Astrobiology

| It's not rocket science, it's... Astronomy |

| The Final Frontier |

| The abyss stares back |

| Live, reproduce, die Biology |

| Life as we know it |

| Divide and multiply |

| Great Apes |

Astrobiology, exobiology or occasionally xenobiology is the speculative science of extraterrestrial life.[note 1] Despite being entirely speculative, it still plays an important role in such arenas as the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) or ET life in general.

Assumptions about life[edit]

Astrobiologists have to tread a fine line between assuming that some commonalities we observe in life on Earth will be required elsewhere, and still working with the limitations that the chemistry and physics of the Universe impose on possible biologies. For instance, there is no reason to expect that life elsewhere would be based on DNA or protein structures like ours. However, a way of transmitting information from one generation to another is a vital component for what we define as "life". Whatever the alien equivalent to DNA might be, it would probably have similar features, such as a polymeric structure and an auto-catalytic copying mechanism based on hydrogen bonding (or other bonding perhaps), but not the exact same molecular structure. It is also considered that temperatures and pressures leading to the presence of liquid water are key factors, due to water's role as a very flexible polar solvent and its general abundance in the universe, though other solvents like liquid ammonia, methane, or carbon dioxide have been suggested.[1]

When considering the chemistry of potential extraterrestrial life, it is also highly likely that molecules with carbon or hydrocarbon structures will form a vital part of the picture, due to carbon's ability to form many kinds of molecular bonds, thus forming the basis of huge numbers of potential chemical processes. When people involved in projects like SETI want to know "what to look for" in order to have a good idea of "where to look", they turn to astrobiologists to try to improve their odds.

Rocky planets[edit]

Some rocky planets, such as Earth, are capable of supporting carbon-based "life as we know it". Conditions necessary for life are generally thought to be:

- Orbit around a yellow star (like the Sun), a red dwarf, or a stable combination of those stars. Stars redder than the sun may also be life sustaining, as may stars slightly hotter.[2]

- Presence of water, carbon and other organic elements. This is believed to be fairly common, at least on planets that formed around stars with a decent level of heavy element enrichment — astronomers call this "metallicity" (in astronomy all elements heavier than helium[note 2] are called "metals").

- Presence of water, and carbon-based organic molecules. The former is believed to be fairly common, around the third most common compound in the universe after molecular hydrogen and carbon monoxide, while higher-resolution spectroscopy equipment has started to detect fairly large organic molecules - for example Saturn's moon Enceladus has organic compounds at least 300 Daltons in size.

- Orbit within the habitable zone (distance from star where the temperatures allow water to exist as liquid water). Estimates range from anywhere around 1.1 to 0.53 times Earth's insolation, to 1.5 to 0.5 times Earth's insolation.

- Presence of an active core that causes volcanic and tectonic activity as well as a magnetic field to protect the surface from cosmic and solar radiation (life evolving despite this is perhaps possible but probably far more difficult). It is thought that at most, the dividing mass line for geological activity is 0.815 Earth masses, similar to the mass of Venus.

- The size and density of the planet have to be such that the planet's gravity can hold an atmosphere, but is not so strong as to crush lifeforms.

- The planet's solar system resides in the habitable zone of its galaxy, thus avoiding extreme galactic radiation and gravitational tides. This criterion is debated, but in any case it does not exactly matter for nearby (relatively speaking) exoplanets.

In our Solar System, Mars is the only planet (besides Earth of course) to meet these criteria even remotely. Allegedly, the majority of scientists at a conference hosted by the European Space Agency believe Mars has, or used to have, life[3] (naturally, the latter is more likely). As for exoplanets, several such as HD 40307 g, Teegarden's Star b, and K2-18 b probably meet these criteria. That being said, current methods for detecting exoplanets are biased towards finding ones that aren't Earth-like - favoring close, high-mass planets.

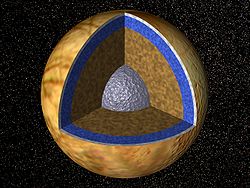

Europa, one of Jupiter's satellites, is too cold to support life on its surface, but likely has life in subsurface liquid oceans (the Europa Clipper spacecraft launched recently is en route to investigate it more thoroughly). Ganymede, Enceladus, Triton, and perhaps some other satellites of the gas and ice giants could also harbor subsurface oceans. Titan, a satellite of Saturn, is likewise too cold for liquid water, but has the right surface conditions for liquid methane and ethane, and could hypothetically support life that uses methane as a working fluid.

Habitable zone[edit]

The Goldilocks Zone, Habitable Zone, or Life Zone is the relatively narrow range of distance from a star within which an orbiting planet (or in some cases a planet's moons) may be able to sustain life, at least the carbon-based forms we know and love, because the temperature is right for water to remain liquid.[4] Water is a common enough material in the universe and acts as a very flexible biochemical solvent. The phrase "Goldilocks Zone" is a reference to the story of Goldilocks and the Three Beers Bears, since, like the porridge which Goldilocks chose to eat in the bears' house, conditions in the Goldilocks Zone are neither "too hot" nor "too cold", but are "just right". The definition of a Goldilocks Zone has expanded to include moons such as Enceladus that exist within a zone where warming occurs through tidal friction by their planet (Saturn, in the case of Enceladus), as opposed to external heating by a star, thus expanding a lot the places where water-based life could appear.[5].

In our solar system, the inner edge of the zone lies between the orbits of Venus and Earth, while the outer edge extends roughly as far as the pericenter of Mars, i.e. its closest point to the Sun. The habitable zone changes as the stellar activity of the star system evolves - in the case of our Sun, its luminosity increases by 1% roughly every 100 million years. Earth is the only Goldilocks planet in our own solar system, although admittedly Venus was in the habitable zone for up to 950 million years after the Sun's formation before a runaway greenhouse effect turned it into a dead world. Non-Goldilocks temperatures also correspond with differences in the physical geology and chemical composition of the environment - inner objects like Mercury have less volatiles (water, nitrogen, methane, etc.) while outer objects like Pluto have more.

Significance[edit]

Identifying other habitable or inhabited planets is a major preoccupation in space exploration and colonisation, as well as a perennial theme in science fiction. The most compelling reason for this fascination with Goldilocks planets is the possibility that they could already support extraterrestrial life, which is arguably the Holy Grail of space exploration. It has now become possible to spectroscopically analyze atmospheres and determine densities of planets (giving us a good idea on their composition) although definitive biosignature detection is still rather speculative - anyways, we could discover species unknown on Earth, and studying the development of life elsewhere could provide new insights into such aspects of biology as the origin of life and the degree of chance involved in evolution. The discovery of Goldilocks zone planets attracts interest from the media and the public as well as the scientific community. 22% of stars like our sun may have Goldilocks planets similar to Earth according to data from the Kepler telescope.[6]

Exceptions[edit]

We must remember not to limit ourselves to searching for life on Earth-like planets inside habitable zones, as alternative scenarios have been proposed, such as volcanic activity providing heat on planets or moons outside of the habitable zone (similar to "smokers" on Earth's ocean floors), silicon-based life that can survive where carbon-based life cannot, and even floating, balloon-like lifeforms living in the atmospheres of gas giants. Other forms of life unknown to scientists today may have evolved elsewhere in the Universe to thrive in conditions that are not Goldilocks at all. Of course, there is also the downside that these forms life might be so radically different from anything we consider to be "life" that we may not even be able to recognize it as such.

Insufficiency[edit]

Many other factors are also required to make a planet suitable for life. Atmospheric composition is one, as the greenhouse effect can either raise the temperature enough to keep surface water liquid, or make it too hot for liquid water, and the mass of the planet is also important for maintaining this atmosphere. Planets that are too small do not have sufficient gravity to hold on to their atmospheres in the face of the onslaught of the solar wind.

The range of the Goldilocks Zone also changes throughout a star's lifespan, slowly edging out further away from the star as it ages. Therefore a planet needs to remain inside the zone as it drifts outward. This favours planets which form just on the outer edge of the zone early in a solar system's life, as the zone will then spread outwards slowly as the star ages and heats up. A good example is Earth, which originally was on the outer edge and now may rest closer into the inner edge.

Carbon-based life[edit]

All known life on Earth is "carbon-based", which means that the most important atom in the molecules that compose life is carbon. One of the simplest reasons for why carbon is the most important atom in biology is its chemical properties and how they react.

Carbon is able to form long chains, as well as more complex structures, cyclic rings, aromatic rings and polycyclic systems such as steroids. This gives rise to an entire discipline, organic chemistry, devoted to the study of carbon-based molecules. The reason for this is the unique structure of the carbon atom: carbon has 4 electrons on its outer shell and because carbon, like every other atom, tries[note 3] to attain the most stable configuration, which is an outer shell which is effectively "full". So, by a fairly unremarkable quirk of quantum mechanics and thermodynamics, carbon will bond with up to four other atoms, such as hydrogen, oxygen, or nitrogen.

Carbon is not the only atom with this bonding structure: silicon is very similar to carbon (it is the next element down from carbon in the periodic table, and so has the same valence structure, but with another shell of electrons under it) and although it binds less readily than carbon, some bacteria are known to incorporate silicate structures in their physiology. Silicon-based life, however, is highly unlikely, as large silicate structures become unstable, don't display the diversity of organic compounds, and silicon dioxide, the product of respiration, is solid in standard conditions. However, it is worthwhile to consider that complex silicon chemistry could thrive in a "goldilocks zone" distinct from that calculated for carbon-based chemistry, i.e. different temperatures and pressures such that silicon dioxide is a gas etc. as opposed to the solid it exists as in a carbon goldilocks zone. In the absence of chemical evidence to suggest it can form appropriate structures, "silicon-based" life remains a pipe dream of science fiction writers. So, barring anything truly spectacularly different, any life "as we know it" will almost certainly be carbon-based.[note 4] In 2016, scientists were able to genetically engineer a bacterial enzyme that can incorporate silicon into basic organic molecules, although true silicon-based life is still a long, long way off.[7]

Exceptions[edit]

The above assumptions have some interesting exceptions, which may suggest a greater possibility of extraterrestrial life.

Extremophiles[edit]

No, we're not talking about kinky folks, we're talking about any number of microscopic organisms that have adapted to live in what we would consider extreme environments here on Earth. There have been documented findings of life in places formerly believed inhospitable, such as thermal vents on the ocean floor, extremely hot or cold water, high or low pressure environments, highly acidic or alkaline environments, up to 3.6 km underground,[8] inside rocks,[note 5] and in locations without oxygen.[9] Sometimes entire ecosystems have been discovered based on these critters.

For example, Strain 121![]() can survive at temperatures of 121°C, and Colwellia marinimaniae

can survive at temperatures of 121°C, and Colwellia marinimaniae![]() can grow at pressures of 120 megapascal.

can grow at pressures of 120 megapascal.

One of the key factors about extremophiles on thermal vents is the rapidity with which these vents are colonised. While such colonies are hardly evidence of a second genesis on Earth, they do show that life, as it is, can thrive in very unusual circumstances. Importantly, many deep sea extremophiles can survive without the help of the Sun's energy, so the first trophic level in such ecosystems is not photosynthesising plants, but bacteria that use the heat and reactive chemicals from the vents to provide chemical energy. This is particularly key to the potential existence for life on planets in the outer Solar System, where the solar flux from the sun is greatly reduced.

Extremophiles indicate that life can thrive in places that common sense would tell us should be barren and devoid of life. The discovery of these organisms in the 1970s led biologists to believe life could possibly exist in similar environments on planets (or moons) that were previously thought to be inhospitable. Because of the conditions that we have actually observed life thriving in, it is certainly not impossible for bacterial life to still be present on Mars, particularly in the polar regions where there is ice and potentially liquid water, or extremely cold places such as asteroids. One of the other prime candidates for life within the solar system are the oceans that are suspected to be under the ice on Europa, one of Jupiter's moons. While it is widely accepted that Europa is theoretically capable of hosting bacterial life (and until a probe is sent to successfully dig under it, we will be unable to confirm this idea), some recent theories have led to the idea that cosmic rays may be capable of oxygenating underwater oceans to similar levels found on Earth, thus macroscopic life may also be a very realistic possibility.[10]

Elliptical orbits[edit]

A planet in our location but orbiting the Sun in a much wider ellipse would dip in and out of the Goldilocks Zone during its orbit, and so possibly could not sustain life. Some scientists speculate that life may be able to survive on planets with elliptical orbits that take them out of the habitable zone from time to time. All that may be required is liquid water at some point in a planet's orbit. Life could hibernate during cold conditions or could shelter in watery places during hot conditions.[11]

On the other hand, if a planet has an eccentric orbit but stays within the habitable zone for the entire time, it probably does have habitable temperatures as well.

Plasma life forms[edit]

Experiments have showed that in some conditions, blobs of plasma can grow, replicate and communicate.[12] Also according to computer simulation, it is possible for interstellar clouds of spacial dust to store information, since dust particles could join together to form double-helix structures similar to DNA and can even divide to create two identical copies of the same structure.[13][14]

Boltzmann brains[edit]

In statistical mechanics and quantum mechanics, anything can pop out of vacuum energy by random thermal or quantum fluctuation given enough time. Theoretically speaking, it is possible that a conscious entity (i.e., a Boltzmann brain) could be formed from such random fluctuations given enough time in two ways: either a quantum fluctuation, in which case the brain would appear together with an equivalent amount of antimatter![]() and would have just enough time for a single thought before being annihilated back into the vacuum[15] or a thermal one, also brought into existence in the case of an Universe dominated by a cosmological constant as ours seems to be by particles emitted by the cosmological horizon[15]. In this case, the brain would last much longer, until it cooled down, died, and decayed away, but would live in a dead and dark Universe. Life would probably be extremely dull for such a being, maybe even outright hellish, unless it came with a surrounding world formed in the same way to support its existence for a time at least.

and would have just enough time for a single thought before being annihilated back into the vacuum[15] or a thermal one, also brought into existence in the case of an Universe dominated by a cosmological constant as ours seems to be by particles emitted by the cosmological horizon[15]. In this case, the brain would last much longer, until it cooled down, died, and decayed away, but would live in a dead and dark Universe. Life would probably be extremely dull for such a being, maybe even outright hellish, unless it came with a surrounding world formed in the same way to support its existence for a time at least.

The probability of this occurring is ridiculously small,[16][17][18] moreso in the case of Boltzmann brains of the second kind and way more unlikely if they came with support systems to extend their lives as a body, a planet and an energy-giving star, etc. too. However, over an infinite time span, the probability of this (up to entire galaxies being assembled such way) happening is not only plausible, but inevitable. The timing for this happening is incomprehensibly long, however, and when the first Boltzmann brains start appearing the universe would have long since undergone heat death![]() and they may well be the final forms of life in the Universe.

and they may well be the final forms of life in the Universe.

Boltzmann brains of the second type (as the first ones are self-contained and would last too little to be a worry) are also a serious problem with cosmologists, given that over an infinite time an infinite number of them would come and go outnumbering normal observers that had not come into existence in such way, thus the likelihood of us being actually Boltzmann brains existing alone in a vacuum with false memories being extremely high.[19] The consensus, however, is that such calculations are actually wrong[20], and there's also the possibility of either no Boltzmann brains of the second kind being able to form (i.e. dark energy dissipating away so no cosmological horizon radiating away particles that would assemble them) or the Universe dying away long before they had time to come into existence.

Artificial life[edit]

With our own teetering steps into artificial life just beginning, one should not make the mistake of assuming that all alien life is organic in origin.

The universe may well contain numerous genetically engineered and/or mechanical civilisations which have either superseded or outlasted their creators. They may also have capabilities that organic life does not, or have incredibly long lifespans and massive intelligence. Such beings might be capable of traveling between stars for centuries or millennia without dying. Additionally, it might be possible for ETs to cheat death by uploading themselves onto machines, although the feasibility of such practices is not looking too good.

Scope of astrobiology[edit]

Given all this, the question becomes "how much life is out there?" Given the relative ease of communicating versus travelling to other planets, the more relevant question may be "how much life out there could we talk to?" The Drake Equation attempts to provide the framework of an answer. Of course, the chance of communicating with an intelligent civilization becomes vanishingly small with distance.

Religious reactions[edit]

Creationist[edit]

Some creationists outright deny the existence of extraterrestrial life, because the Bible doesn't explicitly mention it. However, in the Book of Job there is mention of a council that is held with the sons of God. It has been thought that these "sons" are the leaders of other created civilizations, but since there was no concept for extraterrestrials at the time the Bible was written, it far more likely refers to either angels or other deities in the time Judaism was a polytheistic religion instead. There are those that believe that if life were found on another planet, it would most likely be very simple, not fully-formed advanced organisms created instantaneously, like in the Genesis story. As such, they argue that life on Earth is very, very, very finely tuned to exist, and probably doesn't anywhere else. But these people don't take into account that our God is a creator and He will keep on creating.

Catholic[edit]

Although the Catholic Church does not require its members to be creationists, Church officials have weighed in on the issue of extraterrestrial life. When the exoplanet 51 Pegasi b![]() was discovered in 1995, one bishop proclaimed that if any life existed on said world, it would have souls in need of salvation. (51 Pegasi b is a "hot Jupiter", and if any lifelike critters existed in its atmosphere, they wouldn't resemble life as we know it.) A cardinal[Who?] was quick to denounce this claim, however, saying that they didn't know if original sin occurred on other worlds. Jesuit members of the Vatican Observatory have made slightly more informed

was discovered in 1995, one bishop proclaimed that if any life existed on said world, it would have souls in need of salvation. (51 Pegasi b is a "hot Jupiter", and if any lifelike critters existed in its atmosphere, they wouldn't resemble life as we know it.) A cardinal[Who?] was quick to denounce this claim, however, saying that they didn't know if original sin occurred on other worlds. Jesuit members of the Vatican Observatory have made slightly more informed decisions assumptions regarding the souls of extraterrestrial life.[21]

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Seti.org

- Astrobiology Magazine

- Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight, David Darling

Notes[edit]

- ↑ However, some definitions of astrobiology include the study of such things as how plants grow in zero-G, which has some level of actual testing.

- ↑ And thus not dating back to primordial nucleosynthesis but to nuclear reactions within stars, with the exception of lithium

- ↑ This does not mean it "tries" in the sense that people make conscious efforts to attain goals. It means that in the state alluded to, (the absolute value of) the binding energy (the sum of the kinetic energy and potential energy) is lowest — the carbon atom is effectively "rolling downhill" when it forms bonds that fill these shells. Note that by convention potential energy and binding energy have negative signs.

- ↑ The more so as any hypothetical silicon-based life is extremely unlikely to arise and survive in any environment that fosters carbon-based life. For one thing, it would require a significantly different regime of liquid medium, pressure, temperature, and chemical availability; for another, its prognosis in any hypothesised competition against carbon-based life is quite poor owing to carbon's greater elemental abundance, the greater stability of its compounds, and its lower energy requirements for building complex structures (causing greater rapidity of replication, mutation, and evolution).

- ↑ Think of the Horta, albeit on the bacterial level

References[edit]

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20061012144717/http://www.clearleadinc.com/site/extraterrestrial-life.html

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Habitability of red dwarf systems.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Extraterrestrial life § Direct search.

- ↑ Are we not the only Earth out there?

- ↑ To the outermost regions of the Solar System

- ↑ 22% of Sun-like Stars have Earth-sized Planets in the Habitable Zone

- ↑ Researchers take small step toward silicon-based life, Robert F. Service, Science 18 March 2016

- ↑ New "Devil Worm" Is Deepest-Living Animal: Species evolved to withstand heat and crushing pressure by Dave Mosher, National Geographic News, June 2, 2011.

- ↑ ScienceShot: Animals That Live Without Oxygen 7 April 2010

- ↑ Universe Today - Europa Capable of Supporting Life

- ↑ NASA: Extreme forms of life can survive on planets with weird orbits

- ↑ http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn4174-plasma-blobs-hint-at-new-form-of-life.html#.U8sfg7HIwfw

- ↑ http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19526174.500-life-in-interstellar-dust.html

- ↑ http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/news/2007/aug/15/helices-swirl-in-space-dust-simulations

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Matthew Davenport and Ken D. Olum, Are there Boltzmann brains in the vacuum? Institute of Cosmology, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Tufts University, Medford, MA, 4 August 2010.

- ↑ Mason Inman, Spooks in space. New Scientist, 15 August 2007.

- ↑ Andrei Linde, Sinks in the Landscape, Boltzmann Brains, and the Cosmological Constant Problem. Department of Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 28 January 2007.

- ↑ Andrew Zimmerman Jones, What Is the Boltzmann Brains Hypothesis? thoughtco.com, 14 April 2018.

- ↑ Anil Ananthaswamy, Universes that spawn 'cosmic brains' should go on the scrapheap. New Scientist, 15 February 2017.

- ↑ Sean M. Carroll, Why Boltzmann Brains Are Bad. Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, 6 February 2017.

- ↑ Claire Giangravè, Could Catholicism handle the discovery of extraterrestrial life? cruxnow.com, 24 February 2017.