Holy Foreskin

| Christ died for our articles about Christianity |

| Schismatics |

| Devil's in the details |

“”Among the more bizarre attempts to account for the missing foreskin was that given during the late 17th century by the Catholic scholar and theologian Leo Allatius

|

| —T. Joyner Drolsum, Unholy Writ: An Infidel’s Critique of the Bible[1] |

The Holy Prepuce, or Holy Foreskin (Latin præputium) is one of the various relics purported to be associated with Jesus, this one being the one left over from his circumcision. At various points in history, a number of churches in Europe have claimed to own it, sometimes concurrently. Various miraculous powers of multiplication have been ascribed to it.

There are quite a few of these[edit]

The abbey of Charroux claimed to own the Holy Foreskin during the Middle Ages. It was said to have been presented to the monks by none other than Charlemagne, who in turn is said to have claimed (per the legend) that it had been brought to him by an angel (although another version of the story says it was a wedding gift from Empress Irene of the Byzantine Empire). In the early 12th century, it was taken in procession to Rome where it was presented before Pope Innocent III, who was asked to rule on its authenticity. The Pope declined the opportunity. Later, however, Pope Clement VII declared it to be a true relic, and granted an indulgence to pilgrims who went to visit it. At some point, however, the relic went missing, and remained lost until 1856 when a workman repairing the abbey claimed to have found a reliquary hidden inside a wall, containing the missing foreskin.

The abbey church of Coulombs in the diocese of Chartres, France was another medieval claimant. One story says that when Catherine of Valois was pregnant in 1421, her husband, King Henry V of England, sent for the Holy Prepuce. It was believed that the sweet scent that the relic was supposed to give off would ensure an easy and safe childbirth. According to this legend, it did its job so well that Henry was reluctant to return it after the birth of the child (the future King Henry VI of England).

The authenticity of the Holy Foreskin claimed by the St. John Lateran church in Rome is said to have been proven in 1527 when the troops of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sacked Rome. The relic fell into their hands for a time, and was allegedly put to the test by bringing a virgin girl before it, whereupon the foreskin enlarged!

Other claimants at various points in time have included (at least) the Cathedral of Le Puy-en-Velay (of lentil fame), Santiago de Compostela, the city of Antwerp, and churches in Besançon, Metz (Lorraine), Hildesheim (Lower Saxony), and Calcata (in Latium, Italy).

The foreskins today[edit]

Calcata is worthy of special mention, as the reliquary containing the Holy Foreskin was paraded through the streets of this Italian village as recently as 1983 on the Feast of the Circumcision (marked by the Catholic church around the world on January 1 each year). The practice ended, however, when thieves stole the jewel-encrusted case, contents and all, from the home of the local parish priest. The question of what happened to the foreskin remains mysterious: did the priest sell it, was it taken by thieves, or as Slate magazine suggested, was it seized by the Vatican to prevent this embarrassing ritual?[2]

Over the last century or so, the emphasis placed on relics by the Catholic church has declined markedly, with many relics with long traditions being relegated to "pious legend" by the Vatican. Interest in the Holy Foreskins has been specifically downplayed, with the observation in 1900 that these particular relics encouraged 'irreverent curiosity'. In 1900, the Vatican threatened excommunication for anyone who mentioned the Holy Foreskin, and after much debate, they refused permission to mention Calcata's relic in a 1954 tour guide.[2]

Assuming that it is possible that one of these foreskins is in fact Jesus Christ's, its preservation may raise the possibility of cloning when that technology is perfected for humans; compare Kahless.![]()

Theological implications[edit]

Traditional Christian belief has it that Jesus ascended bodily into Heaven at the end of his earthly life. This would mean that Jesus's foreskin (removed at his circumcision) would be one of the few physical remainders of Jesus left behind on Earth. It is important to note the methods used in Jewish circumcision around Jesus's time were not uniform, and were often less invasive. They did not become so until around the time of the revolt led by Simon bar Kokhba in CE 132-135. Thus modern, and probably medieval as well, ideas of what Jesus's foreskin would be like are/were somewhat anachronisticly off the mark. Nevertheless, there were some short-lived theological arguments as to whether Jesus can really be said to have ascended wholly into Heaven if this part of his body was actually missing; consensus was that his foreskin was no more an obstacle to this than the hair and fingernails that he had cut throughout his life.

A related theological issue questions whether Christ's foreskin was restored to him in his resurrection body. The act of circumcision was a ritual of profound religious significance to Jews, and marked their membership in the covenant community. The New Testament contains extensive discussions about whether circumcision was needed for Gentile converts, and concludes that it was not, however; Christ's crucifixion established a new covenant for Christians for which the rite was not necessary. When God achieves something by miracle, it seems arbitrary to propose limits to what that miracle can restore. In Mark 12:18-25, Jesus responded to the Sadducees'![]() question about marriage after the resurrection, saying that "When the dead rise, they will neither marry nor be given in marriage; they will be like the angels in heaven." (NIV) This suggests that the resurrected dead will have certain anatomical differences that may make the question moot.

question about marriage after the resurrection, saying that "When the dead rise, they will neither marry nor be given in marriage; they will be like the angels in heaven." (NIV) This suggests that the resurrected dead will have certain anatomical differences that may make the question moot.

Allegorical importance[edit]

Apart from its physical importance as a relic, the Holy Foreskin appeared in a famous vision of Saint Catherine of Siena. In the vision, Christ mystically marries her, and his amputated foreskin is given to her as a wedding ring.

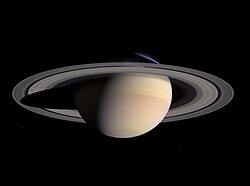

During the late 17th century, Catholic scholar and theologian Leo Allatius in the unpublished De Praeputio Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Diatriba ("Discussion concerning the Prepuce of our Lord Jesus Christ") speculated that the Holy Foreskin may have ascended into Heaven at the same time as Jesus himself and might have become the rings of Saturn, then only recently observed by telescope.

Voltaire, in A Treatise of Toleration (1763), ironically referred to veneration of the Holy Foreskin as being one of a number of superstitions that were "much more reasonable… than to detest and persecute your brother".[3]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Relics article from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Relics of Romanism article at the European Institute of Protestant Studies

- Sex in History, Mediaeval Sexual Behaviour

- The Holy Foreskin, Museum of Hoaxes

- David Farley, An Irreverent Curiosity: In Search of the Church's Strangest Relic in Italy's Oddest Town. (Penguin, 2009; ISBN 110110497X)

- David Farley, "Fore Shame". Slate, Dec. 19, 2006.

- George W. Foote and Joseph M. Wheeler, Crimes of Christianity, ch. 5: Pious Frauds (1887)

- John Calvin, Traité des reliques (1599)

References[edit]

- ↑ T. Joyner Drolsum, Unholy Writ: An Infidel’s Critique of the Bible. AuthorHouse, 7 November 2011, p. 227. ISBN 1456795759.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fore Shame, David Farley, Slate, Dec 19, 2006

- ↑ Voltaire, A Treatise on Tolerance. Archived from public.wsu.edu, 23 July 2011.