George Orwell

| How an Empire ends U.K. Politics |

| God Save the King? |

“”Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.

|

| —"Why I Write" (1946)[1] |

Eric Arthur Blair (alias George Orwell, 1903—1950) was a dirty atheist[note 1] socialist is perhaps the most famous anti-authoritarian author. Many ideas and phrases from his novels have entered the English lexicon — especially "Big Brother is watching you" (1984)[2] and "some animals are more equal than others" (Animal Farm).[3] As such, Orwell has become one of those figures, like Jesus Christ and Ronald Reagan, whom people invoke when they want to win an argument without any effort.

Politics

Despite numerous attempts by conservatives to claim the literary hero as one of their own,[note 2][4][5] Orwell was staunchly leftist. Orwell was one of many left-wing writers and journalists who fought against Franco's Falangists as a member of the Trotskyist POUM militia,![]() as he recorded in his memoir Homage to Catalonia — giving him a sneak peek into both fascism and the war to come. His experience in the successful anarcho-syndicalist communes in Catalonia also heavily influenced his views regarding both socialism and individual liberty.

as he recorded in his memoir Homage to Catalonia — giving him a sneak peek into both fascism and the war to come. His experience in the successful anarcho-syndicalist communes in Catalonia also heavily influenced his views regarding both socialism and individual liberty.

That said, he was already not enamored with communism before his stint in the Spanish Civil War. During the war, he witnessed brutal suppression of the anarchists, trotskyists, and various other left factions in the war, committed by the USSR-backed Marxist-Leninist (i.e. Stalinist) faction against their own allies. He returned as an utter anti-Stalinist and as an advocate of democratic socialism. To that end, at one point he created and provided a list![]() to the Labour Party government of people he suspected of being Soviet infiltrators. His negative view of Stalinism influenced his two best-known novels; Animal Farm is an obvious allegory for Stalin's Soviet Union and Nineteen Eighty-Four, which also criticizes fascism and imperialism. Indeed, Orwell stated that every single piece of “serious work” that he wrote since 1936 was written in support of libertarian socialism and against totalitarianism.[6]

to the Labour Party government of people he suspected of being Soviet infiltrators. His negative view of Stalinism influenced his two best-known novels; Animal Farm is an obvious allegory for Stalin's Soviet Union and Nineteen Eighty-Four, which also criticizes fascism and imperialism. Indeed, Orwell stated that every single piece of “serious work” that he wrote since 1936 was written in support of libertarian socialism and against totalitarianism.[6]

Despite his fervent and overt leftism, as well as his critique of the authoritarianism of the USSR, he is frequently claimed by capitalists and various other right-wingers as being one of their own. While it is reasonable for many to be unfamiliar with Orwell’s actually stated political views, even his most famous anti-Stalinist works heavily critique capitalism at the same time. For example, the end of Animal Farm presents the final corruption of the pigs as being the complete reversion of the state to human-style domination — in other words, the ultimate evil of the communists is that they are simply another form of capitalist. Furthermore, 1984 does not present capitalism and imperialism in a particularly favourable light either. This is most apparent with “The Theory and Practice of Oligarchal Collectivism” by Emmaual Goldstein — the mythical underground resistance book that (supposedly) describes the fundamental structure of the world of 1984. The book is an overt metaphor for Trotsky’s writings on both capitalism and the USSR, and describes the fundamental brutality of the preceding capitalist world and how its structures and mechanisms caused the totalitarian government of 1984 to be essentially inevitable. While the reliability of this work is never fully established, with many considering it to be a parody of Trotsky’s works such as “The Revolution Betrayed”,[7] and the Party itself claiming authorship,[8] it is also worth considering that the fundamental arguments in the book very closely match Orwell’s actual critiques and perspectives of both capitalism and the Soviet Union.

Orwell's ideas on Britishness and socialism still resonate today, more than 60 years after his death; indeed John Major, the 1990s Conservative Prime Minister, quoted him once when attempting to define what was worth preserving in the country:[9]

He was… an eloquent eulogist of England – John Major's vision of warm beer, cricket on the village green and a redoubtable maiden aunt bicycling to morning communion through the mist was borrowed from Orwell.

Animal Farm (1945)

“”The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

|

| —Animal Farm[3] |

Animal Farm[3][note 3] is a novella about an insurrection of farm animals against the human owner of the farm. Its plot is a loose (and thoroughly transparent) allegory of the October Revolution, the overthrow of the Tsar and rise of communism in the Russian Empire (and from 1922, the USSR), its eventual betrayal and usurpation by Joseph Stalin, and the atrocities committed in communism's name.

Orwell's novel serves as a critique of totalitarianism in general, portraying how the revolution was consumed by sinister forces (and also displaying the inherent weaknesses in the primitive body politic that allowed such a brazen seizure of absolute power). If we were to speculate on any character in the novel based on Orwell, it's probably the wise old donkey who refused to get caught up in the revolutionary bandwagon in the first place.

Characters and symbolism

Most characters in Animal Farm personify (or animal-ify) people of the 1930s-40s Soviet Union, with a few exceptions.

- Humans (capitalists, royalty):

- Mr. Jones, the drunken old farmer, represents Tsar Nicolas II, who was overthrown in the February Revolution. The Return of Jones and the Battle of the Cowshed represent the October Revolution.

- Mr. Pilkington is a neighbor farmer and the owner of Foxwood, which represents the British Empire.

- Frederick is another neighboring farmer and the owner of Pinchfield. He represents Adolf Hitler, his farm being Nazi Germany. The sale of wood to Frederick represents the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (the signing of which immediately preceded World War II), and the fact that the banknotes were counterfeit represent the insincerity of the pact and the German invasion of the USSR in 1941.

- Mr. Whymper comes to Animal Farm weekly and deals with Napoleon, providing the pigs whiskey in exchange for various things, such as eggs and Boxer. He represents capitalists who did business with the Soviet Union.

- Pigs (communist party members): Vladimir Lenin is notably absent. His role and personality are divided between Old Major, Napoleon and Snowball.

- Old Major is most easily interpreted as Karl Marx. An old stud boar, he forms the philosophy of Animalism, an allegory of communism. Old Major is personified as Marx through his original prophecy of an animal utopia at the beginning of the book, and his character later also alludes to Vladimir Lenin, as Old Major's skull is preserved and saluted by the animals of the farm weekly after the revolution, while Lenin's body was also preserved after his death.

- Napoleon represents Stalin; he is the dictator of Animal Farm and turns it into a dystopia via power and propaganda in much the same way Stalin did. He also holds general mannerisms which were attributed to Stalin: manipulative, arrogant, cruel, backstabbing, and corrupt with power. He also tries to get animals to acquire guns to protect themselves, which can be seen as Stalin's "Socialism in One Country" policy.

- Snowball's ousting and subsequent demonisation is based on Leon Trotsky, who was banished from the Soviet Union in 1929. Snowball can also be seen as a larger personification for general enemies of the Soviet Union under Stalin. He also advocates for sending out doves to spread the message, similar to Trotsky's "Pernament Revolution" theory.

- Squealer is a personification for the Soviet Union's use of propaganda, as he is seen several times throughout the book justifying the power abuse by the pigs, and is once caught altering the Commandments of Animal Farm, though this is lost on most of the animals there. He is based on Vyacheslav Molotov and Pravda magazine (not the current incarnation of Pravda which is at least as bad).

- Horses (workers):

- Boxer, the horse, is the strongest animal on the farm. He represents the masses of Soviet workers who loved Stalin and the Soviet Union — dedicated to his job but slightly dimwitted and willing to take anything that Napoleon says as gospel. When Boxer is wounded by Frederick's invasion of Animal Farm and can no longer work, Napoleon sells him to be turned into glue and bonemeal, so that Napoleon can buy another case of whiskey. This represents Stalin's betrayal of the workers. Boxer's motto, "I will work harder", may be a callback to the Stakhanovite movement.

- Clover is "a stout motherly mare approaching middle life, who had never quite got her figure back after her fourth foal." She is simple but not stupid. She never learned to read, but noticed the change in the commandments, and she was the one who persuaded Benjamin to read the final version out loud. It may be inferred that Benjamin would not have done that for anybody but her.

- Molly: A pretty but vain and foolish white mare. She's disappointed that there is no one around to give her ribbons or sugar after Farmer Jones is overthrown, so she flees to a neighbouring farm controlled by humans. Molly is an allegory of the decadent capitalists who fled the USSR after the overthrow of the monarchy.

- Boxer, the horse, is the strongest animal on the farm. He represents the masses of Soviet workers who loved Stalin and the Soviet Union — dedicated to his job but slightly dimwitted and willing to take anything that Napoleon says as gospel. When Boxer is wounded by Frederick's invasion of Animal Farm and can no longer work, Napoleon sells him to be turned into glue and bonemeal, so that Napoleon can buy another case of whiskey. This represents Stalin's betrayal of the workers. Boxer's motto, "I will work harder", may be a callback to the Stakhanovite movement.

- Other animals:

- Benjamin is a donkey and one of the most intelligent animals on the farm. He can read and clearly sees what is going on. He keeps his thoughts to himself, ensuring his survival. Clover persuades him to read the final version of the commandments out loud, breaking his habit. Benjamin can be assigned to a variety of real characters, but there are probably always people like him in any revolution.

- The dogs, raised by Napoleon and used as his enforcers, are clearly the Soviet secret police (first known as the Cheka, later the NKVD and finally the KGB

).

). - The sheep of the farm are an allegory for the general public of the Soviet Union, with their bleating of the short Animalist slogan, "Four legs good, two legs bad", and their increased willingness to follow whatever the leadership says; in particular, they are later taught to bleat, "Four legs good, two legs better" instead. See "sheeple".

Commandment(s) of Animalism

After the overthrow of the humans, the pigs reveal their work on the concept of Animalism by painting the "Seven Commandments of Animalism" on the wall of the main barn — the original rules by which the animals of Animal Farm were to live by.

- Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy.

- Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend.

- No animal shall wear clothes.

- No animal shall sleep in a bed.

- No animal shall drink alcohol.

- No animal shall kill any other animal.

- All animals are equal.

The sheep of the farm, being too thick to remember all of these, had their rules reduced to "Four legs good, two legs bad!" which they bleated at random — enough to piss anyone off. However, with the corrupting effects of absolute power the pigs amended the Commandments to excuse their own excesses; so that:

- No animal shall sleep in a bed with sheets.

- No animal shall drink alcohol to excess.

- No animal shall kill any other animal without cause.

Ultimately, Napoleon simply decides to get rid of all the Commandments in a final dictatorial move against the animals, replacing them with but one commandment:[note 4]

- All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

Plot (Major spoiler warning!)

The plot centres around a group of animals on the Manor Farm, owned by an incompetent drunk named Mr. Jones. The story starts with the boar Old Major calling a meeting in the main barn, in which he tells the other animals of a dream he had the previous night. In the dream, he sees a land where animals are no longer owned and exploited by humans. Old Major then teaches the animals a related song he remembered from his youth, entitled "Beasts of England". The animals are heartened by the thought of a day when they can work for themselves rather than the humans, and after Old Major dies a few nights later, the pigs of the farm, depicted as the smartest creatures, begin to plan for the revolution, which occurs some months later.

Immediately after the revolution, the farm is renamed "Animal Farm," and seven commandments are instigated by the pigs which dictate the ruling political ideology of "Animalism." As the story develops, the pigs increasingly abuse their power over the oblivious animals. Napoleon and Snowball compete for power, with Snowball announcing a plan to improve the farm by building a windmill. Threatened, Napoleon orders his dogs to chase Snowball off the farm and begins accusing him and any of his previous supporters of being enemies. Napoleon later moves into the farmhouse, sleeps in Mr. Jones's bed, drinks his alcohol, and even begins wearing his clothes, all while continually cutting rations for the animals in the farm. As the windmill is constructed, it is damaged by a storm, and Napoleon convinces the other animals that Snowball is sabotaging their project. The pigs begin a series of purges to root out Snowball's collaborators where certain animals break down and confess to treasonous crimes. They are later killed.

The pigs also begin to trade with humans for supplies, and Animal Farm is understood to be "at war" with one or two of the neighboring farms, over their alleged harboring of Snowball — whichever farm he was supposedly hiding in was the farm Animal Farm considered the enemy. In order to justify their wacky antics, the pigs alter the Seven Commandments under cover of night to fit in with their obvious breaking of them — this is revealed to the other animals when the pig Squealer is found injured with a bucket of paint at the wall of the Seven Commandments, although few of the animals were able to make sense of it.

Mr. Frederick, one of the neighboring farmers, attacks Animal Farm and uses a bomb to destroy the windmill. The animals drive him away, but many of them are wounded, including Boxer the hardest working horse. Despite this, Boxer works himself harder and harder to rebuild the windmill until his body breaks down completely. Napoleon sends for a van to take Boxer to a veterinarian, but Benjamin the donkey notices that it belongs to the local knacker instead. It turns out that Napoleon had sold Boxer to be killed and processed into animal glue in exchange for more whiskey. Later, Squealer announces that Boxer sadly died in the hospital.

The book ends with the pigs one day emerging from the house dressed in human clothes carrying whips. The final scene is of the animals watching Napoleon and the pigs one night in Jones's house, as they drink beer and play cards with the humans from the neighboring farms as friends. The humans commend Napoleon on his exploitation of the animals while Napoleon accepts the humans' friendship, blaming any previous indiscretions on "saboteurs". He announces that the name of the farm is to be changed back to its original name of "Manor Farm" and that the animals will no longer be allowed to address each other as "comrade." All is well until a fight breaks out with both Mr. Pilkington and Napoleon playing the Ace of Spades simultaneously, leaving the animals standing outside, unable to tell the difference between either.

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

| —O'Brien, Nineteen Eighty-Four[2] |

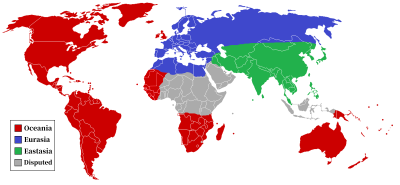

Nineteen Eighty-Four is a dystopian novel set in 1984.[note 5] It tells the tale of a nightmarish future totalitarian state through one helpless man's struggle to hold on to his humanity. It is set in a world where, at least as far as anyone knows, three warring superstates called Oceania (British Empire+North&South America+Australia), Eurasia (Soviet Union+Europe), and Eastasia (China+Japan) exist and have always existed. These three superstates dominate more than 75% of the Earth's surface and fight an ongoing and inconclusive three-way war with constantly shifting alliances, with neither one having an advantage over the other and none able to conquer the other. The old colonial lands of Africa and South Asia are largely ignored, except as meaningless territorial gains. It follows the story of a London bureaucrat named Winston Smith, a propaganda writer for the "Ministry of Truth", as he attempts to make a change, however small, in the opaque and brutal government of "Big Brother", concluding in his betrayal by a Party double agent and his breakdown under torture and brainwashing.

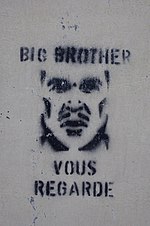

Several phrases coined in the book have entered popular culture[note 6] and common use, most notably "Big Brother (is watching you)," but also the Two Minutes of Hate, doublethink, Thoughtcrimes/Police, Newspeak, and, perhaps unfairly to the memory of Orwell, "Orwellian" as a synonym for totalitarian. Big Brother in particular is a watchword for privacy rights on both sides of the political aisle.

Background

Written in 1948, the book is an obvious critique of the Stalinist U.S.S.R. (Nineteen Eighty-Four's Ingsoc, or "English Socialism" was imagined as a technologically-advanced development of Stalinism). Although many readers miss the references[citation needed], the book also critiques fascism and imperialism. Both were much more present in memory in 1948 than in subsequent decades. Thus the Thought Police is a reference to the Japanese Thought Police (the Thought Section of the Criminal Affairs Bureau)[10] and Oceania is unmistakably Winston Churchill's Union of the English-Speaking Peoples (an Anglo-Saxon pan-nationalism that would have seen the United States take responsibility for the British Empire). Orwell understood the evils of British imperialism because he was raised in India and served in Burma.

"Orwellian"

“”If you're able to vocally decry an action as Orwellian, it isn't.

|

| —Reddit user /u/GearyDigit[11] |

The adjective "Orwellian" has come to mean "authoritarian", "tyrannical", or "dystopian" — to such an extreme degree as for Orwellian authorities to wish to control reality itself.[note 7]

One of the most important and chilling elements in Nineteen Eighty-Four is Orwell's portrayal of how the ruling Party places no boundaries on its efforts to subjugate its people. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Party:

- encourages doublethink, to obfuscate reality and to prevent questioning of the Party

- punishes thoughtcrime, to prevent anyone from overcoming doublethink

- manipulates language through Newspeak, to require doublethink in all language

- spreads propaganda and alters historical narratives, continually re-writing history through negationism and pseudohistory, to make doublethink unnecessary and the Party appear inherently good

- encourages borderline-worship of the Party, or "Big Brother", to reinforce doublethink

- creates a constant foreign threat of war to unite the populace in support of the Party

- monitors all citizens through sophisticated surveillance equipment, to ensure compliance

- detains, tortures and murders noncompliant citizens

An Orwellian name is a name an organisation gives itself while actually engaging in the opposite activity from what the name suggests. It was apparently distinctive of the Communist groups Orwell critiqued, such as "Operation Trust"[12] or "The Hundred Flowers Campaign".[13]

Examples of Orwellian regimes include North Korea and DAESH territory.

"Doublethink"

"Doublethink" describes the act of simultaneously but separately believing in two contradictory concepts. To practice doublethink, a person must "deny the existence of reality" while taking into account "the reality that one denies…"[14] It could be summarized as simultaneously accepting and rejecting a given proposition.

Orwell described doublethink as a "labyrinthine world" where one believes one thing while doing or saying the exact opposite. The very act of practicing doublethink requires a person to employ doublethink — i.e., even though you know doublethink exists, you must deny the existence of doublethink in order to use doublethink. This contradictory concept is at the core of what are now called "Orwellian" social structures.

Real life examples of doublethink can be found in folks like Biblical fundamentalists. They will insist that Genesis be taken completely at face value, but then when they get to the Song of Solomon, which would support sex for sex's sake when taken at face value, they insist it's just a metaphor for God's love for humanity (members of the Religious Right tend to give this same treatment to passages where Jesus does things like advocate that the rich give money to the poor). Other examples include Neo-Nazis (denying the holocaust one second and then advocating that all white people "finish the job" on the jews the next), flat earthers (insisting that everyone "trust their own eyes" one second and then pulling out terms like "perspective" and "camera trickery" when presented with photographic evidence of the round earth) and others. Doublethink could therefore be thought of as cognitive dissonance that not only remains unresolved but is also desirable to leave unresolved.

"Thoughtcrime"/"Crimethink"

“”What person would proclaim themselves in favor of "force and fraud"? One of the little tricks Libertarians use in debate is to confuse the ordinary sense of these words with the meaning as "terms of art" in Libertarian axioms. They try to set up a situation where if you say you're against "force and fraud", then obviously you must agree with Libertarian ideology, since those are the definitions.

|

| —Seth Finkelstein[15] |

In the novel, the government attempts to control the thoughts of its citizens, as well as their actions. "Thoughtcrime" is the only type of offence recognised by the Ingsoc government and the punishment is the same regardless of the actual nature of the offence. In his diary, Winston Smith writes that "Thoughtcrime does not entail death. Thoughtcrime is death." Newspeak was developed to effectively make thoughtcrime impossible. The Newspeak for thoughtcrime is "crimethink". Thoughtcrime has become an incredibly influential concept in current political discourse, and the word is often used by those opposing censorship, perceived or otherwise, of a particular viewpoint. It's also frequently invoked as a criticism of hate crime laws, which is a dishonest representation of the intent and content of those laws. After all, the punishment is not for "thinking bad things" but for actually and actively inciting hatred and/or committing violence against others. In the latter case, the hate crime motive is simply seen as an aggravating circumstance meriting harsher punishment of what is already a criminal offence (much like how punishment for murder can be harsher if the murder was premeditated, or how punishment for drug possession can be harsher if the drugs were intended to be sold).

"Newspeak"

“”As societies grow decadent, the language grows decadent, too. Words are used to disguise, not to illuminate, action: you liberate a city by destroying it. Words are to confuse, so that at election time people will solemnly vote against their own interests.

|

| —Gore Vidal |

"Newspeak" is a language that appears in Nineteen Eighty-Four. Designed by the ruling Ingsoc regime, its purpose is to suppress thought by severely curtailing both the conceptual vocabulary and permissible grammatical structures of Oldspeak. As Orwell describes in the Appendix: "…a thought diverging from the principles of Ingsoc should be literally unthinkable, at least insofar as thought is dependent on words."[16] The ultimate goal of implementing Newspeak by the Party is to reduce language to its most basic function of simple communication and destroying individual human expression by elimination of antonyms and synonyms, near eradication of adjectives and adverbs, and making amplifiers and negations as simple prefixes (i.e. "doubleplusgood" meaning "great" and "doubleplusungood" meaning "awful".)

This idea of totalitarianism taken to its logical extreme is deeply unsettling, not least for its immediate, intuitive plausibility. As with many of the novel's terms and ideas, it captured the popular imagination and has passed into modern political and cultural discourse, to be variously used, abused and confused by individuals right across the political spectrum.

Orwell's description of Newspeak is imperfect,[note 8] but in essence he imagines language distilled to a brute functionality. Basic needs can be expressed, but beyond this, the available vocabulary is so radically compressed as to prohibit anything other than the most perfunctory description or evaluation of any given object, term or concept.

This compression is achieved by breaking down the distinction between the different parts of speech, so that all remaining words can act as both nouns and verbs. Adjectives and adverbs are formed from these noun-verb roots with the addition of -ful and -wise, respectively. Orwell offers the example of the verb to cut, purged as its meaning is sufficiently contained within the new noun-verb knife.[17] By extension, this would lead to the elimination of verbs such as stab, slash, slice, and carve. Knifeful could replace adjectives as diverse as sharp, cutting, pointed, piercing and incisive.

Grammatically, Newspeak is simplified to an almost infantile, pre-literate degree. Irregular verb forms are suppressed (e.g. got, ran, slept = getted, runned, sleeped) and any word can be negated with the prefix un-, (e.g. good : bad = good : ungood, and presumably unknifeful would mean blunt) allowing the further eradication of hundreds of words. Emphasis is added with the modifiers plus- or doubleplus-, hence perhaps the most famous Newspeak formulation: doubleplusungood (meaning "really really bad").[note 9]

"Doublespeak"

Doublespeak is a neologism used to describe language that is deliberately intended to conceal meaning; for example: enhanced interrogation interviewing techniques used in a sentence to supplement the word torture. The term is not actually from Orwell's novel, but is instead an extra-canonical portmanteau of "doublethink" and "newspeak." Two common forms of doublespeak are euphemisms and management speak.

Misuse

Newspeak has since become a term for any language that is controlled or abused in the name of political power. Some people have compared some politically correct terminology to Newspeak — this is almost universally critical, comparing unfavorably with the totalitarianism expressed in Nineteen Eighty-Four, the logic is usually that people who push such terminology are oppressively limiting speech. This is inaccurate though, as most proponents of so-called "politically correct" terminology as not proposing to restrict speech through government action and are not supporting the use of such terminology as a tool of social control. Rather "political correct" terminology is based on the notion that certain terms might be offensive to certain groups due to how such terms were employed in the past as tools of social control and that our civil society is best served when we attempt to not offend each other as much as is practicable.

Words that describe prejudice have been compared to Newspeak. In the case of homophobia, for example, a word has been added to describe a new feeling and attitude that specifically demeaned homosexuality unfairly and unjustly. Arguably this trend continued with the addition of heterophobia — although this is really just be a right-wing re-branding of gay rights rather than a new concept. The purpose of Newspeak, however, was to reduce the number of words in the language, thus removing the ability to express new feelings or attitudes (that this probably wouldn't work in reality is not the issue). Adding words is therefore the opposite of Orwell's original Newspeak — it enables new thoughts to be expressed with new words.

Another example of creeping Newspeak is the relentless "positive thinking" tendency which has virtually purged the word "problem" from English (and other languages) in favour of the less overtly negative "challenge". This particular style of language is especially prevalent in management and PR circles.

"Crimestop"

"Crimestop" is one of Newspeak's less well known concepts, but perhaps the most pertinent (and funny) when discussing the various stripes of fundamentalism. It denotes a learned mental discipline: a conditioned inability even to grasp thoughts contrary to one's own belief system. Orwell writes:[18]

"Crimestop means the faculty of stopping short, as though by instinct, at the threshold of any dangerous thought. It includes the power of not grasping analogies, of failing to perceive logical errors, of misunderstanding the simplest arguments if they are inimical to Ingsoc, and of being bored or repelled by any train of thought which is capable of leading in a heretical direction. Crimestop, in short, means protective stupidity."

"Big Brother" / "Thought Police"

"Big Brother" is a terrible reality TV show the embodiment of the totalitarian state. In theory, Big Brother is always watching the populace and controls their every move. In practice, Big Brother functions like Bentham's Panopticon![]() — Big Brother isn't always watching. In fact, most of the time, Big Brother is not watching. But Big Brother has set up a system where Big Brother can always watch, but you will never know when Big Brother is watching. This omnipresent surveillance has a chilling effect — even though Big Brother isn't always watching, you behave as if they were every second... because they really might be. If The thought police even suspect you of thoughtcrime, they send you to the Ministry of Love (or "MiniLuv" in Newspeak) where they torture you until you submit to their brainwashing.

— Big Brother isn't always watching. In fact, most of the time, Big Brother is not watching. But Big Brother has set up a system where Big Brother can always watch, but you will never know when Big Brother is watching. This omnipresent surveillance has a chilling effect — even though Big Brother isn't always watching, you behave as if they were every second... because they really might be. If The thought police even suspect you of thoughtcrime, they send you to the Ministry of Love (or "MiniLuv" in Newspeak) where they torture you until you submit to their brainwashing.

In the novel, the "Thought Police" are agents of Big Brother's totalitarian government.

"Memory hole"

“”Who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.

|

| —Nineteen Eight-Four, George Orwell[19] |

"Memory hole" is a neologism that refers to ... uh ....

The term comes from George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four where "memory hole" refers to a file transfer system that leads to an incinerator. Since all texts that contradict the Party's take on history are disposed of, citizens have no evidence that the government has ever been wrong. So the government can rewrite history however it wants.[20]

Today the term is used metaphorically for when people (most often politicians) carry on as though a certain event in the past lacks historicity. Examples are attempts to gloss over the Three-Fifths Compromise![]() or ignore certain past atrocities like the Holodomor. A more modern example is Ben Carson on his supplement-peddling past and the general unwillingness to call him out on it.

or ignore certain past atrocities like the Holodomor. A more modern example is Ben Carson on his supplement-peddling past and the general unwillingness to call him out on it.

Were you there? Minitrue version

Nineteen Eighty-Four contains a critique of the reasoning used by some Young Earth Creationists: Were you there?.[21]

O'Brien

“”'Now I will tell you the answer to my question. It is this. The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power. Not wealth or luxury or long life or happiness: only power, pure power.

|

O'Brien, the main antagonist of the novel and a member of the Thought Police, serves as the voice of the ideology of the Party. After capturing Winston, he tortures for an indeterminate amount of time within the walls of the Ministry of Love. While torturing him, O'Brien reveals to Winston why the Party resorts to totalitarian control of the people and their goals for the future of humanity. He tells Winston that the Party seeks to destroy individual identity, where people merge their individuality into the identity of the Party. In their minds, to escape the mortality of human life, the Party acts as the immortal avatar of human existence. To the Party, nothing even exists outside it. They resort to solipsism methods in order for people to doubt the reality around them and to further give away their identity to the Party (O'Brien refers to this as "collective" solipsism). Their brainwashing is so destructive that they can even make people believe that Party members can levitate or turn invisible. It is even suggested that O'Brien had been converted from this kind of torture ("They got me a long time ago."- Part 1, Chapter 1) though it's unclear whether this is the truth or an exaggeration. All of this is to serve one purpose: to control every aspect of experienced reality, or at least the perception of experienced reality.

“”Power is in inflicting pain and humiliation. Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing. Do you begin to see, then, what kind of world we are creating? It is the exact opposite of the stupid hedonistic Utopias that the old reformers imagined. A world of fear and treachery is torment, a world of trampling and being trampled upon, a world which will grow not less but more merciless as it refines itself. Progress in our world will be progress towards more pain. The old civilizations claimed that they were founded on love or justice. Ours is founded upon hatred. In our world there will be no emotions except fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement. Everything else we shall destroy -- everything. Already we are breaking down the habits of thought which have survived from before the Revolution. We have cut the links between child and parent, and between man and man, and between man and woman. No one dares trust a wife or a child or a friend any longer. But in the future there will be no wives and no friends. Children will be taken from their mothers at birth, as one takes eggs from a hen. The sex instinct will be eradicated. Procreation will be an annual formality like the renewal of a ration card. We shall abolish the orgasm. Our neurologists are at work upon it now. There will be no loyalty, except loyalty towards the Party. There will be no love, except the love of Big Brother. There will be no laughter, except the laugh of triumph over a defeated enemy. There will be no art, no literature, no science. When we are omnipotent we shall have no more need of science. There will be no distinction between beauty and ugliness. There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always -- do not forget this, Winston -- always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face -- for ever.

|

This is what power is to the Party, complete and utter control of everything. A truly nightmarish view of a future dominated by authoritarian order and totalitarian control of society. While Orwell was critiquing the Stalinist Soviet Union in his time, his warning stands the test of time — and in a very special part of the globe it sadly is still very much relevant.

Criticism

Despite (or because of) his importance to the left and democratic socialism, Orwell has been accused of many things. Often this is to discredit him or his followers; for instance the Daily Mail was inspired in 2018 to ask "Was George Orwell just a dirty old man?", combining criticism of Orwell (who it mentions would probably oppose Brexit) with an attack on modern wokeness. The subtext is that the left has no right to invoke Orwell if it cares about women's rights, but the accuracy of his vision of totalitarianism is unrelated to how many prostitutes he visited.[22]

Antisemitism

Orwell has been accused of antisemitism by figures as varied as Christopher Hitchens and Malcolm Muggeridge![]() . The charge is chiefly levelled at his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London. Hitchens suggested that Orwell was prejudiced by virtue of his upbringing and tried to overcome this:

. The charge is chiefly levelled at his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London. Hitchens suggested that Orwell was prejudiced by virtue of his upbringing and tried to overcome this:

One of the many things that made Orwell so interesting, was his self-education away from such prejudices, which also included a marked dislike of the Jews. But anyone reading the early pages of these accounts and expeditions will be struck by how vividly Orwell still expressed his unmediated disgust at some of the human specimens with whom he came into contact. When joining a group of itinerant hop pickers he is explicitly repelled by the personal characteristics of a Jew to whom he cannot bear even to give a name, characteristics which he somehow manages to identify as Jewish.[23]

Throughout his literary career, Orwell was fond of identifying people as Jewish, which isn't necessary or normal in most situations. However during and after World War Two, Orwell advocated for Jewish refugees and migrants, and if (as Hitchens says) he condemned his own antisemitism, he also denounced antisemitism in others.[24]

Homophobia and misogyny

Hitchens also noted a homophobic tendency, with remarks about "nancy" homosexuals, but suggests Orwell also tried to overcome this prejudice.[23]

Much of his work has a misogynistic strain, although there is the caveat that he is writing fiction about imaginary characters. Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four is misogynistic, initially expressing a desire to rape Julia, and is generally contemptuous of her and obsessed with physical details rather than her mind.[25] Keep the Aspidystra Flying is about the danger women and domesticity pose to the creative process and the heroic male intellect, with a protagonist just as contemptuous of women as Smith is.

Orwell was accused of trying to rape a childhood friend, Jacintha Buddicom, according to Buddicom's cousin Dione Venables, in a postscript to Buddicom's memoir Eric & Us. In 1921 when Buddicom was about 20, Orwell left her with a ripped skirt and bruise on her hip.[26][27] However we only have Venables' account as Buddicom herself doesn't seem to have viewed it as attempted rape.

Orwell's list

In 1948 he gave the British government a list of prominent people whom he suspected of communist sympathies. This has attracted a range of interpretations: some see it as a great betrayal both of friends and political progressives, while others note that Orwell carrying out a simple practical task in providing the British government's propaganda department with a list of people who would be unsuited for employment writing anti-Communist propaganda.[28]

Truthfulness of his work

There is debate about the accuracy of some of his reportage. This goes back to the early essay "Shooting an Elephant", although if it's true and the young Orwell/Blair did shoot an elephant for no good reason, Orwell is hardly describing himself in flattering terms, and if he's lying and didn't shoot an elephant, good for him.[29]

Misuse of Orwell's work

Many arguments for leftist socioeconomic policy have been argued against as being "Orwellian", while, ironically, Orwell himself was a leftist and a democratic socialist, fighting for the socialist POUM in the Spanish Civil War, and later expressing admiration for the anarchist CNT/FAI. He even wrote a book about it, Homage to Catalonia. Even more ironically, Orwell spoke against the obfuscation of language and was particularly opposed to people using precise terms in the wrong context, yet "Orwellian" has been applied to even the most benevolent of world leaders.

It has become popular to use the book as an attack on socialism in general (as opposed to the totalitarian regimes of the communists), while ignoring the fact that Orwell himself was a committed socialist.

Historical presentism and failure to understand the breadth of Orwell's political denunciation has meant poorly informed criticism of the work.[citation needed] However, science fiction author Isaac Asimov wrote a particularly scathing attack on the book for being uncreative and overly focused on communism while failing to criticize other forms of authoritarianism.[30]

Nineteen Eighty-Four is particularly beloved by conservatives because of its supposed applicability to the issue of political correctness. This rather flies in the face of Orwell's political beliefs, and his opinions on the extreme form of totalitarianism known as Stalinism was formed by his experiences fighting in the Spanish Civil War as a foreign irregular.[31]

Other works

Orwell's work on other topics is also notable:

- Down and Out in Paris and London (1933):[32] Exposes the unsanitary and rough working conditions in France's fine restaurants and in Britain's homeless shelters.

- Burmese Days (1934):[33] Recounts Orwell's work as a policeman in Burma and criticizes British imperialism.

- Shooting an Elephant (1936): Another (possibly fictional) examination of colonial politics.

- The Road to Wigan Pier (1937):[34] Continues the theme of Down and Out. Details the conditions of workers in the north of England. Advocates for a broad-tent form of socialism that did not exclude workers or the lower middle class.

- "A Nice Cup of Tea" (1946): Sage advice on the proper preparation of tea.[35]

Adaptations

- Animal Farm:

- A 1954 animated version by the UK studio Halas and Batchelor

, which was secretly financed by the CIA.[36]

, which was secretly financed by the CIA.[36] - A 1999 live-action/CGI version for the TNT Network

(later released on home video), produced by Hallmark Entertainment with special effects by Jim Henson's Creature Workshop.[37]

(later released on home video), produced by Hallmark Entertainment with special effects by Jim Henson's Creature Workshop.[37]

- A 1954 animated version by the UK studio Halas and Batchelor

- 1984:

- A 1953 broadcast of CBS's Westinghouse Studio One series

- A 1954 broadcast for the BBC.

- A 1956 feature film directed by Michael Anderson.

— this film was also funded by the CIA and included two endings, one intended for the UK audience and one for the US audience.[38][39]

— this film was also funded by the CIA and included two endings, one intended for the UK audience and one for the US audience.[38][39] - A 1984 feature film directed by Michael Radford with all dates and locations as written in the original book.

(That is, when Winston Smith writes "April 4, 1984" in his diary, it really was filmed on that date.)

(That is, when Winston Smith writes "April 4, 1984" in his diary, it really was filmed on that date.) - A 2001 opera by Lorin Maazel

- A 2014 play by

DavidRobert Icke and Duncan Macmillan - Several radio adaptations (NBC University Theatre in 1949, Theatre Guild on the Air in 1953, and the BBC in both 1954 and 2013).

- An incomplete graphic novel. Chapter 1[40] and 2[41]

- The country of North Korea.

- A 1953 broadcast of CBS's Westinghouse Studio One series

See also

External links

- Biography and works online

- "Taking Liberties": Documentary film showing the loss of civil liberties in the United Kingdom and an alleged encroaching of a Big Brother state on YouTube

Notes

- ↑ We're exaggerating on that one; he was an atheist who held a humanist view, but also still attended Anglican services and took Communion.

- ↑ Claiming Orwell is a popular right-wing sport in America, like hunting for baby seal pelts.

- ↑ Animal Farm was published in August 1945 in England (originally named Animal Farm: A Fairy Story) and in 1946 in North America, with "A Fairy Story" being dropped from the title. See A Note on the Text, Peter Davison, 2000.

- ↑ Also the most well-known phrase of the book.

- ↑ No, really.

- ↑ One of a zillion examples: See the Wikipedia article on Room 101 (disambiguation)., or less surprisingly, the TV Tropes article named after it.

- ↑ Of course, Orwell himself probably wouldn't have liked his name being used in this sense

- ↑ It would have been an immense (and somewhat anal) undertaking to realise his vision completely, and completely unnecessary for the purposes of the novel.

- ↑ It is conjectured that, since Orwell had a bad experience with Esperanto in 1927, he gave Newspeak a simplistic grammar and vocabulary as a kind of "take that" against Esperanto's deliberate use of these concepts.

References

- ↑ http://orwell.ru/library/essays/wiw/english/e_wiw

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.online-literature.com/orwell/1984/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/o/orwell/george/o79a/complete.html

- ↑ http://harpers.org/archive/1983/01/if-orwell-were-alive-today/

- ↑ http://www.lewrockwell.com/rothbard/rothbard32.html

- ↑ "Why I Write", The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, 1 – An Age Like This 1945–1950, Penguin, p. 23

- ↑ Decker, James M. (2009). "George Orwell's 1984 and Political Ideology". In Bloom, Harold (ed.). George Orwell, Updated Edition. Infobase Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-4381-1300-5.

- ↑ Orwell, George Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) in the omnibus George Orwell (1980) Book Club Associates London, p. 894

- ↑ http://www.arlindo-correia.com/141103.html

- ↑ Richard Deacon: Kempei Tai. Tokyo: Tuttle, 1983, pp. 156-167

- ↑ https://np.reddit.com/r/news/comments/4g3z4v/alabama_flag_among_state_banners_removed_from_us/d2efmt9

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Operation Trust.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Hundred Flowers Campaign.

- ↑ George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

- ↑ Seth Finkelstein, "Libertarianism Make You Stupid".

- ↑ p. 312 — Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell, Penguin, 1989

- ↑ p. 314 - Nineteen Eighty-Four

- ↑ p. 220-1 - Nineteen Eighty-Four

- ↑ Chapter 3 of Nineteen Eighty-Four on Wikiquote

- ↑ "Memory Hole in 1984" on Study.com

- ↑ James F. McGrath. "Big Brother's Young-Earth Creationism".

- ↑ Was George Orwell just a dirty old man? CRAIG BROWN explains why the novelist would probably have got himself in trouble in the current climate, Craig Brown, The Daily Mail, 15 February 2018.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Was Orwell an anti-Semite?, Ha'aretz, 03.08.2012

- ↑ Orwell's evolving views on Jews, Raymond S. Solomon, The Jerusalem Post, Oct 18, 2019

- ↑ ‘It was always the women’: Misogyny in 1984., Meia, Medium, Sep 22, 2017

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Eric & Us.

- ↑ Such were the joys (review of Eric & Us by Jacintha Buddicom), Kathryn Hughes, The Guardian, Feb 17, 2007

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Orwell's list.

- ↑ Did George Orwell shoot an elephant? His 1936 'confession' – and what it might mean, Gerry Abbott, The Guardian, Mar 18, 2017

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac. Review of 1984, published 1980.

- ↑ Readers may wish to read Orwell's account of his experiences: Homage to Catalonia from 1938.

- ↑ https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/o/orwell/george/o79d/complete.html

- ↑ https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/o/orwell/george/o79b/complete.html

- ↑ https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/o/orwell/george/o79r/complete.html

- ↑ http://www.netcharles.com/orwell/essays/nicecupoftea.htm

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2003/mar/07/artsfeatures.georgeorwell

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0204824/combined

- ↑ Sales of Orwell's '1984' spike after Kellyanne Conway’s 'alternative facts' by Travis M. Andrews (January 25 at 5:52 AM) The Washington Post.

- ↑ The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters by Frances Stonor Saunders (2013) The New Press, 2nd ed. ISBN 1595589147.

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20091016092825/http://1984comic.com/pdf/1984comic_chapter_01.pdf

- ↑ http://web.archive.org/web/20091016092916/http://1984comic.com/pdf/1984comic_chapter_02.pdf