Luddite

| It just works Technology |

| Programming for Dummies |

“”Chant no more your old rhymes about bold Robin Hood

His feats I but little admire |

| —General Ludd’s Triumph[1]:273 |

“”If the Luddites had never existed, their critics would have to invent them. Those who favor indiscriminate industrial growth need an opposition that is just as indiscriminate in its hostility to industrialism — the better to score easy points.

|

| —Theodore Roszak[2]:viii |

The Luddites were a protest movement by workers during the Industrial Revolution, who expressed their objections to getting displaced by technology, industrialisation, and laissez-faire capitalism by sabotaging or destroying machinery. Contrary to popular belief, the Luddites were not explicitly 'anti-technology', rather their grievances stemmed from textile factories changing their working lives, many had previously produced textiles from home, meaning they went from being self-employed craftspeople, passing on their trade for generations, to drones working in hellish conditions for long hours and small pay in the very workplaces that had destroyed their livelihood.[3]:23-56 The origin of this anti-technology legend can be traced to Baron Thompson, who was involved in the prosecution of the Luddites in 1813. He had made a straw man argument to a grand jury that the Luddites were too stupid to understand the benefits of new technology.[3]:294-295

With today's societies being decidedly better off the world over, Luddites can look rather silly, at least if one sees their objections being to machinery itself. A more accurate interpretation of their actions would be as protest of the way capitalists were using machines to deprive the workers of their livelihoods. Today epithet of 'Luddite' has a negative connotation of someone who hates progress and/or technology, but it has been unjustly applied ever since the original Luddites because the technologists and entrepreneurs opposed all regulation of their industries starting in the Industrial Revolution. This has largely continued to present day, with CEOs calling Uber skeptics 'Luddites', even though Uber's business model was widely illegal (violating local taxi regulations).[3]:306-309

A crank could argue that, whereas the Luddites campaigned for unemployment compensation and re-training for those workers displaced by new machinery, they were amongst the most forward-thinking and progressive people of the Industrial Revolution. However, the term "Luddite" today is one of reproach, and does not carry connotations of being socially or economically progressive. There have been attempts to reclaim the term, but these Neo-Luddites still view modern technological civilization as an intractable harm that perpetuates rigid power structures at the expense of sustainability and solidarity.[4]

History[edit]

A precedent for the Luddites existed in the earliest years of the Industrial Revolution when there was resistance to displacement of cloth workers in the 1760s by the inventions of automated carding and spinning machines, occupations that were primarily held by women.[3]:206 The origin of the Luddites as a movement can be traced back to the British upper classes reacting to the outcome of the French Revolution that ended in 1799. The Reign of Terror (1793-1794) and the execution of Louis XVI (1794) had struck fear into the British nobility. The British government under the direction of King George III and leadership of Tory Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger rather than trying to make life better for the lower classes instead decided to crack down on free speech, freedom of the press, and political organizing. In 1799 and 1800, Parliament passed the Combination Acts, which banned trade unions (which had evolved out of the medieval trade guilds), the London Corresponding Society (a working class organization) and the writings of anti-monarchist Thomas Paine.[3]:13 The Combining Acts had the veneer of fairness,[3]:28 banning wage collusion both among workers and among business owners. In 1811, as family-owned and run cottage weaving industries were being squeezed by cheaper and faster businesses using increasing levels of automation, and before the Luddites had a name for themselves, Gravener Henson attempted to seek redress from business owners colluding on ever decreasing wages for their workers. Henson found out that despite how it was written, the Combination Acts did not apply in practice to business owners.[3]:28-31 Meanwhile in 1811, as craftspeople were becoming impoverished, George III entered a long and final phase of mental incapacity, his eldest son became Prince Regent (later becoming King George IV). The Prince Regent had no interest in politics, but great interest in living in opulence, including massive parties for British and exiled-French nobility as well as British Parliamentarians.[3]:41-44 At one such party, the line of guests' carriages was so long and congested that it gave opportunities for plebeians standing by the side of the road opportunities for cat-calling.[3]:41

According to one folkloric account, the movement was inadvertently started by an English "simpleton" named Ned Ludd, who in 1779 destroyed some stocking frames,[5]:923 after being criticized for not working hard enough and after being whipped by his employer.[3]:17 His name subsequently became associated with the "Luddite Riots" of 1812 to 1818. Though Ludd is unlikely to have existed, his legend became the equivalent of a modern-day meme.[3]:17 Belying the "simpleton" epithet, numerous letter and handbill authors writing under the nom de plume of Ned Ludd starting in 1811 showed both literacy and intelligence in their writing,[3]:66-68 causing one to wonder whether the simpleton epithet was just factory owner and ruling class propaganda as was suggested in an editorial in the December 7, 1811 Leeds Mercury.[3]:72

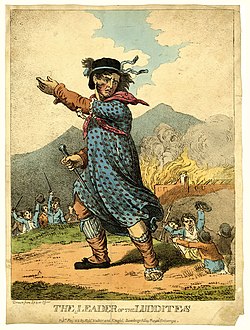

The image at the top of this page, the most famous of surviving depictions of Ludd, depicts him as a giant, leading the workers onward as a factory burns in the background. That Ludd is dressed in women's clothing is notable, as many of the groups of male Luddites dressed in drag when they went to destroy machinery and mill owners' mansions. Drag in this context was seen as an acknowledgement of the female laborers who were among the first to be displaced by machines during the Industrial Revolution.[3]:206-207

“”The Luddites swung hammers forged by a blacksmith named Enoch Taylor, who also made machinery for their adversaries, mill owners. "Enoch made them," the Luddites would say. "So Enoch shall break them."[6]

|

The Luddite's tool of choice became known as "Enoch's Hammer".[7]

Ned Ludd evolved into the quasi-mythical character "General" (or "King") Ludd, the leader of disaffected workers across England, a kind of Robin Hood of the Industrial Age. The British government responded to this militant activism by making industrial sabotage a capital crime, and many Luddites were sentenced to execution or penal transportation.

Modern use[edit]

“”We owe the Luddites a great deal, in fact, for resisting the onslaught of automated technology, the onset of the factory system, and the earliest iterations of unrestrained tech titanism and corporate exploitation. For refusing to ‘lie down and die’ as those in power expected them to.

|

| —Brian Merchant[9][3] |

The term is now commonly applied to those who object to industry and technology on environmentalist grounds, rather than economic self-interest. It can also be applied to ideologies which are perceived as opposing modernisation and scientific progress in a more general sense.

One hopes that those who use the internet as a medium to inveigh against technology are aware of the irony of doing so (q.v. anarcho-primitivists such as John Zerzan and Derrick Jensen, who regard dispensing their precepts to a wide audience as more important than pointless personal purity; sort of using technology in a way that will quicken its disappearance — a more extreme example was the Unabomber). Otherwise, they've likely fallen into the territory of absurdity.

It is also a common meme for paleoconservatives when they rail about the internet or other such nonsense.

Many transhumanists describe their critics as luddites.[10]

Today, Neo-Luddism![]() is a philosophy that resists modern technology. Hard green, anti-science movement, anarcho-primitivism, Labor unions, survivalism, anti-materialism, anti-globalization, neoreactionary, and hobbyist groups[11] and Low-Tech Magazine[12] often have this philosophy integrated into their worldview despite having clashing political views. Putin, surprisingly, has Luddite tendencies as he doesn't seem to use a smartphone, internet, or social media,[13] while Donald Trump does use social media, despite being technophobic himself.[14]

is a philosophy that resists modern technology. Hard green, anti-science movement, anarcho-primitivism, Labor unions, survivalism, anti-materialism, anti-globalization, neoreactionary, and hobbyist groups[11] and Low-Tech Magazine[12] often have this philosophy integrated into their worldview despite having clashing political views. Putin, surprisingly, has Luddite tendencies as he doesn't seem to use a smartphone, internet, or social media,[13] while Donald Trump does use social media, despite being technophobic himself.[14]

Luddite fallacy[edit]

The term Luddite was adopted by economists to refer to the false assumption that increasing the efficiency of production would inevitably lead to a long-term reduction in labour while holding production constant. Thus, jobless, the labourers would be forced back into serfdom and poverty. This is not what happened in Europe and North America during the Industrial Revolution. Instead, it would be more accurate to say that the labour force remained constant, and productivity increased accordingly (this was the basis for economic growth during industrialisation).

Increasing efficiency can indeed cause severe short-term hardship to displaced workers, particularly within a laissez-faire economic regime, as the Luddite movement attests. The effect of Industrial Revolution on textile production in Britain greatly increased cotton imports to Britain and had the direct consequence of directly increasing cotton plantation-based slavery and concomitant cruelty in the Southern United States.[3]:221-230

In a truly post-scarcity society, it could be argued that technological unemployment![]() would not be a problem, since large-scale economic automation could make human labour redundant, and humans would have effectively unlimited leisure time.[note 2] Thus, 20th-century economists such as John Maynard Keynes imagined a future in which working hours could be greatly reduced.[note 3] While working hours have been in decline since the late 1800s as productivity has risen,[19] that vision of the future has not yet come to pass. The trade-off between economic growth and allowing the population a large amount of leisure time has been a difficult one, and the optimal distribution of resources in society is a problem that is still far from being solved.

would not be a problem, since large-scale economic automation could make human labour redundant, and humans would have effectively unlimited leisure time.[note 2] Thus, 20th-century economists such as John Maynard Keynes imagined a future in which working hours could be greatly reduced.[note 3] While working hours have been in decline since the late 1800s as productivity has risen,[19] that vision of the future has not yet come to pass. The trade-off between economic growth and allowing the population a large amount of leisure time has been a difficult one, and the optimal distribution of resources in society is a problem that is still far from being solved.

This fallacy shares some common assumptions with the broken window fallacy, namely that the point of work is to create jobs for people to do, rather than make things that are useful. It's possible that this notion derives from the religious idea of work.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ "By Grabthar's hammer, by the suns of Warvan, you shall be avenged!"[8]

- ↑ This is the vision of the future described, for example, by Marshall Brain in Manna[15] and in by Rick Webb in The Economics of Star Trek: The Proto-Post Scarcity Economy[16][17]

- ↑

We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not yet have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come – namely, technological unemployment. This means unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour.

But this is only a temporary phase of maladjustment. All this means in the long run that humanity is solving its economic problem … For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich to-day, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter — to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us![18]

References[edit]

- ↑ Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall (2007) Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199259908.

- ↑ Turning Away From Technology: A New Vision for the 21st Century by Stephanie Mills (1997) Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0871569531. Foreword by Theodore Roszak.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech by Brian Merchant (2023) Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0316487740.

- ↑ "Notes toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto" - Chellis Glendinning (1990). Retrieved from The Anarchist Library.

- ↑ Cambridge Biographical Dictionary, edited by Magnus Magnusson (1990) Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521395186.

- ↑ Luddites: They raged against the machine and lost by Paul Wiseman (Jan. 25, 2013 12:14 AM EST) Associated Press (archived from April 13, 2015).

- ↑ Ben o' Bill's, the Luddite: A Yorkshire Tale by D. F. E. Sykes & Geo. Henry Walker (1898). Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton via The Gutenberg Project. "I say I didn’t handle Enoch much myself. We called the big sledge hammer that we battered the frames with, Enoch, after Mr. Taylor of Marsden."

- ↑ Galaxy Quest: Quotes IMDb.

- ↑ Robots aren’t really going to take our jobs. They’re going to do something much worse: In his new book, Los Angeles Times columnist Brian Merchant connects the 19th century weavers’ rebellion with today’s battles with Big Tech and AI. by Soleil Ho (Sep. 26, 2023) San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ The Trouble with "Transhumanism": Part Two By Dale Carrico (December 22, 2004) Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies (archived from July 5, 2011).

- ↑ Burn It All Down: A Guide To Neo-Luddism (January 29, 2015 at 7:00 am) Gizmodo International.

- ↑ Low-Tech Magazine

- ↑ Inside Putin’s Echo Chamber: What a silly set of lies about a doctored YouTube clip in the Oliver Stone documentary tells us about how Putin gets his information. by Karina Orlova (June 26, 2017) The American Interest.

- ↑ Donald Trump's complicated relationship with technology by Josh Dawsey (12/30/2016 01:10 PM EST) Politico.

- ↑ Manna – Two Views of Humanity’s Future – Chapter 1 Marshall Brain.

- ↑ The Economics of Star Trek: The Proto-Post Scarcity Economy by Rick Webb (Nov 6, 2013) Medium.

- ↑ The Economics of Star Trek: The Proto-Post Scarcity Economy by Rick Webb (2019) self-published. Revised edition. ISBN 1796668877.

- ↑ Economic possibilities for our grandchildren by John Maynard Keynes (1930). In: Essays in Persuasion (1963) W. W. Norton & Co. pp. 358-373.

- ↑ Working Hours by Charlie Giattino et al. (2020) Our World in Data.