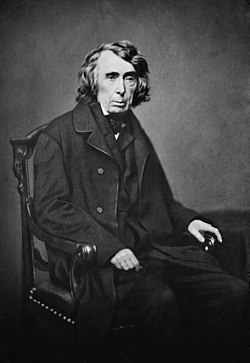

Roger Taney

| It's the Law |

| To punish and protect |

Roger Brooke Taney (March 17, 1777–October 12, 1864)[1] was a Supreme Court Justice from 1836 until his death in 1864.[2] Taney was appointed by then-President Andrew Jackson, whom he served as Attorney General and Acting Treasury Secretary,[note 1] where he was especially helpful during Jackson's feud against the Second Bank of the United States.[3] Taney even largely wrote Jackson's 1832 Veto Message,[1] where he explained why he felt a national bank was unconstitutional.[4]

Taney was the first Catholic to ever serve on the Supreme Court.[5]

The thing he is known for[edit]

Those who know the name Roger Taney in the modern era are almost certainly most aware of him due to his role in Dred Scott v. Sandford, for which he wrote the majority opinion.[1] The ruling "is widely considered the worst decision ever rendered by the Supreme Court,"[6] and is viewed as one of the major factors which led to the United States Civil War.[7] The decision ruled that black people aren't citizens, the Missouri Compromise, which "outlawed slavery above the 36º30' latitude line in the remainder of the Louisiana Territory"[8] was unconstitutional due to Congress not having the power to regulate slavery, and that slaves were property so the federal government was unable to take them away without just compensation.[9]

Even at the time, the ruling was incredibly controversial. "For all practical purposes, Northern courts and politicians rejected Scott v. Sandford as binding," writes one source.[6] The decision "outraged abolitionists, who saw the Supreme Court’s ruling as a way to stop debate about slavery in the territories."[10] One of the two Justices who dissented, Benjamin Robbins Curtis, even resigned from the Supreme Court largely because of his disgust with this very ruling.[9]

Why did Taney rule this way?[edit]

Taney's position on slavery is not what most people would expect; although he owned slaves early in his life, "He had freed the slaves he had inherited before he came to the Supreme Court" and had since come to the conclusion that the practice was an evil. Taney's nomination was also opposed by John C. Calhoun, of "a positive good" infamy,[11] along with "Cotton Whig" Daniel Webster[note 2] and Henry Clay, who, "time after time", one source writes, "chose to main and uphold" the institution of slavery.[13][1]

Essentially, those who liked slavery really didn't like Taney at first, although there was one notable exception: Andrew Jackson, who was known for his "support of slavery and participation in the slave trade."[14] Even if Taney wasn't personally the biggest fan of slavery, he still "inherited the conservative tradition of the Southern aristocracy and had supported [the notion of] states’ rights"[1] which allowed such defenses of slavery to flourish. Even if Calhoun didn't support him at first, he still managed to agree with the legal theory of "the Senate's most prominent states' rights advocate"[15] when it mattered most.

However, regardless of what Taney thought of slavery, he was, in the words of two recent scholars, "a proponent and defender of interconnected, even intersectional, racial ideologies; and second, Taney’s representativeness as an historian and as a legal realist describing law and politics as they were."[16] Essentially, he was a racist who believed "in a broader project of defining a 'Christian white person' as part of a 'master' race,"[17] even if he did not believe said "master race" should be enslaving others, along with a believer in the notion that the words of a law are only as important as the intent of those who wrote them. As Jeannie Suk Gersen noted in a 2021 article for The New Yorker:

The problem, though, was that, under the Constitution, in order to bring the lawsuit in the first place, one had to be a “citizen.” To arrive at the conclusion that Scott was not one, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney zeroed in on the statement in the Declaration of Independence that it was “self-evident” “that all men are created equal” and “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.” If the Founding Fathers intended to include Black people in that declaration while personally enslaving them, Taney reasoned, that would mean that the Founding Fathers were hypocrites who “would have deserved and received universal rebuke and reprobation.” But Taney found it impossible that these “great men” acted in a manner so “utterly and flagrantly inconsistent with the principles they asserted.” So he concluded, instead, that their intent was to exclude Black people from the American political community. Of the two possibilities, grotesque hypocrisy or white supremacy, Taney found the latter far more plausible.

Indeed, Taney, a former Maryland slaveholder, said the language of equality and rights “would not in any part of the civilized world be supposed to embrace the negro race, which, by common consent, had been excluded from civilized Governments and the family of nations, and doomed to slavery.” The “unhappy black race,” he wrote, was “never thought of or spoken of except as property, and when the claims of the owner or the profit of the trader were supposed to need protection.” Most notoriously, Taney wrote that Blacks were “regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” He also noted that the Constitution itself took slavery as a given in the fugitive-slave clause, and the slave-trade clause (Article One, Section 9, Clause 1 of the Constitution), prohibiting Congress to abolish the “Migration or Importation of such Persons” before 1808 and allowing an import tax of up to “ten dollars for each Person.” Taney took this as evidence that the country’s founding document did not confer on Black people “the blessings of liberty, or any of the personal rights so carefully provided for the citizen.”[18]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ His appointment for Secretary of Treasury was never confirmed by Congress. Although Jackson did attempt to get Congress to confirm him in 1834 "opposition to Taney and his financial program was so strong that the Senate rejected… marking the first time that Congress had refused to confirm a presidential nominee for a Cabinet post."[1]

- ↑ Cotton Whigs being a term used to describe members of the Whig party that "were pro-slavery or more cautious about freeing slaves because it would antagonize their southern Whig breathren and thereby endanger the union."[12]:624

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Roger B. Taney

- ↑ Chief Justice Roger Taney

- ↑ Roger B. Taney (1833 - 1834)

- ↑ Bank Veto Message (1832)

- ↑ Catholics and the Supreme Court

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Dred Scott decision

- ↑ How did the Dred Scott decision contribute to the American Civil War?

- ↑ Missouri Compromise (1820)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The Supreme Court Case That Led to The Civil War | Dred Scott v. Sandford

- ↑ Dred Scott Case

- ↑ John Calhoun on Slavery as a Positive Good

- ↑ Daniel Webster: The Man And His Time by Robert Vincent Reminin

- ↑ HENRY CLAY AND SLAVERY

- ↑ Why Andrew Jackson’s Legacy Is So Controversial

- ↑ John C. Calhoun: A Featured Biography

- ↑ Roger Taney: Intersectional Racist in an Age of Racist Differentiation

- ↑ Roger Taney: Intersectional Racist in an Age of Racist Differentiation

- ↑ The Importance of Teaching Dred Scott