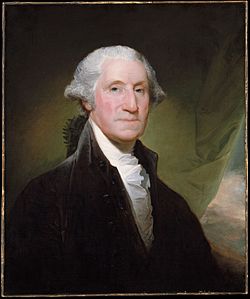

George Washington

“”Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. I... carry with me the hope that my country will never cease to view them with indulgence; and that, after forty five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.

|

| —George Washington's farewell address, 19th September, 1796.[1] |

| God, guns, and freedom U.S. Politics |

| Starting arguments over Thanksgiving dinner |

| Persons of interest |

George Washington (1732–1799), also known as Agent 711[2] was the first President of the United States (served 1789 to 1797). Before that, he was the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, as well as a freemason, a slave-owner, and likely a deist. For his role in militarily defending the American Revolution and doing much to shape the office of the presidency, Washington is today the most famous Founding Father of the United States, even earning the title of "Father of His Country."[3]

Born in Virginia and serving many years with the Virginia Regiment, Washington became a delegate to the Continental Congress before being sent to lead American armies against the British Empire. During the war, Washington endured hardship in the loss of New York City and Long Island and the harsh winter retreat at Valley Forge. Much of his survival during this period is attributable to his espionage network, a system he functionally invented and used to negate British battlefield advantages.[4] In 1778, France came to save the day, and Washington led allied troops to victory in the 1781 Siege of Yorktown. That battle led to a peace agreement in 1783, and Washington soon resigned his commission and went home.

Washington's interest in politics arose again due to the political catastrophes caused by the Articles of Confederation, finally agreeing to attend the Constitutional Convention of 1787. During the proceedings, Washington's status as a national hero made it clear that he would be the first American president under the Constitution. In 1788, Washington won unanimous election from the Electoral College, and he repeated that feat in 1792 making him the only President to do so.[note 1]

During his presidency Washington struggled to deal with the United States' financial problems, a rebellion in Pennsylvania, and the American Indian Wars. America also lost its ally during the French Revolution, as knowledge of the US' military weakness pushed Washington to declare neutrality in the ensuing European wars. He retired after the end of his second term for personal reasons, helping to set a two-term precedent.

Like many other Founding Fathers and early presidents of the United States, Washington's legacy is heavily marred by the institution of slavery, which he protected while in office despite his personal misgivings.

Early life[edit]

Washington was born in Virginia to an extremely wealthy family, which had originated in England and made a fortune in the colonies by owning a large number of tobacco-producing slave plantations.[6]

The first president's childhood years are the source of one of the most persistent myths about him. The story goes that the six year-old Washington received a hatchet as a gift and damaged his father’s cherry tree and then chose to confess to his father on the basis that "I cannot tell a lie".[7] This story was a complete fabrication by biographer Mason Locke Weems, who aimed to teach moral lessons rather than actual history.[8][note 2] Other persistent myths appear throughout Washington's life, all inflicted upon American memory by Weems.

Virginia militia[edit]

Washington joined the Virginia militia at a time when the British Empire was competing heatedly with France over control of the Ohio region.[10] Washington also played a significant role in gaining an alliance with the Iroquois Confederacy against the French through diplomacy.[11] As you'll soon see, Washington was a much more capable politician and diplomat than soldier.

In 1754, colonial tensions escalated into war, and Washington commanded the opening engagement, the Battle of Jumonville Glen. Washington attacked French forces with his command and his Indian allies, resulting in many of the French being killed including a simple diplomatic messenger.[12] The French were infuriated at what they considered to be a dishonorable attack.

The British gathered their forces at Fort Necessity in what is now Pennsylvania. The French and their Indian allies attacked, and Washington was forced to surrender the fort. In doing so, he also (probably due to poor translation) signed a document acknowledging his responsibility for murdering the French diplomatic envoy.[13] The amusing thing is that Washington's great defeat came on July 3rd, 1754.[14] His withdrawal from the fort came on July 4th.

Washington suffered another defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela due to disorganization, and Washington's commanding officer Edward Braddock died in the combat.[15] After suffering a friendly fire incident and another failure in the Forbes Expedition, Washington experienced humiliation at the hands of other British officers and resigned his commission in disgust.[16]

On the one hand, Washington won precisely zero major engagements, but on the other his forces did successfully defend the Virginia frontier.[17] Additionally, many of Washington's failures were due to the inherent disorganization of the colonial militia system, which left him with a strong belief in the necessity of centralized government.

Civilian life[edit]

Greedy plantation owner[edit]

In 1759, Washington married Martha Custis, a widow a year older than himself, as he was attracted to her intelligence and ability to manage plantation household affairs.[18] Custis was herself a wealthy woman with a large amount of land, and the marriage thus turned Washington into one of the wealthiest men in Virginia.

Washington was far from a paragon of virtue. Instead, he was greedy and ambitious. He bought, sold and traded slaves, often dividing families in order to ensure a nice profit.[19] Washington owned slaves starting at the age of eleven, and his total number of slaves was over three hundred at the time of his death.[20] Washington also cheated his own militiamen out of land. You see, to encourage people to join the war against the French, the British had promised land to the militiamen after it was done. Washington ensured that his pal got to be in charge of parceling out that land when all was said and done, meaning that his 52 enlisted men got 400 acres each while Washington got 18,500 acres, nearly as much as all the enlisted men combined.[19] He then tricked some of his officers into selling their shares of land by claiming that the royal government might cheat them, getting his personal share up to more than 27,000 acres. When one of Washington’s fellow officers, Major George Muse, complained to him directly, Washington wrote back a furious reply calling Muse "stupid", "ungrateful", "dirty", and accusing him of "drunkenness."[21] What a bastard.

Political activities[edit]

In 1758, Washington won election to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he promptly proceeded to do nothing really exciting with his legislative power.[22] The experience did, however, leave Washington with enhanced knowledge of politics.

During his political career, Washington came to resent the British Parliament for trying to impose heavier taxes on the colonies, and he even denounced the post-Boston Tea Party punitive acts as an attempt to make the colonists slaves just like the blacks.[23] Washington played a role in shaping the Fairfax Resolves, a Virginia document rejecting Parliament's claims of supremacy over the colonies and calling for the formation of a colonial congress.[24] Washington then became a delegate to the First Continental Congress, but he mostly spent his time training Virginia militia and enforcing a boycott on British goods.[25] Washington returned to the Continental Congress after receiving word of the outbreak of war in 1775.

Revolutionary War[edit]

Commander-in-Chief[edit]

The Continental Congress formed the Continental Army to resist the British and then appointed George Washington to be its Commander-in-Chief. They chose Washington primarily because of his previous military experience, as while it might not have been brilliant, it did give Washington experience in fighting in the American wilderness. Washington had been nominated for the position by John Adams.[26]

Stance on torture of prisoners of war[edit]

During the Revolutionary War, American patriots were declared traitors and thus were not eligible for prisoner of war treatment, meaning that they were usually neglected and mistreated.[27] Many more Americans died from disease and malnutrition in imprisonment than from battle.[28]

After capturing over 1,000 Hessian soldiers in the Battle of Trenton, George Washington was asked how to deal with prisoners of war, with American patriots weary of how the British had been treating their comrades. In his orders, Washington said, "Treat them with humanity, and let them have no reason to Complain of our Copying the brutal example of the British Army in their treatment of our unfortunate brethren… Provide everything necessary for them on the road."[29]

Agent 711 and the Culper Ring[edit]

Washington has also been dubbed "America's first spymaster" since he began the new nation's very first espionage operation to help win the war against the British.[30] This operation was called the Culper Ring, which collected vital intelligence from the British while operating in occupied New York City.[31]

This was a notable innovation, as espionage at the time was viewed as "ungentlemanly" and unworthy of effort.[32] However, the spy agency was entirely necessary, since any hope of defeating such a superior foe relied on knowing how that foe would conduct its operations. Washington himself had a direct role in espionage, being known as "Agent 711" by the Culper operatives.[33] Due to compartmentalization, Washington also often didn't know about many of the ring's operatives and operations. Some procedures were pretty sophisticated, like communicating through coded laundry hanging, using dead drops, and placing double agents to work within the British administration.[33] The ring was quite successful, helping to root out Benedict Arnold, discover a plot to counterfeit America's currency, and foiling a plan by the British to sneak attack the French before they could arrive.[33]

The Culper Ring was mostly financed by Washington himself out-of-pocket, although he was eventually reimbursed by Congress to the tune of $17,000—nearly half a million dollars in today's money.[32]

Early defeats[edit]

The early stages of the war went poorly for Washington. Much of that wasn't Washington's fault though, since Congress ordered an invasion of Quebec, and General Benedict Arnold pulled troops from Washington's force to make that happen.[34] That weakened Washington considerably right ahead of the Siege of Boston, which just barely ended in an American victory.

The British struck back, though, seizing New York City by pulling off a flank attack that caused Washington's troops to panic.[35] Washington made up for it by managing the incredible feat of evacuating his army out of Long Island, thus avoiding a siege. After several more defeats, the Continental Army had to retreat into Pennsylvania. Washington did manage to get a another shot in by secretly crossing the Delaware River with his forces on Christmas to launch a surprise attack against British mercenaries.[36] Still, that was a relatively minor victory in the fact of the fact that the Continental Army had basically no supplies and was stranded in Loyalist territory.[37]

Washington was then outmaneuvered at the Battle of Brandywine in mid-1777, allowing the British to capture the American capital of Philadelphia.[38] That winter marked the what was likely Washington's darkest hour. His army took shelter in Valley Forge near occupied Philadelphia, but the winter was harsh and food and supplies ran low.[39]

Gates conspiracy[edit]

After a demoralizing winter at Valley Forge, news arrived that France had joined the war on America's side. In autumn 1777, General Horatio Gates had won the Battle of Saratoga in northern New York, a victory which convinced France to aid the Americans against the longtime French enemy the British Empire.[40] The news came in May 1778, a few weeks before Washington's departure from Valley Forge, and French officer the Marquis de Lafayette helped train and revitalize Washington's army.[39]

It was still significant that it was Gates who had won Saratoga rather than Washington. General Gates became extraordinarily popular, and he used that popularity to attempt to replace Washington as the leader of the Continental Army.[41] Playing on Washington's failures, especially at the Brandywine, Gates and fellow conspirator Brigadier General Thomas Conway plotted Washington's political downfall.[42] The plan was only foiled by the drunken boasting of conspirator James Wilkinson, which gave Washington notice and eventually embarrassed the conspirators enough to stop. Washington's subordinate generals supported him, and Gates and Conway denied that they had done anything.

France to the rescue[edit]

“”The general to whom His Majesty intrusts the command of his troops should always and in all cases be under the command of General Washington... The French troops, being only auxiliaries, should on this account... yield precedence and the right to the American troops.

|

| —Louis XVI instructions to Rochambeau.[43] |

Washington was thrilled to hear that the French were coming, though, and his army greeted the news by shouting the amusingly non-republican "Long Live the King of France!"[44] French General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau arrived in Rhode Island with more than 5,000 French soldiers, and he quickly became friends with Washington despite speaking almost no English.[44] The two men were an effective team, and they began crucial steps towards winning the war. Elsewhere, French navies and soldiers attacked British colonies around the world, forcing the Empire to divert precious resources away from the American theatre. Spain also joined in on the fun with French encouragement, causing more headaches for the British.

The final great victory was famously the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. This was actually a French plan from Admiral François Joseph Paul de Grasse, who realized that the French fleet could blockade British troops in the port city.[43] Washington also delegated much command responsibility to Rochambeau, who was a noted siege specialist in France.[43] It was the French who brought it home at Yorktown, and Washington made sure to express his gratitude in his letter to headquarters.[45]

Resignation[edit]

After the British withdrawal from America, Washington decided to get one last greedy act in by charging the Continental Congress with a bill of $450,000 in expenses, including some suspicious items like reimbursing his wife's travel expenses.[46] Man's gotta make ends.

In December of 1783, Washington then resigned his commission in a ceremony in which he tried to make it as clear as possible that America's supreme military leader was subordinate to Congress.[47] The resignation also reflected Washington's desire to fuck off back to Mount Vernon and live like just any other fabulously rich plantation slave-owner.

Constitutional crisis[edit]

Renewed political involvement[edit]

Washington's self-imposed exile didn't last too long before he got sucked back into the fray again. The Articles of Confederation, designed hastily in wartime, proved totally unable to cope with the needs of modern governance. Washington had been skeptical of them from the beginning, feeling that a central government was necessary to ensure military readiness. He would know. In 1785, he expressed his feelings on the matter to Henry Knox, denouncing the articles as a "rope of sand" failing to bind the American states together.[48]

Matters came to a head in 1786 when Massachusetts farmers revolted under the leadership of disgruntled war veteran Daniel Shays.[49] The rebellion began because Massachusetts was unable to pay its debts to war veterans. It became apparent that the Articles of Confederation had prevented the national government from being able to manage its own finances, leading to the financial crisis that had brought so many farmers to the point of desperation. Washington was personally convinced by the event that a new constitution was needed urgently.

Constitutional Convention of 1787[edit]

Washington was initially reluctant to attend the convention, but other members convinced him that his presence would add legitimacy to the proceedings and attract more delegates.[50] The meeting occurred in secret, and Washington's role was to mostly sit there silently in his military uniform and occasionally cast votes for or against certain articles.[51] He wanted to avoid coming off as a partisan hack.

Washington's support of the final product was ultimately vital to ensure ratification.[52]

Presidency[edit]

1788 election[edit]

Washington was pretty clearly the favored choice to be the first US president, so much so that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention considered it a done deal.[53] Turnout was pretty low, but Washington won the entire Electoral College with no real opponents, while John Adams beat several other candidates to be Washington's VP.[54]

Shaping the office[edit]

The US Congress created the first executive departments, and Washington immediately but innocently overstepped the bounds of the Constitution by having the department heads serve as his Cabinet.[55] Washington presided over Cabinet debates without doing much to interfere, instead allowing his cabinet members to fight it out. This helped develop the fierce rivalry between Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and State Secretary Thomas Jefferson, most notably over the issue of national credit and debt. Washington tended to support Hamilton on financial issues, which Jefferson wasn't happy about.[56]

Economics[edit]

Washington's first term was mostly focused on economics, as the US still had ridiculous amounts of wartime debt, and the financial problems that had sparked Shay's Rebellion were still unresolved. Hamilton had his financial plan ready, but faced strong opposition from Jefferson and the anti-Federalists who opposed what they perceived as government overstep on the rights of the states. The two men eventually agreed to the Compromise of 1790, in which Jefferson would support allowing the federal government to assume state debts in exchange for moving the national capital to the District of Columbia near Jefferson's home state of Virginia.[57] Poor Abraham Lincoln would have reason to be unhappy about this decision some decades later.

Slave acts[edit]

“”Absconded from the household of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair.

|

| —1796 fugitive slave ad posted by the Washington household.[58] |

From the very beginning, there were tensions between the more abolitionist north and the slave-holding south, especially now that they had less power to manage their own affairs. Washington appeased the South by signing the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which intended to resolve a dispute between Pennsylvania and Virginia over the kidnapping of a black man in Pennsylvania by three Virginians.[59] The act made it a crime for anyone to assist an escaped slave, and it legalized slave hunting in free states. Washington himself had cause to use the act, posting an ad to pursue escaped slave Oney Judge, making the poor woman an outlaw for the rest of her life.[60]

The Fugitive Slave Act became an essential pillar of the slave regime in the United States, and fugitive slave ads were numerous until the end of the Civil War.[61] It was eventually replaced by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which was even harsher.

On the less shitty side, Washington signed the Slave Trade Act of 1794, which outlawed the importation of slaves into the United States, thus ending American involvement with the Atlantic Slave Trade.[62] The act remained enforced, and its penalties actually steadily increased as the US government came to consider slave trading from overseas to be a form of piracy.[63]

Whiskey Rebellion[edit]

George Washington had established federal authority, but in 1794, he was abruptly forced to defend it. Rural Pennsylvanians got antsy when the federal government imposed a tax on the whiskey they produced, claiming that rural Pennsylvania was underrepresented in Congress.[64] Protests soon became violent as they resisted the tax, escalating to the point where officials were tarred and feathered. (Tarring and feathering usually involves hot pitch, and was thus quite painful).[65]

Alexander Hamilton advocated for a military crackdown, but Washington instead readied militia and led about 13,000 troops on a slow march into western Pennsylvania.[66] The warning ultimately worked, and the rebellion collapsed by the time Washington got there. Two Pennsylvania men were captured and sentenced to be hanged for treason, but Washington invoked the first-ever use of the presidential pardon to let them off.[67] This also proved to be another source of fury in the Hamilton-Jefferson feud, as Jefferson was sympathetic to the rural Pennsylvanians in this ordeal and didn't appreciate Hamilton advocating for military force against them.[note 3]

All in all, Washington's quick action demonstrated the federal government's ability to enforce its laws without necessarily relying on the use of force. This was crucial to ensuring the stability of the US constitutional order.

Britain and France[edit]

Washington's major foreign policy conundrum ended up being the French Revolution. The French expected American support for obvious reasons, but when they sent citizens to raise cash and lobby for the French cause, Washington denounced them and demanded that the effort be shut down.[69]

The French were further alienated when Washington approved the Jay Treaty, even though in hindsight it was a necessary decision. The Jay Treaty settled some longstanding hostilities between the US and the UK, with the British ending sanctions against the US and evacuating the Ohio Territory and the US agreed to pay debts and open the Mississippi River to British trade.[70] Still, the Treaty left many things out since the US had few bargaining chips, and it proved very unpopular with the US public and barely squeezed through the US Senate.[71] Jefferson, who had always favored the French and even got to spend half a decade in the nation while cheering on its revolution that were described as "among the happiest years of his life,"[72] was furious that the US would cozy up to an enemy of a revolutionary state.

The French were also quite pissed that they had been betrayed by Washington, and they announced that they would seize American ships in the Atlantic to help their own war efforts.[73] That decision, though, would be more John Adams' problem, since it came shortly before Washington decided to retire.

American Indian Wars[edit]

Typically of Americans, Washington was an expansionist. While Washington hoped to obtain land peacefully from Native Americans, he wasn't above resorting to brutality if it came to that. Washington frequently sent militia expeditions to destroy native villages and farmland whenever they resisted US expansionism.[74] The British made this process a headache, though, since they armed the Native Americans with modern weaponry and encouraged them to harass and attack American colonists.[75]

Still, Washington was also a diplomat, and he regarded the more powerful and "civilized" tribes as legitimate foreign nations. Washington notably signed the Treaty of New York with the Creek, where in exchange for land, the US promised to keep colonists away from the Creek heartland, grant the Creek trade rights, and even grant their chief a salaried position within the US military.[76] Sadly, it "failed to achieve its goals, as the federal government could not stem the relentless incursion of American settlers onto 'protected' Indian lands."[77]

In the "bad" category, Washington also signed the unequal Treaty of Fort McIntosh with the native Western Confederacy, which was rejected by most of the tribes because it carved out an Indian reservation and opened about 2/3 of the Northwest Territory to US colonization.[78] The Western Confederacy was a major power, too, consisting of many tribes, including the Wyandot, the Miami, the Shawnee, the Lenape, the Potawatomi, the Ottawa, the Wabash Confederacy, Illini Confederacy, and the remnants of the Iroquois.[79] Kentucky militia attacked first, and they behaved atrociously by burning towns in the region that were both friendly and non-friendly.[80]

When hostilities escalated in 1790, Washington ordered General Josiah Harmar and a federal militia force into the Northwest Territory to destroy the Western Confederacy. Most of the battles that ensued were Native American victories, which were extremely humiliating to the US.[81] Washington then ordered Major General Arthur St. Clair, the military governor of the Northwest Territory, to launch a more vigorous offensive in 1791, which ended in a military disaster so severe that Congress actually launched its first-ever investigation into the doings of the executive branch.[82] Eventually, Washington decided to take the war seriously, and a professional military with artillery pieces managed to end the war in 1795. Not exactly a feather in Washington's cap, that affair.

Reelection[edit]

In the 1792 elections, George Washington was once again unanimously selected by the Electoral College. Washington didn't even want to run, since he was disgusted by the infighting of his cabinet and the growing inevitability that political parties would emerge.[83] When Washington openly considered retirement, his cabinet members dropped their political differences and begged him not to, as they knew that Washington's hero status was the only thing holding them all together.

Thus, Washington's unanimous reelection only served to hide the growing political rifts in the early United States. North and South already hated each other, and political factions were forming around the rivalry between Jefferson and Hamilton.[84] The vote for VP even made this clear. While Washington was the clear choice for president, John Adams only carried his home region of New England, while the rest of the states either voted for Thomas Jefferson or George Clinton.[84]

[edit]

Washington's second term began with threats from Barbary pirates, most notably from the region that is now Algeria. The United States economy, such as it was at the time, relied on shipping cash crops out to Europe, and the Mediterranean Sea became a kill box for pirates who preyed upon the new nation's undefended ships.[85] In response, Congress passed and Washington signed the Naval Act of 1794, which authorized funds for constructing six frigates to form the "don't fuck with us" backbone of what was to become the United States Navy.[86]

Probably the most famous of these ships is the USS Constitution. We're using present-tense for her because the USS Constitution is actually still a commissioned vessel with the US Navy, and crews still operate her to serve as a museum display ship.[87] After her construction, the Constitution fought against the French revolutionaries and the Barbary Pirates, becoming known as "Old Ironsides".

Retirement and Farewell Address[edit]

“”The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

|

| —George Washington's warning against partisanship and cults of personality in his Farewell Address.[88] |

Washington's retirement after two terms was more personal than political. He fell ill twice during his presidency, first with a tumor on his leg that had to be operated on in 1789 and then with a very severe flu in 1790.[89] It's thus quite understandable that Washington wasn't up for more of the strains of the presidency.

On the occasion of his retirement, Washington delivered his "Farewell Address", which received heavy input from Alexander Hamilton.[90] In it, he stressed that national unity was paramount to the survival of the republic, and he warned against the dangers of partisanship, regionalism, and foreign entanglements. Sadly, this message has been forgotten by the politicians of today. The Farewell Address was even received poorly by some of Washington's contemporaries, like James Madison, who considered it to be pro-Federalist.[91]

Post-presidency[edit]

Washington didn't live terribly long after the end of his second term, as he had been afflicted with numerous health problems throughout his presidency and life. Contrary to legend, Washington didn't fuck off to Mount Vernon to lie low and die. He took an active interest in the politics of the land. His concerns actually ring quite familiar to modern Americans, such as a rising partisan press and accusations of fake news, an attempt by a foreign power (in this case France) to meddle in US elections, and growing hatred between political parties.[92]

Washington's successor, the Federalist John Adams, violated the Constitution to name Washington Commander-in-chief of the US military despite the fact that Washington was an old man who didn't even want the post.[93] Washington also started to reveal his political opinions in public, writing that he distrusted the Democratic-Republican Party and fully supported Adams' infamous Alien and Sedition Acts.[94] No longer beholden to him, Jefferson and Madison retaliated by condemning Washington as a wannabe king.

Washington died in December of 1799 from a throat infection, easily treatable today but deadly back then, and the poor man basically suffocated to death in his own bed.[93]

Washington's slaves[edit]

Washington owned 317 enslaved human beings, a little more than half of whom were inherited from his marriage to his wealthy wife.[20]

Conditions in Mount Vernon[edit]

Washington's plantation, Mount Vernon, was sadly typical of slave plantations of the era in the ways slaves were treated. Washington employed overseers to squeeze work out of his slaves, and while Washington believed that rewards were more effective than punishment, punishment was still definitely on the table.[95] In 1793, overseer Anthony Whitting accused Charlotte, an enslaved seamstress, of being "impudent" and whipped her with a hickory switch, a reprisal Washington deemed "very proper".[95]

Washington could also threaten to demote house slaves to field work, a much worse position, or even sell slaves away from their friends and families into the much harsher Caribbean slave trade.[96] Washington did both of those things on at least several occasions.

The Washingtons relied on enslaved butlers, cooks, waiters, and housemaids to support their daily meals and frequent dinner parties.[97] House slaves would stand silently at the edges of the dining room to refill wine glasses or pass serving dishes as needed, and they would clear the table after the Washingtons were finished.[97]

Washington's records contain evidence that many of his slaves tried to resist his authority by doing things like intentionally breaking tools, pretending to be sick, or stealing food.[95] At least 47 enslaved people tried to run away from Mount Vernon, with the largest flight occurring in 1781 when 17 men and women escaped to the British warship Savage while it was anchored in the Potomac near Mount Vernon.[95]

William Lee[edit]

Washington also had a slave with him throughout the war. William Lee was a slave who Washington purchased from Mary Lee, a wealthy Virginia widow, for £61.15.[98] He acted as General George Washington's personal manservant throughout the war, responsible for grooming horses, preparing his Washington's clothing and equipment, delivering messages, and attending to other of Washington's personal needs.[99]

The friendship between Washington and Lee contributed significantly to Washington's changing views towards slavery, which he eventually came to regard as abhorrent.[98] There were a number of causes that changed Washington's mind, but being confronted with the undeniable humanity of a black man for many years undoubtedly helped this process along.

Changing views[edit]

After the war, Washington became uneasy with the institution of slavery and questioned the impact it would have on his new nation going forward. Throughout the 1780s and 1790s, Washington stated privately that he no longer wanted to be a slaveowner and didn't like separating families.[100] He also came to support a plan of gradual abolition. These changing views were also motivated by economics. Amid falling profits, it soon became clear to him that the costs of clothing and housing slaves wasn't worth the labor he got from them, and switching to less labor-intensive means of production meant that he had more slaves than he knew what to do with.[100]

Unfortunately, Washington never made these convictions public. He was convinced that a debate on slavery would destroy the United States in its cradle, and he also believed that the US needed the financial benefits of slavery to recover from the costs of the war.[100]

Ultimately, Washington's only good act on slavery was using his will to free the 123 slaves he owned personally. Sadly, this caused great pain since his slaves had intermarried with his wife's slaves, and his wife's slaves could not legally be freed by his will.[101]

Washington's religion[edit]

“”The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship... May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.

|

| —Washington's address to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island.[102] |

It's somewhat difficult to pin down Washington's exact religious beliefs, leading many modern Americans (especially religious conservatives) to make shit up about him. This is mostly because Washington was a very private man when it came to religion, often praying by himself and failing to participate in religious ceremonies.[103] Thomas Jefferson once noted an occasion where members of the clergy asked Washington a series of questions, slipping in one about his religious beliefs, in hopes of finally learning his theological views, only for him to totally ignore the question without comment.[104] Although officially an Anglican, Washington didn't seem too enthusiastic about public worship and was even scolded by the assistant rector of Christ Church in Philadelphia for leaving services early.[103] Still, this probably doesn't say too much about his personal beliefs, as it was certainly important for him to avoid seeming to beholden to a singular religion. He wanted to unite the colonies, not divide them.

There is still a fair bit of evidence to support the idea that Washington was a deist, albeit an unusually faithful one. Washington never referred to God as "Jesus" or "Christ" in any of his private correspondence, instead preferring terms like "Providence".[105] Perhaps even closer to the mark would be the term "theistic rationalist", a set of beliefs which rejects most Biblical fluff but also upholds the importance of prayer.[105] That would explain the recorded instances of Washington praying alone.

Freedom of religion[edit]

Regardless of his personal beliefs, Washington was a very firm defender of religious liberty. This was an essential belief, too, since the colonies were quite religiously diverse thanks to the English practice of deporting heretics, and old instances of religious tension in the colonies had resulted in very bad things happening.[106] Washington made his goal of defending religious liberty quite clear, writing to the United Baptist Churches of Virginia in May of 1789,[107]

“”I beg you will be persuaded that no one would be more zealous than myself to establish effectual barriers against the horrors of spiritual tyranny, and every species of religious persecution—For you, doubtless, remember that I have often expressed my sentiment, that every man, conducting himself as a good citizen, and being accountable to God alone for his religious opinions, ought to be protected in worshipping the Deity according to the dictates of his own conscience.

|

Washington's support for religious liberty was not limited to Christians. He famously visited Touro synagogue and promised to protect the rights of Jews to practice their religion without fear of persecution, a declaration that made him quite popular with the small Jewish communities around the United States.[108]

Basically, Washington was not at all like the version of him portrayed in the art of Jon McNaughton.

Legacy[edit]

Pseudohistory[edit]

Only a few months after his death, Washington was the subject of his first biography, a hagiography by Mason Locke Weems that went into several editions and reprints, and promoted a mythology around Washington based on the author's ideas of giving moral instructions to the nation.[109][110] A later edition of the book included the Weems' lie that Washington actually said, "I cannot tell a lie, I did it with my little hatchet".[109] Lying to promote morality — that doesn't sound very moral.

Other inventions from Weems included a story about Washington praying at Valley Forge,[8] which was apparently intended to be a moral story about the strength of religious conviction.

Monument[edit]

Washington is famously remembered by the towering Washington monument in the District of Columbia, which was also named in his honor as Washington, DC. In 1833, the Washington National Monument Society was founded by Chief Justice John Marshall and former president James Madison, and they gradually collected donations to begin construction in 1848.[111] It was only completed in 1885, after the project had run out of money multiple times and had to be saved by the government. Its apex is made of aluminum, which at the time was quite rare and valuable,[112] and at 555 feet tall, at the time it was the tallest building ever built. Then the French one-up'd the entire US by building the Eiffel Tower and discovering how to make cheap aluminum, both within just 2 years.

There are also a shitload of statues and parks in Washington's honor as well as a few other less famous memorials and a nice handful of universities. Wikipedia has a List of memorials to George Washington![]() if you happen to be interested for some reason.

if you happen to be interested for some reason.

US currency and stamps[edit]

Washington is also portrayed on US currency and postage stamps, moreso than any other figure. Paper currency first appeared in the US during the American Civil War, and the Bureau of Engraving and Printing quickly decided to put Washington's face on the most widely-used bill.[113] Washington also appears on the $1 coin[114] and the quarter.[115] He's also featured on US postage stamps, way too many to count.

Badass Japanese action hero[edit]

Washington was also the source of some amusing anecdotes made up by Japan, whose population became extremely fascinated with American history after its forcibly opening by the Perry Expedition. Since Japanese writers knew almost nothing about the Americans, they filled the demand by making up and illustrating exciting anecdotes and metaphors about American figures, like John Adams fighting a giant serpent with a katana and George Washington fighting off three men with a katana.[116] This is the badass George Washington we wish we got.

And because this is just too much fun not to include here, there's also a story where Washington defends his wife "Carol" from the evil British while a jacked as fuck Benjamin Franklin helps him by lifting a whole-ass cannon onto his shoulder and firing it.[117] And finally, Washington wins the war against the British by beating the shit out of a random tiger with his bare hands.[116]

As awesome as this all was, it's important to note that it was basically fanfiction that wasn't intended to be taken seriously. Author and illustrator Nozaki Bunzō had made a name for himself as a writer of amusingly awesome historical fiction, and he described himself as a "Scribbler of Foolish Words".[116]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Although James Monroe ran unopposed in 1820, one faithless Elector casted a vote for John Quincy Adams.[5]

- ↑ Although, humorously, he introduced the story in his book on George Washington by calling it "too true to be doubted."[9]

- ↑ Jefferson would go on to repeal the Whiskey tax while President.[68]

References[edit]

- ↑ Transcript of President George Washington's Farewell Address (1796).

- ↑ George (Agent 711) Washington, and Others. Washington Post.

- ↑ Father of His Country Mount Vernon

- ↑ The importance of spies to Washington’s success. Army University Press.

- ↑ United States presidential election of 1820 Britannica

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Washington family.

- ↑ Cherry Tree Myth. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Parson Weems. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ CHAPTER II: BIRTH AND EDUCATION The Life of Washington

- ↑ Anderson, Fred (2007). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-3074-2539-3. p. 31–32

- ↑ Ferling. (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-6081-9182-6. p. 15–16

- ↑ Chernow (2010). Washington: A Life. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-266-7. pp. 42–43

- ↑ Fort Necessity. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle of Fort Necessity.

- ↑ The Braddock Campaign. National Park Service.

- ↑ Lengel, Edward G. (2005). General George Washington: A Military Life. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6081-8. p. 75–76

- ↑ Ellis, Joseph J. (2004). His Excellency: George Washington. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4031-5. p. 38

- ↑ Wiencek, Henry (2003). An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-17526-9. p. 69

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 George Washington’s Moral Metamorphosis. History Net.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 10 Facts About Washington & Slavery Mount Vernon

- ↑ From George Washington to George Muse, 29 January 1774. National Archives.

- ↑ Virginia House of Burgesses. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Alden, John R. (1996). George Washington, a Biography. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2126-9. p. 101.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Fairfax Resolves.

- ↑ Ford, Worthington Chauncey; Hunt, Gaillard; Fitzpatrick, John Clement (1904). Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789: 1774. 1. U.S. Government Printing Office. v. 19, p. 11.

- ↑ George Washington: The Commander In Chief. UShistory.org

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Prisoners of war in the American Revolutionary War § American prisoners.

- ↑ Burrows, Edwin G. (2008). Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners During the Revolutionary War. Basic Books, New York. ISBN 978-0-465-00835-3. p. 64.

- ↑ Washington's Crossing, Page 379.

- ↑ Nagy, John A. (2016). George Washington's Secret Spy War: The Making of America's First Spymaster. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-2500-9682-1. p. 274.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Culper Ring.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 The Letter That Won the American Revolution. National Geographic.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 George Washington, Spymaster. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Taylor, Alan (2016). American Revolutions A Continental History, 1750–1804. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-35476-8. p. 151–153

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle of Long Island.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River.

- ↑ Ketchum, Richard M. (1999) [1973]. The Winter Soldiers: The Battles for Trenton and Princeton. Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6098-0. p. 235

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle of Brandywine.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Winter at Valley Forge. American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battles of Saratoga.

- ↑ Battle of Saratoga. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Conway Cabal. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Few Want to Admit It, but the French Saved America During the Revolution. History News Network.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 How France Helped Win the American Revolution. American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ From George Washington to Thomas McKean, 19 October 1781. National Archives.

- ↑ Alden, John R. (1996). George Washington, a Biography. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2126-9. p. 209

- ↑ Resignation of Military Commission. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ From George Washington to Henry Knox, 28 February 1785. National Archives.

- ↑ Shays' Rebellion of 1786. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ Chernow. (2010). Washington: A Life. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-266-7. , pp. 220–221

- ↑ Constitutional Convention. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Presiding Over the Convention: The Indispensable Man. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Alden, John R. (1996). George Washington, a Biography. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2126-9. p. 226–27

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on 1788–89 United States presidential election.

- ↑ Cooke, Jacob E. (2002). "George Washington". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed.). Scribner. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-684-31226-2. p. 4–5

- ↑ Cooke, Jacob E. (2002). "George Washington". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed.). Scribner. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-684-31226-2.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Compromise of 1790.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Gazette and Universal Daily Advertiser, May 24, 1796 [Oney Judge runaway notice].

- ↑ Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 Facts. American History Central.

- ↑ Oney Judge. UShistory.org

- ↑ RUNAWAY! How George Washington, Other Slave Owners Used Newspapers to Hunt Escaped Slaves. Library of Congress.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Slave Trade Act of 1794.

- ↑ The African Slave Trade. National Archives.

- ↑ Whiskey Rebellion. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Tarred and Feathered. Today I found Out.

- ↑ The Whiskey Rebellion. PBS.

- ↑ The First Presidential Pardon Pitted Alexander Hamilton Against George Washington. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ Whiskey Rebellion Mount Vernon

- ↑ Elkins, Stanley M.; McKitrick, Eric (1995) [1993]. The Age of Federalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509381-0. p. 335–54

- ↑ Jay Treaty. Britannica.

- ↑ John Jay’s Treaty, 1794–95. US State Department

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson as an American in Paris, Revisited Governing

- ↑ Akers, Charles W. (2002). "John Adams". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed.). Scribner. pp. 23–38. ISBN 978-0-684-31226-2.

- ↑ Calloway, Colin G. (2018). The Indian World of George Washington. The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1906-5216-6. p. 38

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, John C. (1936). "Washington, George". In Dumas Malone (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography. 19. Scribner. pp. 509–527.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Treaty of New York (1790).

- ↑ Native American Policy Mount Vernon

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Treaty of Fort McIntosh.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Western Confederacy.

- ↑ Sword, Wiley (1985). President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790–1795. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2488-1. p. 35–36

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Harmar campaign.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on St. Clair's defeat.

- ↑ Randall, Willard Sterne (1997). George Washington: A Life. Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-2779-2. p. 484.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Presidential Election of 1792. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ U.S. Navy. National Parks Service.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Naval Act of 1794.

- ↑ USS Constitution. National Parks Service.

- ↑ Washington's Farewell Address 1796.

- ↑ George Washington's Health. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Hayes, Kevin J. (2017). George Washington, A Life in Books. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190456672. p. 287–298.

- ↑ Spalding, Matthew; Garrity, Patrick J. (1996). A Sacred Union of Citizens: George Washington's Farewell Address and the American Character. Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8476-8262-1. p. 143

- ↑ The Myth of George Washington’s Post-Presidency. Politico.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 George Washington's turbulent retirement. CBS News.

- ↑ Washington and the Republicans. Digital History.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 95.3 Resistance and Punishment. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Slave Control. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Labor in the Mansion. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 William (Billy) Lee. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ William "Billy" Lee. American Battlefield Trust.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 Washington’s Changing Views on Slavery. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ George Washington's Will. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ From George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, 18 August 1790. National Archives.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 George Washington and Religion. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ Notes on a Conversation with Benjamin Rush, 1 February 1800 Founders Online

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 George Washington's Religious Beliefs/Faith. GeorgeWashington.org

- ↑ Religious Freedom. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ From George Washington to the United Baptist Churches of Virginia, May 1789. National Archives.

- ↑ Touro Synagogue. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 See the Wikipedia article on Mason Locke Weems.

- ↑ A History, of the Life and Death, virtues, and Exploits of General George Washington by Mason Locke Weems (1800) John Bioren.

- ↑ Washington Monument Construction Timeline. National Parks Service.

- ↑ George J. Binczewski (1995). "The Point of a Monument: A History of the Aluminum Cap of the Washington Monument". JOM. 47 (11): 20–25. doi:10.1007/bf03221302. S2CID 111724924.

- ↑ How George Ended Up on the $1 Bill. Lives and legacies.

- ↑ George Washington Presidential $1 Coin. US Mint.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Quarter (United States coin).

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 116.2 Japanese George Washington-The Bare Handed Tiger Slayer. War History Online.

- ↑ Osanaetoki Bankokubanashi :19th C Japanese Fanfic History of America. Rough Diplomacy.