George Wallace

| God, guns, and freedom U.S. Politics |

| Starting arguments over Thanksgiving dinner |

| Persons of interest |

“”I tried to talk about good roads and good schools and all these things that have been part of my career, and nobody listened. And then I began talking about niggers, and they stomped the floor.

|

| —Attributed in George Wallace: Settin' the Woods on Fire |

George Wallace (1919—1998) a.k.a. the Hangman "The Fighting Little Judge", was governor of Alabama for (sigh) four terms, two of them non-consecutive: 1963-1967, 1971-1975, 1975-1979, and 1983-1987. He was also the "#1 assistant" of his wife, the governor from 1967-1968. Every Governor from Alabama is a racist, but Wallace was something worse; he just played a racist on TV. More people should study his story as a cautionary tale about the depths people will sink to in order to win office.

According to the Drive-By Truckers, George Wallace is now in paradise, partyin' it up Alabama-style with the good Lord.

Governor of Alabama[edit]

The thing you have to understand about Wallace was that before he was elected, he was a racial moderate or even liberal. As a judge, he was known for his leniency toward black defendants. Most other judges threw the book at them for even minor infractions, so this was a relatively huge deal back in those days. He was well respected for it among blacks.

Wallace's first run for governor was actually in '58. He ran on a platform of chasing the Klan out of Alabama. Wallace had the backing of the NAACP that year.

His opponent in the Democratic Party primary was the pro-KKK John Patterson. (The Democratic primary was for all intents and purposes the general election, as with most other southern states at the time.) Wallace refocused his platform on things like economics and infrastructure. He lost the election — and not by a little bit. This is from one of his speeches during that race:

And I want to tell the good people of this state, as a judge of the third judicial circuit, if I didn’t have what it took to treat a man fair, regardless of his color, then I don’t have what it takes to be the governor of your great state.

Oops. Lesson learned. Wallace knew what he had to do to win the Alabama election: do a 180 on the segregation issue, which he did. He spoke to his finance director after the results and let slip the real reason![]() for his conversion.

for his conversion.

He proceeded to get elected on a pro-segregation platform in '63, and shortly after that gave his infamous first inaugural address ("I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny and I say segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!") and his equally-infamous "stand in the schoolhouse door" proclamation.

Barring segregation, Wallace's record as governor was mixed. He did provide funds to help rebuild Alabama's crumbling infrastructure, rebuild schools, raise teachers' salaries, and make welfare benefits more accessible, at least to whites.[1]:265 However, he also abused his position to accept government kickbacks and used Al Lingo's State police to harass and intimidate political opponents.

In 1966, Alabama's state constitution prohibited governors from serving two consecutive terms. Wallace had tried to repeal this law as governor but failed. Eventually, his hunger for office led him to urge his wife, Lurleen, to run for the governorship. Lurleen, who was arguably more beloved than her hubby in Alabama, easily won the election. In 1961, she was diagnosed with uterine cancer; she was kept in the dark about this for 4 years so her husband could cling to that mahogany desk. In 1968, during the middle of her governorship, the cancer killed her.

Presidential candidate[edit]

In 1964, Wallace ran an abortive challenge against President Lyndon Johnson in several Democratic primaries. Wallace proved competitive even in northern states like Wisconsin,[2] channeling working-class resentment towards minorities, civil rights, and liberalism. Most of Wallace's supporters backed Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, who lost to Johnson in a landslide (but also won several states in the deep South; the first Republican to do so post-Reconstruction).

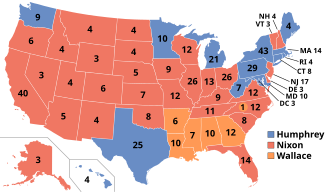

In 1968, Wallace ran for President of the United States on the American Independent Party ticket, a cobbled-together party of Birchers, southern segregationists, and elderly mental cases (two of those are redundant). He knew he wouldn't win, but he did hope to play kingmaker and force whoever won to back down from civil rights-related reform. Wallace channeled resentment against racial and antiwar unrest. "We don't have any riots in Alabama," he proclaimed: "They start a riot down there, first one of 'em to pick up a brick gets a bullet in the brain."[1]:367 Thus Wallace endeared himself to segregationist Democrats not yet ready to take the plunge towards the Republican Party. While Wallace's attempts to play kingmaker failed, the fact he tried and the numbers showed his success was enough for the American government to seriously consider changing their electoral system and removing the Electoral College. They came close to doing so, with plans with changing to the two-round system France had with it failing due to a handful of Senators.

Wallace's equally colorful running mate was Curtis LeMay, former Air Force general and model for Dr. Strangelove's General Ripper. LeMay bested his fictional counterpart by criticizing the American "phobia" towards nuclear weapons at a press conference in Pittsburgh. He described Bikini Atoll's recovery from nuclear tests; while land crabs were "a little hot... the rats...are bigger, fatter and healthier than they ever were before."[1]:359 LeMay was Robert McNamara's![]() old boss. LeMay taught McNamara, who was Kennedy and Johnson's Vietnam War-era Defense Secretary, the delicate art of "carpet-bombing" over Tokyo in the 1940s.[3] Where Kennedy, Johnson, & McNamara fucked up, LeMay, the expert, was finally gonna set straight over North Vietnam. Ironically, LeMay evinced pro-choice and pro-environment positions that troubled Wallace's base more than his endorsement of nuclear holocaust.

old boss. LeMay taught McNamara, who was Kennedy and Johnson's Vietnam War-era Defense Secretary, the delicate art of "carpet-bombing" over Tokyo in the 1940s.[3] Where Kennedy, Johnson, & McNamara fucked up, LeMay, the expert, was finally gonna set straight over North Vietnam. Ironically, LeMay evinced pro-choice and pro-environment positions that troubled Wallace's base more than his endorsement of nuclear holocaust.

Despite these missteps, Wallace did surprisingly well. He won 13.5% of the popular vote and five Southern states, making him the last third party candidate to win any electoral votes.

Later career[edit]

Wallace returned to the Democratic Party and the governor's seat by 1971. He defeated sitting governor Albert Brewer in a remarkably dirty runoff election, even by Alabama standards. Besides sabotaging his opponent's campaign rallies, Wallace distributed literature showing a white girl menaced by black men, captioned This Could Be Alabama Four Years From Now! Do You Want It? He was equally unsubtle in person, telling supporters "If I don't win, the niggers are going to control this state."[1]:391-5

Wallace subsequently ran for President again in 1972 and 1976, modulating his more overt racism as a defense of states' rights. In 1972 an assassination attempt on his life cut his campaign short, though he did win two major northern primaries in a sympathy vote right after he was shot. In 1976 he was still popular enough to win several primaries, though Jimmy Carter, another Southern Governor, undercut his popularity in that region.

Wallace eventually flip-flopped a second time on the segregation issue, recanting his former racist ways and winning the 1982 gubernatorial election with unprecedented record levels of black support after granting pardons in the infamous decades-old Scottsboro Boys![]() case. While apologetic for his segregationist stance in later years, Wallace's sincerity remains the source of heated debate.[4]

case. While apologetic for his segregationist stance in later years, Wallace's sincerity remains the source of heated debate.[4]

See also[edit]

- Martin Luther King assassination conspiracies

- Donald Trump - Another far-right demagogue associated with working class whites leaving the Democratic Party.

- Strom Thurmond - An older Dixiecrat who made a third party run.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Carter, Dan T. (1995). The politics of rage: George Wallace, the origins of the new conservatism, and the transformation of American politics. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80916-8.

- ↑ The Adamany study of Cross-Over Voting and the Democratic Party's Reform Rules found that in 1964, 62% of the 26% of crossover voters in the Wisconsin Democratic primary voted for Wallace; in 1972, 29% of the 34% of crossovers voted for Wallace and concluded that "the participation of crossover voters will . . . alter the composition of national convention delegations." U.S. Supreme Court, Democratic Party v. Wisconsin ex rel. La Follette, 450 U.S. 107 (1981).

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cdmfPThGZ-s

- ↑ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/daily/sept98/wallace090591.htm