Intersex

| Live, reproduce, die Biology |

| Life as we know it |

| Divide and multiply |

| Great Apes |

Intersex is an umbrella term for people born with unique "physical or biological sex characteristics (such as sexual anatomy, reproductive organs, and/or chromosomal patterns)",[1] that do "not seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male."[2] Even if a person is born with intersex traits, this may not be noticed until years later.[1]

According to Anne Fausto-Sterling, roughly 1.7% of all human births involve intersex babies.[3]

A response to Sterling's finding stated the definition "should be restricted to those conditions in which chromosomal sex is inconsistent with phenotypic sex, or in which the phenotype is not classifiable as either male or female." From this perspective, the prevalence of intersex is about 0.018%.[4]

However, this could be a way to present the data as if intersex people are a minuscule percentage of the population so as to dismiss their need for legal rights and protections.[5] The 0.018% figure excludes, for instance, people with Klinefelter syndrome![]() or Turner syndrome.

or Turner syndrome.![]() [4]

[4]

One can distinguish intersex people from transgender people, in that intersex individuals have natural physical sex ambiguity; whereas the ambiguity that may be present in a transgender person's body is usually artificially-induced (so long as neurology is excluded). The word altersex![]() describes the latter experience, but isn't widely used. Like transgender people, intersex people sometimes come to feel that they were assigned the wrong gender at birth, and seek to override that assignment. This is generally (but not always) distinguished from transness; some intersex people may have a trans and/or nonbinary gender identity, yet most do not.[6] This experience is sometimes cited to postulate that each individual has an intrinsic gender identity that cannot be wrongfully imposed.

describes the latter experience, but isn't widely used. Like transgender people, intersex people sometimes come to feel that they were assigned the wrong gender at birth, and seek to override that assignment. This is generally (but not always) distinguished from transness; some intersex people may have a trans and/or nonbinary gender identity, yet most do not.[6] This experience is sometimes cited to postulate that each individual has an intrinsic gender identity that cannot be wrongfully imposed.

Terms for non-intersex people include "endosex",![]() "perisex",[7] or "dyadic".[8] The term "endosexism"

"perisex",[7] or "dyadic".[8] The term "endosexism"![]() was derived from the first of these to refer to systemic discrimination against intersex people. Other words for prejudice and discrimination against intersex people include intersexism,

was derived from the first of these to refer to systemic discrimination against intersex people. Other words for prejudice and discrimination against intersex people include intersexism,![]() intersexphobia,

intersexphobia,![]() and interphobia.

and interphobia.![]()

Terminology[edit]

Intersex is not hermaphroditism[edit]

Individuals with an ambiguous sex were previously labeled as hermaphrodites;![]() however, this has since dropped out of use due to not correctly describing said individuals.[9] The Intersex Society of North America stated applying the terms "hermaphrodite" or "pseudo-hermaphrodite" to intersex people is "stigmatizing and misleading".[10] Unlike intersex, hermaphroditism is a biological condition in which an organism has fully functional reproductive organs of both sexes. This is common in some non-human animals such as the mangrove rivulus

however, this has since dropped out of use due to not correctly describing said individuals.[9] The Intersex Society of North America stated applying the terms "hermaphrodite" or "pseudo-hermaphrodite" to intersex people is "stigmatizing and misleading".[10] Unlike intersex, hermaphroditism is a biological condition in which an organism has fully functional reproductive organs of both sexes. This is common in some non-human animals such as the mangrove rivulus![]() fish and the giant African land snail (Lissachatina fulica).

fish and the giant African land snail (Lissachatina fulica).![]()

The ability to produce both gametes (and thus the possibility of self-fertilization) is unknown in humans, but it's at least known this is hypothetically possible, because some people with ovotesticular syndrome have been documented with their fertility intact.[11] If it has ever occurred, it has not yet been documented in the scientific literature. At least one example of self-fertilization in another mammal was observed in a 1990 case report about a domestic rabbit,[12] who was perhaps looking to emulate the sea bunny.![]()

The term "intersex" may also be applied to non-human animals, including mammals. See the Wikipedia article on intersex (biology). There is for example the freemartin.![]() Those animals aren't called "hermaphrodites", either, unless they meet the criteria above.

Those animals aren't called "hermaphrodites", either, unless they meet the criteria above.

Birth defect?[edit]

Short answer: No. Long answer: Not really. The U.S. CDC defines birth defect as a structural change that can affect nearly any part of the body, and they may affect how the body looks, works, or both.[13] While intersex falls under this definition, many intersex people dislike their bodies being seen as having birth defects or otherwise being "defective", partly because being classified and treated as such has led to the forced surgeries mentioned above. Side effects from such surgeries may include but aren't limited to: loss of sexual feeling and function, scarring, and sterilization.[14] In extreme cases, intersex individuals have been murdered over a perception they were "defective".[15]

The Australian state of Victoria's Department of Health states: "Intersex variations are not abnormal and should not be seen as 'birth defects'; they are natural biological variations".[16]

"DSDs"[edit]

Some people use the phrase "DSDs" instead of "intersex". It stands for "disorders of sex development". The term originated from American clinicians without almost any input from intersex people at all,[17]:21 and has been criticized in the intersex community.[18][19] One paper reported that 69% of intersex patients felt a negative emotional reaction to the use of the term.[20] Other research indicated that just 3% used the term as a self-description: "The gap between the popularity of the words 'intersex' and 'DSD' was so large that the research suggested that any imposition of the DSD label on this community in Australia would clearly be inappropriate, despite attempts to impose it elsewhere".[17]:95–96

In the same research, the alternative usage of "DSDs" as differences of sex development was only slightly more well-liked, with intersex respondents much preferring the word "intersex" or more personalized phrases such as "my diagnosis" and "my chromosomes".[17]:96 Other research found "intersex" to be the most preferred phrase among those it applied to, and "disorders of sex development" to be largely non-preferred; however, "differences of sex development" was said in that survey to be acceptable, even if it wasn't as preferred as "intersex".[21] Some intersex people have argued that even the "disorders" variant could acceptably be used,[22] though this is possibly a rarity, based on the above surveys.

ThisIsIntersex released a page comparing and contrasting the usage of the terms "DSD" and "intersex".[23] The group interACT Advocates for Intersex Youth also commented:

“”"Disorder of sex development" terminology has become commonplace across the medical profession, especially in the United States. However, many people with intersex traits reject this new terminology, citing the pathologization "disorder" implies. Yet, some people with intersex traits have accepted the term and find utility in it when attempting to understand their difference—especially when explaining it to others in their life. In recognizing the problems with "disorder" language, many of these folks have recently moved to modify DSD terminology by replacing "disorder" with "difference" allowing "DSD" to instead stand for "differences of sex development". … interACT maintains its longstanding position of accepting individual choice around terminology and identity, and will not dictate others' choices, nor ostracize those who choose to use "DSD" or various iterations when describing their own personal experience.

|

| —interACT Advocates for Intersex Youth[19] |

Advocacy[edit]

Intersex medical operations[edit]

Nonconsensual medical operations are commonly done to intersex individuals, mainly for cosmetic purposes, such as to make the body conform to society's concept of either male or female. Intersex operations have a history of doing more harm than good,[25][26][27] inflicting victims patients with lifelong issues because their sex ambiguity was too egregious. Opposition to medically unnecessary surgeries conducted on (often newborn) intersex youth is a central concern to intersex advocacy. The Third International Intersex Forum in 2013 called for "an end to mutilating and 'normalising' practices such as genital surgeries, psychological and other medical treatments through legislative and other means."[28] Doctors may pressure parents to subject their intersex child to these surgeries even when not medically necessary.[29] Intersex groups have successfully convinced some hospitals to cease performing these surgeries.[30] It is considered a matter of human rights, specifically concerning "bodily integrity,![]() physical autonomy, and self-determination".

physical autonomy, and self-determination".![]() [28] Intersex people who have nonconsensual surgeries performed on them may have had this fact hidden from them, which even further violates informed consent

[28] Intersex people who have nonconsensual surgeries performed on them may have had this fact hidden from them, which even further violates informed consent![]() and can cause more harm.[31]

and can cause more harm.[31]

Some reasons aside from cosmetic ones that have been cited for performing these surgeries "include managing parental distress, social stigma and even 'improving marriage prospects'".[32][33] A 2013 report by the Parliament of Australia highlighted, with consultation from intersex people, that these presumptions are misinformed and based on insufficient evidence. The Intersex Society of North America advised it was best to wait and allow an intersex person to decide for themselves what to do. Regarding stigma, the parliament reported: "Rather than altering the child, it was submitted that societal attitudes are in need of reform."[34]:68–70 Nonconsensual operations cause some intersex people to distrust doctors and avoid healthcare.[35] No one knows why!

Legal protection[edit]

To date, intersex people are not protected under law in most countries across the world.

An article in Washington Law Review argued the 2020 Bostock v. Clayton County![]() decision by the U.S. Supreme Court should logically grant intersex people anti-discrimination protections. This extends from the court's definition of "sex traits".[36]

decision by the U.S. Supreme Court should logically grant intersex people anti-discrimination protections. This extends from the court's definition of "sex traits".[36]

Symbols[edit]

External links[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October / End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge". Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. October 24, 2016.

- ↑ "What is intersex?". InterConnect.

- ↑ Fausto-Sterling, Anne (2008) [2000]. Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. Hachette UK. p. 53. ISBN 9780786724338.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sax, Leonard (2002). "How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling". Journal of Sex Research. 39 (3): 174–178. doi:10.1080/00224490209552139. ISSN 0022-4499. PMID 12476264.

- ↑ Hida Viloria (April 1, 2015). "How Common is Intersex? An Explanation of the Stats.". Intersex Campaign for Equality.

The most thorough existing research finds intersex people to constitute an estimated 1.7% of the population*, which makes being intersex about as common as having red hair (1%-2%). … Some groups use an old prevalence statistic that says we make up 1 in 2000, or .05%, percent of the population, but that statistic refers to one specific intersex trait, ambiguous genitalia, which is but one of many variations which, combined (as they are in medical diagnostics and coding), constitute the 1.7% estimate by esteemed Professor of Biology and Gender Studies, Anne Fausto-Sterling, of Brown University*. A similar, slightly higher, statistic was also reported in, “How Sexually Dimorphic Are We?”, by Blackless, et al, in The American Journal of Human Biology. … The erroneous belief that we are an extremely tiny percentage of the population is often used to dismiss our need for legal rights and protections. Thus, we encourage everyone — particularly allies and/or members of the press educating others about intersex people — to please use the information and prevalence statistic provided here to accurately do so.

- ↑ (May 18, 2020). "FAQ: Intersex, Gender, and LGBTQIA+". interACT Advocates for Intersex Youth.

- ↑ "Perisex". Queer Undefined: a crowdsourced LGBTQ+ dictionary, via the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Trans and intersex glossary" / Entry: "Dyadic". Oxford University LGBTQ Society.

- ↑ Dreger, Alice D.; Chase, Cheryl; Sousa, Aron; Gruppuso, Phillip A.; Frader, Joel (18 August 2005). ""Changing the Nomenclature/Taxonomy for Intersex: A Scientific and Clinical Rationale."" (PDF). Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "Is a person who is intersex a hermaphrodite?". The Intersex Society of North America.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Ovotesticular syndrome. (Section: "Documented cases of fertility".)

- ↑ Frankenhuis, M. T.; Smith-Buijs, C. M.; de Boer, L. E.; Kloosterboer, J. W. (1990-06-16). "A case of combined hermaphroditism and autofertilisation in a domestic rabbit". The Veterinary Record. 126 (24): 598–599. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 2382355.

- ↑ (February 25, 2025). "About Birth Defects". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ (July 25, 2017). "I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me". Human Rights Watch with interACT Advocates for Intersex Youth.

- ↑ Michele Benini (March 22, 2018). "Killed at Birth: the Slaughtering of Intersex Babies". Il Grande Colibrì.

- ↑ "Health of people with intersex variations". Department of Health (The Victorian Government).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Jones T, Hart B, Carpenter M, Ansara G, Leonard W, Lucke J (2016). Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-208-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Tony Briffa (May 8, 2014). "Tony Briffa writes on 'Disorders of Sex Development'". InterAction for Health and Human Rights.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "interACT Statement on Intersex Terminology". interACT Advocates for Intersex Youth.

- ↑ (May 11, 2017). "Term 'Disorders of Sex Development' May Have Negative Impact". and Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, via Newswise.

A study published in the Journal of Pediatric Urology found that people born with reproductive organs that are not typically male or female had negative views of the term "disorders of sex development" or DSD commonly used by the medical community to refer to these conditions. Affected individuals and their caregivers preferred the terms "intersex," "variation in sex development," and "differences of sex development." A majority of participants (69 percent) reported a negative emotional reaction to a term used during a medical visit, and 81 percent changed their care because of it.

- ↑ Johnson, Emilie K.; Rosoklija, Ilina; Finlayson, Courtney; Chen, Diane; Yerkes, Elizabeth B.; Madonna, Mary Beth; Holl, Jane L.; Baratz, Arlene B.; Davis, Georgiann; Cheng, Earl Y. (2017-12-01). "Attitudes towards 'disorders of sex development' nomenclature among affected individuals". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 13 (6): 608.e1–608.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.03.035. ISSN 1477-5131. PMID 28545802.

- ↑ Sherri Groveman Morris. "DSD But Intersex Too: Shifting Paradigms Without Abandoning Roots". The Intersex Society of North America.

- ↑ "Intersex is not DSD". ThisIsIntersex (NNID, Netherlands organisation for sex diversity).

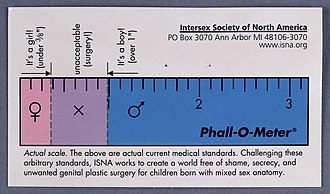

- ↑ (October 2014). "The “Phall-O-Meter”". InterAction for Health and Human Rights.

- ↑ Sexual health, human rights and the law. World Health Organization. July 20, 2015. ISBN 9789241564984.

- ↑ Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization: an interagency statement. World Health Organization. May 3, 2014. ISBN 978-92-4-150732-5.

- ↑ Discrimination and violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (United Nations). May 4, 2015.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 (December 1, 2013). "Malta Declaration / Public Statement by the Third International Intersex Forum". InterAction for Health and Human Rights.

- ↑ Julie Compton (October 24, 2018). "'You can't undo surgery': More parents of intersex babies are rejecting operations". NBC.

- ↑ Cathren Cohen (July 1, 2021). "Surgeries on Intersex Infants are Bad Medicine". National Health Law Program.

- ↑ Faye Kirkland (May 22, 2017). "Intersex patients 'routinely lied to by doctors'". BBC Radio 4.

- ↑ (April 2, 2015). "Malta the first country to outlaw forced surgical intervention on intersex minors". The Star Observer.

- ↑ Morgan Carpenter (April 2, 2015). "We celebrate Maltese protections for intersex people". InterAction for Health and Human Rights.

- ↑ (2013). "Chapter 3: Surgery and the assignment of gender". Parliament of Australia. Part of: "Second Report / Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia".

- ↑ Wang, Jeremy C; Dalke, Katharine B; Nachnani, Rahul; Baratz, Arlene B; Flatt, Jason D (2023-11-16). "Medical Mistrust Mediates the Relationship Between Nonconsensual Intersex Surgery and Healthcare Avoidance Among Intersex Adults". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 57 (12): 1024–1031. doi:10.1093/abm/kaad047. ISSN 0883-6612.

- ↑ Parry, Sam (2022). "Sex Trait Discrimination: Intersex People and Title VII After Bostock v. Clayton County". Washington Law Review. 97 (4): 1149.

- ↑ (July 5, 2013). "An intersex flag". interACT Advocates for Intersex Youth.

- ↑ "What does the yellow flag mean?". ThisIsIntersex (NNID, Netherlands organisation for sex diversity).

- ↑ "Intersex Symbols". Intersex Mapping Study (Dublin City University).

- ↑ (October 26, 2013). "Symbols". Intersex Day (InterAction for Health and Human Rights in collaboration with Brújula Intersexual).