ending. When melodrama is used in the pejorative sense, it is usually because the critic feels that the sensationalism of the plot lacks realism, or that the characters are stock heroes and villains with little room for characterization. Melodrama is ubiquitous on television: it is evident, for example, in a long series of TV movies about diseases or domestic violence, or the large number of hour-long television programs about lawyers, police officers, or physicians.

Issues melodrama is a subspecies of melodrama in which current events or politics are given a dramatic treatment, hoping to use some recent crime or controversy as a vehicle to draw an emotional response from the viewer. The usual method is to involve lawyers, police officers, or physicians, who can then make spit-acted![]() speeches about the crime or controversy being dramatized. By this artifice, the dramatist seeks to engage the audience's recently refreshed sense of fear or moral disapproval, while simultaneously maintaining the posture that the drama so produced is timely and socially engaged. Cop shows were better when they were about babes, car chases, gunfights, and explosions. A steady diet of police procedurals reinforces heroic narratives about police and severely underrepresents incidents of police racism, and encourages authoritarian attitudes and a casual attitude towards the rights of citizens.[1]

speeches about the crime or controversy being dramatized. By this artifice, the dramatist seeks to engage the audience's recently refreshed sense of fear or moral disapproval, while simultaneously maintaining the posture that the drama so produced is timely and socially engaged. Cop shows were better when they were about babes, car chases, gunfights, and explosions. A steady diet of police procedurals reinforces heroic narratives about police and severely underrepresents incidents of police racism, and encourages authoritarian attitudes and a casual attitude towards the rights of citizens.[1]

Action melodrama is another subgenre of melodrama that is particularly prevalent in the action Hollywood film blockbuster. An athletic action hero is pitted against an evil villain, and through a bevy of fights, car chases, love scenes and splatter, the hero overcomes the villain and restores the balance of good in the universe. This subgenre often includes a heroine who fights and loves with the hero. Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger are examples of the stars of these action melodramatic flicks.

Examples[edit]

“”One of these days I'm gonna stop my listenin'

Gonna raise my head up high One of these days I'm gonna raise my glistenin' Wings and fly But that day will have to wait for awhile Baby, I'm only a society's child When we're older things may change But for now this is the way they must remain I say, I can't see you any more, baby Can't see you anymore No, I don't wanna see you any more, baby |

| —- Janis Ian, Society's Child |

- The NBC network's series of Moment of Truth TV movies

were marketed towards an audience of American women; as such, Moment of Truth movies were invariably issues melodrama with stories told from a female perspective. Reruns of these TV movies were mainstays of the Lifetime cable channel as well. They often featured diseases such as alcoholism, or plots involving domestic violence, rape, adultery, or betrayal; however, the typical plot of such a movie required a happy ending typically achieved by some kind of social-work or therapeutic intervention.[2]

were marketed towards an audience of American women; as such, Moment of Truth movies were invariably issues melodrama with stories told from a female perspective. Reruns of these TV movies were mainstays of the Lifetime cable channel as well. They often featured diseases such as alcoholism, or plots involving domestic violence, rape, adultery, or betrayal; however, the typical plot of such a movie required a happy ending typically achieved by some kind of social-work or therapeutic intervention.[2] - The Law and Order series

of television series of police procedurals has run from 1990 to the present day. These typically put a police and law-enforcement oriented on themes loosely based on reports of crime or scandals ("ripped from today's headlines")[3] The intro to the original series said, "In the criminal justice system, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups: The police, who investigate crime, and the district attorneys, who prosecute the offenders. These are their stories." To be fair, earlier police dramas such as Dragnet and Adam-12 occasionally featured similarly topical themes, handled much more bluntly, concisely, and naively. This makes these older police procedurals much more entertaining to watch in the twenty-first century.

of television series of police procedurals has run from 1990 to the present day. These typically put a police and law-enforcement oriented on themes loosely based on reports of crime or scandals ("ripped from today's headlines")[3] The intro to the original series said, "In the criminal justice system, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups: The police, who investigate crime, and the district attorneys, who prosecute the offenders. These are their stories." To be fair, earlier police dramas such as Dragnet and Adam-12 occasionally featured similarly topical themes, handled much more bluntly, concisely, and naively. This makes these older police procedurals much more entertaining to watch in the twenty-first century. - In a sense, TV series such as Law and Order continue a long tradition of exploitation films

that treat subjects such as women in prison, juvenile delinquents, motorcycle gangs, beatniks, or drug addicts. These films hide behind moral judgmentalism and a pretense that they are addressing serious social issues to present deliberately titillating material.[4]

that treat subjects such as women in prison, juvenile delinquents, motorcycle gangs, beatniks, or drug addicts. These films hide behind moral judgmentalism and a pretense that they are addressing serious social issues to present deliberately titillating material.[4] - Judy Blume, the "Jacqueline Susann

of children's literature"[5], introduced themes such as racism

of children's literature"[5], introduced themes such as racism . menstruation

. menstruation , masturbation

, masturbation , and bullying

, and bullying to children's literature, all soaked in the sort of heavy moral earnestness that seeks to deflect questions as to whether such themes are age-appropriate for children's reading.[6] A better question to ask would be, "is this really entertaining?" If your children prefer that sort of thing to Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, or Batman, you probably ought to worry.

to children's literature, all soaked in the sort of heavy moral earnestness that seeks to deflect questions as to whether such themes are age-appropriate for children's reading.[6] A better question to ask would be, "is this really entertaining?" If your children prefer that sort of thing to Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, or Batman, you probably ought to worry. - Blume's body of work falls within a broader tradition of melodramatic social novels for young adults, including S. E. Hinton

and her The Outsiders (1967) and That was Then, This Is Now (1972), and the recent TV series 13 Reasons Why

and her The Outsiders (1967) and That was Then, This Is Now (1972), and the recent TV series 13 Reasons Why . Perhaps the most notorious book in the genre is Beatrice Sparks's anonymously-published Go Ask Alice

. Perhaps the most notorious book in the genre is Beatrice Sparks's anonymously-published Go Ask Alice (1971), a fictitious cautionary tale that was initially claimed to be an actual diary of a teenaged girl who is slipped LSD and eventually dies of an overdose. Notwithstanding this book's origin as anti-drug propaganda, it too is a frequent target of censorship campaigns.[7][8][9]

(1971), a fictitious cautionary tale that was initially claimed to be an actual diary of a teenaged girl who is slipped LSD and eventually dies of an overdose. Notwithstanding this book's origin as anti-drug propaganda, it too is a frequent target of censorship campaigns.[7][8][9]

“”I'm going to write a young-adult novel about drug abuse. It's easy. I've read three and think I know how to do it: The narrator must feel oppressed by parents either distant, alcoholic or both; have a shrink, who does no good whatsoever; get turned on to drugs unsuspectingly; run away from home; descend into prostitution or dealing; and think and write in bad coffee-shop stream-of-consciousness prose. Short, diary-entry chapters should begin or end with references to countercultural artists (Lewis Carroll, Jefferson Airplane, the Buzzcocks). At the end, a minor character assumes the narration to report the death of our previous narrator.

|

| —John Oppenheimer, Just Say Uh-Oh |

Effects[edit]

A steady diet of TV issues melodrama and police procedurals has been related to fear of crime and general political authoritarianism. These entertainments are also more attractive to authoritarian personalities, and give rise to distorted perceptions about how real-world policing and the judicial system work.[10]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Color of Change Hollywood & USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center (January 2020). "Normalizing injustice"', Feb. 2020.

- ↑ Richard B. Armstrong, Mary Willems Armstrong, Encyclopedia of Film Themes, Settings and Series (McFarland, 2000; ISBN 1476612307)

- ↑ Ripped from the headlines - Law and Order wiki

- ↑ V. Vale and Andrea Juno, Incredibly Strange Films (RE/Search, 1986; ISBN 0-940642-09-3)

- ↑ Gay Andrews Dillin, Judy Blume; Children's Author In A Grown-Up Controversy, Christian Science Monitor, Dec. 10, 1981

- ↑ Top Ten Challenged Authors 1990-2004, American Library Association

- ↑ Go Ask Alice, Snopes

- ↑ 100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999, American Library Association.

- ↑ John Oppenheimer, Just Say 'Uh-Oh', New York Times, November 15, 1998

- ↑ Kenneth Dowler, Media Consumption And Public Attitudes Toward Crime And Justice: The Relationship Between Fear Of Crime, Punitive Attitudes, And Perceived Police Effectiveness. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 10(2) (2003) 109-126