Dictatorship

| Oh no, they're talking about Politics |

| Theory |

| Practice |

| Philosophies |

| Terms |

| As usual |

| Country sections |

|

|

“”If you want to preserve — I'm very serious now — if you want to preserve democracy as we know it, you have to have a free and, many times, adversarial press. And without it, I am afraid that we would lose so much of our individual liberties over time. That's how dictators get started.

|

| —US Senator John McCain (R-Arizona), 19 February 2017.[1] |

“”People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.

|

| —Franklin D. Roosevelt[2] |

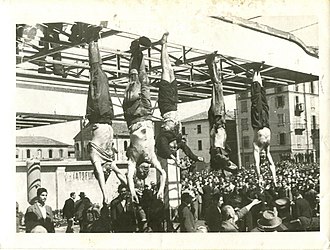

A dictatorship is a regime ruled by one or more authoritarian political leaders with very few (if any) checks on their legal power. These leaders are called dictators, ![]() and the relative lack of restraints placed on their rule tends to enhance their negative personality traits and desire for more power. Thus, the leadership of a dictator tends to begin with or devolve into corruption and brutality. They almost always benefit from the backing of some powerful group of people who benefit personally from their rule, especially if that group is wealthy. Dictators also typically use methods such as intimidation, imprisonment, or violence to silence opposition to their rule. While the pages of modern history are stained by the blood of the victims of dictators like Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Pol Pot, or any other example you care to name, dictatorial government remains the way of life in much of the world. Dictators are usually considered distinct from monarchs, as dictators don't tend to inherit their power by being born at the right time but often have fewer restrictions on their power.[3] Monarchs can be dictators (such as Mohammad bin Salman), or not (such as in the case of constitutional monarchies).

and the relative lack of restraints placed on their rule tends to enhance their negative personality traits and desire for more power. Thus, the leadership of a dictator tends to begin with or devolve into corruption and brutality. They almost always benefit from the backing of some powerful group of people who benefit personally from their rule, especially if that group is wealthy. Dictators also typically use methods such as intimidation, imprisonment, or violence to silence opposition to their rule. While the pages of modern history are stained by the blood of the victims of dictators like Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Pol Pot, or any other example you care to name, dictatorial government remains the way of life in much of the world. Dictators are usually considered distinct from monarchs, as dictators don't tend to inherit their power by being born at the right time but often have fewer restrictions on their power.[3] Monarchs can be dictators (such as Mohammad bin Salman), or not (such as in the case of constitutional monarchies).

In the modern world, especially after World War II, dictatorships and their rulers are typically seen as contrary to established international values. The United Nations, for instance, counts most nations of the world in its membership and recognizes an International Day of Democracy, and sometimes warns against democratic backsliding.[4] In response, most dictators have recognized that the appearance of democratic rule is actually useful to them, as it convinces the populace to view them as legitimate.[5] Tactics for accomplishing the appearance of democracy include holding regular but unfree elections (a current favorite in Russia[6] and Belarus[7]), voicing support for democratic values and human rights in other countries (as China does frequently[8]), or just flatly insisting that they either still are or always have been democratic rulers (as in Uganda[9] or Egypt[10]). The Chinese Communist Party, for its part, claims that its regime is more democratic than the United States.[11]

Dictatorships also often benefit from the support of more powerful nations, including those that consider themselves to be exporters of democracy. As part of the Cold War, the former Soviet Union, itself a highly authoritarian government for most of its history, supported dictators in its satellite states who largely acted as Soviet puppets.[12] The United States also frequently supported dictatorships during the Cold War, such as the junta in Argentina or Augusto Pinochet in Chile.[13] Dictatorial American partners in the 21st century include Islam Karimov in Uzbekistan[14] (who liked to boil people alive[15]), or Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea[16] (who has clung to power for more than 40 years[17]), or Egypt's Abdel Fattah al-Sisi[18] (who came to power in a military coup and loves throwing journalists in prison[19]).

As part of our Wiki's mission, dictators are a subject of great importance. They are the most honest embodiment of authoritarianism, and have pretty much a free gateway into brutally curbstomping the rights of just about anyone, and creating an entire nation of misery. Given that the "End of History" was a severe miscalculation, and democracy can slide backwards into rule by a mad dictator, work must be done to understand how the dictatorship is formed, and fortify democratic values and institutions where necessary with this in mind.

Types of dictatorship[edit]

“”There is something desperately boring about despots and plutocrats. And one of the frustrating consequences of an unequal society is that the rest of us have to care what is going on with them.

|

| —Alexandra Petri[20] |

Not all dictatorships are created equal, and many dictators end up hating each other over ideological or territorial reasons. Really, you can look at modern war and find at least a couple of fun examples of this. Classifying dictatorial regimes will be useful for at least noting some of the major differences between them, but one will run into the problem where some regimes fit multiple categories or don't cleanly go into any category at all.

Military dictatorships[edit]

Nothing like starting off with one of the ol' classics. Modern history is filled with images of tinpot dictators in uniforms saluting during some dumbass military parade. In these regimes, as you have surely guessed, political power is centered on the military while some figure associated with them serves as the figurehead of the regime.[21] In some cases, a group of military officials will hold power; this is known as a junta. These regimes almost always arise when the military overthrows a prior regime.[21]

Since these regimes arise through military coups, it's fairly easy to assess risk factors for such a regime rising to power. Young democratic governments without a means of restraining the ambitions of military leaders are common targets, and nations in geopolitically turbulent parts of the world tend to have militaries influential enough to pose a threat to their government.[22] Democratic governments attempting to reform their national military or restrain the power of its leaders often provoke a coup to prevent that from happening.[22] Economic inequality also increases coup risk, as the military can appear more competent and its wealthy leaders wield outsized economic influence.[22] This is the major reason why the United States has such stringent legal restrictions on its military, with its leadership under the control of civilians and it being expected to be apolitical.[23] The US military, despite being the most powerful in the world, is firmly under control.

Military dictators were also common in post-colonial Latin America, as charismatic military leaders who participated in ousting Spanish rule rose to fill the resulting power vacuum and became the infamous caudillos.[24]

An almost universal characteristic of military dictatorships is their reliance on martial law or a permanent state of national emergency, either of which allow the military to exercise extensive control over civilian life.[21] They use the maintenance of public security as a justification for their actions and their continued rule. Their emphasis on restoring and enforcing political stability is evident in the names these regimes often take, such as the "Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration" in Burkina Faso[25], or the "National Committee for the Salvation of the People" in Mali[26], or the "State Peace and Development Council" of Burma (which did not bring peace).[27]

In Burma, which had a classic military dictatorship during the 1980s, people lived in fear of being snatched off the streets for dissent and had to pay homage to leading generals of the country's junta.[28] During the Cold War, military dictators across South America kidnapped and murdered tens of thousands of people, sometimes by throwing them out of helicopters and planes while still alive.[29][30] Between 1964 and 1985, Brazil's military dictatorship enforced martial law to close state legislatures and inflict torture and murder on hundreds of dissidents.[31]

Personalist dictatorships[edit]

Personalist dictatorships are regimes propped up by a single leader. While this individual almost always has powerful backers, actual political authority is wielded by and bestowed by the dictator alone. This is probably the most well-known form of dictatorship, as the destruction inflicted by personalist dictators can and does fill history books. Ubiquitous in these regimes are cults of personality in which the state makes an effort to enforce an idealized image of the dictator through propaganda and rallies.

Regimes centered on a single individual arise in environments in which institutions are too weak to restrain their ambitions. Unlike a military dictatorship, which arises when political power structures are weak, personalist dictatorships result when the military is also too weak to form institutions around them.[32] These regimes also arise when the backers who sweep the dictator into power become less influential than the dictator or else rely on him to maintain their position.

Due to a complete lack of checks on the dictator's power, personalist regimes are by far the most dangerous. They behave more brutally towards their own people and are more aggressive in foreign policy.[33] They also fall victim to corruption more quickly and completely than other forms of dictatorship, as the leader's autonomy in delegating power allows him to favor loyalty over competence.[34] Having such compliant staffers and bureaucrats also means the dictator will tend to lack accurate intelligence, as these staffers will fear passing on negative news or reporting their own failures.[35] This makes personalist dictators much more reckless and impairs their ability to address crises both systemic and urgent.

The most infamous example of a personalist dictator in recent times is Vladimir Putin of Russia, who tossed a big chunk of the world into chaos by invading Ukraine. While Putin is supported by Russia's wealthy oligarch class who prosper from his rule, these oligarchs have little to no influence on his actual political decisions.[36] Putin's inner circle are loyal to him personally, and other oligarchs have seen their wealth and positions dependent upon Putin's goodwill.[37] Putin not only seized the reigns of Russia's post-Soviet government, but he also outwitted the oligarchs.

Another example was Saddam Hussein of Iraq, who had images of himself placed on posters and statues across the nation[38] and then began the bloody Iran-Iraq War and the Gulf War. Kim Jong Un, who still rules North Korea to this day, is another personalist dictator who benefits from the power structures established by his father and grandfather. Kim likes to demonstrate his authority over the North Korean government by purging officials like the ill-fated defense minister Hyon Yong-chol in 2015 or killing his own family members in the government like his uncle Jang Song-thaek in 2013.[39] Every member of the North Korean government is completely beholden to the whims of Kim.

Certainly the most well-known personalist dictator is Adolf Hitler, who had his face plastered across busts, posters, postcards, matchbooks, playing cards, Christmas decorations, Wehrmacht and Hitler action figures, posters, you name it.[40] While Hitler wielded power through the Nazi Party, he was in no way subordinate to its internal structures, and the major party figures were loyal to him personally. Also, his acts of geopolitical aggression plunged the world into World War II and resulted in Germany getting obliterated.

Xi Jinping, the current president of China, also arguably fits here despite theoretically being the leader of a party-based regime. While he started off as a simple cog in the Chinese Communist Party, he used efficiency-based reforms and anti-corruption purges to stack the party with his loyalists and center its institutions around him.[41] His absolute rule became apparent when he emerged from the 2022 Party Congress having obtained a previously illegal third term in power as well as an amendment to the party constitution describing him as the "core" of the party.[42]

Adolf Hitler addresses the Reichstag, 1939. You can't have a dictator list without this guy.

Benito Mussolini poses for propaganda. The helmet makes him look even goofier.

Saddam Hussein on a throne, 1988. Bonus points for his dictator moustache.

Kim Jong-un having lunch in Pyongyang, 2018. Completely lacks machismo, but makes up for it with brutal reputation.

Xi Jinping addresses Chinese Communist Party leaders, 2022. Manages to look dictator-y even with the civilian suit.

Party dictatorships[edit]

As opposed to a military regime, a party dictatorship (branded by Marxist-Leninists as "dictatorship of the proletariat") exercises power over the nation through a single political party which has either banned other parties from elections, or less-frequently subordinated other parties as showpieces (as in China). These were most common during the latter 20th century due to the dominance of the Soviet Union, which wanted other communist states to follow its model of a government run by a single communist party.[43] Party regimes are the easiest to disguise as being democratic, as the party will typically go through the motions of holding elections and incentivizing people to vote for its members. The Soviet Union, which serves as the primary example of such a government, had no legal opposition to its party but still encouraged people to cast votes and did their best to turn elections into festive occasions.[44] Ballots were thus a simple yes-or-no on the single candidate offered, and blank ballots were counted as approval of the candidate.[44] However, Soviet citizens could express their thoughts by writing messages on the ballots, something the Soviet government kept tabs on.[45]

Party dictatorships are typically more politically stable than other kinds of dictatorships, a fact largely attributable to the veneer of legitimacy offered by the political party and the elections it holds.[46] This also makes party regimes more durable than other kinds of dictatorships, as the power structures will last beyond a single leader's death (a key problem of personalist regimes) and power isn't solely reliant on military force (a key problem of military regimes).

On the much more negative side, a party dictatorship will still typically have the hallmark brutality and poor governance of other forms of autocratic rule. China, the world's current most influential example of a party regime, only has competitive national elections for the National People's Congress which in turn meets only a few times per year to confirm decisions made by unelected Communist Party officials.[47] China's government routinely executes people for drug offenses, censors media and internet (Great Firewall of China), arrests dissidents, and persecutes ethnic minorities (e.g., Uyghur genocide).[48]

Additionally, party regimes frequently find their leaders crossing the line into personalist rule by enforcing cults of leadership and seizing control of party apparatuses. As discussed above, Xi Jinping has already managed this by stacking the party with his loyalists and purging anyone who opposed him.[41] The lack of checks on the party's power now means a lack of checks on Xi's power. Stalin also took control of the Soviet Union's ruling party by having his political opponents arrested and executed, and he went on to perpetrate some of history's most infamous crimes like the Holodomor[49] and Soviet complicity in dividing Europe with Nazi Germany[50] and fueling the German war machine.[51] Having so few barriers between party leaders and absolute rule is yet another critical flaw of a one-party dictatorship.

Vladimir Lenin giving a speech in the Red Square, 1919. His dictator posing game is on point.

Erich Honecker inspects troops in East Germany, 1976. A classic dictator pastime.

Raúl Castro in Mexico, 2015. Looks more abuelo than autocrat.

Thongloun Sisoulith, current leader of Laos. Also lacks machismo.

Vietnamese leader Nguyễn Phú Trọng meets Donald Trump, 2019. But look! Hồ Chí Minh wants to be in the picture too!

Absolute monarchies[edit]

This is where the line between dictatorship and monarchy starts to blur. However, some points must be made. Firstly, many of history's monarchies were not absolute in the way we might consider today. Medieval monarchies, for instance, were quite decentralized under the system of feudalism, where regional nobility had significant authority over their own lands and people.[52] Even the monarchs of the 17th century "Age of Absolutism" struggled to exercise their power without limitations. Louis XIV of France, the quintessential absolute monarch of the era, had to deal with local nobles and the fact that towns and provinces had their own privileges and systems of law.[53] As American Renaissance historian William Bouwsma said, "Nothing so clearly indicates the limits of royal power as the fact that governments were perennially in financial trouble, unable to tap the wealth of those most able to pay, and likely to stir up a costly revolt whenever they attempted to develop an adequate income."[54] The fact is, most pre-modern monarchies, being based on traditional rights and privileges, effectively limited monarchial power through extra-legal means. A monarch could only break with tradition to bolster their own power so much before the nobility started pushing back.

After World War I, the world generally trended away from powerful monarchies even further. However, absolute monarchies still exist, and with the advantages of modern communications and theories of governance they are arguably more absolute than ever before. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, all high-level government posts are appointed by the monarch and tend to be filled with members of the royal family.[55][56] Even here, the king must comply with certain restrictions. His decrees must be in accordance with Islamic law, and his government tends to consult with tribal leaders and important commercial families on major decisions to avoid alienating them.[55] Bahrain, a fellow absolute monarchy, is slightly better in that it at least has an elected parliament, but candidates are vetted for loyalty to the crown and elected members are excluded from decision-making by the king's appointed cabinet members.[57]

A particularly interesting example of a monarch as a dictator is Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, who took his throne through a coup rather than succession. Napoleon was a true absolutist in that he made political decisions without consulting anyone else either noble or otherwise, and he was not bound by traditions due to having come to power in a time of upheaval.[58] He also dodged the problems Louis XIV faced by forcibly standardizing French law with his Napoleonic Code in 1804.[59]

Theocratic dictatorships[edit]

In a theocratic regime, God or whoever the government worships is theoretically in charge. In reality, God doesn't seem too keen on the day-to-day business of running a government (God also really likes taking Sundays off) so the real decisions are made by men who claim to speak for him. These men, you guessed it, typically have few limitations on their power and thus rule as dictators. These rulers are also unusually self-righteous and willing and eager to pry into people's personal lives. This kind of dictatorship is easily the rarest today, although that's little consolation for the unfortunate souls who live under them.

The obvious case example to study such a regime in the modern day is Iran, which is ruled by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei along with some who-gives-a-fuck president. The Supreme Leader is head of state, commander-in-chief of Iran's military, and has personal control over the criminal and morality police.[60] While Iran's president is directly elected, he holds relatively little authority,[60] and election candidates are vetted and subject to disqualification by the religious "Guardian Council" who are appointed by the Supreme Leader.[61]

Iran's morality police enforce a totalitarian dress code on Iran's women, using violent harassment and forced reeducation to bring the noncompliant back into line.[62] In 2022, national protests erupted after the morality police allegedly beat 22 year-old Mahsa Amini to death for having some hair showing from under her hijab.[63] The paramilitary group Basij Resistance Force also enforced morality standards by monitoring the activities of citizens, confiscating any material they consider "obscene", breaking up any female-male fraternization, and beating up critics of the government.[64]

The Taliban in Afghanistan was (and sadly now is) also an especially brutal form of theocratic government. In the old pre-2001 regime, men were forbidden from shaving their beards, women had to cover themselves from head-to-toe, and attending daily prayers was mandatory.[65] The Taliban is currently led by the Rahbari Shura, a leadership council chaired by the reclusive Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada.[66] Other members of the Taliban regime are terrorists wanted by the US and sanctioned by the UN.

Weaknesses of dictatorship[edit]

“”And so we think, but we don’t know, that he [Putin] is not getting the full gamut of information. He’s getting what he wants to hear. In any case, he believes that he’s superior and smarter. This is the problem of despotism. It’s why despotism, or even just authoritarianism, is all-powerful and brittle at the same time. Despotism creates the circumstances of its own undermining. The information gets worse. The sycophants get greater in number. The corrective mechanisms become fewer. And the mistakes become much more consequential.

|

| —Stephen Kotkin[67] |

“”The limits of tyrants are proscribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.

|

| —Frederick Douglass[68]:22 |

While many people in democracies begrudgingly (or enthusiastically) seem to tolerate dictatorship because it seems to "work" better in times of emergency, dictatorships have numerous problems associated with them.

Dictators make dipshit decisions[edit]

Time and time again, people fall into the trap of believing the "savvy evil genius" trope when it comes to the world's vicious dictators when the opposite is actually far more accurate. While dictators don't have to listen to polls or misguided public opinion, they do almost universally surround themselves with yes-men who give them flawed information for the sake of maintaining the dictator's goodwill.[69] Brian Klaas, a politics professor at University College London uses the term "dictator trap" to refer to this phenomenon, which he describes as the consequence of a dictator "starting to believe in the fake realities they’ve constructed around themselves".[70] Another contributing factor to the "dictator trap" is general repression of public discourse and the media, as less criticism of the government leads its members to decide against all evidence to the contrary that things are going fine.

As a result of this, history is filled with examples of dictators making idiot blunders. Mussolini, for instance, declared war on Greece without allowing his generals to draw up a proper invasion plan or gather troops and supplies.[71] He was more concerned with making impressive headlines than he was in waging a competent campaign. As a result, the Greek campaign turned against the Italians and resulted in the Axis' biggest embarrassment during the early phases of World War II.[72]

Vladimir Putin also huffed his own supply leading to his decision to invade Ukraine in 2022. Putin believed that Russia could conquer Ukraine with only 150,000 military personnel and expected Ukraine's political leaders to flee rather than put up a fight.[73] This bad information, apparently fed to Putin by sycophantic advisors, led to the Russian military taking heavy avoidable casualties at the outset of the war and performing abysmally thereafter.

Dictators make incompetent governments[edit]

“”I don't think that Putin is that strong because I've seen it all around Russia. His power, his government is quite ineffective. They are highly corrupted, and they cannot solve the easiest questions. I know regions where schools are left without electricity for weeks, and Putin's government cannot do anything with that.

|

| —Nadya Tolokonnikova[74] |

Dictators are almost always keenly aware of the threat an internal coup poses to their power. They're right, too. Of the autocrats who lost power between 1946 and 2008, 68% were removed by a coup orchestrated by the political elite or with their support.[75] Since they mistrust their own government, dictators attempt to weaken the threat it poses to their power. The result is authoritarian governments tending to be filled with corrupt idiots who could barely be trusted to run a bath, never mind a region or government agency, and True Believers who prioritize ideology even over dealing with existential threats.

Omar al-Bashir of Sudan, for instance, spent 25% of his country's budget on internal security and then turned around and fragmented that security apparatus by encouraging departments to compete against each other with overlapping areas of responsibility.[75] Bashir also weakened his country's military by replacing meritocratic promotions with patrimonial norms of loyalty.[75] All of this ended up being for naught. The Sudanese government became so weak and dysfunctional that the security apparatuses united amid a failing economy in 2019 and dumped Bashir's ass out of power.[75] In trying to defend against a coup, Bashir destroyed his own government and turned the people and the elites against him.

Even China has fallen into this problem. Since coming to power in 2012, Xi Jinping ordered the arrest of 170 ministers and deputy minister-level officials on charges of corruption or violating party discipline, and an estimated 1.34 million lower-level officials have been punished as well.[76] Xi has also sacked more than 60 Chinese generals, and in 2015 he had the third-most powerful man in China (security chief Zhou Yongkang) jailed for life.[76] While it remains to be seen what kind of impact this will have on the Chinese government long-term (and it must be admitted there certainly was a lot of dead weight that needed to be trimmed), there are some serious warning signs that emerged after Xi solidified his dictatorial control in 2022. Senior Chinese Communist Party officials are now almost entirely Xi's yes-men, creating the exact kind of information bubble that leads dictators to bad decision-making, and Xi has also completely erased female representation in the Politburo.[77] Xi has also clamped down on anyone competent enough to be seen as a potential successor, and he has determinedly excluded younger officials from leadership.[77] This puts China on the path towards gerontocracy and makes a post-Xi succession crisis likely.

Dictators can cause succession crises[edit]

Speaking of China's potential succession crisis, this is another broader issue with many dictatorial regimes. While democracies typically have stable transitions of power (unless someone like Donald Trump happens), dictatorial succession is frequently the cause of bloody infighting or even outright governmental collapse. A dictator's love for power is only matched by their reluctance to consider their own mortality. The yes-men who surround the dictator certainly won't bring up the topic either, and the national media will be forced into silence on the matter. Therefore, dictatorships are almost always caught by surprise in the event their leader decides to leave office through the trapdoor to Hell.

Putin, for instance, despite being no spring chicken (he was born in 1952), refuses to consider what will happen after his death and maintains that discussing this topic "destabilizes" Russia.[78] Part of his rationale for avoiding the topic of succession must also be to avoid emboldening the ambitious. His regime featured rising stars like Chechen lunkhead Ramzan Kadyrov and paramilitary thug (and former hot dog vendor) Yevgeny Prigozhin, both of whom made waves during the Ukrainian war by criticizing generals and government officials.[79] Prigozhin is dead now after attempting a coup against Russia's military establishment.[80] It is unclear what will happen when Putin dies, but internal back-stabbing/door-handle-poisoning is quite probable.

In Spain, a succession crisis ensued after the famously lingering death of Francisco Franco. Franco's hastily-chosen successor, Prince Juan Carlos I, took the Spanish throne shortly after Franco's death in 1975 and promptly betrayed the dead dictator's memory by beginning the Spanish transition to democracy.[81] Even this resulted in violence, though, as paramilitaries stormed the Spanish parliament and took it hostage for 18 hours in 1981 before surrendering.[82]

This also reveals an obvious problem with any theories of so-called "benevolent" dictatorship. Even if you could find a dictator who was competent and morally upstanding, unless that dictator happens to be immortal that still leaves the problem of their successor. The brutal but well-meaning Vladimir Lenin famously wrote on his deathbed that Joseph Stalin would be a poor leader for the Soviet Union, and Stalin's actions vindicated him in the worst possible way.[83]

Dictators are bad at war[edit]

“”We are at war and the decision of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief in such a situation cannot be challenged.

|

| —Pro-Kremlin journalist Andrey Medvedev accidentally explains why Russia did so poorly while invading Ukraine, 10 November 2022.[84] |

Strength has always been one of the selling points of dictatorship. However, when push comes to shove, they typically underperform when it comes to using that strength on the battlefield. This is yet another symptom of dictators centralizing power around themselves and becoming isolated in a bubble of bad information. A leader trying to manage everything themselves while relying on faulty information from their lackeys is gonna fuck up a campaign a lot more than one who delegates properly. From 1921 to 2007, personalist dictators initiated far more conflicts than any other type of leader and lost 73% of the times they did so.[85]

This is already obvious when looking at recent history. Putin's decision to invade Ukraine was a shitty move on its own, but he also botched it by focusing on shiny military toys and grand maneuvers than the boring work of logistics (e.g., feeding the troops decent food).[85] Another source of failure was Putin's habit of using the military to hide his own corruption by funneling money to his own and his pals' bank accounts rather than weapons and training for Russian soldiers.[86]

Failing at warfare despite aggression is another common thread to be found when looking at history's dictatorships. Adolf Hitler, for instance, wielded personal control over much of Germany's war effort during the Second World War and made critical blunders like betting everything on Stalingrad and then betting everything on Kursk and then betting everything on the 1944 Ardennes offensive,[87] and you see where we're going here (The Bunker Scene[88]). From the same time period comes the Red Army's abysmal performance during the opening stages of the German invasion, driven by Stalin's decisions to execute the Soviet Union's best military theorist (Marshal Tukachevsky) and purge some 30,000 officers from the military.[89]

Dictators like to steal from the cookie jar[edit]

“”[...]the entirety of Mobutu's reign was absolutely littered with corruption and embezzlement. It started off small and got worse and worse over the years. Mobutu himself was pretty open about it, once saying, "If you want to steal, steal a little in a nice way. But if you steal too much to become rich overnight, you will be caught." Very wise advice from the leader of a country. His strategy was essentially to skim a little off the top of the government's funds, slowly embezzling it to make himself rich. But even he failed to take his own advice, stealing more and more as he continued to get away with it. In 1970, it was estimated that he had stolen 60% of the nation's budget that year, and it only got worse.

|

| —A Grain of Salt, on Congolese/Zaïrean dictator Mobutu Sese Seko[90] |

While democratic governments have corruption problems, political corruption is a much greater feature of autocratic regimes. Taking state funds is a nearly irresistible temptation for someone with absolute power, and funneling money into the pockets of elites is a surefire way to make sure they continue to back the leader even when things start going wrong.[91] Corruption is also useful to the dictator just for existing. If public support seems to be lagging, a nice anti-corruption campaign to punish the most inconvenient offenders can make positive headlines and win it back (even if nothing changes).[92]

Some dictators rank among the worst thieves in history. For instance, Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines bought his wife 3,000 shoes with state money, Mobutu Sese Seko stole $12 billion in foreign aid from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Suharto stole as much as $35 billion from Indonesia during his time in power.[93] In the destitute nation of Haiti, dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier stole at least $120 million from the government, which is a lot of fucking money to take from the coffers of the Western hemisphere's poorest country, only to pay the Paris-centered hexagon even more.[94] Amid critical shortages of food and medicine in Venezuela, authoritarian president Nicolas Maduro awarded government contracts to his cronies to pocket the cash and redirected food away from regions that opposed him.[95]

And stealing money from their nation really is a case of dictators screwing themselves in the long-term. Not only does it piss off the population, but it stunts the growth of their national economies and therefore hurts everyone.[91] In the long-term they'd be even richer if they let a portion of that capital escape to their subjects. Though there is reason to doubt the money would ever get to the bottom: corruption at the top tends to percolate downward as underlings at each level need to pay 'gifts' to their superiors to maintain their positions. In Suharto's Indonesia, corruption affected every level of government down to the school teachers.[96]:26

Dictators are bad for the economy[edit]

| —Moses Chikomba, interview in The Times (quoted in The New York Times) about Zimbabwe's severe hyperinflation[97] |

When researchers from RMIT University and Victoria University in Australia analyzed the relationship between economic growth and national leadership between 1858 and 2010, they found that countries under dictatorial rule experienced economic growth very rarely.[98][99] This study was in response to the worldwide trend of populations looking for a strong leader to help them out of economic trouble. The truth is, dictators are even worse.

Probably the most infamous example of a dictator mismanaging the economy is Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, who managed to dump his country into the toilet during his years in power. Mugabe first did the classic move of paying off his political supporters, but he did so by printing cash and thus crashing the value of his currency by 72%.[100] He then sent troops into the (non-adjacent) Democratic Republic of the Congo to intervene in their civil war, a move which came with a price tag of $1 million per day.[101] Then he paid off his cronies again by confiscating farmland from white farmers and handing the land out to kleptocrats who had no interest in agriculture.[102] This tanked food production. And then on top of that Mugabe decided to have his thugs bulldoze tens of thousands of homes across the country in retaliation for poor people voting against him.[103] The end result was one of the worst economic crises in known history. In 2009, hyperinflation became so absurd that Zimbabwe had to issue a $100 trillion note worth about $30 US.[104] In terms of percentages, inflation hit 59% in 2000, inflation then ran at almost 600% by 2003 and, in 2006, it hit the scarcely-believable rate of 1,200%.[105] The following year it hit a rate of 66,200%, and by the end of 2008, it had hit nearly 80,000,000,000% (80 billion percent).[105] What the fuck?! Mugabe's response to this, by the way, was banning inflation, a move which worked as well as you think it did.[105]

Sometimes dictators go batshit crazy[edit]

In the worst case scenario, a dictator will come to power and then go off the deep end. With no checks on their power and influential supporters growing rich from their rule, there really is no immediate way to put a stop to them.

A relatively harmless example is Saparmurat Niyazov of Turkmenistan, who declared himself "President for Life"[106] and then used that power to rename the months of the year after himself and his family members[107] and had the state build a giant tripod topped with a 39ft (12m) golden statue of himself that would always rotate to face the Sun.[108] To top it off, he had poor neighborhoods bulldozed to make way for a Niyazov-themed amusement park called the "Land of Fairy Tales".[109] The sheer audacious hilarity of Niyazov's antics obscure the human cost of his rule. During his time in power, the Turkmen people had to endure famines, arbitrary arrests, torture, and the random bulldozing of entire neighborhoods to make way for vanity projects.[110]

Idi Amin of Uganda was much worse. He ordered underground dungeons to be built under Uganda's cities where his political opponents would be ruthlessly tortured.[111] His taste for murder began when he had death squads massacre some 6,000 soldiers loyal to Uganda's old president and continued to have tens of thousands more people tortured to death in increasingly sadistic ways such as drowning or being fed to crocodiles.[112] He allegedly once had so many corpses dumped in the Nile that the remains clogged the intakes of Uganda's main hydroelectric plant.[113] In 1976, Amin claimed to have tasted human meat, describing it as more salty than he had expected.[112] In 1978, he ordered the invasion of Tanzania on a whim, despite Tanzania being much larger than Uganda.[112] The war unsurprisingly went poorly for him and resulted in his downfall.

And then, there is Adolf Hitler who used his unlimited power to try to kill all of the Jews, and he came close to succeeding, only to be stopped by the Allies in WW2.

Even dictators who fall short of complete insanity can humor some strange obsessions. François Duvalier of Haiti associated himself with voodoo imagery in an attempt to terrify people, and he claimed to have put a death curse on John F. Kennedy.[114] Romanian communist leader Nicolae Ceaușescu was obsessed with boosting birthrates; he banned all abortions, punished childless couples, and mandated that women undergo monthly gynecological exams.[115] Libyan dictator Muammar al-Gaddafi had a fantastically creepy crush on former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and rebels found a photo album of Rice in the dictator's compound after his 2011 downfall.[116]

Followers and enablers[edit]

“”A dictator is generally a man who, starting from the bottom, throws himself into an even deeper hole. A curious phenomenon then occurs: everyone looks at him… and jumps into the void after him.

| ||

| —Charlie Chaplin[117]:16-17 |

The dictator is no one without his supporters, the immediate coterie who benefit directly from the largesse of corruption, the cheering crowds who are captivated by the perceived charisma and who may benefit from the privilege bestowed upon their social class, gender or race.[118]:13-14 Foreign financial enablers (Deutsche Bank, Swiss banks and other countries with bank secrecy) have benefited directly by making loans to corrupt states or authoritarians and hiding dictators' assets.[118]:14

Resisting looming tyranny[edit]

“”The tyrant will always find a pretext for his tyranny, and it is useless for the innocent to try by reasoning to get justice, when the oppressor intends to be unjust.

|

| —Aesop[119] |

Timothy Snyder,![]() a Yale University history professor and expert on Hitler, Stalin, and the Holocaust wrote a small book, On Tyranny, on ways to recognize and resist impending tyranny. He gives twenty lessons from history on ways that tyrants can take over a country:[120]

a Yale University history professor and expert on Hitler, Stalin, and the Holocaust wrote a small book, On Tyranny, on ways to recognize and resist impending tyranny. He gives twenty lessons from history on ways that tyrants can take over a country:[120]

- "Do not obey in advance": "Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. … A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do."

- "Defend institutions": Institutions help to preserve decency but institutions do not protect themselves.

- "Beware of the one-party state": Support multi-party systems, vote in local and state elections while you can, run for office. Each election in an authoritarian government could be the last real one in your lifetime (Germany 1932, Czechoslovakia 1946, Russia 1990, Belarus 1994)

- "Take responsibility for the face of the world": Remove signs of hate where you see them in the real world.

- Remember professional ethics: When you maintain professional ethics, you support the rule of law (particularly if you work in law or the government).

- "Be wary of paramilitaries": Paramilitaries have been used as an important tool by dictators to solidify power (e.g. the SA and SS in Nazi Germany). Militias, private security (e.g., Blackwater), and private prisons are similarly organizations to be wary of.

- "Be reflective if you must be armed": In both the Holocaust and the Stalin's Great Terror (Great Purge

), police played key roles in perpetuating atrocities.

), police played key roles in perpetuating atrocities. - "Stand out": Do not concede to tyranny in advance. Stand out, as Churchill against the might of Nazi Germany, as Rosa Parks

did against Jim Crow laws, and as other lesser-known people have done.

did against Jim Crow laws, and as other lesser-known people have done. - "Be kind to our language": autocrats often attempt to pervert the meaning of words for their own ends (e.g., Hitler's 'the people' used to exclude most people, Trump's use of 'libel' to mean anything negative that is said about himself). Falling into the autocrat's linguistic trap should be resisted. Two useful books detail this behavior: Fahrenheit 451 and 1984, and Snyder lists several other books that are worth reading for understanding the rise of authoritarianism.

- "Believe in truth": "To abandon truth is to abandon freedom." Snyder cites Victor Klemperer

on the four modes in which truth dies:

on the four modes in which truth dies:

- Open hostility to verifiable reality (e.g., 78% of Trump's factual claims were false during his 2016 campaign)

- 'Shamanistic repetition' (a.k.a., the big lie)

- 'Magical thinking', meaning the open embracing of contradiction, not the usual meaning (magical thinking)

- Misplaced faith: believing in the leader above all else, and self-deification of the leader (e.g., the Religious Right's embrace of Trump, or Trump's "I alone can solve it."[121])

- "Post-truth is pre-fascism."

- "Investigate": "Figure things out for yourself. Spend more time with long articles. Subsidize investigative journalism by subscribing to print media. Realize that some of what is on the internet is there to harm you." This is not the same as 'Do your own research.'

- "Make eye contact and small talk": "This is not just polite. It is part of being a citizen and a responsible member of society. … If we enter a culture of denunciations, you will want to know the psychological landscape of your daily life."

- "Practice corporal politics": "Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them."

- "Establish a private life": "Nastier rulers will use what they know about you to push you around. Scrub your computer of malware on a regular basis. Remember that email is skywriting."

- "Contribute to good causes": Be active in organizations, political or not, that express your own view of life. Pick a charity or two and set up autopay." This supports civil society and others to do good.

- "Learn from peers in other countries": "Keep up your friendships abroad, or make new friends in other countries. The present difficulties in the United States are an element of a larger trend. And no country is going to find a solution by itself. Make sure you and your family have passports."

- "Listen for dangerous words": "Be alert to the use of the words 'extremism' and 'terrorism'. Be alive to the fatal notions of emergency and exception. Be angry about the treacherous use of patriotic vocabulary."

- "Be calm when the unthinkable arrives": "Modern tyranny is terror management. When the terrorist attack comes, remember that authoritarians exploit such events in order to consolidate power."

- "Be a patriot": "Set a good example of what America means for the generations to come. They will need it." This chapter is in part a scathing attack on a nameless coward: "What is patriotism? Let us begin with what patriotism is not. It is not patriotic to dodge the draft and to mock war heroes and their families. …"

- "Be as courageous as you can": "If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die under tyranny." This chapter offers two brief critiques:

- Of the politics of inevitability (teleology), the idea that the past and present determines the (usually positivist) future, and

- Of the politics of eternity (good old days), that the past was better (as viewed through a fogged history of national victimhood).

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Video of Despotism, made in 1946 by Encyclopaedia Britannica Films

- How to Become a Dictator, WikiHow (Wayback Machine)

- History Professor Answers Dictator Questions by WIRED

References[edit]

- ↑ McCain Defends a Free Press: ‘That’s How Dictators Get Started’. CNBC.

- ↑ The Economic Bill of Rights by Franklin D. Roosevelt (January 11, 1944) UShistory.org.

- ↑ Democracy, Monarchy And Dictatorship: Types Of Government Systems. Borgen Project.

- ↑ UN chief raises alarm over ‘backsliding’ of democracy worldwide. United Nations News.

- ↑ Why Do Dictators like to Appear Democratic? El Pais.

- ↑ Why we must not recognize Russia’s fraudulent election. Atlantic Council.

- ↑ Putin’s ally stole my democratic victory in Belarus. Now the west must help us fight back. Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. The Guardian.

- ↑ Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying's Regular Press Conference on April 7, 2017.

- ↑ I don’t need lectures about democracy -Museveni. The Independent Uganda.

- ↑ Sisi Can't Disguise Egypt's Dictatorship as a 'New Republic'. Dawn: Democracy for the Arab World Now.

- ↑ China claims to have ‘democracy that works’ ahead of Biden summit. Al Jazeera.

- ↑ USSR satellites. The National Archives.

- ↑ 35 countries where the U.S. has supported fascists, drug lords and terrorists. Salon.

- ↑ U.S. Hopes to Build on Cooperation With Uzbekistan. US Department of Defense.

- ↑ Uzbekistan: So Now Prisoners are Frozen Instead of Boiled? EurasiaNet.

- ↑ Equatorial Guinea Is Everything Wrong With U.S. Foreign Policy. Foreign Policy.

- ↑ 5 surprising facts about Equatorial Guinea. Deutsche Welle.

- ↑ Al-Sisi’s Western Benefactors Are Betraying Egypt’s Democratic Struggle. Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ Five Years after Sisi’s Coup: Soul Searching, Resistance, and Division. Arab Center Washington DC.

- ↑ Not another column about Elon Musk by Alexandra Petri (December 17, 2022 at 8:35 a.m. EST) The Washington Post.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 What Is a Military Dictatorship? Definition and Examples. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 A Theory of Military Dictatorships. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- ↑ An apolitical military is essential to maintaining balance among American institutions. Military Times.

- ↑ 19th Century Caudillos. Oxford Bibliographies.

- ↑ Burkina junta says country will return to constitutional rule only when "strong". Africa News.

- ↑ Mali: Transition Authorities Should Promote Justice. Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ Bipartisan Bill Helping Political Prisoners In Burma. Borgen Project.

- ↑ Myanmar: What was it like growing up under military rule? BBC News.

- ↑ Chile The Center for Justice and Accountability.

- ↑ Argentina's Last Dictator Sentenced To 20 Years In Prison For Cross-Border Conspiracy. NPR.

- ↑ No Justice for Horrors of Brazil’s Military Dictatorship 50 Years On. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ Putin’s War and Personalist Authoritarianism. Niskanen Center.

- ↑ Frantz, Erica; Kendall-Taylor, Andrea; Wright, Joseph; Xu, Xu (27 August 2019). "Personalization of Power and Repression in Dictatorships". The Journal of Politics. 82: 372–377. doi:10.1086/706049. ISSN 0022-3816. S2CID 203199813.

- ↑ Ezrow, Natasha M.; Frantz, Erica (2011). Dictators and Dictatorships: Understanding Authoritarian Regimes and Their Leaders. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781441196828. p. 134–135.

- ↑ Why the best way to stop strongmen like Putin is to prevent their rise in the first place. The Conversation.

- ↑ Russian oligarchs don’t have the power — or inclination — to stop Putin. Washington Post.

- ↑ Can Russian oligarchs influence Putin’s war? Vox.

- ↑ Iraq's Cult of Saddam Creates A Perfect Picture of Oppression. Christian Science Monitor.

- ↑ North Korea’s Power Structure. Council on Foreign Relations.

- ↑ Exhibit of Nazi memorabilia explores Hitler personality cult. France24.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 How Xi Jinping made himself unchallengeable. BBC News.

- ↑ China's Xi Jinping emerges from the Communist Party congress with dominance. NPR.

- ↑ Magaloni, Beatriz; Kricheli, Ruth (2010). "Political Order and One-Party Rule". Annual Review of Political Science. 13: 123–143. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220529.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Were there any elections in the USSR? Russia Beyond.

- ↑ Elections: A Feedback Mechanism in the Soviet Union? Wilson Center.

- ↑ Aksoy, Deniz; Carter, David B.; Wright, Joseph (1 July 2012). "Terrorism In Dictatorships". The Journal of Politics. 74 (3): 810–826. doi:10.1017/S0022381612000400. ISSN 0022-3816. S2CID 153412217.

- ↑ China 2022. Freedom House.

- ↑ China 2021. Amnesty International.

- ↑ Cut off from food, Ukrainians recall famine under Stalin, which killed 4 million of them. Washington Post.

- ↑ German-Soviet Pact. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ↑ The Chargé in the Soviet Union (Thurston) to the Secretary of State. US State Department Office of the Historian.

- ↑ The Fall of Rome and its Effects on Post-Roman and Medieval Europe. Medium.

- ↑ Absolutism. Louix XIV.

- ↑ Bouwsma, William J., in Kimmel, Michael S. Absolutism and Its Discontents: State and Society in Seventeenth-Century France and England. Transaction Books, 1988. ISBN 0887381804.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Saudi Arabia. Lumen Learning.

- ↑ Saudi Arabia 2022. Freedom House.

- ↑ Bahrain 2022. Freedom House.

- ↑ The Empire. Dictatorship? Monarchy? Foundation Napoleon.

- ↑ The Code Napoleon. Constitutional Rights Foundation.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Who is in charge of Iran? BBC News.

- ↑ Access Denied: Iran’s Exclusionary Elections. Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ Iran’s morality police have terrorized women for decades. Who are they? CNN.

- ↑ Iran protests: Mahsa Amini's death puts morality police under spotlight. BBC News.

- ↑ Iran's Basij Force — The Mainstay Of Domestic Security Radio Free Europe.

- ↑ Matinuddin, Kamal (1999). "The Taliban's Religious Attitude". The Taliban Phenomenon: Afghanistan 1994–1997. Karachi: Oxford University Press. pp. 34–43. ISBN 0-19-579274-2. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ↑ The Taliban in Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Relations.

- ↑ The Weakness of the Despot: An expert on Stalin discusses Putin, Russia, and the West. Interview by David Remnick (March 11, 2022) The New Yorker.

- ↑ Two Speeches, by Frederick Douglass: One on West India Emancipation, Delivered at Canandaigua, Aug. 4th: and the other on the Dred Scott Decision, Delivered in New York, on the Occasion of the Anniversary of the American Abolition Society, May, 1857 by Frederick Douglass (1857) C. P. Dewey.

- ↑ Vladimir Putin Has Fallen Into the Dictator Trap. The Atlantic.

- ↑ How Putin became the victim of his own lies. Vox.

- ↑ Greek Tragedy: Mussolini's Disastrous Campaign in Greece. History Net.

- ↑ A Slippery Road: Mussolini’s Disastrous Invasion of Greece. War History Online.

- ↑ Lessons for the West: Russia’s military failures in Ukraine. European Council on Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ Pussy Riot's Nadya Tolokonnikova: Authoritarianism is spreading like 'sexually transmitted diseases', CNN, 18 August 2017, retrieved 15 May 2024

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Sudan’s Uprising: The Fall of a Dictator. Journal of Democracy.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Charting China's 'great purge' under Xi. BBC News.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Xi Jinping chooses ‘yes’ men over economic growth in politburo purge. The Guardian.

- ↑ Putin Says Talk of Succession 'Destabilizes' Russia. The Moscow Times.

- ↑ Putin’s endgame? Kremlin infighting spills into the open. Politico.

- ↑ Yevgeny Prigozhin: A death that will leave a lasting mark on Russian army and elite. The Guardian.

- ↑ Spain's ex-King Juan Carlos: From hero of democracy to tainted exile. Euro News.

- ↑ Civil guards seize Spain's parliament in attempted coup – archive, 1981. The Guardian.

- ↑ Lenin's Testament 1922.

- ↑ Putin supporters left reeling by yet another Russian ‘surrender’ in Ukraine. CNBC.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Why Putin is Losing – The Weakness of Personalist Dictatorship. Jens Koning. Peace Research Institute Oslo.

- ↑ Ukraine fighting Russian Goliath: Why dictators are so bad at war. The Hill.

- ↑ Hitler's Greatest Blunders. History Net.

- ↑ Downfall: Famous Bunker Scene (Dec 1, 2008) YouTube.

- ↑ Rethinking Stalin’s Purge of the Red Army, 1937-38. University Press of Kansas Blog.

- ↑ A Grain of Salt, The Greediest Dictator in Modern History

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Keeping it Family : How Africa’s Corrupt Leaders Stay in Power. Global Geneva.

- ↑ How authoritarian leaders maintain support. MIT News.

- ↑ Suharto, Marcos and Mobutu head corruption table with $50bn scams. The Guardian.

- ↑ Justice Minister Says Duvalier Stole At Least $120 Million. Associated Press.

- ↑ Venezuela crisis: Vast corruption network in food programme, US says. BBC News.

- ↑ Indonesia Handbook by Bill Dalton (1991) Moon Publications. ISBN 0918373727.

- ↑ Zimbabwe Confident After Losing Cash Machine, Mike Nizza, The New York Times, July 3 2008, retrieved May 14 2024

- ↑ Bad for business: Dictators rarely associated with strong economies, study finds. Study Finds.

- ↑ 150 years of data proves it: Strongmen are bad for the economy. Quartz.

- ↑ Robert Mugabe leaves a legacy of economic mismanagement. Al Jazeera.

- ↑ Meredith, Martin (2002). Our Votes, Our Guns: Robert Mugabe and the Tragedy of Zimbabwe. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-186-5. p. 148

- ↑ Dowden, Richard (2010). Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles. London: Portobello Books. pp. 144–151. ISBN 978-1-58648-753-9.

- ↑ The Implementation of Operation Murambatsvina (Clear the Filth). Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ Zimbabwe rolls out Z$100tr note. BBC News.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 How Zimbabwe's economy has collapsed under Mugabe. Sky News.

- ↑ Turkmenistan: Niyazov Named President For Life. Radio Free Europe.

- ↑ Turkmenistan to drop late dictator's month names. The Guardian.

- ↑ Arch of Neutrality. Atlas Obscura.

- ↑ Turkmenbashi's Land of Fairy Tales. Atlas Obscura.

- ↑ Turkmenistan Seen to Be Suffering. The Oklahoman.

- ↑ Ghost Stories: Idi Amin’s torture chambers. International Women's Media Foundation.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 112.2 Why Idi Amin Dada, ‘The Butcher Of Uganda,’ Should Be Remembered With History’s Worst Despots. All That's Interesting.

- ↑ Idi Amin Dead. CBS News.

- ↑ Papa Doc Duvalier: The Voodoo President who killed Kennedy.

- ↑ Romania: Demographic Policy. Country Studies.

- ↑ Photos Reveal Qaddafi’s Diplo-Crush on Rice. New York Times.

- ↑ La Moustache d'Adolf Hitler by Alain Jaubert (2016) Gallimard. ISBN 2070197344.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present by Ruth Ben-Ghiat (2021) W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393868419.

- ↑ Aesop's Fables (1884): 5. The Wolf and the Lamb. Aesopica.

- ↑ On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Timothy Snyder (2017) Tim Duggan Books. ISBN 0804190119.

- ↑ Donald Trump has always expressed love for authoritarian leaders, but we failed to listen: How did the US end up with a president who hates the press and envies dictators like Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin? by Kirsten Powers (June 20, 2018) USA Today.