Nudity

| The high school yearbook of society Sociology |

| Memorable cliques |

| Most likely to succeed |

| Class projects |

Nudity is the state of a human being entirely without clothes (naked) or lacking the proper body covering considered normal in a particular social situation (undressed). Human nakedness is a biological fact but nudity is only understood in a cultural context. The cultural context for nudity did not exist until humans began living in communities large enough to develop hierarchies of status and class, and religious beliefs regarding clothing the body. Before clothing, people decorated their bodies to show tribal membership, prosperity, marital status, and individuality.[2]

Among ancient cultures, only members of the Abrahamic religions associated nudity with shame regarding sexuality, while in other cultures being naked was a loss of status and dignity, an embarrassment but not deeply shameful.[3] The Genesis myth, with its misunderstanding of human nature and sexuality, continues to influence or dominate the attitudes and behaviors regarding nudity in most of the world. In addition to the human body being shameful, scripture asserts male domination as fundamental to moral behavior.[4] The societies that have become more secular are also those that have freed themselves from shame regarding the human body and have more gender equality as in Finland,[5] Germany,[6] and The Netherlands.[7]

Evolution of nakedness and clothing[edit]

The loss of body hair, along with increasing brain size and upright posture, was part of the evolution of hominids into anatomically modern humans.[8] While there have been a number of theories explaining the human loss of fur, the most generally accepted one is thermal regulation of the body. Cooling was required when hominins moved from shady forest to open savannah. An increase in the number of sweat glands, and sweat drying on bare skin, provided cooling during the day, fire was used to keep warm at night. Thermal regulation was related to the increasing size of the brain, the most heat-sensitive organ.[9][10] Hair on top of the head was retained, providing shade during the day and insulation at night.[11]:265-270 No longer having fur, the first humans developed dark skin as protection from the Sun.[12][13][14] In addition to carrying weapons and tools, bipedalism became adaptive in part due to babies no longer having fur to cling to, so mothers had to carry them.[15]

Body adornments, including jewelry, body paint, and tattoos are indications of the beginning of human behavioral modernity in the late Paleolithic (40,000 to 60,000 years ago).[16] Although there is no consensus on a definition of behavioral modernity, four sets of behaviors are included; abstract thinking, planning in depth, innovativeness, and symbolic representation.[17]

The habitual wearing of clothing has been dated to between 83,000 and 170,000 years ago by comparing the divergence of clothing lice from their body louse ancestors.[18] If anatomically modern humans first appeared 350,000 to 260,000 years ago, they were naked in prehistory for at least 90,000 years.[19] This means illustrations or films that show prehistoric humans as light-skinned and modestly dressed are distortions of reality.

The technology for making clothes evolved slowly, having originated for other purposes. Animal skins and woven mats used for sleeping became decorative when draped on the body, but might not cover the genitals.[20] Complex, fitted clothing needed to survive in cold climates required the invention of fine stone knives for cutting animal skins into specific shapes, and the eyed needle for sewing. Evidence has been found that this was done by Cro-Magnons in Europe around 35,000 years ago.[21]

Body adornments including clothing may serve to enhance rather than hide sexual attraction. The non-sexual, or functional nudity in everyday life is maintained by behavioral norms; including sitting or standing modestly and not staring at others. In modern sociology, these behaviors are called "civil inattention"![]() and serve to maintain personal boundaries even when naked.

and serve to maintain personal boundaries even when naked.

In ancient civilizations from Mesopotamia to the Roman Empire, gods and goddesses were depicted as perfect naked humans and nudity was part of some religious ceremonies. However, being nude in everyday life was often socially embarrassing, not due to sexuality but the lack of status.[22][note 1] Otherwise, being naked or undressed in social contexts where clothes were the norm meant being poor, being a slave, or doing labor that was hot, dirty or wet. The average person, both men and women, might own a single piece of cloth that would be wrapped or tied (e.g. a loincloth)![]() to cover the lower part of the body, but otherwise were bare-chested and barefoot. Only those of high status were habitually dressed[24], but even they would often be naked when bathing or swimming, which were social activities.[25] Children, having no status, might be naked until puberty.[25][26][27]

to cover the lower part of the body, but otherwise were bare-chested and barefoot. Only those of high status were habitually dressed[24], but even they would often be naked when bathing or swimming, which were social activities.[25] Children, having no status, might be naked until puberty.[25][26][27]

For the first millennium after the fall of Rome (approximately 500 to 1500 CE), the conversion of Europe to Christianity included conflicting interpretations of scripture and accommodations for existing social norms regarding the human body and sexuality. Groups emerged with beliefs as different as Adamites who worshiped nude, to ascetic monks who slept fully clothed.[28]:455-456 The predominant view of Medieval Christian theology was that sexuality and nudity were sinful except for procreation, which might include avoiding nudity even between spouses.[29] However, theology did not put an end to all behaviors that had been normal during the Roman era, in particular public communal bathing, which might be mixed-gender.[30][31]

The modern era begins in the Renaissance with the rediscovery of classical texts and art, which interacted with Abrahamic traditions to produce Western ambivalence, nudity acquiring both positive and negative meanings in individual psychology, in social life, and in depictions. The conservative versions of these religions continue to prohibit public and sometimes also private nudity.[32]:7

Nudity and Abrahamic religions[edit]

The Abrahamic religions all share the Genesis myth, which is ambivalent and contradictory. In Genesis 1:27 Adam and Eve are created together in the image of God, naked but unashamed.[note 2] In Genesis 2:21-22 Adam is created first, then Eve from Adam's rib. After "The Fall" in Genesis 3, Adam and Eve attempt to hide their nakedness from God (who sees everything anyway). This myth attempts to establish clothing as necessary for human moral conduct from just after the beginning, ignoring the period of naked innocence and that there was no social context for feeling shame.[34] Orthodox Judaism generally forbids complete nudity, at the most extreme even between spouses. In addition to misunderstanding human nature, Genesis places the responsibility for all immorality, beginning with the "original sin" of disobedience, on women.[4]:104-105

The body as something shameful became ambivalent in early Christianity. For the first centuries CE, baptisms were conducted nude[35] in the belief that converts were restored to the innocence of humans "before the fall". A group called the Adamites![]() in the 2nd century CE acted upon this interpretation by worshiping nude, but were suppressed as heretics.[36][37]

in the 2nd century CE acted upon this interpretation by worshiping nude, but were suppressed as heretics.[36][37]

The variation in early Christian behavior is likely due to early European converts being Romans who did not give up their public baths, which remained popular in the Carolingian Period.![]() It was only in later centuries, when converts came from Northern tribes living in climates that required warm clothing, that nudity became problematic. European pagans were nude in public only during fertility rituals, which they gave up after conversion. In the Medieval era, the theology of Thomas Aquinas and Augustine of Hippo defined sexual arousal, and thus nudity, as something to be avoided except for procreation.[29]

It was only in later centuries, when converts came from Northern tribes living in climates that required warm clothing, that nudity became problematic. European pagans were nude in public only during fertility rituals, which they gave up after conversion. In the Medieval era, the theology of Thomas Aquinas and Augustine of Hippo defined sexual arousal, and thus nudity, as something to be avoided except for procreation.[29]

Religious beliefs continued to determine behavior into the 20th century. English families in the 1920s to 1940s never saw other family-members undressed, including those of the same gender; and married couples were not nude even during sex.[38]

Nudity and witchcraft[edit]

Witches have been depicted nude![]() for a long time

for a long time![]() in visual arts

in visual arts because most books on witchcraft are written by men with the origin of this coming from stories from many cultures where they are thought to go such way in their gatherings at night.[39]. That was also mentioned in the book Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches![]() [40], jumping from it to Wicca and other forms of Neopaganism and modern witchcraft as ritual nudity[41], with Robert Graves using the term "skyclad" to refer to it based on Indian religions

[40], jumping from it to Wicca and other forms of Neopaganism and modern witchcraft as ritual nudity[41], with Robert Graves using the term "skyclad" to refer to it based on Indian religions![]() , where the term Digambara

, where the term Digambara![]() means that[42].

means that[42].

Colonialism and racism[edit]

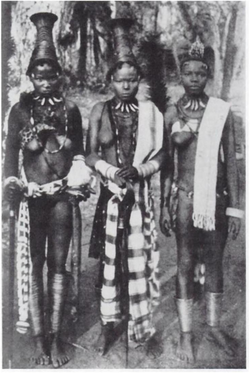

Technologies for navigation and transport in the 1500s led to contact with more distant parts of the world. By the 18th century European thought was embracing ideas such that social progress represented movement from primitive to agriculture to industrialization. Many Europeans justified colonization as spreading civilization rather than as conquest.[44] The lack of body coverings was one of the first things explorers noticed when they encountered indigenous peoples of the tropics. Europeans were concerned with explaining states of undress, which they did not see as a natural. For centuries, being properly dressed in Western cultures was required to fit into society. Explanation for the scanty dress or nudity of others was generally provided by religion.[45] An enduring stereotype of non-western others is the naked savage based upon the belief that clothes signified membership in a civilized society, thus the lack of clothes represented the complete lack of culture.[46]

Some indigenous peoples of the Americas, Asia, and Oceania have skin no darker than that of southern Europeans, or among workers tanned by the Sun, thus their nakedness was interpreted as being of low status. The darker skin and other superficial differences in African, Melanesian, and Australian peoples could be interpreted as their being less than human. Darker skin was also assumed to be dirty, however anthropologists have noted that many non-Western societies have elaborate rituals of bathing and purification.[45]

Contemporary cultural differences[edit]

While human societies vary widely in their way of life, all share common characteristics that are conceptualized as dimensions of culture.[47] Dimensions of culture as related to nudity include power distance — the degree to which people accept unequal power and privilege in society. Clothing became an important means of communicating status and wealth, thus historically nudity was a sign of being at the bottom of society, while certain clothing styles and colors were reserved for the ruling classes. Socialism initially adopted nudism as part of promoting equality, but split between democratic and authoritarian forms.[citation needed]

Intersecting with power is gender equality, the degree to which norms for women are more severe and restrictive than for men. Contemporary societies that score high in gender equality are also those with more positive attitudes towards sexuality and non-sexual social nudity; as seen in Iceland, Scandinavia, Finland, and The Netherlands.[48] These positive attitudes are attributed by some to sauna culture, which normalizes non-sexual nudity in the context of relaxation and purported health claims.[7]

Although maintaining sexual propriety is the primary reason given for avoiding nudity, maintaining the hierarchy of power and gender is an underlying motivation. Participants in the counterculture of the 1960s practiced nudity as part of their daily routine and to emphasize their embrace of equality and rejection of anything artificial. Communes sometimes practiced naturism, bringing unwanted attention from disapproving neighbors.[49]:197–199 In 1974, an article in The New York Times noted an increase in American tolerance for nudity, both at home and in public, approaching that of Europe.[50] By the 1990s, Americans had returned to their general disapproval of public nudity, although remaining liberal regarding sexual activity.[51]

Indigenous nudity[edit]

Indigenous cultures adapted to climates that do not require clothes as protection from the elements. All hunter-gatherer societies from prehistory to the present have one thing in common, being naked or nearly-naked (such wearing a loincloth![]() [52][53]) most of the time.[54]:3-4

[52][53]) most of the time.[54]:3-4

In urban areas of former colonies in Africa, South America and Oceania, contemporary behaviors combine traditions with Christian or Islamic religious teachings, with varying results. In rural areas, some societies continue to pursue a hunter-gatherer or pastoral way of life that includes functional nudity while doing work or bathing in natural bodies of water.[55]

Asian cultures[edit]

Outside of Western cultures societies retained some distinctiveness, not being dominated by Christian values.

In Southeast Asia, people initially had habits of dress and undress as in the warm climates, but were gradually changed by colonization and religious conversion.

In India, some Hindu[56] and Jain[57] ascetic monks![]() may have no possessions, including clothes. There were very few female ascetics who did the same, but one was Akka Mahadevi of Karnataka, a 12th century poet.[58]

may have no possessions, including clothes. There were very few female ascetics who did the same, but one was Akka Mahadevi of Karnataka, a 12th century poet.[58]

In remote tropical regions, some remaining indigenous peoples may retain pre-colonial minimal dress, both men and women covering only the lower part of the body, and removing all clothing to bathe in rivers or the ocean.

In temperate climates countries such as China adopted clothing that covered the body for comfort, and have values that relate modesty to maintaining "face![]() " and social order.[59]:378–380 In Japan, the tradition of mixed-gender communal bathing is maintained in some places, but is disappearing.[60] In Korea, public baths are gender-segregated, but nudity is required.[61]

" and social order.[59]:378–380 In Japan, the tradition of mixed-gender communal bathing is maintained in some places, but is disappearing.[60] In Korea, public baths are gender-segregated, but nudity is required.[61]

Islamic cultures[edit]

Islamic countries are guided by schools of law regarding public modesty that forbid nudity based upon the assumption that men are powerless to control their sexual urges. Since sinful thoughts will earn a believer an eternity in Jahannam, women are responsible for covering themselves, and may be punished severely or killed for disobeying the law. In Saudi Arabia and Qatar the niqab, the garment covering the whole female body and the face with a narrow opening for the eyes, is widespread. Hands are also hidden within sleeves as much as possible. The burqa, limited mainly to Afghanistan, also has a mesh screen which covers the eye opening.[62] In private, different rules apply to men, women, and children; and depend upon the gender and family relationship of others present.[63] Men need only cover themselves from navel to knees.[64]

Western culture[edit]

In mainstream Western cultures public, mixed-gender nudity, defined as not covering the genital areas, is generally prohibited; while gender-segregated nakedness may be expected in situations such as communal bathing or changing clothes. Social nudity may be permitted in private or semi-private situations.

Certain societies within the Western world, in which social and gender equality is greater, also allow for more mixed-gender situations where clothing is optional in public, in particular beaches and other recreational activities. Positive attitudes toward nudity are based upon long-standing traditions that provide early experiences of nudity as non-sexual, such as the use of the sauna in Northern Europe.[5] Social nudity has become normal in Germany to a greater extent than other countries, even within Europe.[65]

Private nudity[edit]

While behavior in private is influenced by social norms, there is more variation and individual differences. In societies where public nudity is rare, individuals tend to report that they are also not naked when home alone. However, behavior documented only by self-report is often unreliable. In a 2014 survey in the U.K., 42% responded that they felt comfortable naked and 50 percent responded they did not. Only 22% said they often walk around the house naked, 29% slept in the nude, and 27% had gone swimming nude.[66]

In societies that are often naked at home, not only alone but with family members, there is also more openness to clothing-optional behaviors in public.[7]:Ch.2

Nudity and moral emotions[edit]

The universality of bodily shame is not supported by anthropological studies, which do not find the use of clothing to cover the genital areas in all societies. Instead, people may be nude with no self-consciousness, and use adornments to call attention to sexuality.[67]:26 The shame regarding nudity is one of the exemplars of the emotion, but unlike positive examples of shame as motivation for improvement, body shaming is now generally thought of as psychologically harmful.[68][69]:11

Communal nudity[edit]

Between private and public spaces, there are activities where complete or partial nudity may be the norm. Places for these activities often limit access based upon age, gender, or other social characteristics, but generally include others who are not known, so behavior depends upon shared norms rather than prior relationships. Many of these spaces are facilities for athletics or hygiene; changing rooms, sports locker rooms and showers, steam rooms and saunas. However, communal nudity has served purely social functions as well.

Many cultures maintain a tradition of communal use of bathing facilities, such as the sauna, which is attended nude and usually mixed gender in Finland where it originated.[5] When Finns immigrated to the United States in the late 19th century, many settling in South Dakota, built saunas on their farms for family use that was social as well as hygienic. As saunas began to be built in towns, they became gender-segregated.[70]

The centuries-old Japanese tradition of communal use of public bathhouses[71] slowly declined as more homes had bathing facilities, and may be on the verge of extinction.[72]

Public nudity[edit]

The majority of Western societies define all public display of the genitals as disruptive or aggressive, and thus prohibit all public nudity as "indecent exposure". Some German cities have designated parks and beaches as clothing-optional, and those that do not want to see naked people can avoid those areas. Otherwise, societies may have no specific laws regarding public nudity, but apply laws against disorderly conduct to prohibit behavior that is disruptive. In the UK, authorities are advised to take no action regarding public nudity unless "members of the public were actually caused harassment, alarm or distress".[73] Stephen Gough, the "Naked Rambler" put this to the test by walking nude through the British countryside, and was jailed when he was nude where others objected.[74] Pursuing what he claimed as a legal right, Gough eventually lost his case before the European Court for Human Rights.[75]

Public partial or complete nudity is sometimes allowed at particular times and places, based upon allowing transgressive conduct during celebrations, following the traditions of Carnival as in Rio de Janero and New Orleans. Similar behaviors are seen at secular events, such as music and arts festivals.[76]

Topfreedom[edit]

Some women object to the prohibition of their being bare-chested in places where this is allowed for men.[77] In some jurisdictions, protests have been successful in establishing this right, but "topfreedom" may not be exercised due to resistance from the general public.[78] In 2020 the US Supreme Court refused to hear a case arguing that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment makes laws prohibiting topfreedom unconstitutional. However, the court citing the inclusion of female breasts, or specifically the nipple, in the legal definition of nudity in the US as precedent for retaining the restriction.[79] Islamic countries may react more severely, such as in Tunisia, putting a woman in a psychiatric hospital for posting a topless photo of herself on Facebook.[80]

Naturism[edit]

Naturism or nudism is the belief held by individuals that social nudity is beneficial in more situations than are recognized by mainstream cultures, defining naturists as the members of a subculture,![]() or as deviants.

or as deviants.![]() [81] Modern social nudism movements can trace their origin to Germany in the 1920s-1930s, where it emerged as a reaction to urbanization and rapid industrialization.[82][83] Nudist movements also argue that social nudism encourages body acceptance,[84] which is supported by British psychologist Keon West.[85][86][87] Furthermore, some will also argue that nudity eliminates the well-known[88] social stigmas, identities, paradigms, and sexualization associated with various forms of dress, creating a "more level playing field for human interactions".[89] A common assumption by non-nudists is that nudists are more sexually permissive, but this was not supported by research that found no difference between sexual attitudes and behaviors between nudists and non-nudists.[90]

[81] Modern social nudism movements can trace their origin to Germany in the 1920s-1930s, where it emerged as a reaction to urbanization and rapid industrialization.[82][83] Nudist movements also argue that social nudism encourages body acceptance,[84] which is supported by British psychologist Keon West.[85][86][87] Furthermore, some will also argue that nudity eliminates the well-known[88] social stigmas, identities, paradigms, and sexualization associated with various forms of dress, creating a "more level playing field for human interactions".[89] A common assumption by non-nudists is that nudists are more sexually permissive, but this was not supported by research that found no difference between sexual attitudes and behaviors between nudists and non-nudists.[90]

Naturism in Germany prior to World War II was viewed as serving the objectives of eugenics.[65][91]:117,178 At least one eugenics organization took out an advertisement in the leading British publication on naturism, Health and Efficiency (currently called H&E).[92] Pre-WWII naturism has been described as both utopian for its purported egalitarianism in Britain[93] and as fascist in Sweden,[94] but in both countries eugenics was an integral part of naturism.[93][94] Jonathan Margolis has argued that eugenics ideology has continued among British nudists but in the more attenuated form of lookism.[92]

Naturism in Germany[edit]

Prior to Michael Hau's publication of The Cult of Health and Beauty in Germany in 2003,[91] failed to examine naturism's racist and utopian aspects.[95]:11 Eugenics was integral to naturism prior to the end of World War II.[95]:145-147 Other aspects of Nazi Germany were also present among some naturism promoters, including antisemitism, racism, and German nationalism. Naturism was both condemned and promoted by different factions of Nazi Germany.[95]:49-58

Opposition to evidence-based medicine was also integral to this period, with promotion of homeopathy and vitalism, and opposition to vaccinations and germ theory.[95]:69-75 Beginning in the 1920s, naturists began to accept germ theory, but continued to advocate integrating nudity as a treatment into mainstream science,[95]:76-77 what would be called today "integrative medicine". The integration of sun and air treatments, and at times nudity, into German medicine continued into the Nazi era.[95]:78-81

Wilhelmine era (1890-1918)[edit]

The ideas of the nudism proponents of this era came out of the Völkisch (folkish) movement, which was a form of ethno-nationalism, with ideology that was "thoroughly reactionary, racist and anti-Semitiic".[96]:23 The two founders of modern naturism were Heinrich Pudor![]() (1865–1943) and Richard Ungewitter

(1865–1943) and Richard Ungewitter![]() (1869–1958), who both pioneered the Freikörperkultur

(1869–1958), who both pioneered the Freikörperkultur![]() (FKK) movement in Germany.[92] The Freikörperkultur movement was itself part of the German Lebensreform movement that started in the 1870s and also included the nascent alternative medicine, naturopathy, germ theory denial, the anti-vaccination movement, as well as reformist movements.[91]:1-2[97]

(FKK) movement in Germany.[92] The Freikörperkultur movement was itself part of the German Lebensreform movement that started in the 1870s and also included the nascent alternative medicine, naturopathy, germ theory denial, the anti-vaccination movement, as well as reformist movements.[91]:1-2[97]

Pudor published Nackende Menschen: Jauchzen der Zukunft in 1893[98] and Nackt-Kultur in 1906[99] (the title translates as "Naked Culture", but is often mistranslated as "The Cult of the Nude"). From 1912 onward, Pudor exclusively published his own antisemitic writings, starting with his Deutschland für die Deutschen! Vorarbeiten zu Gesetzen gegen die jüdische Ansiedlung in Deutschland ("Germany for the Germans! Preparatory work on laws against Jewish settlement in Germany") in 1912.[100]

Ungewitter established the FKK based on a number of pseudoscientific ideas about the purported health benefits of nudity, that wearing clothing could cause tuberculosis, and that the Sun's rays were generally beneficial to health, i.e., a panacea, because he believed the rays contained metals.[95]:69,89 While it's true that sunlight can treat some diseases,[101] it is not a panacea, and excessive sunlight can cause cancer. The idea that sunlight is a panacea is still current within the international naturist community, with the International Naturist Federation stating in 1994:[102]

“”The practice of communal nudity is an essential characteristic of naturism, making, as it does, the maximum use of the natural agents of sun, air and water. It restores one's physical and mental balance through being able to relax in natural surroundings, by exercise and respect for the basic principles of hygiene and diet.

|

Ungewitter was also an antivaxxer (and was contemptuous of evidence-based medicine[103]:53) and strongly antisemitic, even tying the two together, claiming that Jewish physicians were trying to destroy the German race by blood poisoning through vaccination.[91]:84-85,205-206 Ungewitter was also strongly antifeminist, believing that women should not compete economically with men and that their sole role in life was housewives. In 1953, Ungewitter was made an honorary member (Ehrenmitglied) of the German Association for Naturist Culture (Deutschen Verbandes für Freikörperkultur).[104][105]:6 Ungewitter wrote a statement of purpose that was explicitly eugenic in his book Nacktheit und Kultur (including text that translates as "prevention of 'degenerate offspring'", "Preservation of racial purity", and "Improvement of the Germanic race through a breeding policy favoring the blond and blue-eyed and including the Scandinavians."[91]:26-27[106]:122

Weimar Republic (1918-1933)[edit]

The Weimar era was characterized by a rise in factions with varying ideologies, with the two main camps being the far-right bourgeois camp accounting for about a quarter, and most of the remainder being socialist.[91]:24

The founder of organized socialist nudism was Adolf Koch![]() (1897–1970), who developed his ideas about nudism independently of the Völkisch movement. Koch developed a form of exercise call "Koch-Gymnastik" and opened a school called "Koch School".[91]:32-41 Koch had legal difficulties for his unorthodox views during the Weimar era, but his schools were apparently open to all, including Jews and atheists.[91]:31-33

(1897–1970), who developed his ideas about nudism independently of the Völkisch movement. Koch developed a form of exercise call "Koch-Gymnastik" and opened a school called "Koch School".[91]:32-41 Koch had legal difficulties for his unorthodox views during the Weimar era, but his schools were apparently open to all, including Jews and atheists.[91]:31-33

Hans Surén (1885–1972) was the most prominent popularizer of physical culture during Nazi Germany, and he produced many publications on both physical culture and nudism, with his most popular book being Mensch und die Sonne ("Man and the Sun"), first published in 1924, which promoted both gymnastics and nudism. The 1927 English translation of Mensch und die Sonne (Man and Sunlight) was a bestseller in the UK and was influential on the burgeoning UK nudist movement.[107][108]

Nazi Germany (1933-1945)[edit]

Despite being a raging antisemite in his later life, Pudor was imprisoned in 1933-1934 by the Nazis for criticizing the personality cult that surrounded Hitler, the Nazis being too tolerant of Jews, and the lifestyles of Hitler and Goebbels.

Although Koch's views during the Weimar era were unusually progressive within Weimar Republic and even the social democrats, in April 1933, at the beginning of Nazi Germany, Koch joined the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Nazi paramilitary organization for unknown reasons.[91]:52-54 On March, 1933, Hermann Göring had commanded the police in each state to destroy the FKK, which soon led to its dissolution.[91]:53-54 Koch's joining the SA prolonged the existence of his schools, but only until May 1934 when the SS murdered the SA leadership.[91]:55 After the dissolution of the SA, Koch joined the SS as a provisional member for 18 months.[91]:56 It is difficult to discern what Koch's motivations were for joining the Nazis, but the likeliest explanation is opportunistic, trying to save his schools. Koch even hid Jews from persecution by the Nazis, and according to his own account the denazification authorities in 1947 declared him as being active against fascism.[91]:56-57

Surén joined the Nazi Party in 1933[91]:189[109] Within the party, he became responsible for physical education, and was promoted to special plenipotentiary for rural physical education in 1936.[91]:59 According to Michael Hau, "Surén's career is an example of the straight path that led the völkisch wing of the German nude culture movement into the Third Reich."[91]:189 FKK and physical culture were both part of a larger Lebensreformbewegung (life reform movement) that began in the 19th century. The Nazi Party had viewed Surén's popularity as useful for their own ends and with Surén's assent, his views on life reform were merged into the Nazi racist concept of Aryanism.[91]:189-190,244 Also in 1936, Surén published a revised significantly expanded edition of Mensch und die Sonne to coincide with the 1936 Nazi Olympics that included quotes from Hitler's Mein Kampf, quotes from Joseph Goebbels and Alfred Rosenberg, and antisemitic passages.[110]:49-51,84[111] Surén eventually became a major in the SS.[91]:61,63 In 1942, Surén was expelled from the Nazi Party for public masturbation.[112]:161

In 1942, Himmler issued a directive that allowed nude bathing under certain conditions, a decree that remained in effect in postwar East and West Germany.[91]:63

Revisionism[edit]

Tireless naturism promoter Ed Lange![]() included a brief history about German naturism in his Family Naturism in Europe book. He showed awareness of Koch and the writings of Ungewitter, but did not acknowledge the eugenic aspects of early naturism and gave an incorrect view of naturism in Nazi Germany, implying that Hitler simply eliminated it in the early 1930s.[113]:16,18

included a brief history about German naturism in his Family Naturism in Europe book. He showed awareness of Koch and the writings of Ungewitter, but did not acknowledge the eugenic aspects of early naturism and gave an incorrect view of naturism in Nazi Germany, implying that Hitler simply eliminated it in the early 1930s.[113]:16,18

Gallery[edit]

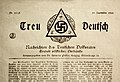

Pudor's periodical Treu Deutsch: Nachrichten des Deutschen Volksrates ("True German: News from the German People's Council") was an early example of the use of a swastika as a German ethno-nationalist symbol.

Súren's 1936 edition of Mensch und Sonne, page 54 is the last of 6 pages devoted to Goebbels[note 3]

Nudity in visual culture[edit]

Depictions of the body (dressed and undressed) define what each culture understands as normal, which is part of socialization. Pictorial conventions provide the contexts which make images comprehensible. In Western cultures, the basic contexts for images of nudity are information, art, and pornography. Images that do not fit into one of these categories may be misunderstood, leading to disputes. A perennial dispute is between art and porn, between those who see all nudity as sexual, and those who find artistic value in nude images, including some that are erotic.[114]

Visual arts[edit]

In most of the Western world, nudity has a symbolic meaning that is different from the everyday meaning of nakedness.[115] This difference was articulated by Kenneth Clark in The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form.[116] Clark defined "The Nude" as a work of art that used the body to symbolize beauty, strength, and emotion. Clark was writing in 1956, when the classical concepts in art that had begun in the Renaissance lingered in art history, but were being replaced in the art world by contemporary concepts. In the 1970s, John Berger said in Ways of Seeing![]() that the nude in Western art was voyeuristic and exploitative, while to be naked in real life was to be one's true self. The contemporary nude may be used to symbolize the reality of the human condition including gender, sexuality, violence, but also beauty redefined. However, the legacy of classical nudes remain in museums. In February 2018, in the wake of the MeToo movement,

that the nude in Western art was voyeuristic and exploitative, while to be naked in real life was to be one's true self. The contemporary nude may be used to symbolize the reality of the human condition including gender, sexuality, violence, but also beauty redefined. However, the legacy of classical nudes remain in museums. In February 2018, in the wake of the MeToo movement,![]() the Manchester Art Gallery

the Manchester Art Gallery![]() temporarily removed a painting of female nudes called Hylas and the Nymphs

temporarily removed a painting of female nudes called Hylas and the Nymphs![]() in order to "encourage debate" on how the female nude in art should be presented.[117]

in order to "encourage debate" on how the female nude in art should be presented.[117]

Historically, nudity was restricted by the Abrahamic religions in art as it was in life. Both orthodox Judaism and Islam forbids depictions of nudity, but in Christianity there is ambivalence. Few nudes were painted in the Middle Ages except Adam and Eve, but with the rediscovery of ancient statues, nudity became a frequent subject in Renaissance paintings of Biblical stories and classical mythology. In the Protestant Reformation, many of these works were destroyed, or genitals were covered by drapery or fig leaves. In America, fundamentalist Christians are once again seeking to restrict or eliminate the nude from art. In Mormon Utah in December 2017, an art teacher was fired for sharing postcards containing classic artwork for a fifth and sixth grade art lesson about color theory, postcards which happened to contain some nudes.[118][119]

Performing arts[edit]

Nudity has generally been accepted by Western societies in dance and theater presentations since the 1960s.[120]

Dance[edit]

Some contemporary choreographers consider nudity as one of the possible "costumes" available for dance, seeing nudity as expressing deeper human qualities through dance which works against the sexual objectification of the body in commercial culture.[121] Proponents of such nudity hold that there is a distinction between sexual and non-sexual or sensual nudity.[122]

Do ya think I'm sexy?[edit]

While some people, particularly naturists, may think that that nakedness by itself is never sexy. Others it would seem, particularly men, frequently disagree.[123][124]

In film, simulated nudity appeared as early as 1897 in Georges Méliès'![]() Après le Bal.[125] The first erotic film with nudity appeared in 1899 with Albert Kirchner's

Après le Bal.[125] The first erotic film with nudity appeared in 1899 with Albert Kirchner's![]() Le Coucher de la Mariée.[126] Is Your Daughter Safe? (1927) was the first exploitation film with nudity,[127] and nude photographer Albert Arthur Allen directed the forerunner of the "nudie-cutie" film with his 1927 Forbidden Daughters.[128] By 1934, the Hays Code

Le Coucher de la Mariée.[126] Is Your Daughter Safe? (1927) was the first exploitation film with nudity,[127] and nude photographer Albert Arthur Allen directed the forerunner of the "nudie-cutie" film with his 1927 Forbidden Daughters.[128] By 1934, the Hays Code![]() effectively eliminated nudity in films produced by Hollywood studios until 1968, but non-Hollywood films with nudity continued to be produced. Dziga Vertov's

effectively eliminated nudity in films produced by Hollywood studios until 1968, but non-Hollywood films with nudity continued to be produced. Dziga Vertov's![]() groundbreaking 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera featured the first film showing naturism (non-erotic).[129]

groundbreaking 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera featured the first film showing naturism (non-erotic).[129]

Nudist films were common in the 1930s (Elysia, Valley of the Nude in 1933,[130] This Nude World in 1935,[131] Nudist Land in 1937,[132] and The Unashamed in 1938[133]) The nudist camp genre was revived in the 1950s with changing censorship laws in the US, and Garden of Eden![]() was released in 1954. Prolific B-movie director Doris Wishman

was released in 1954. Prolific B-movie director Doris Wishman![]() began her career with several nudist films.[134] Russ Meyer

began her career with several nudist films.[134] Russ Meyer![]() had also kickstarted his exploitation film career with a nudist film in 1959, The Immoral Mr. Teas.[135]

had also kickstarted his exploitation film career with a nudist film in 1959, The Immoral Mr. Teas.[135]

But who formed the audience for these films? It seems unlikely unlikely that actual nudists would want to see a thinly-plotted films about nudists: why not just go to a naturist camp instead? More likely is that the films were pandering to the prurient interests of non-nudists. Indeed, such films have often been lumped into the "exploitation film" (or "sexploitation") category because of this.[136]:49

The rise and fall of nudist magazines paralleled that of nudist films. The Nudist (later renamed as Sunshine & Health) was published by the International Nudist Conference (INC), starting in 1938. The second issue of the magazine sold 50,000 copies, far exceeding the INC's membership, consequently it is believed that the magazine was primarily for sexual titilation of non-nudists.[137] Throughout the 1960s, Ed Lange, a nudist leader,[138] was a major publisher of nudist books and magazines in the US. He was also a supporter of the free love movement.[139] In at least one case Lange had collaborated with Meyer on a nudist book, The Wonderful Webbers: Naked & Together.[140] By then, Meyer was in the peak of his exploitation film career.

Pasco County, Florida, the "nudist capital of the world", has multiple nudist resorts, including both an old traditionalist family-friendly resort "Lake Como", and an upstart nudist adults-only sex club ("swinger") resort, "Caliente Club and Resort". The latter had been forced to change from a traditionalist club to a nudist sex club because of declining membership. Since the change, there has been conflict between Caliente and other traditionalist nudist clubs in the county, particularly Lake Como.[141]

Further reading[edit]

- Jablonski, Nina G. (2006). Skin: A Natural History. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520954816.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ The exception was for male citizens of Ancient Greece, for whom nudity in athletics and the symposium expressed their status of freedom, masculinity, privilege, and physical virtues.[23]:6,82

- ↑ In some Babylonian and Hebrew mythology, the first woman was Lilith, created from the same clay as Adam, but banished from Eden for being too independent. The Burney Relief is identified by some as Lilith.[33]

- ↑ Both editions of Súren's book were published in fraktur font. The font's poor readability made it that much harder to claim that one was only looking at the book for the text.

References[edit]

- ↑ "Carrer Argenteria, Barcelona". cityseeker. Retrieved 2023-10-14.

- ↑ Davies, Stephen (2020). Adornment: What Self-Decoration Tells Us about Who We Are. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-350-12100-3.

- ↑ Berner, Christoph; Schäfer, Manuel; Schott, Martin; Schulz, Sarah; Weingärtner, Martina (2019-06-27). Clothing and Nudity in the Hebrew Bible. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-67848-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten (2015). Veils, Nudity, and Tattoos: The New Feminine Aesthetic. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-0047-0.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sinkkonen, Jari (2013). "The Land of Sauna, Sisu, and Sibelius – An Attempt at a Psychological Portrait of Finland". International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies. 10 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1002/aps.1340.

- ↑ Möhring, Maren (2015). "Nudity is considered quite normal nowadays". Goethe Institute. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rough, Bonnie J. (2018-08-21). Beyond Birds and Bees: Bringing Home a New Message to Our Kids About Sex, Love, and Equality. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-58005-740-0.

- ↑ Wheeler, P.E. (1985). "The loss of functional body hair in man: the influence of thermal environment, body form and bipedality". Journal of Human Evolution. 14 (14): 23–28. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(85)80091-9.

- ↑ Daley, Jason (11 December 2018). "Why Did Humans Lose Their Fur?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Jablonski, Nina G. (1 November 2012). "The Naked Truth". Scientific American.

- ↑ Campbell, Bernard (2017-10-24). Human Evolution: An Introduction to Man's Adaptations (4 ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-78953-7.

- ↑ Jablonski, Nina G.; Chaplin, George (2000). "The Evolution of Human Skin Coloration". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (1): 57–106. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0403. PMID 10896812. S2CID 38445385.

- ↑ Jablonski, Nina G.; Chaplin, George (2017). "The Colours of Humanity: The Evolution of Pigmentation in the Human Lineage". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 372 (1724): 20160349. doi:10.1098/rstb.2016.0349. PMID 28533464.

- ↑ Jarrett, Paul; Scragg, Robert (2020). "Evolution, Prehistory and Vitamin D". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (2): 646. doi:10.3390/ijerph17020646. PMID 31963858.

- ↑ Sutou, Shizuyo (2012). "Hairless mutation: a driving force of humanization from a human-ape common ancestor by enforcing upright walking while holding a baby with both hands". Genes to Cells. 17 (4): 264–272. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2012.01592.x. PMID 22404045.

- ↑ Leary, Mark R; Buttermore, Nicole R. (2003). "The Evolution of the Human Self: Tracing the Natural History of Self-Awareness". Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 33 (4): 365–404. doi:10.1046/j.1468-5914.2003.00223.x.

- ↑ Nowell, April (2010). "Defining Behavioral Modernity in the Context of Neandertal and Anatomically Modern Human Populations". Annual Review of Anthropology. 39 (1): 437–452. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.105113. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ↑ Toups, M. A.; Kitchen, A.; Light, J. E.; Reed, D. L. (2010). "Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq234. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 20823373.

- ↑ Schlebusch; et al. (3 November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970. S2CID 206663925.

- ↑ Hollander, Anne (1978). Seeing Through Clothes. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-14-011084-4.

- ↑ Gilligan, Ian (2010). "The Prehistoric Development of Clothing: Archaeological Implications of a Thermal Model". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 17 (1): 15–80. doi:10.1007/s10816-009-9076-x. S2CID 143004288.

- ↑ Batten, Alicia J. (2010). "Clothing and Adornment". Biblical Theology Bulletin. 40 (3): 148–59. doi:10.1177/0146107910375547. S2CID 171056202.

- ↑ Kyle, Donald G. (2014). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Ancient Cultures; v.4 (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-118-61380-1.

- ↑ Simmons, Pauline; Yarwood, Doreen; Laver, James; Murray, Anne Wood; Marly, Diana Julia Alexandra (April 6, 2022). Dress – the Nature and Purposes of Dress. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - ↑ 25.0 25.1 Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Sweeney, Deborah (2006). "On Nakedness, Nudity, and Gender in Egyptian and Mesopotamian Art". In Schroer, Sylvia (ed.). Images and Gender: Contributions to the Hermeneutics of Reading Ancient Art. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen: Academic Press Fribourg.

- ↑ Mark, Joshua J. (27 March 2017). "Fashion and Dress in Ancient Egypt". World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Mouratidis, John (1985). "The Origin of Nudity in Greek Athletics". Journal of Sport History. 12 (3): 213–232. ISSN 0094-1700. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- ↑ Ariès, Philippe; Duby, Georges, eds. (1987). From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. A History of Private Life. Vol. I. Series Editor Paul Veyne. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39975-7.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Brundage, James A. (2009-02-15). Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-07789-5.

- ↑ Fagan, Garrett G. (2002). Bathing in Public in the Roman World. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472088653.

- ↑ Dendle, Peter (2004). "How Naked Is Juliana?". Philological Quarterly. 83 (4): 355–370. ISSN 0031-7977. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ↑ Barcan, Ruth (2004). Nudity: A Cultural Anatomy. Berg Publishers. ISBN 1859738729.

- ↑ "Lilith | Definition & Mythology". 2023-10-03. Retrieved 2023-10-08.

{{cite web}}: Text "Britannica" ignored (help) - ↑ Velleman, J. (2001). "The Genesis of Shame". Philosophy and Public Affairs. 30 (1): 27–52. doi:10.1111/j.1088-4963.2001.00027.x. hdl:2027.42/72979. S2CID 23761301.

- ↑ "The Woman Deacon's role at Baptism". Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ Lerner, Robert E. (1972). The Heresy of the Free Spirit in the Later Middle Ages. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- ↑ Livingstone, E. A., ed. (2013). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199659623.

- ↑ Szreter, Simon; Fisher, Kate (2010). Sex Before the Sexual Revolution: Intimate Life in England 1918–1963. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139492898.

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald (2017). The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present. Yale University Press.

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald (2000). Triumph of the Moon. Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-500-27242-5.

- ↑ Mostly SFW

- ↑ "Llewellyn Encyclopedia and Glossary: Skyclad".

- ↑ Basden, George T. (1921). Among the Ibos of Nigeria. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

- ↑ Kohn, Margaret; Reddy, Kavita (2023). "Colonialism". In Edward N. Zalta; Uri Nodelman (eds.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Masquelier, Adeline Marie (2005). "An Introduction". In Masquelier, Adeline Marie (ed.). Dirt, Undress, and Difference Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 1–33. ISBN 0253111536.

- ↑ Stevens, Scott Manning (2003). "New World Contacts and the Trope of the 'Naked Savage". In Elizabeth D. Harvey (ed.). Sensible Flesh: On Touch in Early Modern Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 124–140. ISBN 9780812293630.

- ↑ Vinken, Henk; Soeters, Joseph; Ester, Peter, eds. (2004). "Cultures and Dimensions". Comparing Cultures: Dimensions of Culture in a Comparative Perspective. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklyjke Brill, NV. ISBN 90-04-13115-9.

- ↑ Global Gender Gap Report 2020 (PDF) (Report). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ↑ Miller, Timothy (1999). The 60s communes: hippies and beyond. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2811-8.

- ↑ Sterba, James (3 September 1974). "Nudity Increases in America". The New York Times.

- ↑ Layng, Anthony (1998). "Confronting the Public Nudity Taboo". USA Today Magazine. Vol. 126, no. 2634. p. 24.

- ↑ loincloth Languages of hunter-gatherers and their neighbors, University of Texas.

- ↑ Loincloth pongo Ethan Rider.

- ↑ Gilligan, Ian (2018-12-13). Climate, Clothing, and Agriculture in Prehistory: Linking Evidence, Causes, and Effects. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108555883. ISBN 978-1-108-47008-7. S2CID 238146999.

- ↑ Nowell, April (2010). "Defining Behavioral Modernity in the Context of Neandertal and Anatomically Modern Human Populations". Annual Review of Anthropology. 39 (1): 437–452. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.105113. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ↑ Hartsuiker, Dolf (2014). Sadhus: Holy Men of India. Inner Traditions. p. 176. ISBN 978-1620554029.

- ↑ Dundas, Paul (2004). The Jains. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203398272. ISBN 9780203398272.

- ↑ "The Naked Saint". Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ↑ Hansen, Karen Tranberg (2004). "The World in Dress: Anthropological Perspectives on Clothing, Fashion, and Culture". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33: 369–392. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143805. ISSN 0084-6570. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- ↑ Hadfield, James (10 December 2016). "Last splash: Immodest Japanese tradition of mixed bathing may be on the verge of extinction". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ↑ Milner, Rebecca (23 August 2019). "First-time jjimjilbang: how to visit a Korean bathhouse". Lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ↑ Al-Absi, Marwan (2018). "The Concept of Nudity and Modesty in Arab-Islamic Culture" (PDF). European Journal of Science and Theology: 10.

- ↑ Mughniyya, Muhammad Jawad (n.d.). "The Rules of Modesty". Al-Islam.org. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ↑ al-Qaradawi, Yusuf (2013-10-11). The Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam: الحلال والحرام في الإسلام. ISBN 978-967-0526-00-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|ppublisher=ignored (help) - ↑ 65.0 65.1 Nudity is considered quite normal nowadays Petra Märlender interview of Maren Möhring (February 2015) Goethe-Institut (archived from February 15, 2018).

- ↑ "YouGov Survey Results" (PDF). YouGov.com. 2014-10-29. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ↑ Cordwell, Justine M.; Schwarz, Ronald A., eds. (1979). The Fabrics of Culture: The Anthropology of Clothing and Adornment. Chicago, IL: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-163152-3.

- ↑ Deonna, Julien A.; Rodogno, Raffaele; Teroni, Fabrice (2012). In Defense of Shame: The Faces of an Emotion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199793532.

- ↑ Thomason, Krista K. (2018). Naked: The Dark Side of Shame and Moral Life. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190843274.003.0007.

- ↑ Sando, Linnea C. (2014). "The Enduring Finnish Sauna in Hamlin County, South Dakota". Material Culture. 46 (2): 1–20. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ Kawano, Satsuki (2005). "Japanese Bodies and Western Ways of Seeing in the Late Nineteenth Century". In Masquelier, Adeline (ed.). Dirt, Undress, and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21783-7.

- ↑ Hadfield, James (10 December 2016). "Last splash: Immodest Japanese tradition of mixed bathing may be on the verge of extinction". The Japan Times. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ↑ "Nudity in Public - Guidance on handling cases of Naturism". The Crown Prosecution Service. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

Nudity in public alone with no aggravating features is very unlikely to amount to ... offence.

- ↑ "Nudity in Public - Guidance on handling cases of Naturism". The Crown Prosecution Service. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

Nudity in public alone with no aggravating features is very unlikely to amount to ... offence.

- ↑ Shaw, Danny (28 October 2014). "Naked rambler Stephen Gough loses human rights case". BBC News. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ Bennett, Theodore (2020-06-11). "State of Undress: Law, Carnival and Mass Public Nudity Events". Griffith Law Review. 29 (2): 199–219. doi:10.1080/10383441.2020.1774971. ISSN 1038-3441.

- ↑ Williams, Pete (19 August 2019). "Women ask Supreme Court to toss topless ban: Why are rules different for men?". NBC News.

- ↑ Jensen, Robin (2004). "Topfreedom: A rhetorical analysis of the debate with a bust". Women and Language. 27 (1). Urbana: 68–69.

- ↑ Hurley, Lawrence (2020-01-13). "U.S. Supreme Court refuses to 'Free the Nipple' in topless women case". Reuters. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ↑ Tayler, Jeffrey (22 March 2013). "Tunisian Woman Sent to a Psychiatric Hospital for Posting Topless Photos on Facebook". The Atlantic.

- ↑ *"Nudism". Grinnell University: Subcultures and Sociology. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ↑ "The Waxing and Waning of Nudism in America", The Star, November 17 2015

- ↑ "Turning to Nature in Germany: Hiking, Nudism, and Conservation, 1900-1940", John Alexander Williams, Stanford University Press, 2007

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions About Nude Recreation, AANR

- ↑ West, Keon (2018-03-01). "Naked and Unashamed: Investigations and Applications of the Effects of Naturist Activities on Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction". Journal of Happiness Studies. 19 (3): 677–697. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9846-1. ISSN 1573-7780. S2CID 9153791.

- ↑ West, Keon (2020a). "A Nudity-Based Intervention to Improve Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction". International Journal of Happiness and Development. 6 (2): 162–172. doi:10.1504/IJHD.2020.111202. ISSN 2049-2790. S2CID 243517121. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ↑ West, Keon (2020b). "I Feel Better Naked: Communal Naked Activity Increases Body Appreciation by Reducing Social Physique Anxiety". The Journal of Sex Research. 58 (8): 958–966. doi:10.1080/00224499.2020.1764470. ISSN 0022-4499. PMID 32500740. S2CID 219331212. Retrieved 2021-02-23.

- ↑ "Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in Clothing", Diana Crane, University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- ↑ Hile, Jennifer (2004). "The Skinny on Nudism in the U.S." National Geographic. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ↑ Story, Marilyn D. (1987). "A Comparison of Social Nudists and Non-Nudists on Experience with Various Sexual Outlets". The Journal of Sex Research. 23 (2): 197–211. doi:10.1080/00224498709551357. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ 91.00 91.01 91.02 91.03 91.04 91.05 91.06 91.07 91.08 91.09 91.10 91.11 91.12 91.13 91.14 91.15 91.16 91.17 91.18 The Cult of Health and Beauty in Germany: A Social History, 1890-1930 by Michael Hau (2003) University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226319768.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 Dark side of fresh air Utopians: Jonathan Margolis explores the strange history and surprising new owners of H&E magazine, now 100 by Jonathan Margolis (11 Jun 1999 22.45 EDT) The Guardian.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Utopian Bodies and Anti-fashion Futures: The Dress Theories and Practices of English Interwar Nudists by Annebella Pollen (2017) Utopian Studies 28(3):451-481.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "The Paradoxes of Paradisiac Nudity: Fascist Aesthetics And Medicalised Discourse in the 1930's Nudist Movement, Health Through Nude Culture" by Ylva Habel (2000) The Nordic Journal of Aesthetics 12(22):13-27. doi:10.7146/nja.v12i22.3132.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 95.3 95.4 95.5 95.6 Naked Germany: Health, Race and the Nation by Chad Ross (2005) Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 1859738613.

- ↑ Turning to Nature in Germany: Hiking, Nudism, and Conservation, 1900-1940 by John Alexander Williams (2007) Stanford University Press. ISBN 080470015X.

- ↑ See the German Wikipedia article on Lebensreform.

- ↑ Nackende Menschen: Jauchzen der Zukunst by Heinrich Pudor (1893) Scham.

- ↑ Nackt-Kultur by Heinrich Pudor (1906) Steglitz. Two volumes.

- ↑ Deutschland für die Deutschen! Vorarbeiten zu Gesetzen gegen die jüdische Ansiedlung in Deutschland by Heinrich Pudor (1912) Hans Sachs-Verlag. Two volumes.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Light therapy.

- ↑ INF Nude Travel Guide: Naturism/1994/95 Elysium Growth Press. ISBN 1555990495.

- ↑ Nationalism and Sexuality: Middle-Class Morality and Sexual Norms in Modern Europe by George L. Mosse (1985) Howard Fertig. ISBN 0865273502.

- ↑ Archiv - Katalog 8 - Lebensreform, Völkische Bewegung u. Ariosophie Versandantiquariat Hans-Jürgen Lange.

- ↑ "FreiKörperKultur in Berlin: 50. Todestag von Adolf Koch" by Jürgen Krüll (December 2020) FreiKörperKultur. Page 3-6.

- ↑ Nacktheit und Kultur: Neue Forderungen by Richard Ungewitter (1913) Rich. Ungewitter.

- ↑ Man and Sunlight by Hans Surén, translated by David Arthur Jones (1927) Sollux.

- ↑ "Naked in Nature: Naturism, Nature and the Senses in early 20th Century Britain" by Nina J. Morris (2009) Cultural Geographies 6(3):283-308. doi:10.1177/1474474009105049.

- ↑ Mensch und die Sonne by Hans Surén (1924) Dieck.

- ↑ Mensch und Sonne: Arisch-olympischer Geist by Hans Surén (1936) Scherl.

- ↑ See the German Wikipedia article on Hans Surén

- ↑ Die deutsche Seele by Thea Dorn & Richard Wagner (2011) Knaus. ISBN 3813504514.

- ↑ Family Naturism in Europe by Ed Lange (1982) Elysium Growth Press. ISBN 0910550204.

- ↑ Eck, Beth A. (December 2001). "Nudity and Framing: Classifying Art, Pornography, Information, and Ambiguity". Sociological Forum. 16 (4): 603–632. doi:10.1023/A:1012862311849. S2CID 143370129.

- ↑ Bonfante, Larissa (1989). "Nudity as a Costume in Classical Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 93 (4): 543–570. doi:10.2307/505328. ISSN 0002-9114. S2CID 192983153. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ↑ Clark, Kenneth (1956). The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01788-3 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "Presenting the female body: Challenging a Victorian fantasy", Manchester Art Gallery blog post, archived on 2018 February 1

- ↑ "Utah art teacher fired over classical nude images wants an apology from school district" by Kelly Schmidt, Salt Lake Tribune, 2018 January 3

- ↑ "Utah Art Teacher Fired for Unintentionally Sharing Classical Nude Paintings Speaks Out" by Cathy Free, People, 2018 January 4

- ↑ Toepfer, Karl (2003). "One Hundred Years of Nakedness in German Performance". The Drama Review. 47 (4). MIT Press: 144–188. doi:10.1162/105420403322764089. ISSN 1054-2043. S2CID 57567622.

- ↑ Cappelle, Laura; Whittenburg, Zachary (1 April 2014). "Baring It All". Dance Magazine.

- ↑ "Sensual Vs. Sexual, The difference between sensuality and sexuality".

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Male gaze.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Female gaze.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on After the Ball.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Le Coucher de la Mariée.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Is Your Daughter Safe?.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Forbidden Daughters.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Man with a Movie Camera.

- ↑ Elysia (Valley of the Nude) IMDb

- ↑ This Nude World. Back To Nature Internet Archive.

- ↑ Nudist Land IMDb.

- ↑ The Unashamed IMDb.

- ↑ Doris Wishman (1912-2002) IMDb.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on The Immoral Mr. Teas.

- ↑ "Women's Cinema as Counterphobic Cinema: Doris Wishman as the Last Auteur" by Tania Modleski. In: Sleaze Artists: Cinema at the Margins of Taste, Style, and Politics, edited by Jeffrey Sconce (2007) Duke University Press. ISBN 0822339641.

- ↑ "'A Certain Amount of Prudishness': Nudist Magazines and the Liberalisation of American Obscenity Law, 1947–58" by Brian Hoffman (22 October 2010) Gender & History 22(3):708-732. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2010.01611.x.

- ↑ Ed Lange: Leading Advocate of Nudism by Myrna Oliver (May 10, 1995 12 AM PT) Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Going back to Paradise, Elysium Fields: Topanga’s Clothing-Optional Club by R. W. Klarin (March 11, 2017) Living the Dream Deferred.

- ↑ The Wonderful Webbers: Naked & Together by Ed Lange et al. (1967) Elysium. ISBN 0910550190.

- ↑ Purists v partiers: the battle between two popular nudist resorts: One of Florida’s oldest and most staid communities, Lake Como, and nearby Caliente Club struggle with being misunderstood – and with each other by Jordan Blumetti (25 Nov 2019 08.08 EST) The Guardian.