Völkisch movement

| Suppress the dissenters Fascism |

| Bundle of rods |

| Fascists |

| Groups |

“”[Germany] contained not only the largest workers movement in Europe at that time, but also one staunchly opposed to racism and antisemitism. Nevertheless, the völkisch movement with its antisemitism had its roots in the German past; like worms destroying a cheese völkisch prophets and movements started at the periphery of politics, eating their way to the center wherever the political organism was weakest and started to rot — in this case during the Weimar Republic.

|

| —George L. Mosse |

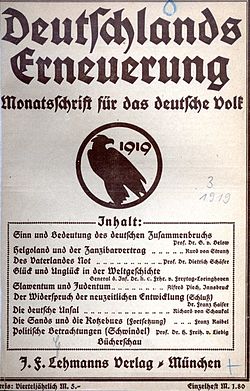

The völkisch movement (German: Völkische Bewegung), also known as folkist movement was a German ethnocratic communitarian movement that had great presence in the Germany and Austria from the late 19th century to the end of World War II.[2]:10[3]:123[4]:48 It included political parties such as the Nazi Party and the German National People's Party![]() , as well as Freikorps

, as well as Freikorps![]() militia associations and terrorist organizations such as the Organisation Consul,

militia associations and terrorist organizations such as the Organisation Consul,![]() clubs, loose groups and individuals and produced a large number of publications.[2]:60, 171[5][6][7]:21, 53

clubs, loose groups and individuals and produced a large number of publications.[2]:60, 171[5][6][7]:21, 53

Their beliefs were built around the slogan of blood and soil;![]() the blood ties of the German people and the land on which the German people live, and sees Germany itself as a living body (Volkskörper).[8][9] The movement entered mainstream popularity in the 1870s Germany, with its ideology being racist and anti-Semitic. Their vilification of Jews began in the early 20th century, and the völkists saw Jews as foreigners and considered them to be "neither a Nordic race nor an Aryan race."[10][11]

the blood ties of the German people and the land on which the German people live, and sees Germany itself as a living body (Volkskörper).[8][9] The movement entered mainstream popularity in the 1870s Germany, with its ideology being racist and anti-Semitic. Their vilification of Jews began in the early 20th century, and the völkists saw Jews as foreigners and considered them to be "neither a Nordic race nor an Aryan race."[10][11]

The Völkists thrived thanks to agrarianism![]() and populism, partly due to its opposition to the growing modernism of 20th-century society.[3]:123 The Völkisch movement also believed in a national revival and that this revival would only occur through the Germanization of Christianity (see Positive Christianity) or by outright rejection of it.[12]

and populism, partly due to its opposition to the growing modernism of 20th-century society.[3]:123 The Völkisch movement also believed in a national revival and that this revival would only occur through the Germanization of Christianity (see Positive Christianity) or by outright rejection of it.[12]

Nazi Germany essentially served as the culmination of the movement, and died along with it.[13][14][15] However, its principles have experienced a revival in various German neo-pagan and neo-Nazi groups, as well as the far-right movements that emerged alongside Trumpism.[16][17][18]

Definition and goals[edit]

The movement itself had no unified belief system per se, with the collective goal of the sub-movements being "reviving the traditions of the historical Germanic peoples".[19][20] Although the Völkisch movement significantly predates the Weimar Republic-era conservative revolution![]() , the Völkisch movement was considered one of the three major parts of the said revolution.[3]:123[21]

, the Völkisch movement was considered one of the three major parts of the said revolution.[3]:123[21]

The movement postulated that all other peoples in the world were "people who grew up within a certain area of land, who were forcibly united into one country by artificial means, and eventually became a nation", and only the Germanic people belonging to the Germany were "the only successful example of a people who have survived strongly in the great outdoors without any artificial interference". However, while primitive Germanic people had their strengths, due the people themselves receiving too little positive interference, they unknowingly fell behind these "artificial" peoples in some fields and rapidly weakened throughout history. Supposedly, the primitive Germanic people had the power to "easily destroy even the Roman Empire, which had conquered all of Europe", but the German people of the 19th century no longer had such power. Austria and Prussia, which were supposed to be German nations, were defeated by Britain and the United States in military and economy terms, and were oppressed by France and Russia in terms of army and patriotism. Thus, they believed that "reviving the good old Germanic traditions" was considered to be the most important thing for keeping their country alive.[20][22][23]

To do so, a major priority was to "eliminate the influence that Christianity and (especially) the Jews" in order to restore "the German people to their original form". Christianity, which was very important to most Europeans, was not important from the perspective of the movement, and Christianity to have its non-Germanic elements removed, or to be abandoned altogether.[24][25]

The supporters of the Völkisch movement wanted to return to the Germanic/German people as they were before the influence of other peoples, so they sought to revive the primitive Germanic faith before Christianity and to "restore the pure Germanic nation". All "Jews" who invented the existence of Jesus Christ and tried to break the German/European warrior culture through religious doctrines that promoted weakness, were to be expelled from Germany.[11][26][27]

According to the Völkisch movement's theory, the true Germanic people had white skin, blue eyes, blonde hair, little body odor, are muscular, tall, and prefer cold climates. The movement believed that they themselves were the descendants or survivors of the ancient Germanic people. It was believed that for Germans to fully regain their "Germanic purity," they would need to spend decades intermarrying with Nordic peoples who had the superior genetics of the ancient Germanic peoples and increasing their offspring one after another.[28][29]

During the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party took all these principles to even more extreme levels, targeting non-Jews, such as Catholics, Jehovah's Witnesses, Socialists, Communists, and homosexuals, to be purged and killed, with the goal of allowing mainstream Germans to quickly replace "undesirables".[30][20]

History[edit]

Early days[edit]

The völkisch movement began to emerge in the second half of the 19th century, primarily inspired by nostalgia towards "harmonic" Holy Roman Empire (aka the First Reich), being influenced by German romanticism.[8] As such, Völkisch movement carries connotations of counter-enlightenment.[31][32] Additionally, in the aftermath of the German revolutions of 1848–1849![]() , antisemitic sentiment started to permeate in Germany.[33] At the time, many Germans believed in a hierarchical class order (estates of the realm

, antisemitic sentiment started to permeate in Germany.[33] At the time, many Germans believed in a hierarchical class order (estates of the realm![]() ), but became skeptical of the new class system (i.e. social class and/or Marxian class theory

), but became skeptical of the new class system (i.e. social class and/or Marxian class theory![]() ) that emerged after the Industrial Revolution. In particular, the common people in German-speaking countries did not feel close to the German Empire, which was unified in 1871, and were very dissatisfied with the delay in German unification led by Prussia. These conditions led to the Völkisch movement to begin infesting.[28][34]

) that emerged after the Industrial Revolution. In particular, the common people in German-speaking countries did not feel close to the German Empire, which was unified in 1871, and were very dissatisfied with the delay in German unification led by Prussia. These conditions led to the Völkisch movement to begin infesting.[28][34]

People involved in the Völkisch movement rejected the Lumières![]() of the Prussian monarchy and the militarism of the Junkers

of the Prussian monarchy and the militarism of the Junkers![]() , and tended to prefer a proverbial "cult of eugenics" among the "race" and the promotion of "individualistic military action" in the struggle for hegemony with foreign nations led by the "state."[35]

, and tended to prefer a proverbial "cult of eugenics" among the "race" and the promotion of "individualistic military action" in the struggle for hegemony with foreign nations led by the "state."[35]

The word "Völkisch" initially meant the "lower class" where commoners and the masses were located, but the popular movement gave it a "noble nuance" and transformed it into a word that suggests the "superiority of the German people over other peoples".[20] Many thinkers of Völkisch movement, such as Arthur de Gobineau, Georges Vacher de Lapouge![]() , Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Ludwig Woltmann

, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Ludwig Woltmann![]() , and Alexis Carrel

, and Alexis Carrel![]() strongly criticized the Christian faith believed by the upper-class nobility and supported Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which advocated equality for all (i.e. the abolition of classism.) Their reading of Darwin's "The Theory of Evolution" led them to advocate the ideal of "racial struggle" and a "hygienist" vision of the world.[8][36][37][4]:24, 44, 62 However, there were also Völkists ideologues who were vehemently opposed to Darwnism, such as General Erich Ludendorff

strongly criticized the Christian faith believed by the upper-class nobility and supported Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which advocated equality for all (i.e. the abolition of classism.) Their reading of Darwin's "The Theory of Evolution" led them to advocate the ideal of "racial struggle" and a "hygienist" vision of the world.[8][36][37][4]:24, 44, 62 However, there were also Völkists ideologues who were vehemently opposed to Darwnism, such as General Erich Ludendorff![]() , Mathilde Ludendorff

, Mathilde Ludendorff![]() (the "Völkist feminist icon") and Julius Langbehn

(the "Völkist feminist icon") and Julius Langbehn![]() .[38]

.[38]

The supporters of the Völkisch movement believed that the world's ethnic groups should be classified and hierarchically categorized based on "racialism." They argued that the Aryan race, which belonged to Germans and Scandinavian peoples, should be at the top of the white race, with white people still being the pinnacle of all races. Based on this core theory, Völkisch thinkers believed that the German people should restore their "primordial purity", both biologically and mystically.[39][40][41]

They also considered the presence of the Jews to be a threat to the purity of the German race. According to the Völkisch movement's theory, Christian-based religions invented by the Jews had "contaminated" the European continent by artificially interfering with the evolutionary process of humankind and brainwashing people into the idea of inequality and chosenness. It was deemed that such religions had to be eliminated to insure German prosperity.[8]

Early 20th century[edit]

The term "Völkisch" was forming a new nationalism that transcended national boundaries in German-speaking countries, while the German socialist parties deliberately treated "proletariat" as a synonym for "Völkisch," significantly shifting political thought in the German region to the left. The leftists believed that the "anti-privileged" and "anti-Christian" elements present in the popular movement could also be widely applied to the middle class, and that they would eventually be able to embrace the ideals of socialism.[42]

The main activities of the popular movement were centered around Germanic mystical societies, which attempted in various ways to revive the indigenous German and pagan traditions. They often used quasi-theosophical and esoteric methods that were not based on scientific criteria.[43]

Due to a strong desire to restore blood purity, a "secret society" called the "Germanenorden" (Germanic Knights) was established in Berlin in 1912, with all of its members made to wear medieval clothing. To join the group, members had to prove that they didn't have "the blood of an non-Aryan" and swear that their spouses would also be of pure Aryan blood. Local branches of the sect regularly held pagan altars and midsummer carnivals, during which participants read the works of German mystics together.[4]:42[44][45] Another society of note was the Thule Society![]() , where Hitler and handful of other Nazi big-wigs would enter into politics.[note 1][46][47] This so-called "playful experimentation" with German romanticism and folklore spread not only throughout the German Empire, but also in Austria, Czechia, and Luxembourg.[48]

, where Hitler and handful of other Nazi big-wigs would enter into politics.[note 1][46][47] This so-called "playful experimentation" with German romanticism and folklore spread not only throughout the German Empire, but also in Austria, Czechia, and Luxembourg.[48]

On the other hand, there were also groups that brought them together. For example, the community of "Monte Verita" (Mountain of Truth) was founded in Ascona, Switzerland in 1900 by Swiss art critic Harald Szeemann (not be confused with that Harald Szeemann![]() ), and aimed to make money by meticulously studying beautiful landscapes, architecture, and tourist attractions in German-speaking countries and introducing them to foreign travel agencies. "Monte Verita" described itself as "the southernmost of a people's movement, following a simple and primitive lifestyle like the Nordic peoples."[49]

), and aimed to make money by meticulously studying beautiful landscapes, architecture, and tourist attractions in German-speaking countries and introducing them to foreign travel agencies. "Monte Verita" described itself as "the southernmost of a people's movement, following a simple and primitive lifestyle like the Nordic peoples."[49]

The founding of umbrella organizations on the eve of the First World War did not change the fact that the Völkisch movement remained fragmented and had few members. However, its ideas had already had a significant social impact before 1914 through multipliers such as the German National Commercial Assistants' Association, student clubs and associations, and the youth movement, as well as through the widely circulated works of Paul de Lagarde![]() , Julius Langbehn

, Julius Langbehn![]() , and H.S. Chamberlain.[50]

, and H.S. Chamberlain.[50]

The beginning of the First World War led to a loss of importance of the Völkisch movement, since there was other kinds of nationalism in the air. Many Völkisch publications being subject to preventive censorship and were also repeatedly banned. Despite the war, their primary focus was on the internal enemy. With the war, foreign policy became the focus of attention in Germany, and the nationalists produced little of their own on this issue. To the extent that ideas were expressed about Germany's foreign policy orientation, they were contradictory and incapable of reaching a consensus. The nationalists therefore sought to join forces with the old nationalism in the First World War.[51]

From Weimar Republic to Nazi Germany[edit]

After World War I, the political turmoil and instability in Germany created an environment ripe for various popular and radicalist movements. Some participants in the popular movement believed that the cause of the failure of the German Empire was that the old imperial system was too attached to Christian traditions. During the Weimar Republic, there were many popular movement groups, but the total number of adherents was not very large.[52]

As of consequence, some Völkisch thinkers began attempts to create a "true German faith" (Deutschglaube) by "reviving the faith in the ancient Germanic gods" and to counter the Catholic and Protestant churches that continued to wield influence, even after the war.[53][54]

The proponents of the occult, such as Ariosophy, were associated with the theory of the Völkisch movement in the 1920s, and artists such as Ludwig Fahrenkrok![]() and Fidus

and Fidus![]() also influenced the Völkisch movement, creating many artworks depicting the primitive Germanic peoples.[52] In May 1924, Kaiser Wilhelm II of the former Empire praised the Völkisch movement as having the power to "transcend Christianity and unify the entire German people", and the Kaiser's praise helped the Volksmovement to spread politically to both the left and right in Germany. Thusly, the rhetoric of the Völkisch movement was seen as "heroic" in German politics, instead of being seen as creed of "calculating politicians".[55]

also influenced the Völkisch movement, creating many artworks depicting the primitive Germanic peoples.[52] In May 1924, Kaiser Wilhelm II of the former Empire praised the Völkisch movement as having the power to "transcend Christianity and unify the entire German people", and the Kaiser's praise helped the Volksmovement to spread politically to both the left and right in Germany. Thusly, the rhetoric of the Völkisch movement was seen as "heroic" in German politics, instead of being seen as creed of "calculating politicians".[55]

Meanwhile, the nationalists rejected everything that was praised as progress in the Weimar Republic. They rejected both the Marxism of the left-wing parties and democracy.[56] Although the nationalists officially condemned political violence, they maintained links with right-wing extremist militia and other cells, participating in the Kapp Putsch![]() and the Beer Hall Putsch. They were also involved in assassinations and murders of feminist activists. In addition to the change in the political system, the influx of demobilized soldiers into their organizations may have contributed to the radicalization of the nationalists.[57]

and the Beer Hall Putsch. They were also involved in assassinations and murders of feminist activists. In addition to the change in the political system, the influx of demobilized soldiers into their organizations may have contributed to the radicalization of the nationalists.[57]

After the number of ethno-nationalist organizations and supporters had initially increased significantly after 1918, with the Deutschvölkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund![]() (German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation) briefly forming an influential cartel of ethno-nationalist associations, and them entering state parliaments and the Reichstag. From c. 1924/1925, due to structural issues, the ethno-nationalist movement was gradually pushed into political marginalization by ideologically closer towards National Socialism, the new melting pot of the German radical right.[58][59]

(German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation) briefly forming an influential cartel of ethno-nationalist associations, and them entering state parliaments and the Reichstag. From c. 1924/1925, due to structural issues, the ethno-nationalist movement was gradually pushed into political marginalization by ideologically closer towards National Socialism, the new melting pot of the German radical right.[58][59]

During this period, especially after the re-foundation of the NSDAP, differences were emphasized by both sides. They often expressed themselves as a generational conflict between old nationalists and young National Socialists. Nevertheless, there were close similarities between the two movements - especially ideologically. The most obvious overlap in personnel between nationalists and National Socialists was in the settlement with the Artaman League![]() .[60]

.[60]

Although individual ethno-nationalist organizations and leaders joined National Socialism - to varying degrees - and the transfer of power to Hitler was welcomed by the majority of ethno-nationalist groups, the ethno-nationalist organizations (and their leadership) that continued to exist after 1933 quickly lost importance. Some were absorbed into the National Socialist organizational structure, the majority dissolved or eked out a shadowy existence that was tantamount to dissolution until; any that remained were detained or banned by the victorious Allied Powers![]() countries after the end of the war. By 1945, many supporters had joined the criminal blood-and-soil ideology of the Third Reich.[61][62][7]

countries after the end of the war. By 1945, many supporters had joined the criminal blood-and-soil ideology of the Third Reich.[61][62][7]

Following 1945[edit]

Völkisch movement had peaked with the Nazis, and after the latter got beaten shitless during World War II, the former also crashed with force. Isolated attempts at a new organizational beginnings after 1945 have been unsuccessful, with the exception to the Artgemeinschaft![]() (Artgemeinschaft Germanic Faith Community), which was founded by a former SS officer named Wilhelm Kusserow.[63][64][65] Additionally, Heathenry / Germanic Neopaganism

(Artgemeinschaft Germanic Faith Community), which was founded by a former SS officer named Wilhelm Kusserow.[63][64][65] Additionally, Heathenry / Germanic Neopaganism![]() has been scrutinized for its ancient Germanic traditionalism being ripe for racialism.[16][66][67]

has been scrutinized for its ancient Germanic traditionalism being ripe for racialism.[16][66][67]

Elements of German ethnic religion and worldviews can also be found beyond these German neo-Germanic pagan and folkist groups; they are part of the international neo-pagan movements, mixed with ideologies of other origins and in a frequently mediated form, and often no longer immediately recognizable as ethnic. These remnants of ethnic thinking are not limited to small subcultures, but find their way into wider social circles and widespread distribution through popular genres through their mediation, which goes hand in hand with their popularization. According to German literary scholar Stefanie von Schnurbein![]() , products of fantasy literature based on the model of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings

, products of fantasy literature based on the model of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings![]() can also be classified in this context. She also cites Stephan Grundy's

can also be classified in this context. She also cites Stephan Grundy's![]() best-selling novel "Rheingold" as another example.[68]

best-selling novel "Rheingold" as another example.[68]

Ideological elements of the movement can also be found in international right-wing extremism and in associations such as the Allgermanische Heidnische Front![]() (AHF),[69]:76-84 and partly in various alternative movements and subcultures. Several neo-pagan Asatru religious communities either reject or downplay relations with National Socialism and the neo-Nazi scene, which does not exclude the spread of elements of ethnic origin.[note 2][69]:276

(AHF),[69]:76-84 and partly in various alternative movements and subcultures. Several neo-pagan Asatru religious communities either reject or downplay relations with National Socialism and the neo-Nazi scene, which does not exclude the spread of elements of ethnic origin.[note 2][69]:276

The esoteric traditions of a nationalistic "right-wing esotericism" are currently being taken up by some right-wing extremist groups to legitimize their racism.[70] Völkisch-style ethno-nationalistic elements are also often used within the music genres of neofolk or pagan metal.[71][72]

In an interview with Welt am Sonntag in 2016, the then chairwoman of the AfD, Frauke Petry, advocated removing the term "völkisch" from its Nazi connections and giving it a positive connotation. [73][74]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ For further info, see Nazi occultism.

- ↑ For further info, see Asatru#Racist_interpretations.

References[edit]

- ↑ Mosse, G. L. (2021). The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. University of Wisconsin Press. Preface/Page ix. ISBN: 9780299332044

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Campbell, B. (2021). The SA Generals and the Rise of Nazism: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN: 9780813184326

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ferrera, M. (2024). Politics and Social Visions: Ideology, Conflict, and Solidarity in the EU. OUP Oxford.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Mees, B. (2008). The Science of the Swastika. Central European University Press. ISBN:9786155211577

- ↑ Politics in German Literature (1998) Camden House. Page 83. ISBN:9781571130822

- ↑ Mosse, G. L. (2021). The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. University of Wisconsin Press. Page 159. ISBN: 9780299332044

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Messman, C. A., Messman, C. (1977) Völkisch Paramilitarism in the Weimar Republic: A Case Study in Power Relationships (Part 1). University of Wisconsin--Madison.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Camus, Jean-Yves; Lebourg, Nicolas (2017). Far-Right Politics in Europe. Harvard University Press. Pages 16-18. ISBN 9780674971530.

- ↑ Victor, G. (1998). Hitler: The Pathology of Evil. Brassey's. Page 138. ISBN:9781574881325

- ↑ Joseph W. Bendersky (2000) A History of Nazi Germany: 1919–1945. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8304-1567-0.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Dunt, I., Lynskey, D. (2024) Fascism: The Story of an Idea (An Origin Story Book). Orion. ISBN: 9781399612937

- ↑ Heschel, S. (2008) The Aryan Jesus: Christian theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany. Princeton University Press. Page 44. ISBN:9780691125312

- ↑ Mosse, G. L. (2021). The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. University of Wisconsin Press. Page 248. ISBN: 9780299332044

- ↑ Stackelberg, R. (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany. Taylor & Francis. ISBN: 9781134393855

- ↑ Fischer, C. (2002). The rise of the Nazis. Manchester University Press. Page 44. ISBN: 9780719060670

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 White, Ethan Doyle (2017). "Northern Gods for Northern Folk: Racial Identity and Right-wing Ideology among Britain's Folkish Heathens". Journal of Religion in Europe. 10 (3): 259–261. doi:10.1163/18748929-01003001. ISSN 1874-8929.

- ↑ Gardell, Mattias (2003). Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Duke University Press. p. 17. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11vc85p. ISBN 978-0-8223-3059-2. JSTOR j.ctv11vc85p.

- ↑ Pleasure and Pain in US Public Culture. (2024). University of Alabama Press. Page 10. ISBN:9780817361709

- ↑ Hans Jürgen Lutzhöft (1971) Der Nordische Gedanke in Deutschland 1920–1940 (Stuttgart. Ernst Klett Verlag), p. 19. ISBN: 978-3129054703

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Dohe, Carrie B. (2016) Jung's Wandering Archetype: Race and religion in analytical psychology. Routledge. Page 36. ISBN 978-1-317-49807-0.

- ↑ Flipo, F. (2018). The Coming Authoritarian Ecology. Wiley. Page 235. ISBN: 9781786302427

- ↑ Mission und Gewalt: der Umgang christlicher Missionen mit Gewalt und die Ausbreitung des Christentums in Afrika und Asien in der Zeit von 1792 bis 1918/19. (2000). Steiner. Page 267.

- ↑ Cronenberg, A. T. (1970). The Volksbund Für Das Deutschtum Im Ausland: Völkisch Ideology and German Foreign Policy, 1881-1939. Stanford University. Page 54.

- ↑ Schmidt-Rohr, Georg (1932). Die sprache als bildnerin der völker: eine wessens- und lebenskunde der volkstümer [Language as the creator of peoples: a study of the essence and life of peoples] (in German). Ohio State University: E. Diederichs.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Ewald Banse. Landschaft und Seele. München 1928, p. 469. ISBN: 9783486758085 (In German)

- ↑ Mosse, G. L. (2024). Masses and Man: Nationalist and Fascist Perceptions of Reality. University of Wisconsin Press. Page 67. ISBN: 9780299347642

- ↑ Whitehead, G. D. (2024). The Performance of Viking Identity in Museums: Useful Heritage in the British Isles, Iceland, and Norway. Taylor & Francis. ISBN: 9781351036009

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas (1985). The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology (1992 ed.). New York University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8147-3060-7.

- ↑ Dupeux, Louis (1992) La Révolution conservatrice allemande sous la République de Weimar. Kimé. p. 115–125. ISBN 978-2908212181

- ↑ Birken, Lawrence (1994). Volkish Nationalism in Perspective. The History Teacher 27 (2): 133–143. doi:10.2307/494715. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 494715.

- ↑ Hatheway, J. G. (1992). The Ideological Origins of the Pursuit of Perfection Within the Nazi SS. (n.p.): University of Wisconsin--Madison. Page 87.

- ↑ Sternhell, Z. (2010). The Anti-enlightenment Tradition. Yale University Press. Pages 121, 125, 126. ISBN: 9780300135541

- ↑ Wistrich, R. S. (1989). The Jews of Vienna in the Age of Franz Joseph. Liverpool University Press. Page 206. ISBN: 9781909821880

- ↑ Fritze, R. H. (2022). Hope and Fear: Modern Myths, Conspiracy Theories and Pseudo History. Reaktion Books. Page 144. ISBN: 9781789145403

- ↑ Birken, Lawrence (1994). "Volkish Nationalism in Perspective". The History Teacher. 27 (2): 133–143. doi:10.2307/494715. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 494715.

- ↑ Field, G. G. (1981). Evangelist of Race: The Germanic Vision of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN:9780231048606

- ↑ Blamires, C., Jackson, P. (2006). World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 Volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing. Page 35. ISBN:9781576079416

- ↑ Hutton, C. (2005). Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Dialectic of Volk. Polity Press. Page 177. ISBN:9780745631776

- ↑ The Nazification of an Academic Discipline: Folklore in the Third Reich. (1994). Indiana University Press. Page 100.

- ↑ Bownas, J. L. (2018). The Myth of the Modern Hero: Changing Perceptions of Heroism. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN:9781845199029

- ↑ Rabinowitz, B. (2023). Defensive Nationalism: Explaining the Rise of Populism and Fascism in the 21st Century. Oxford University Press. Page 167. ISBN:9780197672037

- ↑ Mosse, G. L. (2021). The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. University of Wisconsin Press. Chapter: "Ideological Foundations". ISBN: 9780299332044

- ↑ Staudenmaier, P. (2014). Between Occultism and Nazism: Anthroposophy and the Politics of Race in the Fascist Era. Brill. Chapter 2. ISBN: 9789004270152

- ↑ The Global Impact of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion: A Century-Old Myth. (2012). Taylor & Francis. Page 4. ISBN: 9781136706103

- ↑ Krebs, C. B. (2011). A Most Dangerous Book: Tacitus's Germania from the Roman Empire to the Third Reich. W. W. Norton. ISBN: 9780393062960

- ↑ Fritze, R. H. (2022). Hope and Fear: Modern Myths, Conspiracy Theories and Pseudo History. Reaktion Books. Page 155. ISBN:9781789145403

- ↑ François, S. (2023). Nazi Occultism: Between the SS and Esotericism. Taylor & Francis. ISBN:9781000840049

- ↑ Austrian manifestations were surveyed by Rudolf G. Ardelt, Zwischen Demoktratie und Faschismus: Deutschnationales Gedankengut in Österreich, 1919–1930 (Vienna and Salzburg) 1972 (not translated into English)

- ↑ Heidi Paris and Peter Gente (1982). Monte Verita: A Mountain for Minorities. Translated by Hedwig Pachter, Semiotext, the German Issue IV(2):1.

- ↑ Guinness, Jonathan (2015). The House of Mitford. Orion. ISBN 9781474603188.

- ↑ Stefan Breuer: Die Völkischen in Deutschland. Darmstadt 2008, Page. 147. ISBN: 9783534213542 (in German)

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 François, Stéphane (2009). "Qu'est ce que la Révolution Conservatrice ?". Fragments sur les Temps Présents (in français). Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ↑ Ustorf, W. (2000). Sailing on the Next Tide: Missions, Missiology, and the Third Reich. P. Lang.

- ↑ Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus: Eine Beziehungs- und Konfliktgeschichte. (2012). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN: 9783647369969 (in German)

- ↑ Wilhelm Stapel, "Das Elementare in der völkischen Bewegung", Deutsches Volkstum, 5 May 1924, pp. 213–15.

- ↑ S. Schindelmeiser: Geschichte der Baltia, Bd. 2, München 2010. Page 233. ISBN: 978-3-00-028704-6

- ↑ Uwe Lohalm: Völkischer Radikalismus. Die Geschichte des Deutschvölkischen Schutz- und Trutz-Bundes 1919–1923, Hamburg 1970; Hermann Wilhelm: Dichter, Denker, Fememörder. Rechtsradikalismus und Antisemitismus in München von der Jahrhundertwende bis 1921, Berlin 1989.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: 1889-1936: Hubris. New York: Norton (1998)

- ↑ Werner Jochmann: Nationalsozialismus und Revolution : Ursprung und Geschichte der NSDAP in Hamburg 1922 - 1933. Dokumente. Europäische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg 1963, pg. 25.

- ↑ Lepage, J. G. (2009). Hitler Youth, 1922-1945: An Illustrated History. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. 16-17. ISBN:9780786452811

- ↑ Levy, R. S. (2005). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. ABC-CLIO. Page 743.

- ↑ Mühlberger, D. (2004). Hitler's Voice: Organisation & development of the Nazi Party. P. Lang. Page 231-280.

- ↑ Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische. "Artgemeinschaft". bpb.de (in Deutsch). Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ↑ Stefanie von Schnurbein: Göttertrost in Wendezeiten. Neugermanisches Heidentum zwischen New Age und Rechtsradikalismus. Munich 1993, Pg. 46. (in German)

- ↑ Gasper, Müller, Valentin: Lexikon der Sekten, Sondergruppen und Weltanschauungen. Verlag Herder, Freiburg 1990. (in German)

- ↑ Kaplan, Jeffrey (1997). Radical Religion in America: Millenarian Movements from the Far Right to the Children of Noah. Syracuse: Syracuse Academic Press. Page 78 .ISBN 978-0-8156-0396-2.

- ↑ Gardell, Matthias (2003). Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Durham and London: Duke University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8223-3071-4.

- ↑ Stefanie von Schnurbein: Kontinuität durch Dichtung – Moderne Fantasyromane als Mediatoren völkisch-religiöser Denkmuster. In: Uwe Puschner u. G. Ulrich Großmann: Völkisch und national. Darmstadt 2009, Page 284. (in German)

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Gardell, M. (2003). Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Duke University Press. ISBN: 9780822384502

- ↑ Contemporary Esotericism. (2014). Taylor & Francis. Page 244. ISBN:9781317543572

- ↑ Medievalism and Metal Music Studies: Throwing Down the Gauntlet. (2019). Emerald Publishing Limited. Page 75. ISBN:9781787563957

- ↑ Revisiting the "Nazi Occult": Histories, Realities, Legacies. (2015). Camden House. Pages 14, 279 & 292 ISBN:9781571139061.

- ↑ Petry will den Begriff „völkisch“ positiv besetzen, Die Welt vom 11. September 2016

- ↑ Frauke Petry wirbt für den Begriff „völkisch“, Die Zeit, 11. September 2016

- Fascism

- Ableism

- Anti-intellectualism

- Authoritarianism

- Conservatism

- Culture

- Eugenics supporters

- Far-right politics

- Imperialism

- Nationalism

- Political terms

- Racism

- Xenophobia

- Political philosophies

- Political theory

- Right-wing politics

- Right-wing activists

- Homophobia

- Nazism

- Purity culture

- Sexism

- Totalitarianism

- World War II

- White supremacy