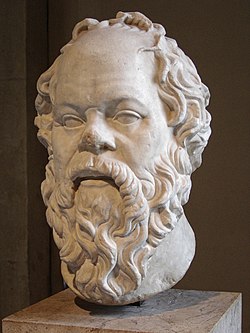

Socrates

| Thinking hardly or hardly thinking? Philosophy |

| Major trains of thought |

| The good, the bad, and the brain fart |

| Come to think of it |

“”I drank WHAT?!?!

|

| —Socrates |

Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, Socrates[notes 1] (470/469 - 399 BCE) was an enigmatic figure known only through other people's accounts. Plato's dialogues that have largely created today's impression of him, though others are credited with the impression that he was "a lovely little thinker, but a bugger when he's pissed."[notes 2] Prior to Socrates, presocratic philosophers expressed themselves in opaque verse and drama. Socrates is generally credited for introducing to Western thought a new method of imparting enlightenment; through a dialog, where points and counter-points are presented, with the truth (or, what Socrates believed to be the truth) finally becoming self-apparent through deduction. The scientific method has roots in the Socratic method.

Biography[edit]

Socrates was a soldier in his youth, but he spent most of his life as something of an indigent professor. Unlike other teachers (a common profession in Athens at the time) Socrates never took payment for his services. He was also known to dress in rags, go about barefooted and sleep outdoors. When not teaching, Socrates would spend his time engaging in debate with young men and merchants in the Athens city-center, or agora. Socrates took on several disciples, most famously Plato, who also became the primary source for information on the historical Socrates.

At age 70/71 — quite old by Ancient Greek standards — Socrates was sentenced to death by the Athenian council on the charge of "corrupting the youth of Athens", a.k.a. for asserting that the Greek myths were not literally true. (Insititutional murder has a long history as a means of ridding The State of dissidents - and proved especially useful to the powers that be before the invention of psych wards.) Other possible (covert) motives for his sentence were his frequent praise of Athenian rival Sparta, his open criticism of democracy, and his association with Critias and Alcibiades (the former was a leader of the pro-Spartan "Thirty Tyrants" installed after Athens' defeat in the Peloponnesian War, who were notorious for killing 5% of the Athenian population - among other oppressive acts; the latter was a skilled but polarizing general accused of blasphemy who defected first to Sparta and then to Persia to avoid the many enemies he had made throughout his political career). Socrates himself believed in an autocracy modeled on Sparta as the ideal form of government.[notes 3] Socrates remained defiant during his trial and when found guilty, was asked to propose his own punishment in place of the death-sentence proposed by the court; Socrates stated that he should receive a salary from the government and free meals for the rest of his life, in payment for his services to the city. Plato and Xenophon agree that Socrates had the opportunity to easily escape death, although his true reasons for refusing are less clear, especially when considering the possible agendas and biases of the two sources' interpretations.[1][2]

The Socratic method[edit]

The Socratic method (sometimes called Socratic irony) is a type of pedagogy in which a series of questions are asked, not only to draw individual answers, but to encourage fundamental insight into the issue at hand.

The Socratic Method can be also used as a rhetorical strategy. Employed fairly, it enables participants and observers of a debate to fully understand each side's position or at least be on the same page as to what the conversation's about.

Used in the service of bullshit (a Socraptic Method, as it were), one side keeps asking questions about definitions and other individual parts of their opponent's response until the target misspeaks or establishes an internal inconsistency (real or apparent) and then the would-be Socrates smugly points it out.

A classic example of a Socratic dialogue is Euthyphro. Socrates runs into Euthyphro, a well-thought-of theologian, on the way to market and the following (paraphrased) conversation ensues:

SOCRATES: Hey Euthyphro, what's holiness?

EUTHYPHRO: The holy is that which the gods love.

SOCRATES: But we live in friggin' ancient Greece, Euthyphro. We have a whole pantheon of gods and none of them can agree on anything - they argue with each other all the damn time, and tend to turn innocent humans into animals for no good reason. There's stuff which Zeus loves and Hera hates, so it'd have to be both holy and unholy, which is crazy, therefore you're a moron.

EUTHYPHRO: Why, yes, Socrates! You've revealed me for the fool I am!

SOCRATES: Q.E.D., bitches.

The Socratic problem[edit]

Socrates does not have any known writings, as he distrusted the written word. Our knowledge of the historical Socrates and his philosophy comes solely from three (sometimes contradictory) secondary sources: playwright Aristophanes, historian Xenophon and the philosopher Plato. Aristophanes was roughly the same age as Socrates, and they likely met multiple times amongst Athens' educated circles while in their 40s. His disciples, Xenophon and Plato, were about 45 years younger, and knew Socrates at the end of his life (app. 60 until his death).

Aristophanes' account primarily appears in the play, Clouds, where Socrates is presented as something of a comedic villain and corrupter of youth. Socrates teaches young men how to escape debts and control their parents as well as publicly mocks the gods' divinity and flouts Athenian tradition. Xenophon presents him as a man who was practical above all else and stated "I was never acquainted with anyone who took greater care to find out what each of his companions knew". Xenophon's rather pragmatic Socrates is pedestrian and unrevolutionary, which may be attributed to Xenophon not being a philosopher and therefore not fully understanding the Socratic philosophy and method. Bertrand Russell considered Xenophon to be rather stupid.[3] The most well known and extensive account is that of Plato. Plato's Socrates is the great philosopher; one who questioned everything, had no concern for conventions, and contempt for the settled beliefs of others. Despite the lack of additional historical evidence, historians generally agree that Socrates was a real person and well-known in 5th century B.C.E. Athens. All three sources agree that Socrates was profoundly ugly and rarely, if ever, bathed. This, in fact, may be the only thing modern historians can be certain about the real Socrates.[4][notes 4]

This presents a problem. Who was Socrates and what was his philosophy? The lack of primary sources and the distorted lens of history makes it nearly impossible to know where Socrates ends and his interlocutors begin. It is sometimes suggested that Plato's Socrates is little more than a cipher and means to add legitimacy to his own philosophy.[5] Regardless of the veracity of Plato's recounting of Socrates' philosophy, scholars believe Plato's biographical account to be the most accurate, as Plato knew him personally the longest. While the historian Xenophon would seem the most objective, the recording of history has changed significantly over the past two-and-a-half millennia. During antiquity, there was little distinction made between recording actual events and speculative events that could/should have happened together as "history". Similarly, Homeric and Heraclean mythology, along with tales of the Greek pantheon, were regarded as true history.[notes 5][notes 6] Modern historians believe that Xenophon often embellished (or out-right invented) events, including some of those associated with Socrates. Finally, Aristophanes' account primarily came in the form of an unflattering dramatization, which may have been a composite character representing Aristophanes' views on academia of the day. This, along with his other accounts, portray a man Aristophanes did not personally like. In fact, Plato recounts that Socrates specifically blamed his depiction in the plays for contributing to his judgement and death sentence. The historicity![]() of Socrates has been debated for centuries, and there are still no conclusions. Philosophers tend to sidestep the problem and consider it a historical question, and not of philosophical importance.[6]

of Socrates has been debated for centuries, and there are still no conclusions. Philosophers tend to sidestep the problem and consider it a historical question, and not of philosophical importance.[6]

Sayings[edit]

Because no works of Socrates survive (if he wrote any to begin with), sayings attributed to him should always be considered as apocryphal.

- "Know thyself."[notes 7]

- "All I know is that I know nothing."

- "Beware the barrenness of a busy life."

- "False words are not only evil in themselves, but they infect the soul with evil."

- "From the deepest desires often come the deadliest hate."

- "For let me tell you, gentlemen, that to be afraid of death is only another form of thinking one is wise when one is not; it is to think that one knows what one does not know."

See also[edit]

- Aristotle: Plato's disciple and tutor of Alexander the Great

- Evidence for the historical existence of Jesus Christ: The uncertain historicity of Jesus mirrors that of Socrates.

External links[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Not the Brazilian soccer player.

- ↑ See the "Philosopher's Drinking Song"

- ↑ At least according to Plato, in his Republic.

- ↑ Socrates', shall we say, rustic lifestyle may have arisen from the contemporary "Laconic

" fad, or basically being a weaboo for all things Sparta. Socrates' praise of Sparta may have motivated his arrest.

" fad, or basically being a weaboo for all things Sparta. Socrates' praise of Sparta may have motivated his arrest.

- ↑ Some things never change.

- ↑ Socrates' own forced suicide for questioning the gods' divinity is an example of how entrenched this belief in myth as history was in ancient Greek society

- ↑ Some suspect he was describing Plato's social life.

References[edit]

- ↑ http://www.philosophypages.com/ph/socr.htm

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Apology (Xenophon).

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand (1945) The History of Western Philosophy. Simon & Shuster pp.82-83

- ↑ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/socrates/

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Pseudepigrapha.

- ↑ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/socrates/#SocProWhoWasSocRea