Gender-inclusive language

| We control what you think with Language |

| Said and done |

| Jargon, buzzwords, slogans |

Gender-inclusive language is writing and speaking about people in a manner that does not use gender-based words.

Inclusive language has been a major platform of the feminist movement. Those who oppose it claim that the masculine form can be used to incorporate both genders; some believe that this should change, and some believe it's already starting to.

It has had a significant impact on Christian denominations, as the language of the Bible is almost exclusively male-focused. Versions of the Bible that use inclusive language have been produced, with varying levels of acceptance amongst the Christian community.

In more recent decades, some transgender and nonbinary people have also pushed for more gender-neutral language.

Gender-neutral pronouns[edit]

In English[edit]

Singular they[edit]

A very common example of inclusive language in English is the use of the singular they (or generic they). This is applying the words they or them, which are conventionally plural pronouns, as singular pronouns where him or her would otherwise be used, when talking about somebody whose gender is unknown or a generic "somebody."

For example, "if anybody asks me about it, I'll tell them they can try it for themself (or themselves)."

The singular they has been used in English literature for hundreds of years,[note 1] but is still a disputed point among some uptight prescriptivists, who see singular use of a plural pronoun, and especially variants such as themself instead of themselves, as a corruption of English grammar (though singular use of "themselves" seems to be more common than "themself").[note 2] Another issue is that while the "singular they" has a large degree of acceptance when referring to a generic person, it tends to look strange when referring to a named, specific person. For example, take the sentence: "When I found out who stole my phone, they're gonna wish they were never born!" vs. "Leslie called their friend yesterday to voice their concerns." The first sentence would not look out of place in typical speech, but the second one looks awkward to some people, and given the normal use of the singular they, one may have a hard time discerning the meaning. The second case is not usually an issue, as the gender of a specific person will be known in the vast majority of cases, but it presents a problem when being used as a gender-neutral pronoun to refer to non-binary-gendered individuals. Furthermore, in the trans community there tends to be a divide as to whether the "singular they" used in this manner is a gender-neutral pronoun that can be used for anyone or if it is specific to non-binary individuals and others who explicitly use they/them pronouns and use on a binary trans person is misgendering. For more information on alternatives to "singular they" when referring to these individuals, see the section "Neologisms" below.

In the context of the Bible translation issue that Hebrew and many other languages have historically used their equivalent of "he" as their generic pronoun rather than a neutral pronoun, such that a translation of these languages into English would have to choose between literally translating the male pronoun into "he" or translating the gender-neutral intent of the pronoun into "they".

When speaking in the third person, "one" is often used in this way, though it usually comes off as formal or overdone. ("One can starve to death if one refuses to eat".)

He/she[edit]

Another popular form is to use "he/she", "he or she", "him/her", "him or her", "(s)he", or "s/he", when gender is unknown. This usually extends to using "Dear Sir/Madam" as a form of address in letters where "Dear Sir" would otherwise have been the default historically, and other similar practices.

A flaw of the "he/she" formation is the assumption that a person must be either one or the other, and hence this language excludes those who do not conform to the traditional gender binary (such as those who choose not to identify with a gender). It's also awkward and somewhat limiting in its prosaic formality; as such, it is becoming increasingly phased out in many different contexts.

Neopronouns[edit]

Many neologisms have been created to fill the gap in English's set of third-person pronouns, or even possibly replace gendered pronouns altogether. These have been called neopronouns. Although most of them gained not much acceptance at present, some are more widely used:

- Spivak pronouns

, which were formed by chopping off the th of the third person pronouns (they, them, their, theirs, theirself). They are ey or e, em, eir, eirs, and eirself. Unlike they/them, these are typically conjugated as singular pronouns (e.g. "ey is doing well").

, which were formed by chopping off the th of the third person pronouns (they, them, their, theirs, theirself). They are ey or e, em, eir, eirs, and eirself. Unlike they/them, these are typically conjugated as singular pronouns (e.g. "ey is doing well"). - Ze or zie, hir or zir, hir or zir, hirs or zirs, and hirself or zirself, a set popular in the genderqueer community.

- Xe, Xem, Xyr, Xyrs, Xyrself, a derivative set of the ones above.[note 3]

While there is a significant group of people who use and advocate for gender-neutral pronouns, there is still some debate on which ones to use, creating an apparent lack of consistency likely harmful to getting any set or standard adopted by the greater populace. The respectful thing to ask is "what are your pronouns?" and then use them.

Other languages[edit]

In English, gendered language is confined to pronouns and to a few nouns generally referring to occupations (actor/actress, barman/barmaid, etc), family members (aunt/uncle, father/mother), aristocratic ranks (baron/baroness, duke/duchess, etc), and a handful of animals (cow/bull, mallard/duck, reynard/vixen, boar/sow, etc). The general trend has been to move away from gendered terms (when was the last time you heard comedian/comedienne?), and the masculine version of many is considered entirely appropriate for anyone (waiter/waitress, but referring to a woman as a waiter isn't going to raise any eyebrows). In some languages, almost every word is gendered, with all nouns and adjectives varying according to gender, and sometimes even verbs, although grammatical gender is not always related to biological sex or social gender, and some languages distinguish between animate and inanimate objects (sometimes the term "noun class" is used instead of "gender" where divisions do not approximate to sex).[5] In some languages, there is no concept of gender: examples include Finnish and Estonian, Malay and related languages, and Georgian.[6] Persian has two genders, common (for people of whatever sex) and neuter (broadly, for inanimate objects).[7] But even in languages with no gender it is still possible to be sexist, and the relationship between degree of gendering in language and degree of sexism in speakers is unclear (it is hard to extract language from other cultural factors).[8]

Deutsch (German)[edit]

German is strongly gendered by European standards, although it includes a neuter gender as well as masculine and feminine (famously, Mädchen="girl" is neuter). Hence one solution to gender-inclusive language is to use the neuter. An increasingly widespread replacement to gendered terms like Studenten=male students or students of unspecified gender/Studentinnen=female students is to use hybrids like Student(inn)en or StudentInnen - which works okay in official documents, but pronunciation is less clear. Some dialects of German have seen a reduction in genderedness, with Niederdeutsch using de=the for both male and female, in contrast to standard German der and die.[9] The German language is no stranger to successful language reform; see the German orthography reform of 1996![]() for an example.

for an example.

Français (French)[edit]

French divides all nouns into masculine and feminine, indicated by articles, adjectives, and some verb endings (in participles and the perfect tense); it also has male and female forms of many nouns. In addition, simply 1 man being in a group makes the pronoun ils which is downright absurd. French has historically used the masculine as all-inclusive gender but there has been a more widespread movement to use "male and female" instead of "(default) male" such as "les Français et les Françaises" (male French and female French) not "les Français" (male French considered as all-inclusive).[10] As with German, typographical tricks such as a centre dot can be used to create gender-neutral nouns like musicien·ne·s="musicians", instead of musicien (m) and musicienne (f); however this is controversial.[8] An unusual exception to this is the third-person direct pronoun son/sa/ses, which in English is his/her/its. This is because it changes not on the gender on the person, but the gender of the object in question. For example, "sa tablette" for his tablet and "son livre" for her book. This seems to be similar in other languages with strong Latin roots.

Italiano (Italian)[edit]

In Italian, to make gender neutral nouns and adjectives two main solutions are spreading among the supporters of inclusive language: the asterisk (*) and the schwa (ə). Both of these ways changes the end of a word, which most of the times carries the information about the gender of a person. E.G. "Bambino" (ending in -o) is a kid, "Bambina" (ending in -a) is a girl. Also, for the plural, Italian uses the masculine form to indicate a group of both males and females. E.G. "Bambini" (ending in -i) may signify both a group of kids, or a group of both kids and girls (it depends on the context). Thus, the asterisk and the schwa helps when you don't want to indicate the gender of the person. E.G. "Bambin*" or "Bambinə" may signifies a child, or a group of children regardless of their gender (it depends on the context). It's like the pronoun they in English: it can be singular or plural. Asterisk is easier to understand, but the schwa has the advantage of having a sound, so no solution prevails on the other. As in France, these two signs have met the opposition of the linguists and other intellectuals, who saw in them a degeneration of the language.[11][12]

Português (Portuguese)[edit]

Portuguese like all Romance languages such French and Italian divides all nouns as either between masculine and feminine. However the language notably the type that is spoken in Portugal, gender plays is even more important role as parts of the language are used in a way that includes possession. Many of the words in Portuguese for the female version of the role are simply the male version, but with -a instead of -o. Examples of this are; tia/tio (aunt/uncle), menina/menino (girl/boy), filha/filho (daughter/son), irmã/irmão (sister/brother) and amiga/amigo (friend). In Portugal, you put the gender place marker in front of a person's name whom you are talking about them, for example; A María José é... and O José María é... One interesting exception to this which come from Latin, is that there is a neutral term when you don't know the gender, isso é instead este and está.

There has been attempts especially in Brazil, to use alternatives like x instead of o or a, elu instead of ele or ela, and minhe(s) instead of meu(s) or minha(s). However, these are unofficial as these have not been agreed by the language regulator in Brazil, the Academia Brasileira de Letras.

Svenska (Swedish)[edit]

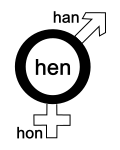

Sweden had a similar situation in the 1960s with English on gender-neutral language due to the strength of the feminist movement. So in Swedish to create a version of he/she (han or hans, hon or hennes), which is hen or hens, which originals through Finnish as the Finnish word for he or she is hän. However, its popularity didn't grow until in the later 2000s, which even then it still debatable among linguists.[13]

Íslandska (Icelandic)[edit]

Iceland is unusually notable in that a majority of the population don't have surnames. Instead people are known by their first name(s) and their patronymic e.g. Pál Jónsson, Pál, son of Jón (in the genitive case). If Pál had a son called Davíð and a daughter called Katrín, they would be known as Davíð Pálsson and Katrín Pálsdóttir. Quite often because there can easily be dozens of Pál’s, which it is local version of Paul, many Icelanders have more then one first name e.g. Pál Davíð Jónsson, Pál Davíð, son of Jón. When Pál Davíð Jónsson has a child, they would take the first part of name as their patronymic, e.g. if Pál Davíð Jónsson had a son called Jón Steinn, his name would be Jón Steinn Pálsson. If Pál was married to Helga, the children can easily choose instead to be known by the matronymic, as son or daughter of Helga instead, e.g. Davíð Helguson and Katrín Helgudóttir. This is quite common if the person was the child of a single mother.

Since the understanding of non-binary people has become much wider known, a new term has been created in addition to current -son/-dóttir system called -dur, literally child of, so if Jón Steinn registers themselves as non-binary on the population register, they can called Jón Steinn Pálsdur.

中文 (Chinese)[edit]

Mandarin Chinese is gender neutral in spoken form, tā. When written, there is a gendered third-person singular pronoun 它, with different forms for he 他 and she 她. However, this was only an early 20th-century innovation, probably in imitation of Western languages such as English, and previously a gender-neutral pronoun 他 was used. At the same time, equivalent moves to promote gendered spoken pronouns were never successful. There is now a movement to return to older, gender-neutral written forms as well.[14] 它 is typically used for non-humans and inanimate objects. In many apps and websites, the word they is simply written as "TA" (i.e. the pinyin for both 他 and 她).

日本語 (Japanese)[edit]

Japanese does not have many gendered features in its grammar, and because pronouns are seldom used, what gendered pronouns exist are not often encountered. However Japanese has a wide range of linguistic differences in vocabulary and style of speech that are traditionally gendered: men and women are supposed to speak in different ways, with men more abrupt and direct and women using more polite forms and honorifics, amongst other differences. More recently, these gender differences have become less common and people do not always speak in the way expected of their gender.[15][16]

Esperanto[edit]

In developing what was intended to be a universal second language, Esperanto's creator L. L. Zamenhof ended up being influenced by the fact that many of the languages that contributed vocabulary to Esperanto, like Polish, Yiddish and French, have female forms of pronouns and job titles. He and she became li and ŝi, while the word for waiter is kelnero and waitress is kelnerino. Since the mid 20th century, there has been a move to create gender-neutral terminology, like scrapping the female form of words. For the important gender-neutral pronoun, several options have been proposed; the first one is to use the word for it which is ĝi, the words ŝi and li have been combined to form ŝli, another option is to use the English-influenced singular they which is ili, an option common among Finnish Esperantists is ri.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ There is at least one example of singular "they" in the King James Bible (Deuteronomy 17:5).[1] Like this example, the Oxford English Dictionary also records earlier instances of singular 'they' dating back to 1375 CE that are used when "an antecedent that is grammatically singular, but refers collectively to the members of a group, or has universal reference."[2]

- ↑ Amusingly, Quakers in the 17th and 18th century used to say the exact same thing about the use of "you" to refer to a single person.[3][4]:294

- ↑ Though for the most part these "derivatives" are not so much distinct pronouns as spelling variations: xe, xie, zie and ze mean the same thing and are pronounced identically, approximately /tzee/, and differ only in spelling. The genderqueer community seems to have a consensus that the singular gender-neutral pronoun has the vowel /ee/ preceded by a sound that contains /s/ or /z/; putative pronouns that don't have this form (such as co, thon, or li) don't meet the consensus and so aren't generally accepted. A standardised spelling will probably evolve in time.

References[edit]

- ↑ Is "singular they" verbally and plenarily inspired of God? by Mark Liberman (August 21, 2006) Language Log, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ "they, pron., adj., adv., and n.", A.I.2.a., Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ That false and senseless Way of Speaking by Mark Liberman (July 1, 2016 @ 4:09 pm) Language Log, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ The History of Thomas Elwood by Thomas Elwood (1886) Routledge. Quoted in: The Varieties of Religious Experience, a Study in Human Nature by William James (1902) Longmans, Green, and Co. "Again, the corrupt and unsound form of speaking in the plural number to a single person, you to one, instead of thou, contrary to the pure, plain, and single language of truth, thou to one, and you to more than one, which had always been used by God to men, and men to God, as well as one to another, from the oldest record of time till corrupt men, for corrupt ends, in later and corrupt times, to flatter, fawn, and work upon the corrupt nature in men, brought in that false and senseless way of speaking you to one, which has since corrupted the modern languages, and hath greatly debased the spirits and depraved the manners of men; — this evil custom I had been as forward in as others, and this I was now called out of and required to cease from."

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Grammatical gender.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Gender neutrality in genderless languages.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Persian grammar.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 The Push to Make French Gender-Neutral by Annabelle Timsit (Nov 24, 2017) The Atlantic.

- ↑ Germans try to get their tongues around gender-neutral language: Justice ministry's edict that state institutions must use 'gender-neutral' language is forcing the country to confront change by Philip Oltermann (24 Mar 2014) The Guardian.

- ↑ French language watchdogs say 'non' to gender-neutral style: The Académie Française, France’s ultimate authority on the language, sparks national row after describing inclusive writing as an ‘aberration’ by Kim Willsher (3 Nov 2017) The Guardian.

- ↑ Italian intelligentsia launch petition against gender-neutral schwa symbol

- ↑ 'Politically correct' gender-neutral symbols 'endangering' the Italian language

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Hen (pronoun).

- ↑ A Gender-Neutral Pronoun (Re)emerges in China by Victor Mair (Dec 26, 201312:52 PM) Slate.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Gender differences in spoken Japanese.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Third-person pronoun.