Technocracy

| Oh no, they're talking about Politics |

| Theory |

| Practice |

| Philosophies |

| Terms |

| As usual |

| Country sections |

|

|

“”A businessman who was also a biologist and a sociologist would know, approximately, the right thing to do for humanity. But, outside the realm of business, these men are stupid. They know only business. They do not know mankind nor society, and yet they set themselves up as arbiters of the fates of the hungry millions and all the other millions thrown in… I charge the capitalist class with having mismanaged society. You have not answered. You have made no attempt to answer. Why? Is it because you have no answer?

|

| —Jack London's dystopian novel The Iron Heel (1908)[2] |

Technocracy is a form of government in which the decision-makers are selected based on their relevant expertise, with a preference for those with scientific/technical knowledge. The general idea is that said people would treat a nation's problems as a series of 'engineering challenges' for which they would use the scientific method to discover not only the optimal solution, but the optimal manner in which to achieve it — free of bias, ignorance, or vested interest. This could be considered a form of meritocracy if those technocrats selected were selected on their previous professional achievements (though this makes the assumption that the educational/scientific 'ladders' available won't be biased against certain groups, such as women or the poor).

Though clearly Technocracy (in its pure sense) has not been instituted in any nation of the globe yet, we all live in a partial 'technocratic world' because our lives are shaped by governments and large companies being guided and heavily run by people with a (broadly speaking) technocratic viewpoint. This has led to 'small state' conservatives such as James Burnham![]() to claim in books such as his 1941 The Managerial Revolution that the new masters of our world were the 'professional–managerial class' who had sidelined the previously dominant politicians, capitalists, and aristocrats.[3] Eighty-odd years later, one might quibble on how desirable this situation is and point out details on which he was proven incorrect, but Burnham's general argument holds true.

to claim in books such as his 1941 The Managerial Revolution that the new masters of our world were the 'professional–managerial class' who had sidelined the previously dominant politicians, capitalists, and aristocrats.[3] Eighty-odd years later, one might quibble on how desirable this situation is and point out details on which he was proven incorrect, but Burnham's general argument holds true.

As such, when 'professional–managerial' experts are put into political power, they are often described as technocrats. In democracies, this often happens if the nation's political class is judged as incapable or unwilling to govern, or is found to be unpalatable to either the public at large and/or foreign opinion — for example, 'caretaker governments' in parliamentary democracies or 'non-political' cabinets in situations where there is a political 'negative majority'[note 1] exists — for example, in Italy in 2022.[4][5]

Background[edit]

While the seeds of technocracy were sown during The Enlightenment, the first real shoots were in the final decades of the 19th century; a time where the 'Second Industrial Revolution'![]() was in full swing (giving several technological keystones of the modern world, such as industrial chemical production, mass production, electricity, and the internal combustion engine) coupled with a growing 'scientifically'-minded middle class to run the technologies (rather than a 'traditionally'-minded middle class, put through an educational system geared towards producing lawyers, clergymen, and clerks). People unsurprisingly held the view that a 'scientific mindset' could improve all spheres of human life. This (somewhat naïve) 'faith in the future' was a real paradigm shift for humanity — a genuine belief in progress on all fronts. People had good reasons for believing this; scientific management promised material prosperity for all, medical advances (such as germ theory and knowledge of nutrition) promised improved human health and longevity, while the myriad gizmo-inventors such as Thomas Edison held out a vision of a cleaner world full of labour-saving devices. However, as with any 'movement', some dross got mixed up with the pearls; the belief that Sigmund Freud was in the progress of 'unravelling the mysteries of the human mind' and laying the parts logically in front of us, spiritualism was considered a legitimate scientific study of the afterlife, and that Francis Galton's eugenics would 'improve the race' in a similar manner humans had done with domesticated animals, while the mostly sane campaigns by the clean living movement got hijacked by cranks and religious zealots.

was in full swing (giving several technological keystones of the modern world, such as industrial chemical production, mass production, electricity, and the internal combustion engine) coupled with a growing 'scientifically'-minded middle class to run the technologies (rather than a 'traditionally'-minded middle class, put through an educational system geared towards producing lawyers, clergymen, and clerks). People unsurprisingly held the view that a 'scientific mindset' could improve all spheres of human life. This (somewhat naïve) 'faith in the future' was a real paradigm shift for humanity — a genuine belief in progress on all fronts. People had good reasons for believing this; scientific management promised material prosperity for all, medical advances (such as germ theory and knowledge of nutrition) promised improved human health and longevity, while the myriad gizmo-inventors such as Thomas Edison held out a vision of a cleaner world full of labour-saving devices. However, as with any 'movement', some dross got mixed up with the pearls; the belief that Sigmund Freud was in the progress of 'unravelling the mysteries of the human mind' and laying the parts logically in front of us, spiritualism was considered a legitimate scientific study of the afterlife, and that Francis Galton's eugenics would 'improve the race' in a similar manner humans had done with domesticated animals, while the mostly sane campaigns by the clean living movement got hijacked by cranks and religious zealots.

Variants[edit]

In the century-plus since, several 'technocratic' movements have waxed and waned, with differing levels of success. As they often shared distinct overlaps, it was common for individuals to over time slide from one to another, as well as seeing 'merit' in the other variants — such as the works of H.G. Wells.![]() [6]

[6]

Efficiency Movement[edit]

The first variant of technocratic ideals; running between around 1890 to 1920 in many industrial nations, such as the UK ('National Efficiency' under the 'New Liberalism'[7] of David Lloyd George![]() ) and the USA ('Progressivism'[8] under Theodore Roosevelt). The Efficiency Movement's

) and the USA ('Progressivism'[8] under Theodore Roosevelt). The Efficiency Movement's![]() guiding principle was simple; that the state would actively intervene in the country's affairs, to drive modernisation, hack out inefficiencies and encourage best practice — if laissez-faire economics, tradition, or vested interests got in the way of this, then it was them who had to give way to logic and the needs of the nation. This was a break with the prevailing 'classical liberalism' of the latter Victorian era/Gilded Age (which by modern standards we would call libertarianism), but also broke with conservative 'paternalism' in which our 'efficient state' was motivated only by 'enlightened self-interest' — that it did not wish (for example) to improve the heath of the public because it was 'the right thing to do', but simply that healthier people were better workers who paid more taxes, were fit for military service if required, and were more likely to become good parents. If this sounds like 'master of the obvious' to you, it's because to a major extent, the adherents won the argument on the core concepts.

guiding principle was simple; that the state would actively intervene in the country's affairs, to drive modernisation, hack out inefficiencies and encourage best practice — if laissez-faire economics, tradition, or vested interests got in the way of this, then it was them who had to give way to logic and the needs of the nation. This was a break with the prevailing 'classical liberalism' of the latter Victorian era/Gilded Age (which by modern standards we would call libertarianism), but also broke with conservative 'paternalism' in which our 'efficient state' was motivated only by 'enlightened self-interest' — that it did not wish (for example) to improve the heath of the public because it was 'the right thing to do', but simply that healthier people were better workers who paid more taxes, were fit for military service if required, and were more likely to become good parents. If this sounds like 'master of the obvious' to you, it's because to a major extent, the adherents won the argument on the core concepts.

It's important to note that the vast majority of proponents were not 'socialist' or even left-wing in a modern sense; many were merely applying new methods to old goals — for example, the British were motivated by shoring up their empire against their German and (to a lesser extent) American rivals,[9] while the Americans were motivated by wanting an economic, scientific and governmental base to allow them to get the clout deserving of a 'Great Power'. This goal was seen elsewhere in the autocratic modernisers such as Sergei Witte![]() (Czarist Russia), and the 'Hundred Days Reforms'

(Czarist Russia), and the 'Hundred Days Reforms'![]() (Qing China); people who were mainly interested in material reforms, not societal.

(Qing China); people who were mainly interested in material reforms, not societal.

Typical reforms included the professionalisation of the civil service (hiring experts, using modern statistical methods), expansion of the education system (schools, universities, public libraries),[10] a new focus on public health (municipal sanatoria for the mentally ill and those with infectious disease, regulation of patent medicines),[11] changes to improve economic efficiency (trust-busting, foundation of labour exchanges, resource conservation),[12][13][14] and putting in protections against 'disasters' (banking regulations, occupational safety legislation, old age pensions).[15] The zenith of this movement was undoubtedly the First World War, where all the major powers tightened the screws on every facet of domestic activity in an attempt to leverage as many resources as possible for the industrialised 'total war' (rationing, economic nationalisations, and conscription),[16][17] while the last gasp was the granting of women's suffrage and in the USA, the arrival of Prohibition.

Perhaps the most lingering negative effect the movement had on general society was the ones related to eugenics; such as the forced sterilisations of 'undesirables',[18] kidnapping of children from parents pre-judged to be 'unfit' for modern society for enforced assimilation,[19] and the belief that an early application of IQ tests on children would allow them to be assayed correctly for their 'later station in life' (unsurprisingly, supporting racialism).[20]

Scientific socialism[edit]

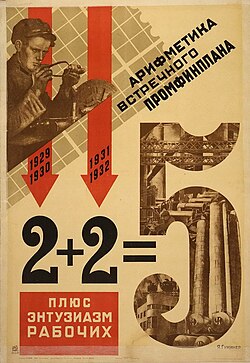

Scientific socialism could be glibly called 'Efficiency Movement as run by Marxists'. Revolutionaries such as Lenin took the experiences of the previous decades and of innovations such as 'scientific management'[21] — his theory was that if 'good Party comrades' were giving the directions rather than politicians 'in the pockets of capitalists', then the resources of the nation would be diverted into 'building communism' (which included enforced modernisation) rather than simply fattening foreign investors and their domestic hangers-on.

After a period in which the Soviets ran what is now call a mixed economy,[22] it was decided by Stalin amongst others that the pace had to be increased drastically. The result was the 'Five Year Plan';![]() the first attempt to scientifically plan an entire economy of a country in human history.[23][note 2] This created the command economy, which became the hallmark of the 'Second World',[note 3] which ran with little change until the collapse of the Soviet bloc in the late 1980s (surviving nominally-communist states such as China have shifted to a 'corporatist' method of organisation).

the first attempt to scientifically plan an entire economy of a country in human history.[23][note 2] This created the command economy, which became the hallmark of the 'Second World',[note 3] which ran with little change until the collapse of the Soviet bloc in the late 1980s (surviving nominally-communist states such as China have shifted to a 'corporatist' method of organisation).

Putting aside other discussions over the flaws of command economies, the main problem was that like their capitalist predecessors, the 'commissars' often ignored their experts, instead choosing options for political or selfish reasons instead (which produced ultimately worse solutions). Almost without fail, it soon became professionally or even personally dangerous for experts to demur from official policy, question leaders' 'pet projects', point out negative side-effects of previous policies, or suggest alternatives.[24] At least under capitalism, you were simply ignored and perhaps fired. Despite these issues, supporters of this system highlighted the determination and resource allocations it can grant to projects deemed 'of national importance' — for example, the construction of new industrial cities, hydroelectric dams, nuclear facilities, and Olympic stadia — yet often these were infected with 'gigantomania';![]() the desire to out-do competitors (normally the capitalist states) with sheer size when smaller, saner developments would have been more efficient in resource-use. Examples often cited as engineering 'white elephants' include Magnitogorsk

the desire to out-do competitors (normally the capitalist states) with sheer size when smaller, saner developments would have been more efficient in resource-use. Examples often cited as engineering 'white elephants' include Magnitogorsk![]() and Baikal-Amur Railway

and Baikal-Amur Railway![]() (Soviet Union), the 'Palace of the Parliament'

(Soviet Union), the 'Palace of the Parliament'![]() (Romania), and the Ryugyong 'Hotel'

(Romania), and the Ryugyong 'Hotel'![]() (North Korea).

(North Korea).

Technocracy Movement[edit]

Perhaps one of the most well-known political ideologies you probably haven't heard of; its forerunner was spotted in the immediate aftermath of the First World War,[note 4] but only came to the fore during the rapid onset of the Great Depression in (primarily) the United States and Canada — a time where the very underpinnings of capitalism and democracy appeared to be floundering.[25]

Having tried (and partly failed) to 'sufficiently' guide aristocrats, capitalists, politicians, or commissars into building a world of their liking and apparently unable to grasp onto what needed to be done to get out of the crisis, our budding technocrats began to organise, arguing that only they really had a viable plan and it would be best for all if they were simply allowed to get on with it without 'interference'. To top this off, they had their own logo (a ying/yang called 'The Monad'), a 'uniform' (grey suits and blue ties), a picked colour (if grey can be described as such), liked to greet each other by a salute, and eventually gave each other number-letter code names. If this is reminding you of something, you're not the first,[26] as early detractors called it 'an incipient fascist movement', and it splintered almost immediately when some key people fell out with the wannabe 'Continental Director', Howard Scott.![]()

What it wanted, in short, was an 'North American Union'[note 5] ruled by a self-selecting oligarchy of engineers and scientists, the turning of fiat currency into an energy-backed currency,[note 6] the rollout of universal basic income from the proceeds of the previous, and a firm goal to move towards a technological utopia for all.[27][28]

Ultimately, it was a true 'flash in the pan' movement, though it held on as a force in places like California and British Columbia into the 1950s. Its 'failure to launch' can be put down to (apart from the fascistic echoes) a fuzziness as to what a 'Technocratic' government's programme would be, no apparent plan on how they'd gain power to implement said programme, and lack of ability to persuade the wider public that the situation was bad enough to accept the jettisoning of democracy. There's a good chance that it only flared into the public consciousness due to there being a 'gap in the market' between the perceived inaction of Herbert Hoover and the coming corporatism of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal, which drained off all but the most ideologically committed Technocrats.[29]

Nearly a century later, only a few relics remain past the term itself; such as the 'Air Dictatorship' in HG Wells' 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come![]() (of which the latter chapters could be seen as a de facto 'Technocracy manifesto') and the 'World State' in Aldous Huxley's 1932 Brave New World (which is more a warning against at least a form of 'Technocratic society'[30]).

(of which the latter chapters could be seen as a de facto 'Technocracy manifesto') and the 'World State' in Aldous Huxley's 1932 Brave New World (which is more a warning against at least a form of 'Technocratic society'[30]).

Corporatism[edit]

Corporatism is both an old and new idea; this being that society was made up of different 'corporations', in a broad sense,[note 7] and that it was the duty of them to cooperate to find the ideal solution. Its modern variant arose in the late 19th century as a reaction/counterpoint to both Marxist socialism and laissez-faire capitalism, touted by (amongst other things) the Catholic Church in pronouncements such as the 1891 Rerum novarum,![]() something which pissed off both other opposing factions at the time[31] and continues to do so today.[32] One might have heard of this via its watered-down edition called 'stakeholder capitalism',[33] which the usual suspects hate like poison (National Review, Mises Institute).[34][35]

something which pissed off both other opposing factions at the time[31] and continues to do so today.[32] One might have heard of this via its watered-down edition called 'stakeholder capitalism',[33] which the usual suspects hate like poison (National Review, Mises Institute).[34][35]

Its modern form was first popularised by Benito Mussolini in the 1920s, with the principle of compulsion being added to the theory — to make permanent the various ad-hoc measures introduced during the First World War in the advanced economies and to spur growth and development greater than what free-market capitalism could achieve by themselves.[36][37][38] If communists wanted a 'command economy' and capitalists desired a 'market economy', corporatists proposed a 'directed economy' — where capital, labour, resources etc would be funnelled towards the optimum solutions. Despite this being popularised by a strongly authoritarian character such as Il Duce, corporatism is not inherently in conflict with either democracy or personal freedom in general (that is, unless one is a free-marketeer ideologue who considers any restrictions on one's ability to make money akin to slavery).

While variants started to be spotted in weaker/smaller nations who used it to harness limited resources to speed up modernisation (such as in Turkey under Kemal Ataturk[39]), corporatism really took off in the 1930s, as the laissez-faire world economy fell apart and threatened to drag down most of the independent states with it. Nations grew hugely more autarkic and interventionist; tariff walls, bank bailouts, the formation of state-backed business syndicates, the fixing of prices and wages, limits on the import/export of capital, and so on. An excellent example of this in a democratic state was the New Deal in the USA; showing that the main issue was not so much the concept itself, but more the goals to which it was put and the methods employed — that it did not have to be the 'going over roughshod over people's freedoms to build a war machine' à la Nazi Germany.

By the outbreak of the Second World War, the vast majority of the world's countries were under some form of corporatism (albeit to differing levels and styles), and after the conflict, it became the dominant form of government economic policy throughout the non-communist world until the rise of neoliberalism in the 1980s. Current systems such such as the Party-state capitalism![]() seen in China under Xi and Putinism in Russia are generally considered to be modern variants of corporatism.

seen in China under Xi and Putinism in Russia are generally considered to be modern variants of corporatism.

Current Trends[edit]

Not only do we continue to reside in a technocratic world heavily run by the 'professional–managerial' class, but its views continue to resonate and shape it further. Not only do all the previous iterations still have their proponents, we have seen in the last few decades the growth of what can be termed the 'Dark Technocracy'; people who — despite sharing their predecessors' firm belief in technology — don't subscribe to either Enlightenment values or the utopian dreams of most of their predecessors.[40] Instead, most circle around ideologies found within the neoreactionary movement; most commonly a form of neo-feudalism![]() where a technological-financial elite (which foolishly includes themselves[41]) enjoy almost unlimited power while the masses are either utterly disregarded or, if lucky, get some crumbs from their master's table if judged as 'useful servants'. While the majority of capital in this era is controlled by the fairly nondescript 'managers' outlined above at the behest of other managers with no goal apart from making more money, a significant portion of the 'active ultra-rich' are (at least in part) members of this movement.[42]

where a technological-financial elite (which foolishly includes themselves[41]) enjoy almost unlimited power while the masses are either utterly disregarded or, if lucky, get some crumbs from their master's table if judged as 'useful servants'. While the majority of capital in this era is controlled by the fairly nondescript 'managers' outlined above at the behest of other managers with no goal apart from making more money, a significant portion of the 'active ultra-rich' are (at least in part) members of this movement.[42]

Peter Thiel[43] has embraced transhumanism so he (and other chosen oligarchs) can live (and rule) forever,[44] Mark Zuckerberg tries to sell us a hyper-capitalised simulated reality[45][46] in lieu of the screwed-up one we currently inhabit while Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk plan to sidestep this issue with bullshit plans for colonising other worlds, instead[47][48][49] — or to watch this world collapse and then arise like gods from the ashes.[50] Energy tokens are back, except they're called Bitcoin (rather than just being pegged to energy production and use, they just waste energy)[51] and so many people assure us 'they're the future' for… reasons. Effective altruism will save the world by working out logically what would be the 'best' charity to give to, doubtlessly decided by AI using utilitarian criteria and mining big data — which will increasingly micromanage the neo-serfs' lives to the point that free will becomes more theoretical than actual. All ruled over by an elite who deserve to be there because of their obvious success, demanding that their views on everything is correct due to their ability to make lots of money and mocking the serfs for their 'lack of gumption' to bootstrap themselves into the elite class. In fact, some question whether the nation-state itself is a dead concept… or actively desire to make it so.[52][53][54]

If this sounds like a pastiche of the technological dystopias such as Cyberpunk 2077 and the Deus Ex series, that's because they come from the same source material. The amusingly sad thing is that many of our wannabe technocratic overlords[55] don't seem to realise that the world they're constructing is desired by almost nobody, or even that they are the villains of the tale — such as when Musk compared himself to the original Deus Ex protagonist JC Denton, but the public response was to compare him to the technocratic antagonist Bob Page instead.[56]

DOGE[edit]

Elon Musk and fellow plutocrat Vivek Ramaswamy announced a technocracy-style quasi-governmental crew of tech bros,[58][59][60] DOGE (the "Department of Government Efficiency"), with a bullshit announcement ("we’ll reverse a decades-long executive power grab") shortly after Trump's 2024 election.[61] Musk began implementing it almost immediately after Trump's inauguration, but not before Ramaswamy was quit-fired (because no one can stand close proximity to Musk for very long).[62] DOGE has caused widespread chaos across government departments, which is hardly a sign of efficiency.[63] There is also evidence that Musk is self-dealing with DOGE by knee-capping agencies that directly regulate or compete with his businesses, such as NASA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.[64][65]

It's no coincidence that DOGE was named after Musk's favorite cryptocurrency to pump-and-dump, the inflationary Dogecoin.[66]

Although claimed to be a government efficiency organization, there is good reason to believe that it just a cover for a kleptocratic and/or Kakistocratic organization:[67] cuts in budgets and staffing will likely cost far more than they save] by Zachary B. Wolf (May 30, 2025) CNN[68] many if not all of the "experts" that Musk selected came from his own companies and had no experience in government,[69] data theft by the DOGE employees is likely to benefit Musk's companies,[70][71] the evisceration of some government branches are likely to directly benefit Musk's companies (cutting the National Labor Relations Board harms private employee rights, cutting NASA benefits SpaceX, and cutting National Highway Traffic Safety Administration benefits Tesla).

Critique[edit]

Like any political-economic system, technocratic forms have both positive and negative elements, many of which have 'in the eye of the beholder' subjectiveness about it. The relative attractiveness of the system is dependent on circumstance; a nation facing an existential threat (such as a full-scale invasion or an economic collapse) may regard the negatives as being so minor in comparison that 'they're not worth talking about', but in a time of calm and plenty, the negatives become key issues for abandoning it.

Democracy[edit]

The most common complaint is that technocratic regimes are inherently anti-democratic; as in at least a portion of decisions are being made by manager-technocrats and not by politicians who have been elected by the people on a manifesto. Politicians of various political hues have long complained that 'the civil service'/'bureaucrats'/'officialdom' have either hamstrung or outright reject their goals — a tussle of wills between the power of the officials vs the authority of the politician (best illustrated for comedic effect by the classic BBC series Yes Minister)![]() - something which some people will describe (often in conspiratorial terms) as the existence of a 'deep state'. An even more common complaint is that the elected politician has responsibility but not power, while for the official, it's reversed — that unless the screw-up was catastrophic, the official's career will continue unmolested, but their political master will carry the can. In 'pure' technocratic regimes, the deficit is even worse, because there is no 'people's representative' within the organisation challenging assumptions, giving the general 'direction of movement', and looking out for the people's interest.

- something which some people will describe (often in conspiratorial terms) as the existence of a 'deep state'. An even more common complaint is that the elected politician has responsibility but not power, while for the official, it's reversed — that unless the screw-up was catastrophic, the official's career will continue unmolested, but their political master will carry the can. In 'pure' technocratic regimes, the deficit is even worse, because there is no 'people's representative' within the organisation challenging assumptions, giving the general 'direction of movement', and looking out for the people's interest.

Technocrats would argue that this was exactly the point: that by being elected, the politician does not gain any special insight to their constituents' needs or views, may have zero experience or knowledge of the decisions being put to them, and may well make the decisions based on factional interest and/or their own biases and/or selfish desires, while the technocrat would be able to make the best decision for all (meaning the thwarting of the politician's schemes was correct). What's more, it avoids the 'electoral cycle effect', in which democratic states find it difficult to tackle long-term problems because the costs are immediate but the benefits would be decades hence (and thus beyond the career span of the average politician, or simply the attention span of the average voter). What's more, democracy comes in many forms; while representative democracy and technocracy might be incompatible, it's possible to construct a hybrid system using other methods, including 'when needed' constituent assemblies![]() to tackle the big questions of the day, 'advisory panels' chosen by sortition to allow public oversight, or the use of referenda

to tackle the big questions of the day, 'advisory panels' chosen by sortition to allow public oversight, or the use of referenda![]() to 'cut out the middleman' and simply ask the people directly — thus allowing public participation in discussions and (ideally) 'buy-in' for the plans (though some technocrats have little to no truck for this, because they don't believe in the 'wisdom of the crowd' due to the power of demagogues and oligarch-fueled propaganda).

to 'cut out the middleman' and simply ask the people directly — thus allowing public participation in discussions and (ideally) 'buy-in' for the plans (though some technocrats have little to no truck for this, because they don't believe in the 'wisdom of the crowd' due to the power of demagogues and oligarch-fueled propaganda).

Lastly, they'll simply point out that our worlds and lives are dominated by entities which have almost no 'democratic' oversight — privately-owned corporations and finance houses. Odd, how so many right-wingers bleat about 'freedom' and 'democracy' but completely ignore the fact that these days most large private entities have way more power over the citizen than the state does, are only really accountable to their shareholders, and in many areas of our lives, effectively unavoidable.

Expertise[edit]

If you're promoting decision-makers on the basis of relevant expertise, you then start the argument on what that expertise looks like. Take, for example, a school — technocratic logic would suggest that a teacher should run it. But is their expertise relevant? A teacher knows about, well, teaching, not running an organisation. Unless by chance, they won't have experience in dealing with budgeting, staffing, legal compliance, or planning maintenance schedules. In fact, some technocrats would argue that a professional manager is in fact the person with the 'relevant expertise'. There is also the spectre of the Peter Principle and of opportunity cost to consider; it may in fact be a suboptimal decision to turn a brilliant teacher into a mediocre administrator, the best way for that teacher to contribute being to continue teaching (but this does mean they've fallen into the 'too valuable to promote' trap which bedevils many organisations). In fact, some folks might prefer this because (for example) our teacher's passion is teaching, not administration.

The next issue with 'relevant expertise' is when dealing with similar, but distinctly different fields. For example, an experienced banker is unlikely to have a huge amount of insight on how to organise a industrial strategy — for the banker is an expert in finance while the expertise being asked for comes from economics. Even sub-fields of a discipline might not be 'relevant'; for example, a data-driven classical economist being tasked to draw up a programme to eliminate poverty.[note 8]

Most important is the limits of expertise. Said expert's knowledge/experience may be significantly out of date (often a risk if they'd been promoted into administration aeons ago) and/or may be in a field where there is no firm scientific consensus to rely on (for example, in most social sciences). Variants of Nobel disease are also an issue; seniors pushing their own pet theories and using their status to stifle criticism on it from more junior peers. Last but not least, an expert might not be capable of communicating in a manner which people outside of their discipline actually understand — after all, 'science communication' is a skillset in their own right (which an expert may not possess).

Goals[edit]

'Evidence-based policy making' is all well and good, but there's questions that simply can't be answered using this method, most obviously relating to goals — it might be able to show us the best methods of teaching and the most effective materials, but it won't show us the best curriculum that the schools should follow. Somebody, somewhere will need to tell us 'what is education meant to achieve?', and only then can our experts tell us how best this can be achieved.

This 'somebody' would not only have to grapple with this question, but also be bombarded from many quarters what they believe the answer is. For example, business will advocate for more 'practical workplace training', the military pushes for more physical education to deepen their future conscription pool, while sociologists argue the key is to drastically increase the civics component to help to inoculate the youth in how they can be a productive, aware citizen. Clearly, not everyone's desires can be accommodated — decisions must be made, and once they have been, must be sold to both the 'losing' interest groups and the wider public that this is the correct course of action.

Technocrats try to answer this by arguing that a technocratic society could provide such persons — such as utilising professional judges (and their analytical reasoning skills) or even entrusting said decisions to an artificial intelligence. But this simply sidesteps the issue — judges and AIs alike are given guidance on what elements are the most important, requiring somebody to ask what said guidance should say.

Mismanagement[edit]

Technocrats are human beings like the rest of us, and thus fallible. From political biases to naked self-interest, there are several ways where our technocrat's 'objective' decision is, in fact, rather partisan — for example, favouring policies that benefit their own department or themselves personally over the wider needs of the public. Corruption, collusion, cronyism, rent-seeking behaviour, and similar can grow very quickly in a technocratic system if not checked; even the most benign 'careerism' can reduce efficiency if doing the 'right' thing required taking actions which would damage the individuals' future career prospects (which is often cited against allowing monopoly power in any sector; that if someone falls out with the established hierarchy, they are capable of leaving and continuing their career elsewhere).

More malign is the problem of a faulty application of Occam's Razor; the technocrats may select the easiest solution, rather than the correct one. Examples of this can include 'shooting the messenger' (you 'solve' the problem by silencing the person reporting it), 'moving the goalposts' (retconning past goals to fit current reality so you've succeeded in meeting them), deploying propaganda and engaging in psychological manipulation (to convince the public that the group's goals are in fact theirs and/or 'there is no alternative' to their plan), and engaging in tokenistic or performative actions (to reassure the public that something is being done, much as with security theatre).

Technocracy supporters would retort that all of these are that which can and often are spotted in all forms of organisation; that the majority of private companies aren't run on technocratic principles but still show these symptoms. That often the problem lies in these organisations being opaque to the general public and said public getting insufficient civics lessons or access to investigative journalism to realise the scams. Ultimately, much of the complaints are of a 'perfect is the enemy of good' type — that because they can't propose a way to eliminate all of the issues, their proposal is not worth discussing.

External links[edit]

- What's wrong with Technocracy? Boston Review 'Longread'

Notes[edit]

- ↑ When politicians can only agree on what they won't support, not what they will. Thus, there is political paralysis.

- ↑ A more impressive feat when you consider the fact that the State Planning Committee (Gosplan) had zero computing power, experience, or even methodology to accomplish this, and that the Soviet Union was the largest nation by land area.

- ↑ The 'First' being the advanced capitalist nations and the 'Third' the poorer non-aligned nations.

- ↑ The small 'Technical Alliance' group first met in 1919, while the term 'Technocracy' was also coined this year, but by one Smyth who had nothing to do with the later movement.

- ↑ Called the 'Technate of North America'.

- ↑ This wasn't as nuts as it first looks, as the world had just abandoned the gold standard; hell, energy is a slightly more logical thing to measure 'value' with, as everything has 'energy inputs' into it, but not much so much for a shiny yellow metal.

- ↑ In this case meaning 'common interest groups'. So yes, private companies are 'corporations', but so are religious groups, trade unions, local communities, etc.

- ↑ They will most likely argue that sorting out poverty requires increasing the general income level of the country and then 'poverty will simply vanish' due to trickle-down economics.

References[edit]

- ↑ Monti unveils technocratic cabinet for Italy (16 November 2011) BBC News..

- ↑ The Iron Heel, via Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ The Managerial Revolution by James Burnham (1962 [1941) Penguin Books

- ↑ Italy's technocratic anomaly: The country needs to develop a new, wiser political culture that seeks to stabilize its politics. by Tommaso Grossi & Francesco De Angelis (25 July 2022) Politico.

- ↑ So what exactly is a technocrat anyway? What is a ‘technocrat’? And why are technocratic governments all the rage these days in Europe? by Joshua A Tucker (16 November 2011) Al Jazeera.

- ↑ The Scientific Socialism of H. G. Wells by Joshua Fagan (3 July 2023) Jacobin.

- ↑ The New Liberalism by Duncan Brack, Journal of Liberal History.

- ↑ How Gilded Age Corruption Led to the Progressive Era by Christopher Klein (4 February 2021) History Channel.

- ↑ The Fitzroy Report, 1904: How the poor physical condition of Boer War army recruits prompted social change by Fiona McCall (30 April 2021) University of Portsmouth's History Blog.

- ↑ America at School Library of Congress.

- ↑ TB in America: 1895-1954 PBS American Experience.

- ↑ This Day In Politics: Theodore Roosevelt assails monopolies, Dec. 3, 1901 by Andrew Glass (3 December 2018) Politico.

- ↑ Winston Churchill, Forgotten Progressive? by Eamonn Bellin (7 October 2022) American Purpose.

- ↑ Theodore Roosevelt and the Environment PBS American Experience.

- ↑ Old Age Pensions Act Spartacus International.

- ↑ How War Amplified Federal Power in the Twentieth Century by Robert Higgs (July 1, 1999) Foundation for Economic Education.

- ↑ Total War by Jennifer Llewellyn et al. (2014) Alpha History.

- ↑ The Supreme Court Ruling That Led To 70,000 Forced Sterilizations (7 March 2016) NPR Healthshot.

- ↑ A century of trauma at U.S. boarding schools for Native American children by Erin Blakemore (9 July 2021) National Geographic.

- ↑ Racism and Intelligence Test Scores (14 March 2016) Facing History.

- ↑ The Taylor System - Man’s Enslavement by the Machine by V. I. Lennin (2004) Marxists Internet Archive. Originally published in Put Pravdy No. 35, March 13, 1914

- ↑ The New Economic Policy (NEP) by Steve Thompson et al. (February 22, 2024) Alpha History.

- ↑ Five-Year Plan by Darren G. Lilleker (May 11 2018) Encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Shakhty Trial by John Simkin (2020) Spartacus Educational.

- ↑ Science: Technocracy’s Week (23 January 1933) Time.

- ↑ Technocracy: A Totalitarian Fantasy: Myths and Realities About a "New Order" Marxists Internet Archive. Originally published in: New International, Vol. X No. 3, March 1944, pp. 73–78.

- ↑ The Last Utopians by Ray Argyle (1 January 2018) Canada's History.

- ↑ Technocracy, Inc. and the Technate of America Boston Rare Maps.

- ↑ A non-conforming technocratic dream: Howard Scott’s technocracy movement. 3. The rise and fall of Howard Scott’s technocracy movement by Kyunghwan Oh (2024) Management & Organizational History 19(2), 108–123. doi:10.1080/17449359.2024.2343657.

- ↑ Brave New World at 75 by Caitrin Keiper (Spring 2007) The New Atlantis.

- ↑ Is Rerum Novarum a Socialist Manifesto? by Michael D. Greaney (September 25, 2022) Catholic World Report.

- ↑ Can a Catholic Be a Capitalist? by Trent Horn (18 Feburary 2020) Catholic Answers.

- ↑ What Is Stakeholder Capitalism? by Deborah D'Souza (October 03, 2022) Investopedia.

- ↑ ‘Stakeholder capitalism’ is corporatism in disguise by Andrew Stuttaford (July 9, 2020 6:30 AM) National Review (archived from 9 Jul 2020 12:28:01 UTC).

- ↑ The Problem with "Stakeholder Capitalism" by Frank Shostak (6 November 2021) Mises Institute.

- ↑ Fascist Italy's Experiment With Economic Corporatism by Philip Scranton (15 July 2013) Bloomberg (archived from 25 Sep 2023 15:38:27 UTC).

- ↑ Mussolini on the Corporate State by Chip Berlet (12 January 2005) Political Research Associates.

- ↑ Economic Fascism by Thomas J. DiLorenzo (1 June 1994) Foundation for Economic Education.

- ↑ Atatürk's Understanding of Statism by Hasan Yuksel, Who Is Atatürk.

- ↑ The Rise of Techno-authoritarianism: Silicon Valley has its own ascendant political ideology. It’s past time we call it what it is. by Adrienne LaFrance (30 January 2024) The Atlantic.

- ↑ Original Position Fallacy TV Tropes.

- ↑ How Musk, Thiel, Zuckerberg, and Andreessen—Four Billionaire Techno-Oligarchs—Are Creating an Alternate, Autocratic Reality by Jonathan Taplin (22 August 2023)Vanity Fair.

- ↑ The Contrarian review - inside the strange world of PayPal founder Peter Thiel by John Naughton (3 October 2021) The Observer.

- ↑ The first men to conquer death will create a new social order – a terrifying one The New Statesman, 25 August 2017.

- ↑ The Metaverse is the internet no one wants by Thomas Claburn (14 October 2022) The Register.

- ↑ Mark Zuckerberg’s “Metaverse” Is a Dystopian Nightmare by Ryan Zickgraf (25 September 2021) Jacobin.

- ↑ Why is Bezos flying to space? Because billionaires think Earth is a sinking ship by Hamilton Nolan (20 July 2021) The Guardian.

- ↑ Elon Musk Has a New Excuse for Not Making It to Mars: The billionaire says that if he doesn't successfully colonize Mars at some point in the next few years, you can blame Kamala Harris. by Lucas Ropek (September 11, 2024) Gizmodo. "Musk, a studied peddler of vaporware, is used to spouting off bullshit that uninformed stans think sounds cool, only to then never accomplish the feat he claimed he would accomplish."

- ↑ Elon Musk: Mars rocket will fly 'short flights' next year by Jackie Wattles (March 11, 2018: 4:13 PM ET) CNN Business.

- ↑ The Apocalyptic Delusions of the Silicon Valley Elite by Douglas Rushkoff (16 February 2023) Current Affairs.

- ↑ 100 years ago, Henry Ford proposed ‘energy currency’ to replace gold by Sam Bourgi (18 September 2021) Cointelegraph.

- ↑ The crypto bros who dream of crowdfunding a new country by Gabriel Gatehouse (20 September 2024) BBC.

- ↑ Inside tech billionaires’ push to reshape San Francisco politics: ‘a hostile takeover’ by Ali Winston (12 February 2024) The Guardian.

- ↑ The Tech Baron Seeking to Purge San Francisco of "Blues" by Gil Duran (26 April 2024) The New Republic.

- ↑ In science we trust by Ira Basen (28 June 2021) CBC News.

- ↑ Elon Musk Compares Himself to Deus Ex Hero, Fans Think He's More Like the Villain by Callum Williams (2 May 2020) GameRant.

- ↑ 11 Warning Signs Your Logo Sucks by Samantha P (2023) LogoMakr. "3. Your logo looks generic." "6. You can’t explain what it means…" "7. It doesn’t fit with what people are expecting from your brand."

- ↑ As errors pile up, Musk and DOGE appear increasingly incompetent by Steve Benen (Feb. 19, 2025) MSNBC.

- ↑ Here Are All the Tech Bros Helping Elon Musk Gut the Government by Edith Olmsted (January 13, 2025) The New Republic.

- ↑ 21 tech staffers quit from DOGE en masse, warning Elon Musk’s hires are political ideologues without the necessary skills or experience by Brian Slodysko et al. (February 25, 2025 at 9:26 AM PST) Fortune.

- ↑ Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy: The DOGE Plan to Reform Government: Following the Supreme Court’s guidance, we’ll reverse a decadeslong executive power grab. by Elon Musk & Vivek Ramaswamy (Nov. 20, 2024 12:33 pm ET

- ↑ Vivek Ramaswamy Wasn’t ‘Radical’ Enough for DOGE Head Musk: Just hours after Trump’s inauguration, Ramaswamy quit the “cost-cutting” task force to run for governor of Ohio. by Janna Brancolini (Feb. 28 2025 11:59AM EST) Daily Beast.

- ↑ Alsobrooks, Warren, Smith Question HUD Secretary on Alarming Consequences of New DOGE Task Force on Housing for Americans (February 24, 2025) United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs.

- ↑ The agency that regulates vehicle safety — and Elon Musk's Tesla — is another target of DOGE layoffs by Feb 24, 2025, 7:40 AM PT) Business Insider.

- ↑ How DOGE Has Affected NASA So Far by Alyssa Lafleur (February 28, 2025) Space Insider.

- ↑ Elon Musk Dogecoin pump incoming? SOL tipped to hit $300 in 2025: Trade Secrets. Crypto analysts share their tips on a potential Musk-fueled Dogecoin price rally, plus Bitcoin, Solana and other coins. by Ciaran Lyons (June 10, 2025) Cointelegraph Magazine.

- ↑ Kleptocracy, Inc. Under Trump, conflicts of interest are just part of the system. by Anne Applebaum (April 14, 2025) The Atlantic.

- ↑ Scorecard: How Musk and DOGE could end up costing more than they save

- ↑ The DOGE 100: Musk Is Out, but More Than 100 of His Followers Remain to Implement Trump’s Blueprint by William Turton et al. (June 10, 2025, 3 p.m. EDT) ProPublica.

- ↑ A whistleblower's disclosure details how DOGE may have taken sensitive labor data by Jenna McLaughlin (April 15, 20255:00 AM ET) NPR.

- ↑ Report reveals how Musk and DOGE could profit from access to personal data and federal contracts—and potentially cost working people billions of dollars (May 7, 2025) Economic Policy Institute.