User:LunaAHHHHH/sandbox2

Political spectrums or political echiquiers are heuristic representations of different political ideologies and how they relate to one another. It can function as a useful tool for understanding how different ideas, parties and people compare and differ but, like all heuristics, it is an over-simplification and one should be careful not to mistake the map for the territory.

The one-dimensional model[edit]

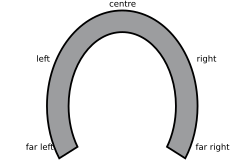

At its most basic, the political spectrum consists of a continuum from left to right, with varying shades of opinion in between. Usually, there are five political positions described in the one dimensional model: far-left, left-wing, centre, right-wing, and far-right, with the occasional inclusion of "centre-left" and "centre-right" groups.[citation needed]

A common way of characterizing the left-right spectrum is that the left tends to support equality while the right tends to support hierarchy, be it politically, socially or economically. Another common association is that the left tends to progress beyond the current status quo, while the right tends to preserve it. Historically, the origins of these associations came from the French Revolution, where those in the National Assembly who upheld revolutionary and egalitarian ideal sat on the left and those who supported the monarchy and the nobility sat on the right.[1]

One way to place the ideologies in the political spectrum are as follows:[citation needed]

Anarchism — Communism — Socialism — Social Liberalism — Centrism — Classical Liberalism — Conservatism — Monarchism — Fascism

Typically, leftist ideologies will be more critical of unregulated capitalism and its perceived issues regarding inequality and exploitation, seeking to heavily regulate it or abolish it altogether. Culturally, they tend to support various civil rights movements and measures to end social inequality and discrimination.[2] The right, meanwhile, tends to view capitalism and traditional cultural roles and notions more positively, believing them to be natural, inevitable, or even beneficial.[3]

Problems with a one-dimensional model[edit]

There are a number of problems with this model. One is that it flattens differences between a number of very different political schools of thought. For example, it groups together the Stalinists and anarchists on the left despite the former advocating for a repressive one-party state while the latter advocates for the abolition of all forms of rulership and subordination.[citation needed] Similarly, pro-capitalist libertarians who believe in bodily autonomy and are pro-choice, pro-drug liberalization, skeptical of the police, and anti-war can find themselves forced to rub shoulders with anti-abortion, pro-War on Drugs, cop-loving war-hawks,![]() which many of them resent.[citation needed] In other words, a single axis can often be unhelpful to actually determine the kinds of political positions one has.

which many of them resent.[citation needed] In other words, a single axis can often be unhelpful to actually determine the kinds of political positions one has.

Another problem is the similarities the two extremes can often have on the regular one-dimensional axis. For example, both fascism and Stalinism support an authoritarian regimes which brutally suppresses its opposition. In response, the horseshoe theory was formulated, which argued "the two extremes meet", with only the centre being the most distinct ideology between them all.[4]

However, this model ignores the differences which do exist between the different ideologies. In general, academic findings have disagreed with the horseshoe's conclusions.[5][6][7][8] In other words, it only further exacerbates the issue of oversimplification inherently present in a one-dimensional spectrum by not only grouping the ideologies of the same extreme, but of all the extremes. Additionally, it also ignores the similarities the centrists have with the extremists, including cases where the centrists helped fascist and other far-right regimes in cases where the far-left was ardently opposed to them.[9]

The two-dimensional models[edit]

Aiming to fix the issues of oversimplification with the traditional one-dimensional model, many have proposed the introduction of two dimensions. Two prominent examples will be shown, both categorizing ideologies based on their social and economic positions as separate axes.

Nolan chart[edit]

In the Nolan chart, created by the libertarian David Nolan, ideologies are placed according to two axes: "personal freedom" and "economic freedom". Traditionally, it's separated in four categories: the "liberal" (or "left"), which has high personal but low economic freedom; the "conservative" (or "right"), which has high economic but low personal freedom; the "libertarian", which has high for both freedoms; and the "authoritarian" (sometimes called "populist"), which has low on both.[10]

The way the model defines "freedom" is controversial. For one, it claims that liberals oppose "economic freedom". However, while they tend to support government interference in the economy, this doesn't necessarily mean the economy is less "free". Those on the right tend to have a more "negative" notion on freedom, while those on the left see economic freedom in the "positive" sense.[note 1] In this view, an economy in which the government is able to guarantee greater options and opportunities for the people through interventions would feature high economic freedom in this view. Conversely, a free and unregulated market economy would actually be less free as long as it failed to provide individuals with these opportunities.

The libertarian view on economic freedom can also spill to their views on personal freedom as well. Particularly, various libertarians have opposed protections for minorities against discrimination, as these would supposedly violate their libertarian principles of private ownership, i.e. the right for business owners to be bigoted. This hardly could consitute as support for "personal freedom", as it leads to a society where minorities are actively marginalized and excluded from public life.[12]

Political Compass[edit]

Another prominent example is the Political Compass, which is centered around two axes: economic and social. The social axis is based on an authoritarian-libertarian scale, where authoritarians support greater government control and restrictions on civil liberties, while libertarians oppose the two. The economic axis is based on the more traditional left-right scale, where the left supports a more regulated economy where the government makes the decisions, while the right supports economic deregulation and a free market.[13]

Problems with the two-dimensional models[edit]

While we can now make more satisfactory distinctions between liberals and libertarians, there are still ways in which these spectrums mislead us and misconstrue the nature of political difference.

Under these models, both anarchists and right wing libertarians are described as "libertarian" despite the fact that they have very different ideas about what that word means. Anarchists tend to support a more positive form of liberty that includes rights to things like food, medical care, education, and participation in decision making. For right-wing libertarians, their conception of liberty is more "negative" and is primarily a freedom from external interference.[citation needed] Right-wing libertarians typically do not believe that you have a right to food, medical care, education, or participation in decision making at your place of work.[citation needed] Yet despite these massive conflicts in their desired outcomes, intended policies, and contradictory understandings of what the word liberty entails, both the Nolan chart and the political compass understand both these movements as "libertarian"... which skips over a lot of important distinctions.

Another problem that should be considered is the way in which these models position "authoritarianism" as though it were a value that is actively endorsed. For Marxist Leninists (who typically score as authoritarians), quickly crushing the opposition is important to defeat the forces of reaction, who may be just as or even more tyrannical.[citation needed] Anarchists (who typically score as libertarians) during the Spanish civil war also imprisoned political opponents, established labour camps, and engaged in terrorism and summary execution: actions which are often defended across much the same lines that they were necessary to prevent fascists from getting the upper-hand.[14][better source needed] In these cases, similar measures and methods are endorsed in practice, but because Marxist Leninists are typically more open about what their revolution will involve, they get classed as "authoritarian", whereas the anarchists don't. The difference being not so much in what each group values, but in what they are willing to admit.[citation needed]

It is also worth noting that terms like "economic freedom" could be considered politically weighted.[note 2] Leftists might refer to it as "corporate authority" instead.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ "Positive freedom" sees liberty in terms of capabilities for pursuing a range of goals, while "negative freedom" sees liberty in regards to being free from external intervention.[11]

- ↑ It could also be argued that the idea of "complete economic freedom" tends to collapse into a farce in practice, as unrestrained businesses may engage in underhanded tactics to get ahead, making life very difficult for the lower classes and new businesses.

References[edit]

- ↑ Eldridge, Stephen (Mar 7, 2025). "Political spectrum". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on left-wing politics.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on right-wing politics.

- ↑ Mayer, Nonna (2011). "Why extremes don't meet: Le Pen and Besancenot Voters in the 2007 Presidential Election". French Politics, Culture & Society. 29 (3). New York: Berghahn Books: 101–120. doi:10.3167/fpcs.2011.290307. S2CID 147451564.

- ↑ Van Hiel, Alain (2012). "A Psycho-Political Profile of Party Activists and Left-Wing and Right-Wing Extremists". European Journal of Political Research. 51 (2). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell: 166–203. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01991.x. hdl:1854/LU-2109499. ISSN 1475-6765.

- ↑ Hanel, Paul H. P.; Haddock, Geoffrey; Zarzeczna, Natalia (2019). "Sharing the Same Political Ideology Yet Endorsing Different Values: Left- and Right-Wing Political Supporters Are More Heterogeneous Than Moderates". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 10 (7). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications: 874–882. doi:10.1177/1948550618803348. ISSN 1948-5506. S2CID 52246707.

- ↑ Hersh, Eitan; Royden, Laura (25 June 2022). "Antisemitic Attitudes Across the Ideological Spectrum". Political Research Quarterly. 76 (2). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications on behalf of the University of Utah: 697–711. doi:10.1177/10659129221111081. ISSN 1065-9129. S2CID 250060659.

- ↑ Pavlopoulos, Vassilis (20 March 2014). "Politics, Economics, and the Far Right in Europe: A Social Psychological Perspective" (PDF). The Challenge of the Extreme Right in Europe: Past, Present, Future. London: Birkbeck, University of London.

- ↑ Choat, Simon (12 May 2017). "'Horseshoe theory' is nonsense – the far right and far left have little in common". The Conversation. Melbourne. ISSN 2201-5639. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Nolan chart.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Economic freedom § Choice sets and economic freedom.

- ↑ Robinson, Nathan J. (July 19, 2020). "Why Libertarians Oppose Civil Rights". Current Affairs.

- ↑ "The Political Compass – a brief intro" by The Political Compass. Youtube.

- ↑ Casanova, J. (2005). Terror and Violence: The Dark Face of Spanish Anarchism. International Labor and Working-Class History, 67, 79-99. doi:10.1017/S0147547905000098