Founding Fathers

| God, guns, and freedom U.S. Politics |

| Starting arguments over Thanksgiving dinner |

| Persons of interest |

| —Samuel Johnson in Taxation, No Tyranny, discussing the Founding Fathers' attachment to slavery.[1] |

“”I think it's important to remember that these men are not perfect. If they were marble gods, what they did wouldn't be so admirable. The more we see the founders as humans the more we can understand them.

|

| —David McCullogh[2] |

The Founding Fathers are a loosely defined group of (mostly young)[3] men who were instrumental to the establishment of what we now know as the United States of America. Ohio senator (and future president) Warren G. Harding coined the term during his keynote speech at the 1916 Republican National Convention.[4] In general, those referred to as the Founding Fathers include military leaders of the American Revolutionary War, the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and those who worked on drafting the U.S. Constitution and its Bill of Rights eleven years later.

America takes its Founding Fathers very seriously, and in many ways to an extreme level. Often to the point where one would say "the Founding Fathers would be ashamed of you" for whatever your politics may be, while rarely actually researching their beliefs and opinions and adapting one's own to match theirs. To play that game is an absurdity, since the Founding Fathers most definitely did not agree with each other on all topics, and they don't even have opinions on most modern political matters due to having been dead for centuries.[5]

Assuming they would agree with one's already established beliefs is so much easier — eerily similar to the question, "What would Jesus do?"[note 1] Unfortunately, the left and right are equally guilty of this. The mythologization of the Founding Fathers forms an important aspect to American exceptionalism. In reality, it shouldn't need to be said that the Founders were all very flawed human beings who disagreed with each other on any number of issues.

Who is a Founding Father?[edit]

There are over 130 people who can be considered to be among the Founding Fathers of the United States, and nobody has heard of most of them (but God help you if you run into one of their spawn at a party in the Hamptons).[6] According to the guy everyone agrees is the best historian on the subject, the seven most important founding fathers were Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton.[7] So nobody else mattered.

These seven people were particularly instrumental in the shape the country was to take, but many of the 126 other official Founding Fathers did and said a lot of important things as well.

And who says it's all about the A-List? There were thousands of people across the country who are not officially considered Founding Fathers, yet who had great influence. James Iredell is not an official Founding Father, but he's hardly just some Carolina cracker. Iredell sat on the very first Supreme Court and wrote the lone dissent in Chisholm v. Georgia, disagreeing with Founding Father A-Listers John Jay, James Wilson, and John Blair. Everyone was so mad at the A-Listers that the country just two years later ratified the Eleventh Amendment overturning their ruling. Iredell helped organize the court system of North Carolina, and some manifesto he wrote predated the Declaration of Independence, but said a lot of the same stuff and his dissent became the Eleventh Amendment, more or less. Yet he's B-List, if even.

Citing the founding fathers is tricky with even the A-List founders and their wildly divergent opinions, to say nothing if you start to include B-Listers like Iredell.

Most notable[edit]

George Washington, the Hero[edit]

Washington is easily the most famous and mythologized of the American Founders. In his political time, he ended up being perhaps the most important. He wasn't too active in the early stages of the American Revolution, but he served as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army and thus played a vital role in defending the revolution.[8]

After the war, Washington resigned his commission, but he had become a national hero. After the failures of the Articles of Confederation, Washington emerged from his Virginia plantation to play a role in the Constitutional Convention. He mostly just sat there quietly, but his personal prestige greatly aided in the legitimacy of the proceeding.[9] Washington's endorsement of the final product helped ensure that the Constitution would be ratified.

He then served as the first US president, having been all-but forced into the role despite having no desire to do such.[10] He did much to shape the office, and his leadership style once again consisted of sitting quietly and letting his subordinates debate among themselves before making a decision based on what he'd heard.[11] He generally favored Hamilton's policies, leading to resentment from Thomas Jefferson. However, Washington's hero status ensured that political differences remained suppressed and that the country held together under his leadership.[12] He finally stepped down after suffering from a long string of illnesses, having served only two terms.

Washington owned slaves at his plantation and allowed the use of physical punishments against them.[13] He also published a fugitive slave advertisement while he was in office as president.[14] Washington did write in his will that his slaves were to be emancipated when his wife died,[15] despite that he is quoted as having said "There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of slavery."[16]

John Adams, the Lawyer[edit]

John Adams was a Boston lawyer who fought for the right to be presumed innocent when accused of crimes. He most notably put that principle into play when defending the hated perpetrators of the Boston "Massacre" and winning acquittal for them.[17] He then served in the Continental Congress, where he pushed for ensuring the right to trial by fair jury and where he became one of the most committed proponents of independence.[18] Adams also took part in the committee that helped draft the Declaration of Independence.[19]

Adams had deep political differences with his rival Thomas Jefferson, and the election of 1796 was one of the most bitter in American history.[20] As president, Adams struggled against hostility from Jefferson's faction and his personal differences with Alexander Hamilton and his loyalist faction within Adams' own party.[21] To make matters worse, he also signed the deeply authoritarian and unpopular Alien and Sedition Acts, which made him lose his bid for reelection in 1800.[22] On the plus side, though, he Adams was instrumental in preventing a war with France, keeping America out of war with Europe, created the Department of Navy, appointed William Henry Harrison as governor of the new Indiana Territory, signed a law to protect shipping rights and also signed a law mandating publicly-funded hospitals for US navy sailors and veterans.[23] He also opposed slavery.

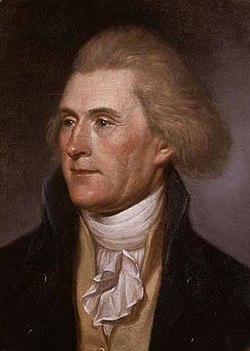

Thomas Jefferson, the Militant[edit]

“”And what country can preserve its liberties if their rulers are not warned from time to time that their people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms... The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.

|

| —Jefferson in 1787.[24] |

Jefferson was one of the more strident voices for independence. In 1774, he wrote the pamphlet "A Summary View of the Rights of British America", in which he argued that the American colonies had the just right to rule themselves and that British laws were illegitimate.[25] In Congress, he was one of the youngest delegates, but his writing skills ensured that he was the primary pen behind the Declaration of Independence. Well, that and the fact that Adams didn't want to do it.[26]

In his home state of Virginia, Jefferson pushed for radical policies like eliminating certain inheritance rights,[27] establishing public-funded schools for all citizens,[28] and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom/Jefferson's Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom.[29] Jefferson then served as the US Ambassador to France, where he directly took part in the French Revolution.[30][31] He remained an ardent supporter of the French even after heads started rolling and many of his own countrymen became distressed.

Jefferson's presidency was marked by great leaps forward in westward expansion, but this was sadly coupled with Indian removal policies.[32] Within the US, he pushed for increases in voter franchise to ensure that unlanded white men would be able to participate in democracy as well.[33] He also fought pirates in the Mediterranean and ramped up hostilities with the British.

As a wealthy Virginian, Jefferson was also a controversial slave-owner who fathered six children with his slave Sally Hemmings. Despite this, he was personally not a fan of slavery, although he also took the view that the federal government forcefully emancipating slaves would not be a good idea.[34]

James Madison, the Writer[edit]

James Madison's primary role in the revolution was pushing for reform of the Articles of Confederation and finally being the primary voice calling for the Constitutional Convention.[35] He was also the primary force pushing for the Bill of Rights amendments to be tacked onto it. Although he joined with Alexander Hamilton to write the Federalist Papers in support of the Constitution's ratification, he later turned on Hamilton after disagreeing with his centralization policies and helped found a political party to oppose him.

As president, Madison led the country into the War of 1812. The war was incompetently handled against the British, but the primary goal of destroying Native American threats was realized. The war helped convince Madison of the need for a more centralized federal government. Madison was also a Virginia slave-owner.

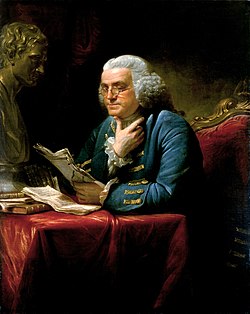

Benjamin Franklin, the Genius[edit]

One of the oldest Founding Fathers (more like Founding Grandpa), Benjamin Franklin was a widely-recognized genius and inventor whose lightning rod and bifocal discoveries are still in use to this day.[36] He gained political prominence as the publisher of a revolutionary newspaper, the Pennsylvania Chronicle.[37]

In the revolution, Franklin joined the committee to help write the Declaration of Independence. He then became America's chief diplomat in France, where he helped secure the French alliance during the war and negotiate the end of that war in 1783. His personal prestige also helped lend legitimacy to the Constitutional Convention.

Alexander Hamilton, the Authoritarian[edit]

Alexander Hamilton was born as a bastard orphan in the British Leeward Islands![]() before gaining prominence as a senior aide to General George Washington during the Revolutionary War. He was a leader in calling for a Constitutional Convention to replace the Articles of Confederation, and he wrote 51 of the 85 chapters of the Federalist Papers to support the ratification of the new Constitution. As Treasury Secretary under George Washington, Hamilton successfully pushed for legal authority to fund the national debt, to assume states' debts, and to create the government-backed Bank of the United States.

before gaining prominence as a senior aide to General George Washington during the Revolutionary War. He was a leader in calling for a Constitutional Convention to replace the Articles of Confederation, and he wrote 51 of the 85 chapters of the Federalist Papers to support the ratification of the new Constitution. As Treasury Secretary under George Washington, Hamilton successfully pushed for legal authority to fund the national debt, to assume states' debts, and to create the government-backed Bank of the United States.

However, Hamilton was also an elitist who reviled the concept of popular democracy and wanted to restore an elected monarchy to the United States.[38] Hamilton also advocated for a military crackdown on the Whiskey Rebellion and endorsed the Alien and Sedition Acts. He hated the French Revolution and pushed for war against France, even hoping to use his military position to crack down on dissent in Virginia and then attack Spain's colonies bordering America.[39] He also had a longtime rivalry with Aaron Burr which led to a duel that Hamilton ended up murdered by Burr.

John Jay, the Diplomat[edit]

John Jay was a wealthy New York lawyer who helped organize the state's resistance to the British. He briefly served as the President of the Continental Congress, but they soon sent him off to be a diplomat in Spain and then France, where he helped negotiate a favorable peace agreement with the British in 1783.[40] On his return from abroad, Jay found that Congress had placed him in charge of the new nation's foreign affairs, but his powers were so limited by the Articles of Confederation that the job was pointless. Jay was infuriated by this, and he became one of the chief proponents calling for a Constitutional Convention. He later joined Hamilton in writing the Federalist Papers. Under the new Constitution, Jay became the first Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, where he helped affirm that states were and are legally subordinate to the federal government.[40] While serving as Chief Justice, Jay did the even more important job of negotiating a treaty with the British which resolved many outstanding issues after the war.[41] He then stepped down from the court and served as governor of New York.

On the issue of slavery, Jay became a soft abolitionist despite the fact that his father was a wealthy plantation-owner.[42] Jay advocated for purchasing and freeing slaves, which he did himself, and he used his position to push for policies calling for the gradual phasing-out of slavery. His policies while governor of New York were a major factor ensuring that New York became a free state.[42] He instilled his abolitionist values into his son, William Jay, who became an even more determined abolitionist who later helped found the Republican Party.[42]

Other Founding Fathers[edit]

- Thomas Paine - Stirred the country to war, then wrote the best defense of freedom of religion ever. His pamphlets at some times outsold Shakespeare.

- John Marshall - Pretty much created the American judiciary system as we know it.

- Patrick Henry - Known for being the "voice of the revolution," he is also the fundamentalist's favorite founder.

- Aaron Burr - Mostly known for killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel (which effectively killed both dueling and his political career); also tried to get the Western part of the country to secede.

- John Hancock

- Most Americans know him for his large signature on the Declaration of Independence.[43] President of the Second Continental Congress.

- Most Americans know him for his large signature on the Declaration of Independence.[43] President of the Second Continental Congress. - George Mason

- He wrote both the Fairfax Resolves and the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

- He wrote both the Fairfax Resolves and the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

Mommies[edit]

Believe it or not, there were several important founding mothers. Important ladies include:

- Martha Washington - First First Lady.

- Abigail Adams - Kept John Adams grounded. - Is often cited as one of the most important female figures of her time. The fact that the extensive correspondence between her and her husband survives may have aided in that. Said letters deal with politics and related subjects, as well as other things.

- Betsy Ross - Designed the American flag, at least according to legend; evidence for this is noticeably absent.[44]

- "Molly Pitcher" - The wife of an officer who took over her husband's post after he was wounded.

- Dolly Madison - Main rival of Hostess Twinkies, until Hostess Brands bought them out in the 1990s. Dolley Madison, on the other hand, saved much of the White House's art during the War of 1812 (damn Canadians).

[edit]

“”Surely the people who wrote and signed the Constitution of the United States of America can be trusted to tell us what it means. Original letters written in their own words give us a much truer understanding of their intentions than third party commentaries written a hundred years later.

|

| —ChristianParents.com[45] |

The quote above is true if you assume that these 130 people all believed the same things; that the Founding Fathers were an intellectual monolithic entity that knew exactly the effect of all their words; that no debate nor compromise was involved in the writing of the Constitution; and that wording was not purposefully vague because they could not agree on their meanings at the framing.

This line of reasoning should lead you to question why the founding fathers even felt the need for a Supreme Court (and the ability to add and repeal amendments to the Constitution), since everyone knew what the document said and meant. Simply cracking the Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers should dispel this notion rather quickly.[46] And just a couple of examples of the divisions between the founders: The Bill of Rights itself (tacked on to please the Anti-Federalists) and the Three-Fifths Compromise. There are also the rather unsavory facts about how the founders immediately began to violate the Constitution after they had been elected into office, e.g. John Adams' signing the Alien and Sedition Acts and Thomas Jefferson's purchase of the Louisiana territory from the French.

In reality, it was just pure luck that they could stop bickering for long enough to keep the country together. The country was rallied around two sides: the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists. After the somewhat authoritarian presidency of John Adams, followed by 28 years of Jeffersonian Republicans, which caused an effective one-party state from 1812 to 1824. It was sheer luck that the country never fell apart. If it weren't for the threat of Britain and the natives which we intended to steal all the land from, they probably would've failed. So in reality, the US government back then was enough to make the modern US look like a monolithic voting bloc. In addition to this, some states had real diplomatic tensions. For example, Virginia and Ohio would've probably gotten really mad over the Ohio River.

So you've dug up some Founding Father who wrote something that backs up what you think, and this is great. Because now whatever belief you hold is shared by the monolithic Founding Fathers and you can pull out your quote to prove you are right. For example, here's a tidbit from lexicographer Noah Webster that would surprise some people:

“”An equality of property... constantly operating to destroy combinations of powerful families, is the very soul of a republic... Let the people have property, and they will have power — a power that will for ever be exerted to prevent a restriction of the press, and abolition of trial by jury, or the abridgement of any other privilege.

|

| —Noah Webster (yes, the dictionary guy), "proposing" socialism before Marx was even born.[47] |

Here's how to overcome some pitfalls. In the unlikely event that somebody in earshot has read a book and says "How can you say that? These men were immediately arguing in the Supreme Court about what they meant in the Constitution!" you should say that was all just pencil sharpening, and tell them to stop with the evil liberal claptrap.

If you cite the Founding Fathers' "original intent," it's possible that someone will point out that there were Founding Fathers who thought and wrote the exact opposite things that you're claiming. History calls some of this nonsense "Federalist v. Anti-Federalist"; "Big State v. Little State"; and "Federalism v. Republicanism." To win, just say that particular Founding Father was an idiot everyone actually hated.[48] Say that "the Founding Fathers believed X and Founding Father Y wrote this in a letter" and the implication is that they all believed as Founding Father Y, whose ideas were cheered and adopted by everyone! Argument won, because you get to say, whoever you are arguing with over whatever position, that it is originalist.

Proponents of the legal doctrine of originalism often make references to these 130 men and what they thought about stem cell research, automatic weapons, segregation,[49] and the humor of George Carlin.[50] Interestingly, the family values of Ben C-Note Benjamin Franklin are rarely if ever cited.

Deists, Christian soldiers, or Satanic atheists?[edit]

While fundamentalist Christians like to claim that all these men were devout Christians, in truth, most were deists (in the classical sense where an individual's relationship with God is impersonal), though their individual religious stances were as varied as night and day. Above all, however, they held secularist viewpoints, strongly influenced by the Enlightenment, and had strong opinions in favor of insulating religious matters from state interference — and vice versa.

Benjamin Franklin edited out Thomas Jefferson's initial line in the Declaration of Independence: "We hold these truths to be sacred..." and changed it to: "We hold these truths to be self-evident..." So much the worse for the theory of a Christian source for the founding document.[51] Instead of elevating rights as sacred revealed truths, the patres patriae![]() held up rights as purely intellectual axioms. Thomas Jefferson said that the Declaration of Independence was "an expression of the American mind". Now, if he had said it was "an expression of the American faith", like the Religious Right currently claims (and retrojects into the document), they might have a point.

held up rights as purely intellectual axioms. Thomas Jefferson said that the Declaration of Independence was "an expression of the American mind". Now, if he had said it was "an expression of the American faith", like the Religious Right currently claims (and retrojects into the document), they might have a point.

Conservatives counter that no matter how unorthodox Thomas Jefferson was in regards to religion (he was, after all, the man who wrote the Jefferson Bible), he, along with the other founders, most certainly believed that God was the source of our human rights. But in that event, the word "God" becomes meaningless, because the God of Christianity (and Judaism, and Islam) grants no rights in the various scriptures. There are only bald assertions by a group of men coming out of the Enlightenment period that a vague fuzzy deist God established the rights, and this is held as a matter of unquestioned "self-evident" truth.

Other examples of non-Christian behavior include Washington, who would often get up and walk out of church rather than take Communion and who, contrary to his popular image, disappointed contemporary theologians with his lack of enthusiasm in preaching the Christian faith.[52]

At least one fundamentalist group, the Society for the Practical Establishment and Perpetuation of the Ten Commandments, recognizes that most of the Founding Fathers were not Christians in the sense that we would recognize them today. Of course, it then jumps to the conclusion that the Founding Fathers were inspired by Satan, that democracy is evil and ungodly, and that we should overturn the Constitution and replace it with a theocracy. QED.

Dispassionate unbiased outsider view[edit]

True-blue British patriot-imperialists regarded those rash and careless enough to sign up for Independence — regardless of their undoubted intellectual accomplishments and alleged religio-moral fiber — as self-evidently[citation needed] traitorous oath-breakers and disloyal criminal stirrers who fully deserved nothing less than getting strung up from the nearest tree.[53] (Which would undoubtedly have happened had not a visiting naval force of cheese-eating surrender-monkeys kept the British off the Continentals' backs by declaring war on the UK and tying up most of its army and navy overseas. Oh, and that time they saved the bacon of George Washington, the colonial so-called general, at Yorktown![]() in 1781.[54])

in 1781.[54])

See also[edit]

- Originalism, whose proponents give excessive weight on the Founding Fathers' conflicting and confusing opinions

External links[edit]

- Who Owns the Founding Fathers?, Tufts University

- "If The Founding Fathers Were Alive Today, They’d Be Too Fascinated By A Garbage Disposal To Do Anything", The Onion (of course)

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Later Johnson, Harvard College Library

- ↑ David McCullough brings 'John Adams' to life, CNN

- ↑ How Old Were the Leaders of the American Revolution on July 4, 1776?, Slate

- ↑ Address Accepting the Republican Presidential Nomination, UC Santa Barbara

- ↑ The Founding Fathers Fallacy. Penn Political Review.

- ↑ List of Founding Fathers

on Wikipedia

on Wikipedia

- ↑ Richard B. Morris in his 1973 book Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries.

- ↑ George Washington: The Commander In Chief. UShistory.org

- ↑ Constitutional Convention. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ 10 Facts About President Washington's Election

- ↑ Cooke, Jacob E. (2002). "George Washington". In Graff, Henry (ed.). The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed.). Scribner. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-684-31226-2.

- ↑ Randall, Willard Sterne (1997). George Washington: A Life. Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-2779-2. p. 484.

- ↑ Resistance and Punishment. Mount Vernon.

- ↑ The Philadelphia Gazette and Universal Daily Advertiser, May 24, 1796 [Oney Judge runaway notice].

- ↑ 10 Facts About Washington & Slavery

- ↑ The Confederation Series

- ↑ The Boston Massacre Trials. John Adams Historical Society.

- ↑ Ferling, John E. (1992). John Adams: A Life. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-08704-9730-8. p. 128–130

- ↑ Morse, John Torey (1884). John Adams. Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company. OCLC 926779205. p. 127–128

- ↑ On This Day: The first bitter, contested presidential election takes place. Constitution Center.

- ↑ Ferling, John E. (1992). John Adams: A Life. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-08704-9730-8. p. 333

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Alien and Sedition Acts.

- ↑ Congress Passes Socialized Medicine and Mandates Health Insurance -In 1798. Forbes.

- ↑ The tree of liberty... (Quotation). The Jefferson Monticello.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on A Summary View of the Rights of British America.

- ↑ The Declaration of Independence. PBS.

- ↑ Brewer, Holly (1997). "Entailing Aristocracy in Colonial Virginia: 'Ancient Feudal Restraints' and Revolutionary Reform". William and Mary Quarterly. 54 (2): 307–46. doi:10.2307/2953276. JSTOR 2953276.

- ↑ A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge. The Jefferson Monticello.

- ↑ 82. A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, 18 June 1779. National Archives.

- ↑ French Revolution. The Jefferson Monticello.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson: A Revolutionary World. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson: Architect of Indian Removal Policy. Indian Country Today.

- ↑ Wilentz, Sean (2005). The Rise of American Democracy. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 108–11. ISBN 978-0393058208. p. 138

- ↑ Jefferson's Attitudes Toward Slavery

- ↑ Feldman, Noah (2017). The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President. Random House. ISBN 9780812992755. p. 82–83

- ↑ Benjamin Franklin: America’s Inventor. History Net.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Pennsylvania Chronicle.

- ↑ What ‘Hamilton’ Forgets About Hamilton. New York Times.

- ↑ Ellis, Joseph J. (2004). His Excellency. Vintage Books. pp. 250–55. ISBN 978-1400032532.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 John Jay. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Jay Treaty.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Jay and Slavery. Columbia University.

- ↑ John Hancock and His Signature. National Archives.

- ↑ http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/five-myths-about-the-american-flag/2011/06/08/AG3ZSkOH_story.html

- ↑ As in, your third-party commentary?

- ↑ Read 'em all: The Federalist Papers and the Anti-Federalist Papers

- ↑ An Examination into the Leading Principles of the Federal Constitution, University of Chicago

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson Sneaks Back into Texas Textbooks, Good.is

- ↑ "Rand Paul's America", FrumForum

- ↑ FCC v. Pacifica, FindLaw

- ↑ The Declaration and the self-evident benefits of editing, FIU

- ↑ Waldman, Steven. Founding Faith: How Our Founding Fathers Forged a Radical New Approach to Religious Liberty. (Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 2009)

- ↑

Benjanmin Franklin apparently realised this, allegedly stating in all seriousness: "We must, indeed, all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately." He would have known what happened to the fellow-rebels and to the bones of Oliver Cromwell after the Restoration of 1660. Compare: Conway, Stephen (2002) [2000]. The British Isles and the War of American Independence (Reprint ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 142-143. ISBN 9780191542572. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

Isaac Fletcher of Cumberland expressed sharp criticism of the Americans in his diary, describing them as 'the enemy' and one of their army commanders as 'the rebell general'.[...] He concluded that the New Englanders were a 'wicked people', and hoped that they would feel the full force of God's wrath. [...] Some of the clergy of the church of England were still more critical of the colonists: 'If they were all put to the Sword, I will not condemn the Severity', wrote the Revd John Butler. [...] [T]he archbishop of York [...] was dubbed in one cartoon of the time as 'General Sanguinaire Mark-ham' for his advocacy of the most bloody means to put down the rebellion.

- ↑

Dull, Jonathan R. (2015) [1975]. The French Navy and American Independence: A Study of Arms and Diplomacy, 1774-1787. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. ix. ISBN 9781400868131. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

In the belief that military history is an essential component of diplomatic history I have studied the French navy as the means by which French diplomacy won its greatest (and most costly) victory of the eighteenth century, the achievement of American independence.