War of 1812

| It never changes War |

| A view to kill |

“”The big losers in the war were the Indians. As a proportion of their population, they had suffered the heaviest casualties. Worse, they were left without any reliable European allies in North America ... The crushing defeats at the Thames and Horseshoe Bend left them at the mercy of the Americans, hastening their confinement to reservations and the decline of their traditional way of life.

|

| — Donald Hickey, The War of 1812, A Short History.[1] |

“”Till I came here, I had no idea of the fixed determination which there is in the heart of every American to extirpate the Indians and appropriate their territory.

|

| — Henry Goulburn, one of the British negotiators at Ghent.[2] |

The War of 1812 was a military conflict between the United States and the United Kingdom which lasted from 1812 to 1815, hence the name. Depending on who's looking at it, the conflict was either a backwater sideshow of the Napoleonic Wars or a full war in its own right. Although the war had some roots in the dispute over Britain's impressment of American sailors for the blockade of France, the most significant cause of war was the UK's supply of arms to the various Native American tribes who were fighting against the United States. The war was also responsible for some dramatic episodes in American history like the burning of Washington DC and the penning of the Star Spangled Banner.

The impressment of sailors issue became moot after Napoleon's abdication in 1814, and both sides signed the Treaty of Ghent later that year. There were no boundary changes. However, while the war may have been a draw on paper, in reality it was a major victory for the United States. This is because America's victories over the Indians during the war and the UK's changing priorities led London to completely abandon their indigenous allies, leaving them to the US's (lack of) mercy.[3]

Origins[edit]

[edit]

The ascension of the pro-French Thomas Jefferson to the presidency in 1801 caused trade and diplomatic relations between the United States and Great Britain to deteriorate.[4] Meanwhile, the Royal Navy began waylaying American ships to haul away individuals who (they alleged) were British deserters.[5] The Royal Navy operated "press gangs", which were legally empowered to conscript any British citizen into naval service, even if they happened to be found on a foreign ship.[6] Britain's need for manpower on warships was greatly exacerbated by frequent desertions, which frankly should have been unsurprising considering the British method of naval recruitment.[6] Deserters often fled to the United States to serve on American ships; this combined with the near-identical cultures of the two nations led to frequent instances where British commanders would wrongfully impress American citizens into service on British ships.[7] This, of course, led to popular outrage among the American populace, who viewed this as a deliberate attempt by the British to attack the new American nation.

Impressment is traditionally considered to be the primary cause of the war although it probably wasn't. After all, Britain's wars with France had been going on for decades. Yet Great Britain's maritime policies never resulted in war until the U.S. 1810 elections swept the so-called "War Hawks" into Congress. This group comprised Southerners and Westerners who longed to gain more land to exploit for agriculture, leading them to agitate first for war with Britain with a view to seizing the upper Midwest and possibly Canada.[8] Maritime disputes served as a useful pretext.

Indian wars[edit]

The northern Midwest, especially the modern-day states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, collectively known as the Northwest Territory, was the site of numerous clashes between the United States and various Native American tribes. The most significant of these was the Northwest Indian War,![]() a decade-long conflict with a British-backed confederation of Indian tribes that resulted in many humiliating defeats for the US military. Many Americans blamed the British for the troubles they had with the Indians, and both sides were very pissed off about this.[9] It was well known among the Americans that the British were supplying large quantities of weapons to the Indians. As a notable historian of the era writes,[10]

a decade-long conflict with a British-backed confederation of Indian tribes that resulted in many humiliating defeats for the US military. Many Americans blamed the British for the troubles they had with the Indians, and both sides were very pissed off about this.[9] It was well known among the Americans that the British were supplying large quantities of weapons to the Indians. As a notable historian of the era writes,[10]

“”There is ample proof that the British authorities did all in their power to hold or win the allegiance of the Indians of the Northwest with the expectation of using them as allies in the event of war. Indian allegiance could be held only by gifts, and to an Indian no gift was as acceptable as a lethal weapon. Guns and ammunition, tomahawks and scalping knives were dealt out with some liberality by British agents.

|

| —Julius W. Pratt |

Anti-British fervor was thus most intense on the frontiers, with people from the region convinced that their problems would end once the British were expelled.

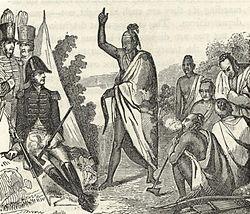

Meanwhile Tecumseh,![]() leader of the Shawnee, began a diplomatic initiative to unite all Indian tribes east of the Appalachians into a collective defense and negotiation pact in order to resist American encroachments on their territory.[11] Tecumseh's federation launched raids against American frontiersmen who trespassed on their land; legislators representing the US's western frontiers thus demanded a military response.[12]

leader of the Shawnee, began a diplomatic initiative to unite all Indian tribes east of the Appalachians into a collective defense and negotiation pact in order to resist American encroachments on their territory.[11] Tecumseh's federation launched raids against American frontiersmen who trespassed on their land; legislators representing the US's western frontiers thus demanded a military response.[12]

American expansion[edit]

Although it's debatable how significant American expansionism was as a cause for war, a significant segment of the American population was toying with the idea of annexing Canada and expelling the British from North America entirely.[13] Annexation was an especially popular prospect among northern frontier businessmen who wanted to fully control trade routes in the Great Lakes.[14] And, of course, removing British Canada would also remove British support for Native Americans, making them easier prey for American frontiersmen. Overconfident American politicians, most notably Thomas Jefferson, believed that the conquest of Canada would be "a mere matter of marching".[15] This, of course, was completely absurd given Canada's rugged terrain and the UK's powerful military.

Meanwhile, slaveholding southerners also had designs on Spanish-held Florida and were already expanding the institution across the southern portion of the Louisiana Purchase. It was noted at the time that the imbalance between Southern slave states and Northern free states could most easily be set right if Canada were made part of the Union.[16] Southerners also hoped that annexing Spanish Florida would allow them to finally destroy the raiding tribes of Creek and Seminole Indians.[17]

Woefully incomplete summary of the war[edit]

The American declaration of war barely scraped through the legislature by a margin of 79–49 in the House and 19-13 in the Senate.[5] The Federalist Party, mostly made up of New England merchant traders, accused the War Hawks of disguising base expansionism with claims of maritime abuses. This, as we see above, was entirely correct.

The United States military was small and poorly-trained, and the opening invasion of Canada was an embarrassing disaster in which American forces advanced about a dozen miles into Quebec before being forced back and finally surrendering Detroit.[18] An attempt to retake Detroit ended with a total loss, although the subsequent slaughter of American soldiers by Native Americans created a rallying cry among Americans for the remainder of the war.[19]

However, a turning point came in Canada with the Battle of the Thames. William Henry Harrison, previously known for fighting Native Americans at Tippecanoe, finished what he started and decisively crushed Tecumseh's Confederacy, killing the man himself, dissolving the Confederacy, and permanently shattering Native American strength in the upper Midwest.[20] Meanwhile, Andrew Jackson exploited internal divisions among the Creek Indians to crush them in battle and force them to hand over 20 million acres of land, about half of modern-day Alabama.[21] It's possible, however, that gaining Alabama just wasn't worth it.

After another abortive American attempt to invade Canada in 1814, the (temporary) end of hostilities in Europe allowed the British to shift their attention to North America. The war carried on despite the fact that the British were repealing their trade and maritime policies, essentially rendering the casus belli moot.[18] The British landed troops in Maryland, smashed the Americans in battle despite being outnumbered, and marched into Washington DC, burning most of America's government buildings.[22] After this, the British turned north to Baltimore, hoping to destroy the vital port city and thus force peace. However, the city was defended by the formidable Fort McHenry, which survived a 25-hour British attack and forced them to abandon their plans of taking Baltimore.[23] This victory inspired local lawyer Francis Scott Key to write the poem which would become the US national anthem.[24] So you'd better show respect and stand for the anthem!

After this, both sides came together to sign the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war. However, word didn't quite get around quickly enough. Andrew Jackson defended New Orleans from a British invasion in a brilliant but pointless battle that would earn him national fame and set him on the path to the White House.[25] For more information on how that would impact the Native Americans, see our article on the Amerindian genocides.

Peace, but not for the Indians[edit]

During the negotiations, the British demanded that the Americans respect the territory of their Native allies in the upper Midwest.[2] However, when push came to shove, the British agreed to abandon the Indians in exchange for American pinky-swears not to attack Canada. Although no losses of land were formalized by the treaty, it was still a disaster for the Native Americans. Without material aid from the British, Native Americans were unable to truly pose a threat to the United States. Indian wars, which had previously been full-scale struggles like the Creek wars or the Northwest Indian War, instead became little more than cleanup operations.

This stunning loss of power for the Natives also had another impact: on the American psyche. Rather than a conflict partner which must be taken seriously, Indians became barbarians and nuisances in the eyes of Americans. It was their powerlessness that allowed Americans to view them as inferior. Thus cognitive dissonance set in. In 1845, William Gilmore Simms wrote,[27]

“”Our blinding prejudices… have been fostered as necessary to justify the reckless and unsparing hand with which we have smitten [Native Americans] in their habitations and expelled them from their country.

|

| —William Gilmore Simms |

By 1871, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs declared,[28]

“”When dealing with savage men, as with savage beasts, no question of national honor can arise.

|

| —Francis A. Walker |

A century of war and extermination would follow.

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Calloway, Colin G. (1986). "The End of an Era: British-Indian Relations in the Great Lakes Region after the War of 1812". Michigan Historical Review. 12 (2): 1–20. doi:10.2307/20173078. JSTOR 20173078. 0890-1686

- Hickey, Donald R. (2012). The War of 1812, A Short History. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09447-7.

References[edit]

- ↑ Hickey 2012, Introduction. p. 22.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The Treaty of Ghent PBS.

- ↑ Calloway 1986, pp. 1–20.

- ↑ War of 1812–1815 US State Department Office of the Historian.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 War of 1812 Britannica.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Impressment of American Sailors The Mariner's Museum and Park

- ↑ The War of 1812: Stoking the Fires National Archives.

- ↑ War Hawk Britannica.

- ↑ Hitsman, J. Mackay (1965). The Incredible War of 1812. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 27.

- ↑ Pratt, Julius W. (1955). A history of United States foreign-policy. p. 126

- ↑ Tecumseh's Confederation Ohio History Central.

- ↑ Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T., eds. (1997). Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87436-968-1.

- ↑ Stanley, George F.G. (1983). The War of 1812: Land Operations. Macmillan of Canada. ISBN 0-7715-9859-9. p. 32.

- ↑ Nugent, Walter (2008). Habits of Empire:A History of American Expansionism. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-7818-9. p. 75.

- ↑ "The acquisition of Canada this year will be a mere matter of marching" National Park Service.

- ↑ John Roderick Heller (2010). Democracy's Lawyer: Felix Grundy of the Old Southwest. p. 98. ISBN 9780807137420.

- ↑ Benn, Carl; Marston, Daniel (2006). Liberty or Death: Wars That Forged a Nation. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-022-6.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 A Brief Overview of the War of 1812 American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ Battle of River Raisin American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ Cleaves, Freeman. Old Tippecanoe: William Henry Harrison and His Time. New York: Scribner, 1939. ISBN 0-945707-01-0 (1990 reissue).

- ↑ Battle of Horseshoe Bend American Battlefield Trust

- ↑ Battle of Bladensburg American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ Battle of Fort McHenry. '"American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ The Star-Spangled Banner National Museum of American History.

- ↑ Battle of New Orleans. American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Treaty of Fort Jackson.

- ↑ William Gilmore Simms quoted in Mitchell, Witnesses to a Vanishing America, p 255.

- ↑ The Indians of the Americas by John Collier (1947) W. W. Norton & Co. p. 124