Crusades

| Christ died for our articles about Christianity |

| Schismatics |

| Devil's in the details |

“”Kill them all. God will know his own.

| ||

| —attributed to abbot Arnaud Amaury |

“”The most signal and most durable monument of human folly that has yet appeared in any age or nation.

|

| —David Hume, 1778[2] |

The Crusades were a series of medieval-era military expeditions sanctioned by the Catholic Church to conquer religiously significant territories in the Eastern Mediterranean. Yes, the followers of so-called "religions of peace" openly stated that they would kill millions to keep the Holy Land in the hands of their religion.

They might have been considered solely a response to Islam's four-hundred years of unbridled expansion had the crusaders limited their targets to Muslim-held Spain and the fallen areas of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. However, they didn't do that. Instead, the crusaders attacked not only Muslims, but also heterodox Christians (known as Cathars) in southern France,[3] pagans in the Baltic region,[4][5] and even the Eastern Orthodox Christians of the Mongol-battered Russian states and the Eastern Roman Empire.[6] That last one is especially hilarious because the papacy started the Crusades in the first place due to the Eastern Roman Emperor's request for aid against the expansionist Seljuk Turks, who had whooped Byzantine ass at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.[7]

Central to the Crusades was the unfathomably bad idea of the Pope declaring that God would forgive all sins committed by the Crusaders,[8] leading to the campaigns being incredibly brutal even by the standards of the time. This also led to some very unpleasant experiences for the Jews, with the slaughter of thousands - mostly by the Christian side.[9]

After all of that bullshit, the Crusades in the Middle East were a miserable failure. Although the First Crusade succeeded in capturing Jerusalem and turning the "Holy Land" into Frankish colonial outposts, the crusaders were unable to hold onto it through the subsequent military campaigns. Israel/Palestine has been held by non-Christians ever since. While the Baltic and Cathar crusades succeeded in sword-point Christianizing (or, at least, efficiently slaughtering) their respective targets, the Fourth Crusade ended with the near-destruction of the Eastern Roman Empire, a trauma from which it would never recover, leading to its demise at the hands of the Ottomans.[6]

The Crusades[edit]

Crusades for the Holy Land[edit]

The First Crusade and the People's Crusade (1095-1099)[edit]

“”It was impossible to look upon the vast numbers of the slain without horror; everywhere lay fragments of human bodies, and the very ground was covered with the blood of the slain. It was not alone the spectacle of headless bodies and mutilated limbs strewn in all directions that roused horror in all who looked upon them. Still more dreadful was it to gaze upon the victors themselves, dripping with blood from head to foot, an ominous sight which brought terror to all who met them. It is reported that within the Temple enclosure alone about ten thousand infidels perished, in addition to those who lay slain everywhere throughout the city in the streets and squares, the number of whom was estimated as no less.

|

| —Archbishop William of Tyre on the massacre of Muslims in Jerusalem.[10] |

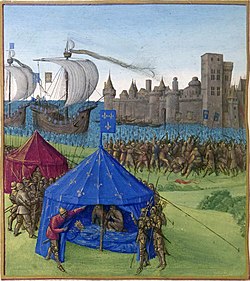

From 1067 onwards the Byzantine Empire suffered a long string of defeats at the hands of the invading Muslim Seljuk Turks and lost great swathes of territory,[11] culminating in the devastating Byzantine loss of the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.[12] The Eastern-Orthodox Byzantine Emperor, panicking for a few years, went to Pope Urban II asking for help from his Catholic half-brothers.[13] The pope, for his part, responded by delivering a sermon calling for a divinely-sanctioned war of conquest to Christian holy sites in the Levant and promising absolution from sin, land, and wealth.[14] A great number of Christians responded, and an army of 60,000 crusaders marched through Anatolia to invade the Levant.[15]

Before the crusading armies of knights and squires and hangers-on reached the holy land, however, a bunch of peasants gave it a try first. This occurred when a charismatic man named Peter the Hermit took inspiration from the pope and preached to European commoners calling for a general rising against the Muslims. Because of this, a massive peasant "army" marched towards Eastern Europe, sacking cities along the way and butchering entire Jewish communities.[16] Not surprisingly, the poorly-disciplined peasant army managed to sack exactly one Muslim-held city before the Turks crushed it completely. Thus ended the "People's Crusade".[16] It was stupid.

Eventually, the more prepared army led by "professional" knights arrived, and they too invaded the Levant. They saw more success than the People's Crusade, managing to take fortresses along the Mediterranean and in Mesopotamia. Finally, after a five-week siege, they took Jerusalem itself and killed all of the Muslims in it.[14] They also killed a lot of Jews, setting fire to the chief synagogue where many were sheltering.[17]

In a coda to the People's Crusade, one of the most feared and crazy groups of crusaders at the siege of Jerusalem was the Tafurs, a band of poor, ill-equipped men, led by a mysterious King Tafur, possibly a former Norman knight but claiming to be a spiritual leader.[18] They took oaths of poverty (although that didn't stop them looting), wore sackcloth rather than armour, wielded farm implements rather than swords, and were fond of rape and massacre of civilians, but particularly notorious for cannibalism; it is said by reputable historians who remain nameless that even the other Crusaders considered them uncontrollable. They became the subject both of tales of horror and (largely fictitious) narratives of religious heroism that claimed they were ordained by God.[19]

Intending to defend their new conquests, the Crusaders built castles and established a number of feudal monarchies which became known as the "Crusader states".[20] The Byzantines also got a bunch of their land back, but the devastation caused by the Crusaders in their territory pissed them off and permanently poisoned relations between the two sides of medieval Christianity (although ironically a major reason for the Pope to launch the crusade involved his intention of re-asserting control over the Eastern church).[15] This would have very bad consequences down the road.

The Second Crusade (1147-1149)[edit]

Unfortunately for the Crusaders, one of their shiny new kingdoms, the County of Edessa, fell to the Muslims in 1144.[21] This was the spark that led to the Second Crusade, as Christians in the region realized they were all under threat. Pope Eugenius III called for a new Crusade, but left the actual military goals of that Crusade fairly ambiguous.[22] This Crusade was already off to a bad start.

Despite travelling with the king of France and the Holy Roman Emperor, the Crusaders very quickly began running out of money, even before they reached the Middle East.[23] Matters became worse when they arrived in Anatolia to find that the Byzantine Empire was now much less welcoming than the first time around; sour relations between them sparked an actual battle and forced the Crusaders to hurry along into the Levant much faster than they'd intended.[24] The Crusaders arrived in Edessa to find the city deserted; the Turks had crushed a rebellion there so harshly that the entire city had been razed.[23]

Needing a new target, the Crusaders decided to go after Damascus instead. Stupidly, they hadn't considered the logistical requirements of marching through arid territory, and began running out of food and water.[22] The siege of Damascus predictably failed in a very short time, and the Second Crusade fizzled out like a wet firework.[22] Maybe God was napping during this one.

The Third Crusade (1187-1192)[edit]

Saladin![]() now enters the picture, and he was by all accounts a brilliant leader who managed to unite the Muslim powers and retake Jerusalem in the Battle of Hattin.[25] However, Saladin did allow the Christian residents of the city to flee rather than simply slaughter them outright[26] as the Crusaders had done to Jerusalem's unfortunate Muslims during the First Crusade.[27][28][29] Although this was pretty nice by the era's standards, it's still the Twelfth Century we're talking about, so Saladin went on ahead and demanded a ransom for that privilege and sold the stragglers into slavery.[30] So it goes.

now enters the picture, and he was by all accounts a brilliant leader who managed to unite the Muslim powers and retake Jerusalem in the Battle of Hattin.[25] However, Saladin did allow the Christian residents of the city to flee rather than simply slaughter them outright[26] as the Crusaders had done to Jerusalem's unfortunate Muslims during the First Crusade.[27][28][29] Although this was pretty nice by the era's standards, it's still the Twelfth Century we're talking about, so Saladin went on ahead and demanded a ransom for that privilege and sold the stragglers into slavery.[30] So it goes.

The fall of Jerusalem to the Muslims came as a great shock to the Christian world, and the new Pope called for a time of penitence, fasting, and a new Crusade while the Crusaders already in the Levant struggled to regain the Holy City.[31] The largest Crusader army so far began to make its way to the Levant, but the Byzantine Emperor fought against them in accordance with a treaty he had signed with Saladin.[32] Catholics further west managed to bring England and France into the fray, including the now-legendary Richard the Lionheart![]() . With Richard joining the Crusaders, they were able to retake several fortresses in the Jerusalem area and defeat Saladin's armies in a battle.[31] Richard took many prisoners during this campaign, and Saladin agreed to ransom them in exchange for money and Crusader-held prisoners. However, he wasn't able to cough up the dough fast enough, so Richard had the roughly 2,700 prisoners beheaded in full view of Saladin's distant army.[33] Saladin retaliated by killing his Christian prisoners. Despite this unpleasantness, Saladin still regarded Ricky Rick as the most honorable Christian lord, which says a lot about the others.[26]

. With Richard joining the Crusaders, they were able to retake several fortresses in the Jerusalem area and defeat Saladin's armies in a battle.[31] Richard took many prisoners during this campaign, and Saladin agreed to ransom them in exchange for money and Crusader-held prisoners. However, he wasn't able to cough up the dough fast enough, so Richard had the roughly 2,700 prisoners beheaded in full view of Saladin's distant army.[33] Saladin retaliated by killing his Christian prisoners. Despite this unpleasantness, Saladin still regarded Ricky Rick as the most honorable Christian lord, which says a lot about the others.[26]

After the French bailed out of the Crusade early, Richard struggled to keep going against the unstoppable forces of attrition and desertion, but he was finally forced to make peace with Saladin three years later.[34] Although the Third Crusade failed to retake Jerusalem, it did weaken the Muslims, and it did preserve the remaining Crusader states.

The Fourth Crusade (1202-1204)[edit]

Also known as the "Stupid Crusade," the Fourth Crusade was prompted by the stinging failure to retake Jerusalem the last time around. The Crusaders, this time mostly French, assembled a new army and made a contract with the Venetians to provide ships for transportation.[35] Around this time, a coup took place in the Byzantine Empire, deposing the emperor and exiling his young son.[36] Meanwhile, the Crusading army was a lot smaller and poorer than the French had hoped for, which was a problem because they could no longer afford to pay for the ships Venice had already built for them.[35]

In exchange for suspending the debt, the Venetians asked the Crusaders to very kindly attack the rebellious Croatian city of Zara. Yes, the Christian holy warriors were about to attack a Christian city. Despite the pope forbidding the campaign and threatening to excommunicate everyone involved, the Crusaders attacked Zara and retook it on behalf of the Venetians.[37] Money matters more than God.

Continuing towards Constantinople, the Crusaders received an offer from the deposed prince Alexius: if they helped him defeat the usurper who took his father's throne, Byzantium would pay the Crusaders' debts and join their campaign.[38] Unfortunately for poor Alexius, the city of Constantinople wasn't as loyal to his dynasty as he'd hoped. The Crusaders were forced to take the city by force, and upon regaining his throne, Alexius discovered that the imperial treasury had a lot less in it than he'd believed.[38] The Crusaders, who already didn't like the Byzantines, stuck around and effectively besieged the city before finally smashing in and brutally sacking it.[38] The Crusaders established a new Crusader state, the Latin Empire, in place of the fallen Byzantines, but it didn't last. With all the death and plundering, Constantinople never regained its glory, and the much later restored Byzantium was a shadow of what had come before.[6] The unstable Latin Empire, while it existed, siphoned Crusader resources and weakened their campaigns in the Levant.[35][note 1] The Pope was pissed.

The Fifth Crusade (1217-1221) and the Sixth Crusade (1228-1229)[edit]

After seeing the Byzantine Empire get wiped out by the most epic case of friendly fire in history, Pope Innocent III decided to refocus on Jerusalem and ensure that the Fifth Crusade would be under his control alone. He called for a new Crusade, but repeated failures had sapped Europe's enthusiasm for Muslim-killing.[40]

Eventually, the Crusaders built another army. However, they couldn't attack Jerusalem while an increasingly powerful Muslim Egypt was at their backs, so they decided to turn south instead. They successfully invaded Egypt, but on the road to Cairo, they were caught up in the flooding of the Nile and got wrecked by the Egyptians.[40] With no other real choice, they made peace with the Egyptians and went home. The end.

After failing to aid the Fifth Crusade, the Holy Roman Emperor at the time, Frederick II, decided to launch the Sixth Crusade by himself. However, after sailing into the Holy Land, Ol' Freddy figured out that his army was actually significantly weaker than the one which had participated in the Fifth Crusade.[41] Knowing that fighting the powerful Egyptians would be a stupid mistake, Frederick met with their Sultan and bluffed about the size of his army. Preoccupied with a rebellion in Syria, the Sultan agreed to hand over Jerusalem in exchange for a decade-long truce.[41] Boy, that was boring.

Seven, Eight, and Nine (1248-1254, 1270, 1272)[edit]

After the Albigensian Crusade, France emerged as a European superpower. Jerusalem, meanwhile, had been conquered yet again by the Muslims. To gain prestige for himself, the French king Louis IX decided to launch his own Crusade. The king decided it would not be possible to take Jerusalem while Egypt still stood, so he invaded, got caught up in the flooding of the Nile, got captured, and had to pay a hefty ransom to get himself out of prison.[42] Meanwhile, most of the other remaining Crusader territories were destroyed. Same old story.

The Eighth Crusade was again launched by Louis IX, and he decided to land in Tunis this time to attack Egypt from the west. However, the horrible conditions during the siege of Tunis resulted in the king's death.[43] His son, who wasn't quite as enthusiastic about the whole Middle Eastern adventurism thing, peaced out with the Tunisians in exchange for a free trade agreement.[43]

After France's failures, England decided to get in on the action for the Ninth Crusade. Despite some military victories, the English had problems to deal with at home, so they retreated again after losing the last Crusader castle in the entire region.[44] At this point, enthusiasm among Europe's rulers for Crusading was pretty much dead (although there were some grassroots unauthorized attempts to revive the crusading spirit later). That was the last real crusade for the Holy Land, an ignominious failure.

Other Crusades[edit]

Northern Crusades (1195-1290)[edit]

The Northern Crusades were initially a series of military campaigns against tribal pagans in the Baltic region (today Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia) largely undertaken by Christian monastic orders.[5] These wars date to 1195, when Pope Celestine III called for holy wars against the dirty barbarians of the north.[5] He did so on the encouragement of various nobles in the Holy Roman Empire, who wanted the spiritual benefit of the Crusades but also wanted to do their fighting closer to home.[45]

The Teutonic Order![]() , established in Jerusalem after the First Crusade, formed much of the backbone of the Crusader effort, invading the Prussian region on behalf of the Poles.[46] Other armies had largely failed to make significant inroads into the Baltic due to the rough terrain and the dogged guerrilla-style resistance of the natives.[45] The Teutons were professional and highly trained, however, so they had the best time making progress. As lands in Prussia were conquered by the Teutonic Knights, German settlers moved in to build towns and churches. After the pagans started accepting Christianity, though, the Teutonic Knights then proved themselves to be more interested in land and loot than religion, and they frequently burned Christian churches and slaughtered Christian converts.[45]

, established in Jerusalem after the First Crusade, formed much of the backbone of the Crusader effort, invading the Prussian region on behalf of the Poles.[46] Other armies had largely failed to make significant inroads into the Baltic due to the rough terrain and the dogged guerrilla-style resistance of the natives.[45] The Teutons were professional and highly trained, however, so they had the best time making progress. As lands in Prussia were conquered by the Teutonic Knights, German settlers moved in to build towns and churches. After the pagans started accepting Christianity, though, the Teutonic Knights then proved themselves to be more interested in land and loot than religion, and they frequently burned Christian churches and slaughtered Christian converts.[45]

To this day, most of the Baltic pagan religions are unknown, as they were completely annihilated so long ago. However, communities still exist that attempt to revive them.[47]

In keeping with the old tradition of fucking over other Christians, the Teutonic Order then decided to move against the Russian rump states left over after the Mongol invasions. The Russians were Eastern Orthodox Christians, but that didn't stop the Teutonic Order from invading in 1240 and sacking the city of Pskov.[48] The Teutons were overconfident, expecting that the Russians would be weakened by the recent savagery of the Mongols. Instead, the Russians (of course) fought a brilliant defensive campaign utilizing their home environment to weaken the invaders.[48] The final battle came at Lake Peipus in 1242, and the Crusaders suffered a catastrophic defeat.[49] The Russian victory halted eastward expansion for the Catholic Crusaders and saved Russia from further predation.[50] The Russian leader of the campaign, Alexander Nevsky, has been a Russian national hero ever since.[51]

Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229)[edit]

The Albigensian Crusade was called by Pope Innocent III against the Cathar heresy which had sprung up in southern France. What is known about Catharism was that it was Christian heresy that rejected the highly corrupt and totalitarian Catholic Church in favor of personal spiritualism and a rejection of the material.[52] Catharism may have a survival of or influenced by Gnostic sects,[53] and its practitioners were known to practice gender egalitarianism and vegetarianism.[54] Heresy was at that point in time treated just a seriously as treason. However, the Cathars drew their strength from lower nobility as well as the poor peasantry who were disillusioned with the wealth and splendor of the Catholic Church.[52]

This crusade was popular in northern France due to the opportunity for Frenchmen to win Crusader indulgences from the Church without having to travel all the way to Jerusalem.[55] A papal legate allegedly responded to the Crusaders' questions about conduct with the top page quote: "Kill them all. God will know his own."[55] And that's pretty much what the Crusaders did. Although the Crusade failed to completely remove the Cathar heresy, it did establish a number of more secular lords in the region who were more willing to work with the later-created Inquisition, which did succeed in destroying the heresy.[55]

The Albigensian Crusade likely had the highest number of deaths during any of the Crusades. The minimum death estimates are 200,000 over 20 years of warfare.[56] The violence was so pervasive that Raphael Lemkin, the Polish lawyer who coined the term “genocide” called it “ one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history".[57]

The Children's Crusade (1212)[edit]

The Children's Crusade was a religious movement[note 2] that swept through Europe during the year 1212, in which thousands of children took unsanctioned Crusader vows and tried to march out to reclaim Jerusalem.[58] The Crusade failed when the army of kiddos made it to the Mediterranean coast only to be stumped when the sea didn't part before them like they had expected. No, really.[59] At this point, the Pope figured out what was going on and told the kids to be good and go home to their parents. Allegedly, some of the children were tricked into slavery, and many probably died.

Bosnian Crusade (1235-1241)[edit]

Over the decades, the Bosnian Catholic Church had grown more and more independent from the Catholic Church, to the point where there were rumors about a Cathar antipope taking refuge in Bosnia.[60] These rumors have never been verified, but the Hungarians, who had long wanted an excuse to conquer the region, convinced the pope to call for a Crusade against the "Bosnian heretics".[61] Luckily for the Bosnians, the Mongols picked that exact moment to attack, destroying most of Hungary's armies and ending the Crusade.[62] The whole thing was pretty much a Hungarian conquest war thinly disguised as a divinely-sanctioned Crusade. Who woulda thought something like that could happen?

Crusade of the Poor (1309)[edit]

One of the popular grassroots "crusades", this incident is notable for targeting the Holy Land long after the last Crusader castle there had fallen.[63] Although Europe's rulers had lost interest in crusading by this point, many of the people and many local church officials were still determined to take back Jerusalem. Y'know, uh, somehow.

The church succeeded in whipping up popular support for a new crusade, but the effort found itself without any major backing from Europe's nobility. As a result, the ten thousand or so people from places like England, Picardy, Flanders, Brabant, and Germany sort of milled aimlessly around southern France hoping to seek an audience with the pope at Avignon.[63] True to the name, most of the would-be crusaders were from the bottom rungs of society, usually desperate peasants hoping to find glory and riches in the Holy Land.

When it became clear that nobody was going to help them reach the Holy Land, the "crusade" turned into a mob that ransacked southern France for provisions. Predictably, their worst violence was directed towards the Jews, and they massacred Jews all over France.[63] After this hideous bloodbath, the peasants sort of gave up and went home.[64]

Shepherds' Crusade (1320)[edit]

Religious fervor in France stirred up what was probably the most violent of the "popular" crusades in 1320. The Shepherd's Crusade was the result of local church officials whipping up religious fervor, and Pope John XXII in Avignon was terrified of the movement and tried to order them to disperse before they reached his papal palace.[65] When the movement reached Paris, they were infuriated when Philip V refused to lead them to the Holy Land.[66] At that point, the movement turned into a peasant rampage across France as they swept the countryside to attack royal castles and officials and uncooperative priests. They also massacred Jews across France (of course) and then moved south to Spain to kill even more Jews.[67] The lucky Jews received the offer of baptism or death, most of them were just robbed and murdered.

Ultimately, this crusade ended thanks to the efforts of Philip V and his armies, as the king viewed the "crusade" as nothing more than a disloyal revolt. Royal armies defeated the wannabe crusaders in several battles, and most of the crusaders were then hanged as traitors by the authority of the French Crown.[65]

The Crusade of Varna (1443-1444)[edit]

The Crusade of Varna is the name given to an unsuccessful military campaign by multiple European monarchs (Poland, Hungary, Bohemia, Croatia, Wallachia, Lithuania, Serbia, Moldova) to check the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. After the old sultan abdicated in favor of his more inexperienced son, the Eastern Europeans believed they saw an opportunity to assault the Ottomans and push them out of the Balkans.

Tactical problems forced the Crusaders to bypass multiple fortresses, and the Ottomans defeated them at the devastating Battle of Varna.[68] This battle crushed most of the armies of Eastern Europe, weakening them immensely to the point where they were not able to come to the rescue of the Byzantine Empire when the Ottomans finally came for them in 1453.[69] Constantinople fell, and the Ottomans expanded into Europe for the next handful of centuries.

The Last Crusade (1938)[edit]

Indiana Jones and his father, James Bond, fought Nazis and found the Holy Grail. Mr. Bond used it to become immortal.[70]

Consequences of the Crusades[edit]

The importance of the Crusades (at least the first four) in European history cannot be overstated. The Crusades helped to re-link Western Europe to the Silk and Spice roads. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire that part of the world remained largely isolated from eastern trade routes due to instability and a general lack of interest.[71][72] Crusaders returning home often brought with them "exotic" eastern goods and Western Europeans were willing to trade for them; this desire for silks and spices encouraged the Western Europeans to try and find ways to cut out the middlemen and trade directly with China and India, encouraging countries to begin exploring the world.[73] Along with the flow of goods came a flow of ideas.

Rather than a bunch of stupid barbarians who destroyed everything they found, the Muslim conquerors of antiquity were scholars who embraced the cultures they found and preserved for study many ancient Greek and Latin texts that had been forgotten about in the West.[74][note 3] During the Crusades, Christians translated these texts, as well as further developments by Muslim scientists, and shipped them home through Medieval Europe's trading hubs — most significantly the Italian city-states.[74] The rediscovery of these texts in the West, as well as a renewed appreciation for the ancient heritage, helped to spark the Italian Renaissance, and are the reason for Arabic al- prefixes on many words related to the sciences (al-chemy, al-gebra, al-gorithm, etc).[75] Due to this, many later European thinkers came to regard the Crusaders as barbarians (not helped by reports of them doing everything up to and including cannibalism) and Saladin in particular became such a respected figure as a learned and chivalrous opponent that Dante Alighieri placed him among the "virtuous pagans" who did not have to go to Hell.[76]

Conversely the Crusades helped cement a form of radical Islam that would continue centuries later, not helped by Muslims in the East encountering the Mongol army in the same period. Many of the interpretations of scripture popular with modern jihadis were written in this period, particularly the interpretation of Quran 9:5 as the "sword verse."[77] Unfortunately the new trade routes brought back more than just silks, spices, and books; rats carrying infected fleas hitched rides on ships to Western Europe, bringing about the Black Death and resulting in the death of roughly one third of its population. That really sucks.

In modern usage, a "crusade" is any mission or movement based on strong moral or ideological backing, such as Campus Crusade for Christ. Often, it denotes a foolish endeavor, such as, again, Campus Crusade for Christ.

Crusade vs Jihad[edit]

Muslim demagogues often compare American servicemen to European crusaders in propaganda.[78] You can thank George W. Bush (and Wahhabism) for that one. Well, that and U. S. Military arms inscribed with passages from the New Testament. And the US military operating an aircraft called the "Crusader", in addition to almost fielding another aircraft and a self-propelled gun with the same name.[79]

While Jihad has a few more meanings than merely 'killing infidels', "Jihad of the Sword" means "waging war against the enemies of Allah", and "Jihad of the Tongue" means spreading Islam. In these senses, "Jihad" and "Crusade" are more or less mirror images of each other. The people performing Jihad, called "Mujahideen", are effectively Crusaders of a different religion. In more modern terms, the "Offensive-Jihad" of Sayyid Qutb that most non-Muslims think of when they hear the term 'Jihad', can be more or less summed up with the page quote. The irony should not be lost on anyone.

Pseudohistory[edit]

If someone ever tries to tell you that the Catholic church and the Jews of Europe were on the same side during the Crusades, it's up to you to determine whether that's an example of fractal wrongness or not even wrong. Not only were much of Europe's Jews marginalized, ghettoized, and pogromed, before, during, and after the period,[80][81][82] no Jews had any reason to participate in the 'reclamation' of Jerusalem for global Christianity. Instead, Jews were the subject of much Crusader violence on account of their not being Christians.[83][84]

Modern times[edit]

The rise of the alt-right has brought with it calls for a renewed Crusade against DAESH specifically, but more "based" people would like to purge the entire Middle East. Of course, the people shouting "Deus Vult!" on /pol/ aren't actually going to pick up a rifle and risk their own skins. They're...uh...busy. They have a perfectly logical response to this though: Calling you a cuck. Over, and over, and over again.

See also[edit]

- Jerusalem

- Inquisition

- Thirty Years War

- Taiping Rebellion

- Lord's Resistance Army

- Massacres in the name of a peaceful faith

External links[edit]

- The Crusades - Pilgrimage or Holy War?

- A virtual college course on the crusades

- Europe : The First Crusade Extra History

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Ironically, since the Byzantine Empire was for very long a “shield” for Western Europe, the Fourth Crusade ended up making the Christendom more vulnerable than ever, and indeed, only a few centuries after its fall, the Ottoman Empire managed to besiege Vienna.[39]

- ↑ Possibly fictitious.

- ↑ Just don't tell that to the Islamophobes.

References[edit]

- ↑ The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade by M. D. Costen (1997) Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719043328.

- ↑ The History of England

- ↑ Cathar Wars or "Albigensian Crusade" Cathar Info

- ↑ Christiansen, Erik (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books. p. 287. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 What Were The Northern Crusades? World Atlas

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Sack of Constantinople Britannica

- ↑ The First Crusade And The Establishment Of The Latin States Britannica

- ↑ The Popes and the Crusades Munroe, Dana C. "American Philosophical Society". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Vol. 55, No. 5 (1916), pp. 348-356.

- ↑ The Crusades, PBS

- ↑ William of Tyre, “The Capture of Jerusalem”

- ↑ Turks, Conquests and the Crusades Macrohistory

- ↑ Byzantine-Seljuk Wars and the Battle of Manzikert Hickman, Kennedy. ThoughtCo. 09.26.17

- ↑ A Timeline of the First Crusade, 1095 - 1100 Cline, Austin. ThoughtCo. 05.30.18

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 The Crusades (1095–1291) Metropolitan Museum of Art]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 First Crusade Ancient History Encylopedia

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 The People's Crusade Snell, Melissa. ThoughtCo. 07.18.18

- ↑ The Pursuit of the Millennium, Norman Cohn, Pimlico 2004 (1957), p.68.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Tafurs.

- ↑ The Pursuit of the Millennium, Norman Cohn, Pimlico 2004 (1957), pp.65-67.

- ↑ The Crusader states Britannica

- ↑ Siege of Edessa Britannica

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Second Crusade Ancient History Encylopedia

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Holy smoke Castor, Helen. The Guardian. 02.01.08

- ↑ Nicolle, David (2009). The Second Crusade 1148: Disaster outside Damascus. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-354-4.

- ↑ Battle of Hattin, 4 July 1187 History of War

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Saladin Biography Biography Online

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim (1992). The Medieval Siege (New ed.). Woodbridge: The Boydell. p. 296. ISBN 0851153577.

- ↑ Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2012). Jerusalem : the Biography (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. p. 222. ISBN 0307280500.

- ↑ First Crusade: Siege of Jerusalem Hull, Michael D. (June 1999). Military History.

- ↑ This Day in Jewish History / Saladin Captures Jerusalem From the Crusaders Green, David B. Haaretz. Oct 02, 2012

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 The Third Crusade Britannica

- ↑ Brand, Charles M. (1962). "The Byzantines and Saladin, 1185-1192: Opponents of the Third Crusade". Speculum. 37 (2): 167–181. doi:10.2307/2849946. JSTOR 2849946.

- ↑ Richard The Lionheart Massacres The Saracens, 1191 Eyewitness to History

- ↑ The Third Crusade History Learning.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Fourth Crusade Britannica.

- ↑ Nicolle, David (2011). The Fourth Crusade 1202-04 - the Betrayal of Byzantium. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd. p. 65. ISBN 978 1 84908 319 5.

- ↑ Siege of Zara Britannica

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Fourth Crusade HistoryNet

- ↑ Roberts, J. M. (1986). The Triumph of the West. BBC. p. 132. ISBN 0563200707.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 The Fifth Crusade History Learning.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 The Sixth Crusade History Learning

- ↑ The Seventh Crusade History Learning

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 The Eighth Crusade

- ↑ "Edward I", Michael Prestwich, University of California Press, 1988

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Northern Crusades. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Van Duren, Peter (1995). Orders of Knighthood and of Merit. C. Smythe. p. 212. ISBN 0-86140-371-1.

- ↑ Romuva (Neo-Paganism) in Lithuania True Lithuania

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Lake Peipus: Battle on the Ice. Warfare History Network.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle on the Ice.

- ↑ Riley-Smith Jonathan Simon Christopher. The Crusades: a History, USA, 1987,ISBN 0-300-10128-7, p.198.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Order of Alexander Nevsky.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 The Cathar HeresyDr. Stephen Haliczer. Northern Illinois University

- ↑ Cathars & Albigenses: What Was Catharism? Learn Religions.

- ↑ A Five-Minute Guide to the Cathars. Medievalists.net

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Albigensian Crusade Britannica

- ↑ Colin Tatz, Winston Higgins, The Magnitude of Genocide 2016

- ↑ Lemkin, Rafael ‘’Lemkin on Genocide’’ 2012

- ↑ Children's Crusade Britannica

- ↑ Bridge, Antony. The Crusades. London: Granada Publishing, 1980. ISBN 0-531-09872-9

- ↑ Van Antwerp Fine, John (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, pp. 143–146, 277, ISBN 0472082604

- ↑ Van Antwerp Fine, John (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, pp. 143–146, 277, ISBN 0472082604

- ↑ Hamilton, Janet; Hamilton, Bernard; Stoyanov, Yuri (1998). Christian Dualist Heresies in the Byzantine World, C. 650-c. 1450: Selected Sources. Manchester University Press. p. 265. ISBN 071904765X.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Crusade of 1309. Erenow.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Crusade of the Poor.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Shepherds' Crusade, Second (1320). Erenow.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Shepherds' Crusade (1320).

- ↑ Shepherds Crusade 1320. Medieval Crusades. Blogspot.

- ↑ The Crusade of Varna War History Online Jul 11, 2016. Yulia Dzhak

- ↑ Madden, Thomas F. (2006). "9". The New Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-7425-3823-8.

- ↑ "You have chosen... wisely."

- ↑ Silk Road Ancient History Encyclopedia

- ↑ Silk Road Britannica

- ↑ The Silk Road: Connecting People and Cultures Kurin, Richard. Smithonian 2002

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 The Real Significance of the Crusades Byrne, David. Crisis Magazine. 07.03.13

- ↑ Bridges: Documents of the Christian-Jewish Dialogue ed. Franklin Sherman. Bulding a New Relationship (1986-2013) Vol 2.

- ↑ Saladin (c. 1138-1193) David Van Biema. TIME. 12.26.99

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/asma-afsaruddin/islam-not-monolithic_b_8955168.html

- ↑ World Islamic Front Statement, courtesy of the Federation of American Scientists

- ↑ http://www.army-technology.com/projects/crusader/

- ↑ The Pogroms of 1189 and 1190 Eislund, Seth. Historic UK.

- ↑ Anti-Semitism In Medieval Europe Britannica

- ↑ Pogroms Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ This Day in Jewish History / Crusaders Massacre the Jews of Mainz Green, David B. Haaretz 05.27.14

- ↑ https://www.jewishhistory.org/the-first-crusade/ The First Crusade] Jewish History