Socialism

| The dismal science Economics |

| Economic systems |

| Major concepts |

| The worldly philosophers |

“”Socialism is a scare word they have hurled at every advance the people have made in the last 20 years. Socialism is what they called public power. Socialism is what they called social security. Socialism is what they called farm price supports. Socialism is what they called bank deposit insurance. Socialism is what they called the growth of free and independent labor organizations. Socialism is their name for almost anything that helps all the people.

|

| —Harry S. Truman[1] |

Socialism is a wide movement proposing a fairly broad set of related socio-economic systems, aiming to create a more egalitarian society where the bulk of the means of production are owned by the workers or the community at large (typically through state ownership as an intermediary).[2][3][4][5] Alternatively, for most conservatives and libertarians, socialism is widely regarded as "when the gummint does stuff".[6]

Socialists are also commonly defined as those who wish to abolish private property, which has led to opponents claiming "socialists are coming for your toothbrush!" and the like. However, this comes from a misunderstanding of what most socialists mean by "private property". For them, it relates to the dynamic between the owner and the actual user of the property, such as the one a business owner and their employee have in an average capitalist firm. In this context, the former is able to profit despite not actually needing to do the work themselves. Socialists consider this exploitative, as it deprives the employee of the "fruits of their labor" for an individual's self-gain. They contrast this kind of property with one's actual possessions, often called "personal property".[7][8][9][10]

People who believe in socialism are referred to variously as "socialists" or "communists" — the technical difference being that communists see socialism as a "transitory phase" towards a communist society,[11] while socialists may not, meaning not every socialist is a communist. One of the main distinctions between a communist and a socialist society is that within socialism, society follows the idea of "to each according to their contribution![]() ". Within communism, society instead follows "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs

". Within communism, society instead follows "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs![]() ".[12][13]

".[12][13]

Historically, most attempts at establishing socialism have turned out less than ideal, often turning into horrifying dictatorships. Many socialists tend to promote methods of implementation that differ from the ones used in these dictatorships, hoping to avoid the mistakes of the past. Others argue these regimes were actually vibrant democracies, and figures such as Stalin were the good guys, injustly framed by the bourgeois media. That, or they were only bad because of Western sabotage.

Context[edit]

In the developed world![]() during the Industrial Revolution, workers often felt underpaid for their labour, and dangerous working conditions became commonplace.[14] This laid the foundations for the modern idea of "socialism,"[note 1] which advocated for a better society where the workers would be liberated from such harsh conditions brought by capitalism.[3]

during the Industrial Revolution, workers often felt underpaid for their labour, and dangerous working conditions became commonplace.[14] This laid the foundations for the modern idea of "socialism,"[note 1] which advocated for a better society where the workers would be liberated from such harsh conditions brought by capitalism.[3]

While the need for a radical change in the system has grown weaker in the last few decades, partly due to the acquisition of stronger labor rights and better conditions for a large part of the population, support for socialism still exists.[15] While different variants of socialism may advocate for different goals, most of them aim to fix some major perceived issues within capitalism, including economic inequality and concentration of power in the wealthy, exploitation of workers and underdeveloped countries, production for profit at society's expense (aggravating issues such as poverty and climate change), and so on.[5][4][16][17]

Proponents of capitalism consider a radical change of economic system to be unneeded. On the reformist and more left-leaning side, defenders may agree unregulated capitalism indeed features major flaws, but argue these issues can be fixed or greatly mitigated by letting the government become more involved in the economy without abolishing capitalism. These can advocate for policies such as welfare programs, stronger regulations for private enterprises (including greater labor, environmental and antitrust![]() laws) and partial, rather than full, public ownership, as is the case for modern social democrats. They believe a system like this is more ideal than full socialization, citing the failures of socialist attempts throughout history and the success of reformist practices in countries like Sweden.[18]

laws) and partial, rather than full, public ownership, as is the case for modern social democrats. They believe a system like this is more ideal than full socialization, citing the failures of socialist attempts throughout history and the success of reformist practices in countries like Sweden.[18]

On the more "purist" side (including, for example, right-libertarians), they may claim some of the critiques to be nonissues or highly exaggerated. For example, they may defend economic inequality being good for economic growth and prosperity,[19] poverty actually being the fault of "poor people not working hard enough".[20] or even that externalities which harm the climate aren't actually a big deal as "climate change is a commie hoax".[21][22][23] Meanwhile, others in the same camp might recognize the difficulties the modern status quo faces, but instead argue how it's the lack of capitalism that is the problem. They may believe issues like inequality and monopolies are actually caused by the government distorting the infallible free market, with the true remedy being economic liberalization, instead of interventionism or a full system transformation.[24]

Economic models[edit]

Different socialists propose different methods of organizing an economy. The following is a summary of how different types of economies would work within a socialist context. Note that some of the proposals shown have few to no examples of them in practice, meaning they remain mostly speculative and lack empirical data on their feasibility.

Planned economy[edit]

A planned economy is a type of economic system where production, distribution and investment is predominantly done according to economic plans rather than through the market and its participants. Plans may determine which and how many goods need to be produced, who produces them and what resources they will have available, how these goods will be distributed and to who, what will be the prices of these goods (if any), etc.[25][26]

Central planning[edit]

A centrally planned economy, often called a command economy, is a form of planned economy where economic plans are made by a central body, normally the state bureaucracy. Individual central planners design the plans based on the information they have available about the productive capacity of firms and the national demands.[5][4]

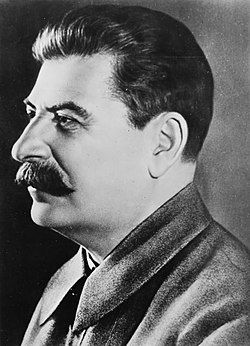

This socialist model is arguably the most (in)famous, being the face of socialism throughout the whole world. Command economies have been popularized by the Soviet Union and the Soviet model of economic planning, later adopted by various other nations such as Cuba and most countries from the Eastern Bloc.[27][note 2] The first five-year plan in the USSR was implemented under Joseph Stalin, with results of catastrophic proportions, leading to one of the worst famines in history.[30] Later central planning performances, while not as destructive, still struggled with rampant authoritarianism and various economic problems such as shortages and irrational allocation.[31][32][33]

Unsurprisingly, central planning has received its fair share of negative academic reactions. Some of the most notable critiques come from economists of the Austrian school, particularly by Friedrich Hayek. One of Hayek's major critiques include the difficulty of gathering and using relevant information, which is tacit and dispersed in a whole economy, due to the lack of price signals![]() for conveying such information.[34] Another critique by him is the inevitability of central planning to result in authoritarianism, since the kind of power that comes from planning would inevitably give great coercive powers to the state, enabling it to act in the benefit of the state bureaucracy at the expense of society as a whole.[35] Other scholars note that, even assuming central planners possess the correct information about the economy, central planning may also lead to a "bureaucratization of economic life", as these planners may lack the incentives to act on that information, a problem resolved by market economies through pressure from competition and profit as a reward for success.[36]

for conveying such information.[34] Another critique by him is the inevitability of central planning to result in authoritarianism, since the kind of power that comes from planning would inevitably give great coercive powers to the state, enabling it to act in the benefit of the state bureaucracy at the expense of society as a whole.[35] Other scholars note that, even assuming central planners possess the correct information about the economy, central planning may also lead to a "bureaucratization of economic life", as these planners may lack the incentives to act on that information, a problem resolved by market economies through pressure from competition and profit as a reward for success.[36]

Some leftists have taken this criticism for a bourgeois attack against the glorious socialist states and their extremely efficient economies.[37][38] Others have abandoned the Soviet model of planning, but still advocate for alternative models involving central planning that are (hopefully) more democratic and efficient. One such example is the model of planning through supercomputers described by Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell.[39]

Decentralized planning[edit]

As the name suggests, decentralized planning (often called "participatory" or even just "democratic planning") proposes a form of horizontal and bottom-up economic planning, aiming to fix some core issues with central planning while still avoiding common problems from market economies such as market failures.[5][4][40] This model distinguishes itself from the market mechanism, the other decentralized method of coordination, by having interdependent decisions be made collectively and in advance, instead of being done atomistically and in isolation like in the market.[40]:170–171[41]:24

Its advocates commonly propose utilizing council democracy and more federalist and self-managed forms of economic organization. A well-known modern proposal is participatory economics![]() (or "parecon"), by the economists Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, featuring a system of negotiation between federated workers' and consumers' councils, intermediated by a specialized agency meant to facilitate the planning process.[40] Proposals in a similar vein have also been presented in the past, notably in the works of Anton Pannekoek and then later of Cornelius Castoriadis. Participatory planning was also put in practice, to an extent, in the socialist experiments of the Paris Commune and Spain during the Spanish Civil War.[42]

(or "parecon"), by the economists Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, featuring a system of negotiation between federated workers' and consumers' councils, intermediated by a specialized agency meant to facilitate the planning process.[40] Proposals in a similar vein have also been presented in the past, notably in the works of Anton Pannekoek and then later of Cornelius Castoriadis. Participatory planning was also put in practice, to an extent, in the socialist experiments of the Paris Commune and Spain during the Spanish Civil War.[42]

Though there's not much empirical data available on their performance, some discussion and speculation has been made. For example, market socialist economist Alec Nove, responding to older forms of democratic planning, has argued how there is no alternative to the market for horizontal coordination, as a voting process would be impracticable due to the sheer scale of an economy and could also devolve into a majority tyranny, further criticizing the vagueness of assertions by Marxists that "society would decide what to produce" and arguing such an ideal would inherently require centralization and hierarchy.[43] Critics of parecon may also invoke similar sentiments to the first point, arguing the planning procedures would be too cumbersome and time-consuming for the average person, though its creators deem such critiques to be exaggerated, offering various suggestions to make the process easier and arguing the amount of paperwork needed wouldn't be much more than under capitalism.[4][40]:163–172

Market economy[edit]

A market economy is one where the production and distribution of goods and services is determined by the forces of supply and demand through price signals.[44] While socialism is often associated with planning, the idea of social ownership is by no means incompatible with markets. In fact, market socialists have existed before socialism was even popularized by Marx and later socialist experiments.[45]

Historically, a form of market socialism has been practiced in Yugoslavia. While the means of production were publicly owned, the actual management of enterprises was, for the most part, done by the workers themselves.[46] Under Tito, Yugoslavia did actually enjoy a relatively healthy economy, with no major shortages of consumer goods, in contrast to the many other socialist regimes of that time (though the same can't really be said on the "democracy" department). Yugoslavia's economy suffered from major downturns in its later years, however. Considering its many reforms and peculiarities, it's hard to tell whether it was because of fundamental flaws of market socialism or not.[46]:193 Yugoslavia was eventually dissolved after major internal ethnic conflicts.[47]

The current system found in China is officially named "socialism with Chinese characteristics" and features predominant use of markets, but it might more closely resemble a form of state capitalism,[48] as it still features private property. The Lange model,![]() idealized by Oskar Lange during a debate with Friedrich Hayek, is often regarded as an important market socialist model, though perhaps erroneously, as the model was created with the intention of replacing the market with planning.[49]:252

idealized by Oskar Lange during a debate with Friedrich Hayek, is often regarded as an important market socialist model, though perhaps erroneously, as the model was created with the intention of replacing the market with planning.[49]:252

Many on the left in the modern day have proposed different models of market socialism, including John Roemer's model of "coupon socialism"[50] and David Schweickart's model of "economic democracy".[51] Some influential figures, such as American politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have advocated for a market socialist system.[52] Interestingly, even some Marxists have advocated for a market socialist economy, including the economist Richard D. Wolff.[53]

Ideologies[edit]

Utopian socialism[edit]

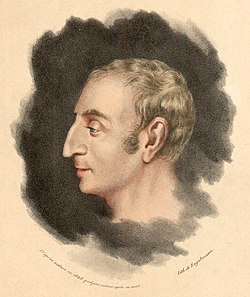

The first person who theorized of the initial modern concept of socialism was Henri de Saint-Simon,![]() a political, social, and economic philosopher. The term socialism itself was coined in 1832 by a follower of Simon, Pierre Leroux, when describing the system Simon had theorized.[54] The term "utopian socialism" was coined by Karl Marx to refer to those who generally believed in a classless and stateless society but had not hammered out any specific theories for getting there.[55]

a political, social, and economic philosopher. The term socialism itself was coined in 1832 by a follower of Simon, Pierre Leroux, when describing the system Simon had theorized.[54] The term "utopian socialism" was coined by Karl Marx to refer to those who generally believed in a classless and stateless society but had not hammered out any specific theories for getting there.[55]

Utopian socialism is also among the earliest forms of theorized and practiced socialism globally. A group known as the Owenites, followers of 19th-century Welsh social reformer Robert Owen, formed several utopian socialist communities organized along communitarian and cooperative principles. The most famous of the communities located in New Harmony, Indiana, was where Owen himself chose to reside.

The Owenite communities largely failed in short order (New Harmony's Owenite community only lasted two years). Still, Owenism is largely thought to have been the first socialist movement in American history,[56] and former Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both attended his lectures.[57] While the Owenites largely failed in their goals, Owen's ideas on labor vouchers influenced later socialist thinkers such as Daniel De Leon, while the Owenites' most lasting legacy on the socialist movement is most likely the cooperative movement.[58]

Blanquism[edit]

Blanquism refers to the short-lived socialist current derived from the ideas of Louis Auguste Blanqui. Blanqui's volunteerist, populist, and education focused view held that a dedicated revolutionary secret society could lead a popular uprising, during which time a radical republican regime could be established with the support of a patriotic populace.[59][60]

Blanquists were an influence to the socialist experiment of the Paris Commune. But, contemporarily, Blanquism is only really mentioned in comparison to Leninism and its offshoots, which similarly advocated for a small group of trained revolutionaries to lead the revolution and seize power (in the case of the latter, through the vanguard party), though Leninists will often distinguish the two by arguing the party was simply an "extension of the worker-class".[note 3]

Anarchism[edit]

“”To be governed is to be kept in sight, inspected, spied upon, directed, law-driven, numbered, enrolled, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, estimated, valued, censured, commanded, by creatures who have neither the right, nor the wisdom, nor the virtue to do so.

|

| —Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, The General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century (1851).[61] |

Anarchism is an ideology which advocates for the replacement of hierarchical authority and subordination with self-management and voluntary association within and between groups of people. It is also often defined solely for its opposition to the state and government, though some anarchists believe this characterization to be limited.[62] This is especially important in regards to anarcho-capitalism. While anarcho-capitalists argue it is a legitimate form of anarchism due to its opposition to the government, anarcho-socialists may believe that capitalism is incompatible with anarchism due to the former requiring hierarchies and disparities of power between different economic classes.[63]

Anarchism is a wildly varied ideology. The first self-styled anarchist was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon,![]() who was also the first mutualist, an anarchist school of thought. Other influential figures include the anarcho-collectivist Mikhail Bakunin

who was also the first mutualist, an anarchist school of thought. Other influential figures include the anarcho-collectivist Mikhail Bakunin![]() and the anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin, who both created/popularized their respective anarchist ideologies and advanced some of the fundamentals followed by most anarchist in the current age. Anarchism has also inspired movements in various countries, such as the anarcho-syndicalist one in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and the anarcho-communist one in Ukraine during the Ukraine War of Independence.

and the anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin, who both created/popularized their respective anarchist ideologies and advanced some of the fundamentals followed by most anarchist in the current age. Anarchism has also inspired movements in various countries, such as the anarcho-syndicalist one in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and the anarcho-communist one in Ukraine during the Ukraine War of Independence.![]() [64]

[64]

This ideology is often a victim of strawmanning by political opponents. One common misrepresentation is that anarchists support "absolute freedom", meaning there wouldn't be restrictions for any sort of crimes. Anarchists consider many crimes (including murder, theft, rape, etc.) to be "violations on the freedom of others", meaning those would be prohibited much like in current society, but with alternative systems of enforcement which don't require a state.[65] Conversely, anarchism shouldn't be confused with a mobocracy, as the main anarchist principles are based on voluntary association, with coercion only being used to deter the previously mentioned violations. Additionally, most anarchists don't oppose organization, nor do they expect everyone to vote on the most menial decisions at all times, as they favor federations of communes and temporary delegates for administrative positions which can be recalled at any time by the people that chose them.[66]

For actual critiques, one of them is on its infeasibility, particularly when considering the lack of successful, large-scale experiments which prove an anarchist society could deal with the various political and economic complexities without the reemergence of the state (or any other hierarchical or coercive mechanism anarchists despise). In addition, most anarchist movements historically were short-lived, taken down by external opponents or internal sabotage and infighting. However, whether this is the fault of the movements themselves or simply because of unique circumstances is debatable, considering how, for example, the Makhnovshchina Ukrainian movement was managing its fight against the White Army relatively well, only falling after the Red Army ganged up on it.[67]

Anarchists have also been criticized for terrorism and other brutally violent tactics. Many of these tactics were influenced by the "propaganda by the deed", a type of direct action intended to influence public opinion by serving as a catalyst for social revolution.[68] Other examples of anarchist violence include the killings and tortures in the Spanish Civil War, in which the anarchists were involved,[69] as well as the 1919 United States anarchist bombings,![]() one of the inciting incidents of the first Red Scare. Regardless, it's worth mentioning pacifist anarchists do exist, such as the Christian writer Leo Tolstoi.[70] Less pacifistic anarchists may still aim to minimize violence and instead favor other forms of direct action such as mass strikes, only making exceptions in cases where violence is required for "self-defence against oppression and authority".[71]

one of the inciting incidents of the first Red Scare. Regardless, it's worth mentioning pacifist anarchists do exist, such as the Christian writer Leo Tolstoi.[70] Less pacifistic anarchists may still aim to minimize violence and instead favor other forms of direct action such as mass strikes, only making exceptions in cases where violence is required for "self-defence against oppression and authority".[71]

Marxism[edit]

“”The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

|

| — Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Communist Manifesto (1848).[72] |

In contrast to utopian socialism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels formulated what they called "scientific socialism".[55] This variant of socialism came to be from an analysis of the history of civilization based on class struggle and historical materialism. They believed that the conditions created by capitalism would result in the conflict between the ruling class (the bourgeoisie, i.e. the class that owns the means of production) and the ruled class (the proletariat, i.e. the class of wage-earners who only own their own labor-power) which would build the foundations for a proletarian revolution where the workers would gradually seize the means of production.[72][73][74]

Marx believed that all socio-political orders, except in the mythical pure communism, were "dictatorships" in which one class dictated to the rest; the bourgeoisie was assigned that role in his characterization of capitalism. For Marx, the path towards communism would not be any less a dictatorship, but it would be a "dictatorship of the proletariat" where the workers would dictate to everyone else. The term "dictatorship of the proletariat" was initially coined to differentiate between Marx's idea of a grass-roots worker-run state and the more elitist ideas of Blanquism; but the "dictatorship" part is not meaningless, since he said in the Communist Manifesto that this dictatorship would have to resort to "despotic" measures at first (e.g., control the army to conquer other capitalist territories).[72] Engels also advocated for the state to be used "not for the purpose of freedom, but of keeping down its enemies".[75]

After the dictatorial period, society would then begin to transition towards a classless, stateless and moneyless society. "Classless" and "stateless" were tightly bound together in Marx's theory. Within Marxism, the state is defined as the tools of class oppression and subjugation,[76] meaning a society without social classes would, consequently, have no state.[77][note 4] As the socialist order is established, Marx divided what he called the lower and higher phases of a communist society, with the main distinction being that the lower phase would use labor certificates![]() as a basis for reward, while the higher phase would distribute according to need.[13] Traditionally, these phases would simply be called "socialism" and "communism" respectively. However, Marx used both terms interchangeably. Only later would Marx's ideas be reinterpreted to separate the two definitions, making socialism this transitory phase (and also fusing the lower phase with the dictatorship of the proletariat, which initially preceded the phases of communism).[49]:90–91

as a basis for reward, while the higher phase would distribute according to need.[13] Traditionally, these phases would simply be called "socialism" and "communism" respectively. However, Marx used both terms interchangeably. Only later would Marx's ideas be reinterpreted to separate the two definitions, making socialism this transitory phase (and also fusing the lower phase with the dictatorship of the proletariat, which initially preceded the phases of communism).[49]:90–91

Marxism was arguably the most influential socialist school of thought, having inspired countless movements and theorists in history. It has also created a great amount of enemies and critics all across the political spectrum, including from other socialists. For example, the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin was an ardent critic of Marx, predicting the dictatorship of the proletariat would be seized by a small elite of false representatives of the worker-class.[79] Libertarians (and, to an extent, supporters of democracy in general) from both sides often share similar sentiments. The fact that this basically happened probably helps their case.[note 5]

Marx's ideas have also been criticized by members of the scientific community from various fields. The philosopher Karl Popper has criticized Marxism on the grounds of it not being scientific (contrary to what "scientific socialism" might suggest) and its reliance on historicism.[81][82] Marxism also sees little relevance in mainstream economics, with most economists rejecting the ideas put forth on Marx's economic works (such as Capital).[83][84] Despite this, it still finds some relevance in the social sciences more broadly, with 18% of American professors in the field identifying themselves as Marxists, according to a 2007 survey.[85] Scholars who describe themselves as such may follow more "updated" traditions, which includes Analytical Marxism,![]() a variant of Marxism largely prompted by the philosopher G. A. Cohen and other members of what was endearingly called the "Non-Bullshit Marxism Group".[86]

a variant of Marxism largely prompted by the philosopher G. A. Cohen and other members of what was endearingly called the "Non-Bullshit Marxism Group".[86]

Marxism is also used as a boogeyman by right-wing cranks and fascists in various conspiracy theories, notably in Cultural Marxism. It's common for these groups to make baseless accusations against those to the left of them by claiming they're actually secret Marxists trying to bring communism through progressive policies. Tactics like these were also used during the American Red Scares.![]()

Leninism[edit]

“”Attention, must be devoted principally to raising the workers to the level of revolutionaries; it is not at all our task to descend to the level of the “working masses.”

|

| — Vladimir Lenin, What Is To Be Done? (1901).[87] |

Leninism was the current which spawned from the Bolshevik revolutionary Vladimir Lenin's works and interpretations of orthodox Marxism leading to, and after, the Russian Revolution, which occured in during the beginning of the 20th century.

Lenin was an extensive critic of "evolutionary socialism," a current developing within his time. Evolutionary socialists, such as Eduard Bernstein,![]() promoted the idea of a gradual change towards socialism. They believed that, since the conditions of the workers actually improved as the years went by, it was indeed possible to implement socialism without a revolution.[3]

promoted the idea of a gradual change towards socialism. They believed that, since the conditions of the workers actually improved as the years went by, it was indeed possible to implement socialism without a revolution.[3]

In contrast, Lenin advocated for a violent revolution as the only means to achieve socialism, arguing the improvement of conditions was due to the exploitation of poorer countries, condemning Bernstein of being revisionist. Ironically, Lenin himself held positions which went against traditional Marxist beliefs, such as how he wished to skip capitalism and go straight to socialism, rejecting the notion that a period of capitalism would be needed to develop both the productive forces of the country and the revolutionary proletariat.[3]

Lenin considered the dictatorship of the proletariat to be democratic, but also argued that the "exploiters and oppressors of the people" should be excluded from democracy, with democracy for all only being possible after reaching a classless society.[11] In practice however, the worker's state was mainly controlled by the Communist Party rather than the workers, meaning that, in the end, there was no democracy at all.[88]

Lenin was distrustful of a spontaneous revolution, i.e. that the workers themselves would realize how wonderful communism is through the natural development of history, which was the prediction made by the more traditional Marxism. Instead, he promoted the use of a central "vanguard party", organized through democratic centralism. The vanguard party was to be composed of the most class-conscious and intelligent members of the worker-class, who would bring the masses to the revolution by spreading revolutionary thought and would seize the power from the ruling classes.[88][87][89]:13–14 Democratic centralism was (on theory) based on "freedom of discussion, unity of action", where discussion was completely permitted until a decision was made by a vote from the party, in which case any actions which may derail the reached resolution are strictly forbidden.[90][89]:13–14

Critics may argue how such method of organizing the revolution is not only oppressive towards dissident members due to the nature of democratic centralism, but can lead to the alienation of the worker-class as a whole in favor of the small minority of "great thinkers" leading the revolution's vanguard, which is exactly what happened in practice.[91]

Marxism-Leninism[edit]

Marxism-Leninism is the communist ideology created by Joseph Stalin, according to his own interpretation of Marxism and Leninism. Marxism-Leninism advocates for a centrally planned economy with a one-party socialist state and brutal repression of anything deemed "bourgeois" or "counter-revolutionary", which, for virtually all Marxist-Leninist leaders, includes anyone or anything they don't like.[92]

Marxism-Leninism became the official state ideology of the Soviet Union, as well as many communist regimes following Stalin's rule. Many different ideologies can be found within it, including Stalinism under Joseph Stalin, Maoism under Mao Zedong, Juche under Kim Il-sung, and so on, each altering or adapting Marxism-Leninism in different ways under different contexts. It's one of the most followed communist ideologies to date, with many of the former and existing self-described socialist states advocating it in some form.[93]

From the Great Purge and Holodomor of Stalin to the "Year Zero" of Pol Pot, most Marxist-Leninist societies featured some kind of event leading to mass death as a result of abuse of power. Similarly to fascism, there are still those who deny the atrocities committed under these regimes, including Grover Furr and Michael Parenti. Apologists of these regimes may pejoratively be called tankies, in reference to those who were in support of the Soviet Union sending tanks to stop protests, such as the ones in Hungary during 1956.[94]

As the state controlled speech, so too was science controlled. This came from a desire to follow the principles of Marxism and dialectical materialism to a tee while avoiding all the "bourgeois pseudoscience". This was especially notorious in the Soviet Union under Stalin, where publications in scientific journals and books, granting of degrees, promotions and demotions, and so on, were all controlled by the Party. This also resulted in stuff like the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics to be labeled bourgeois.[95]:122–123 It also gave rise to the pseudoscience of Lysenkoism, a modified version of the Lamarckian evolutionary theory used for biology research and "agricultural techniques".[96] Despite Trofim Lysenko's theories being a load of bullshit dressed in the garb of dialectical materialism, this still didn't prevent him from becoming highly influential, almost turning into a "dictator" of his field.[95]:124–127 Science was still used for political purposes even after Stalin's rule, like how the Soviet Union utilized a made-up diagnosis named sluggish schizophrenia![]() against political dissidents, with these "patients" being deprived of their basic rights.[97]

against political dissidents, with these "patients" being deprived of their basic rights.[97]

It's claimed by many anti-Soviet socialists that these Marxist-Leninist regimes were a departure from socialism, on account of the means of production being in the hands of an undemocratic state instead of the workers. Many of these critics argue these regimes were a form of "state capitalism", as they did not erase the general relations of management and ownership which exist in capitalism (i.e. a small unaccountable minority owning the means of production and telling the workers what to do).[91][98][99] On the other hand, Stalinists would argue that these parallels were all fabrication by the oppressive bourgeois media and then send thugs to beat up anyone who said otherwise.

Trotskyism[edit]

Leon Trotsky attempted to become the leader of the Soviet Union after Lenin died, but was defeated by Stalin and later exiled. Initially, the key difference between Stalinism and what later became known as Trotskyism was whether the socialist revolution should be exported to other countries as quickly as possible ("permanent revolution", as advocated by Trotsky) or if socialism should be strengthened in a single country before ("socialism in one country", as advocated by Stalin). Later on, Trotsky would harshly criticize the Stalinist rule of the USSR, calling it a "degenerated worker's state" taken over by the bureaucracy.[100] He didn't denounce his Leninist principles, however. In fact, Trotsky's followers tend to believe they're the true heirs of Lenin's ideas.[89]:14

Contemporarily, Trotsky became a figure of the anti-Stalinist left,![]() sometimes even being considered a more democratic alternative to Stalin.[101] An obvious example of this in practice is how George Orwell made an allegory of Trotsky as the opposition against the tyrannical figure of the story in two separate occasions, first with Snowball in Animal Farm and then with Emmanuel Goldstein in Nineteen Eighty-Four, despite Orwell himself being doubtful that Trotskyists were morally superior to other communists.[102]

sometimes even being considered a more democratic alternative to Stalin.[101] An obvious example of this in practice is how George Orwell made an allegory of Trotsky as the opposition against the tyrannical figure of the story in two separate occasions, first with Snowball in Animal Farm and then with Emmanuel Goldstein in Nineteen Eighty-Four, despite Orwell himself being doubtful that Trotskyists were morally superior to other communists.[102]

These doubts do hold weight, as Trotsky was himself part of the leadership of the Soviet regime from 1917 to 1922, the period which featured the dissolution of the elected constituent assembly by the Bolsheviks and the outlawing of all other parties, as well as factions within the Communist Party itself. He would later defend these actions as "temporary" necessities caused by the context of the Civil War. To his credit, he would also criticize how "the prohibition of other parties, from being a temporary evil, ha[d] been erected into a principle", advocating for the reintroduction of rivalling parties and factions.[89]:15–16

Aside from the regular Trotskyists, there are also more bizarre and niche Trotskyist movements. One of the most notorious is Posadism, which affirms a nuclear war is both inevitable and desirable, arguing it would be the perfect opportunity for the socialist revolution to happen.[89]:663–664 It's also known for adopting elements of Ufology in a Marxist conception, despite its actual importance to the ideology being overblown.[103]

Libertarian socialism[edit]

Libertarian socialism, also named left-libertarianism, is the most anti-authoritarian form of socialism. While anarchism is found within libertarian socialism and both terms are frequently used interchangeably, not all libertarian socialists call themselves anarchists, preferring instead a limited government rather than a complete abolition of it.[64]:13, 641

Some of the most prominent libertarian socialist theorists can be found within the libertarian Marxist tradition, which emphasizes direct democracy and autonomy in a Marxist conception. Within this tradition are included Rosa Luxemburg and the council communists, who were both contemporaries of Lenin but critical of his ideas. Another example is Daniel De Leon, who was heavily inspired by anarcho-syndicalism.[104] Another important figure in libertarian socialism is Murray Bookchin and his communalism, which later influenced the political system of Rojava. Bookchin's communalism was based on libertarian municipalism, where each municipality would be largely autonomous in managing its own affairs and would be connected with each other through a confederation.[105]

Due to their similar natures, the critiques against anarchism can be made against libertarian socialism as well, though to a lesser extent in its more moderate variations. In addition, right-libertarians often criticize left-libertarians for not actually advocating for liberty. The libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick argued that, for an egalitarian society much like socialism to exist, it would require forbidding "capitalistic acts between consenting adults", thus undermining freedom. The analytical Marxist philosopher G. A Cohen contested this, arguing that inequality itself becomes disparities between power, which diminishes the liberty of the majority in favor of the wealthy and property-owning minority. He further argued that most of these acts shouldn't be considered "consensual", as the workers have no other choice but to subordinate to a property-owner under the threat of starvation.[106]

Democratic socialism[edit]

Despite socialism being intended to be democratic, various socialists may prefer to use the term "democratic socialism" in order to convey the goal of socialization of the means of production through an accountable democratic government more clearly, in contrast to the many dictatorships that claim to have their people's best interests in mind.[107][108] The term is frequently used interchangeably with social democracy, though the latter most often refers to reforms within capitalism inspired by socialism, rather than a fundamental systemic change.[107][108]:447

Plenty of folks have declared democratic socialist views but have had their views misconstrued with time, including Nelson Mandela,[109] Albert Einstein,[16] Pablo Picasso,![]() [110] Helen Keller,

[110] Helen Keller,![]() [111] Martin Luther King,[112] and George Orwell.[113] Other big-name self-described democratic socialists include British politician Jeremy Corbyn[114] and American politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.[52] Former Chilean president Salvador Allende has also been described as democratic socialist, being one of the few Marxist leaders actually elected by democratic means.[115] Bernie Sanders calls himself a democratic socialist, although that label has been contested.[116]

[111] Martin Luther King,[112] and George Orwell.[113] Other big-name self-described democratic socialists include British politician Jeremy Corbyn[114] and American politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.[52] Former Chilean president Salvador Allende has also been described as democratic socialist, being one of the few Marxist leaders actually elected by democratic means.[115] Bernie Sanders calls himself a democratic socialist, although that label has been contested.[116]

Various anti-socialists believe socialism is inherently incompatible with democracy. Milton Friedman argued the introduction of socialist central planning paves the road to totalitarianism, as the state would possess the ability to command the economy in favor of the elite behind the plans.[108]:447 However, this argument ignores how democratic socialists largely oppose the Soviet economic model, preferring instead a market socialist or a marketless participatory economy. Some even argue how it's capitalism that is incompatible with democracy, with its fair share of corporate meddling present in elections and policy-making.[108]:448

Religious socialism[edit]

Marxism explicitly criticizes religion, with Marx referring to religion as "the opium of the people"[note 6] to which a pre-socialist state of existence has given rise. Communists have made heavy persecutions of churches when in power, and in some cases even banned religion altogether. Anarchists are also known for their anti-clerical church-burning activities (although not all anarchists perform such behavior, and some are actually Christians themselves).

But Marx did not advocate the banning of religion, instead saying that it is simply a way to cope, and to see something bright at the end of the tunnel when one is faced with the injustices of feudal and capitalist society, and says that the criticism of religion is thus the criticism of the conditions that breed it.

There are also currents of religious socialism, as will be mentioned right now.

Christian socialism[edit]

It's not uncommon for fundamentalists to argue socialism is incompatible with Christianity. However, the tradition of Christian socialism isn't a new one. In fact, one could even argue a major player in the Bible actually advocated for something similar to socialism. As to who this figure is, here's a few hints: he is generally portrayed as a tall, blue eyed white man with long hair, wearing a flowing robe, or nailed to a cross, although he was more likely short, had short hair, brown skin, brown eyes and would have never worn a robe, as it would have been a terrible hazard in his carpentry work. A few quotes:

Verily I say unto you, That a rich man shall hardly enter into the kingdom of heaven. And again I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.

- Matthew 19:24 (KJV)Do not store up your treasures on earth, where moth and rust consume and where thieves break in and steal; but store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust consumes and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart is also.

- Matthew 6:19-21No man can serve two masters. For a slave will either love the one and hate the other, or be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth.

- Matthew 6:24Sell all your possessions and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.

- Matthew 19:21Then the King will say to those on his right, 'Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.' "Then the righteous will answer him, 'Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you something to drink? When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you? When did we see you sick or in prison and go to visit you?' "The King will reply, 'I tell you the truth, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me.'

- Matthew 25:34-40The love of money is the root of all evil."

- 1 Timothy 6:10

As recounted in Acts 2:44-45, the early Christian church practiced a form of religious communism with "all things common."[note 7] Today, there are many Christian socialist throughout the world, particularly in South America, which hold that the teachings of Jesus Christ and Marx line up nicely, and see Christ as a great social reformer and the first socialist agitator. However, these people have been criticized for equating the poor, spoken of at length by Jesus, with Marx's proletariat; specifically, Jesus said, "For the poor always ye have with you" (John 12:8), while Marxism aims to do away with the proletariat altogether. There are also small Christian groups such as the Hutterites who also practice a form of voluntary religious communism. Monasteries and other similar religious institutions may also do so.

Oddly enough, his message has been largely ignored by some of his North American followers, who seem to think he was actually ye olde Ronald Reagan or a long-haired John Galt. Cognitive dissonance sure is great, isn't it? Although in their defense, Jesus never said give your money to the poor through government. He talked about private self-decided socialism. Of course, they don't do that either.

Not-Socialism[edit]

The term socialism has a long history of gatekeeping, especially by the radical left, be it anarchists not considering any kind of state socialism to be socialism at all, or Marxists calling anything that doesn't align exactly with (their interpretation of) Marx's theories as a bourgeois distortion. However, sometimes people might get too inclusive with the term socialism, to the point where it becomes a meaningless term, be it for a red-baiting tactic, to invoke a message of "I care for the workers", or as a way to not be associated with certain controversial figures.

National Socialism[edit]

“”First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a socialist.

|

| —Martin Niemöller, about the persecution by the Nazis, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[118] |

National socialism, also commonly known as Nazism, was the ideology practiced by Adolf Hitler during his leadership of Germany. Some on the right, such as Dinesh D'Souza[119] and Elon Musk,[120] have tried to argue the Nazis were actually socialists, thus putting the blame of the horrors of Nazism on the left instead of the far-right. While one might assume that the Nazis are socialist based on their name alone, there are many reasons that prevents them from being so.

For one, the Nazis upheld private property. While fascism historically advocated for extensive government interventionism to attend the interests of the state, the Nazi economy in actuality functioned through a mix of state and private economic incentives, with avaliable sources making it perfectly clear the Nazis' goal wasn't to have many or all enterprises be owned publicly.[121]:405 In fact, reprivatization was furthered wherever possible, while state ownership was avoided unless absolutely necessary.[121]:406 Privatization is, of course, the last thing most socialists would want in order to actually socialize the economy.[citation NOT needed]

Another key reason is that the Nazi ideology includes the existence of "slave-races" who would perform all the menial tasks a society would need, while the "superior" Germans would have generous social welfare and careers for themselves only. While generous careers and welfare are indeed major goals of most socialists, they also emphasize equality: no one should be systemically underprivileged and exploited. However, one could argue this kind of society was merely "transitory", and that the ultimate goal was to exterminate these "undesirable races", at which point, depending on how society would develop afterwards, the Germans could live in some bizarre and vile form of socialism... until they just declared that the grey-eyed and/or strawberry-blonde Germans to be insufficiently German and they are back to slavery again.

Finally, Hitler and his party also continuously persecuted the left-wing of Germany, ranging from the more radical communists to even the more moderate social democrats.[122] He also demonized the Jews by claiming they were secretly behind the creation and dissemination of communism, a conspiracy theory labeled "Jewish Bolshevism![]() ". The only faction of the Nazis which might've taken the "socialist" part actually seriously were the followers of Strasserism.

". The only faction of the Nazis which might've taken the "socialist" part actually seriously were the followers of Strasserism.![]() Despite this, they were still ultra-nationalists and racists, and were mostly killed off by Hitler anyways for being "dissidents".[123]

Despite this, they were still ultra-nationalists and racists, and were mostly killed off by Hitler anyways for being "dissidents".[123]

Social democracy[edit]

Unlike what virtually every socialist advocates for, most forms of social democracy explicitly endorse the preservation of capitalist relations such as private ownership. While it differentiates itself from other capitalist systems (such as neoliberalism) by advocating for a welfare state, partial public ownership and stronger labor rights, social democracy doesn't fit into the concept of collective/social ownership.[107][124] However, while not as prominently, social democracy may also be used in a similar way to evolutionary socialism, which advocated for a gradual and reformist method to overcome capitalism, in contrast to a revolution. This form of social democracy fits with the common definition of socialism, though it's mostly historical and therefore doesn't reflect the interests of most social democrats in the modern day.[125]

A figurehead of the "self-described socialist but actually social democrat" movement is Bernie Sanders. While describing himself as a democratic socialist, his policies closely align to those of social democrats. This includes his promotion of stronger labor rights and collective bargaining, progressive taxation, in addition to his general praise of Denmark and other social democratic countries, which he considers to be socialist.[116] However, Sanders has also supported worker cooperatives,[126] writing in 1976 that "in the long run, major industries in this state and nation should be publicly owned and controlled by the workers themselves",[127] a sentiment which more closely aligns with common socialist ideals.[128]

A similar case can be made with liberal socialism. An ideology which can be traced back to John Stuart Mill, it fuses the ideals of liberalism and socialism to maximize liberty, prosperity and equality, rejecting laissez-faire economics and state socialism alike. While liberal socialists support worker-controlled firms, they most often favor a mixed economy where these worker cooperatives coexist with private enterprises. The term is also sometimes used interchangeably with social liberalism and social democracy.[129]

Liberal socialists have defended its socialist characterization on the grounds that socialism has often been conceived as a moral doctrine, rather than a set of arrangements for a particular system.[130] However, it's debatable whether this understanding of socialism is correct or not, considering the history of the term and its usage to refer exactly to that set of systemic arrangements. This morality-based definition is also somewhat unclear and arbitrary as a form of categorization, further blurring the line between what can be considered "socialist" or "capitalist".

Obamunism and successors[edit]

“”Kamala vows to be a communist dictator on day one. Can you believe she wears that outfit!?

|

| —Elon Musk, on a |

Generally, the Democrats are regarded as being a centrist or center-left party. In the last few decades however, the right-wing in the US has been trying to redefine the term "socialist," with the desired meaning being, "a person who flouts the Republican party line on more than two issues."[132] U.S. President Barack Obama became the poster-boy for this sort of "socialism" during his presidency, despite having no socialistic tendencies except for introducing a reform in the healthcare system (which is arguably not even socialist, as many capitalist countries have full public healthcare).

More recently, former president Joe Biden has also been called a socialist. In 2020, when asked on an interview to address voters "worried about socialism", Biden responded by stating “I beat the socialist, that’s how I got elected. That’s how I got the nomination. Do I look like a socialist? Look at my career — my whole career. I am not a socialist”.[133] Indeed, one can wonder what exactly makes Biden a socialist. Charlie Kirk attempted to argue Biden is a socialist by effectively claiming that "socialism is when the government spends a lot of money", but the issues with this are too obvious and have already been addressed previously.[134]

Former vice-president Kamala Harris has also been called a communist and even received the nickname "Comrade Harris".[131] Donald Trump argued Harris is a Marxist on the grounds that her father is a Marxist professor in economics.[135] Her father, Donald J. Harris, is indeed well-versed in Marxian economics and has taught it in his career,[136] although there's not much evidence of Kamala Harris herself being a Marxist. Donald Trump has also called Harris's anti-price-gouging laws as "socialist price controls", despite these laws not actually proposing price controls like the ones found in existing socialist states, but rather an evaluation of corporate conduct.[137] Trump's claim also ignores how price controls aren't even inherently socialistic, as they have been used by figures such as Richard Nixon before.[138]

The only members of the Democratic Party which could conceivably be called socialists would be the ones who are members of the Democratic Socialists of America, most notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Even so, this section of the party is hardly notable in comparison to its Third Way and socially liberal sections.

Socialism and nationalism[edit]

Socialism and nationalism are typically in opposition and socialists are generally against the concept of nations, seeing them as an unnecessary division. To quote Eugene V. Debs, early leader of the SPUSA, "I have no country to fight for; my country is the earth, and I am a citizen of the world."[139] They often view nationalism as simply ways to divide the working class. Most instead advocate for "proletarian internationalism", where class struggle isn't a localized event, but a single global cause not to be separated by borders.[140]

However, this internationalism advocated by most socialists sometimes came with support for a "socialist patriotism". Lenin considered "proletarian patriotism" to be a different concept from "bourgeois nationalism", believing countries subjugated by imperialism had the right to unite and seek national liberation from oppression. Similar ideas were put into practice in various Marxist-Leninist states, where national unity was emphasized with simultaneous promotion of worldwide unity with the socialist cause.[141]

Similarly, Hugo Chávez of Venezuela has played on a patriotic and nationalistic appeal, chanting that "El pueblo unido jamás será vencido![]() " ("the people united will never be defeated") and complimenting Mahatma Gandhi for his "sane nationalism" and anti-imperialist sentiment.[142] Gamal Abdel Nasser promoted Arab nationalism, similarly advocating for national unity and anti-imperialism.[143]

" ("the people united will never be defeated") and complimenting Mahatma Gandhi for his "sane nationalism" and anti-imperialist sentiment.[142] Gamal Abdel Nasser promoted Arab nationalism, similarly advocating for national unity and anti-imperialism.[143]

There are some cases of more traditional (ultra-)nationalism in nominally socialist regimes. For example, Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge intensely persecuted various ethnic minorities, as well as Buddhist monks and educated elites, even placing more importance on race rather than class. Its level of nationalistic violence is sometimes compared to actual fascism.[144]

Notable organizations[edit]

International[edit]

International Workingmen's Association[edit]

The International Workingmen's Association, often referred to as the First International, was a left-wing organization founded in the 19th century, but dissolved in the midst of the Bakunin-Marx infighting.[145] Later on, similar organizations were created. The Second International followed, but dissolved in the midst of infighting over support of World War I.[146] The Third International (the Communist International, or Comintern) was a Soviet-funded body dissolved in World War II.[147] The Fourth International, a Trotskyist organization, still exists, though not as a singular or centralized organization.[148]

Socialist International[edit]

The Socialist International is a worldwide federation of socialist political parties, mostly consisting of democratic socialist, labor, and social democratic parties. Over thirty nations are governed by a Socialist International member-party, such as France, Iceland and South Africa. These parties are in practice social democratic or even Third Way/liberal and in recent years have experienced spectacular collapses in the face of polarization.[149]

American[edit]

Democratic Socialists of America[edit]

The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) is, as one can imagine, a democratic socialist organization. In fact, it's the largest socialist organization in America currently. While not a party per se, some members do run on elections, most often as a member of the Democratic Party, including people like AOC. They most often advocate for democratic socialist or social democratic reforms, such as increasing the minimum wage, reforming the healthcare and education system, implementing social and welfare programs, etc. Despite their name, they still have more authoritarian tendencies such as Marxism-Leninism.[150] Some members have also shown support for authoritarian figures, such as Lenin.[151]

Party for Socialism and Liberation[edit]

The Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) is a Marxist-Leninist American political party.[152][153][154] They have a pretty radical program, including stuff such as nationalizing the 100 biggest domestic corporations and cutting the military budget by 90%.[155]

They have a long history of support for authoritarian regimes. For one, they support North Korea, labeling it an "alternative to the global capitalist system" and defending it from accusations of poor human rights records, calling them "pure fantasy".[156][157][158] They also support the Chinese government and deny the Tiananmen Square Massacre, arguing the protests were funded by the US government and criticizing the testimonies of eyewitnesses.[159]

British[edit]

British Labour Party[edit]

Historically, the Labour Party were social democrats, or 'reformists', and Labour governments have made some lasting changes in terms of universal welfare, especially the founding of the National Health Service.

"New Labour" (Tony Blair etc.) were arguably conservatives in all but name, and indeed much has been said about the similarities between their policies and those of Thatcherism.[160][note 8] Clause IV of the Labour Party's constitution, which expressed a long-term commitment to redistribution of wealth and common ownership of the means of production, was rewritten in 1994, under Blair's leadership, as a more vague expression of striving for equality, causing some internal conflict and outrage from "Old Labour" socialist members of the party. In 2015, many social democrats won Labour Party contests, signaling a return to the left; there was only one actual socialist who was elected to leadership, however, although being the leader of the party, he (Jeremy Corbyn) does have a lot more say in party policy. In the run-up to the 2017 General Election the party published a report entitled Alternative Models of Ownership which tried to envision economic and business models without traditional capitalists; even though it ran its most left-wing campaign in years, envisioning more state-run corporations, universal welfare programs and public services, the party stopped far short of actively railing against capitalism in general, and in fact tried to court some businesses over Brexit.

Notable proponents of socialist theories[edit]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Although it can be argued its roots trace back to ancient history.

- ↑ Some scholars have argued that calling these economies "planned" is mistaken, as the central management was often prioritized over the plans themselves, meaning an "administered economy" would be a more accurate label.[28][29]

- ↑ See these Reddit posts for examples: "[Marxist-Leninists] Isn't Marxism-Leninism just Blanquism with Marxist window-dressing?", r/CapitalismVsSocialism; "How is Marxist-Leninism not Blanquism?", r/communism101; "Difference between Blanquism and Leninism?", r/socialism101.

- ↑ Note that the definition of state by anarchists contrasts with this Marxist definition, as they define the state as a form of minority rule. In other words, a "stateless society" in an anarchist context might not mean the same thing as in a Marxist one. In fact, certain interpretations of the "worker's state" can be very similar to what anarchists consider to be a stateless society. In these cases, anarchists argue defining these forms of organization to be a state is unhelpful and can be dangerously ambiguous.[78]

- ↑ Although some Marxists would contest that the Soviet Union was in any way actually Marxist. To their credit, Marx probably didn't have something like the Soviet Union in mind when writing about socialism, considering how he believed everyone should be part of the government, comparing it to a trade union.[80]

- ↑ Some context: in Marx's time, opium was seen (and actually is) a very effective painkiller, and at the time there was nothing more effective that opium, so he's not saying that religion is a dangerous drug, but rather a painkiller used to cope with pain.

- ↑ In fact, the phrase "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" is also an apparent paraphrase of those same verses.[117]

- ↑ On the other hand, they dramatically increased the level of public expenditure. Following the 2008 recession, the proportion of public spending in the economy hit 50% of GDP. How this level of state intervention in the economy can be considered "conservative" is anyone's guess (then again, see Dubya).

References[edit]

- ↑ Rear Platform and Other Informal Remarks in New York by Harry S. Truman (October 10, 1952) Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, National Archives.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on socialism.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Arnold, Samuel. Socialism. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed January 8, 2025.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Gilabert, Pablo; Neill, Martin (May 25, 2024). "Socialism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2025-01-09.

- ↑ socdoneleft (June 4, 2016). "Socialism Is When The Government Does Stuff". Youtube.

- ↑ Sunkara, Bhaskar (February 13, 2016). "End Private Property, Not Kenny Loggins". Jacobin. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "B.3.1 What is the difference between private property and possession?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. Vol. 1. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ Liberation Staff (November 9, 2011). "Eight myths about socialism–and their answers". Liberation News.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (February 1848). "Chapter II. Proletarians and Communists". Manifesto of the Communist Party – via Marxists Internet Archive.

Communism deprives no man of the power to appropriate the products of society; all that it does is to deprive him of the power to subjugate the labour of others by means of such appropriations.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lenin, Vladimir. "Chapter V: The Economic Basis of the Withering Away of the State". The State and Revolution – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ Gregory, Paul; Stuart, Robert (2003). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First. South-Western College Pub. p. 118. ISBN 0-618-26181-8.

Under socialism, each individual would be expected to contribute according to capability, and rewards would be distributed in proportion to that contribution. Subsequently, under communism, the basis of reward would be need.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Marx, Karl (1875). "Part I". Critique of the Gotha Programme – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ Montgomery, David. "Chapter 3: Labor in the Industrial Era". U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved December 7, 2024. "Shifting seasonal demands, crippling illnesses caused by industrial poisons, and alternating spasms of relentless work and forced idleness caused by the drive of each employer to capture as much of the market as possible--all these made for many long days without income."

- ↑ Sunkara, Bhaskar (1 May 2019). "This May Day, let's hope democratic socialism makes a comeback". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ↑ Saltmarsh, Chris (August 11, 2021). "Capitalism Is What's Burning the Planet, Not Average People". Jacobin. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ↑ Acemoglu, Daron (February 17, 2020). "Social Democracy Beats Democratic Socialism". Project Syndicate. Archived from the original on October 26, 2022.

- ↑ Winship, Scott (October 29, 2014). "Inequality Does Not Reduce Prosperity: A Compilation of the Evidence Across Countries". Manhattan Institute.

- ↑ Ferdman, Roberto A. (October 9, 2014). "One in four Americans think poor people don't work hard enough". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Challenging Knowledge: How Climate Science Became a Victim of the Cold War (preprint) by Naomi Oreskes & Erik M. Conway (2008) In: Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, edited by Robert Proctor & Londa Schiebinger. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804759014.

- ↑ Global Warming or Global Governance? by George Stamm (Aug 8, 2008) The Epoch Times via Prison Planet.

- ↑ Reuters Fact Check (August 18, 2021). "Fact Check: Climate change is not a ploy for communism; a Greta Thunberg meme has been digitally altered". Reuters.

- ↑ Patil, Soham (July 12, 2024). "The Myth of Market Failure". Mises Institute.

- ↑ Cambridge Business English Dictionary. "Economic planning". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on planned economy.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Soviet-type economic planning.

- ↑ Wilhelm, John Howard (1985). "The Soviet Union Has an Administered, Not a Planned, Economy". Soviet Studies. 37 (1). Taylor & Francis, Ltd: 118–130. JSTOR 151614.

- ↑ Ellman, Michael (2007). "The Rise and Fall of Socialist Planning". In Estrin, Saul; Kołodko, Grzegorz W.; Uvalić, Milica (eds.). Transition and Beyond: Essays in Honour of Mario Nuti. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-230-54697-4.

Realization of these facts led in the 1970s and 1980s to the development of new terms to describe what had previously been (and still were in United Nations publications) referred to as the 'centrally planned economies'. In the USA in the late 1980s the system was normally referred to as the 'administrative-command' economy. What was fundamental to this system was not the plan but the role of administrative hierarchies at all levels of decision making; the absence of control over decision making by the population [...].

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on first five-year plan.

- ↑ Nove, Alexander (May 4, 1993). An Economic History of the USSR: 1917-1991, 3rd Edition. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140157741.

- ↑ Kornai, János (1980). Economics of shortage. Amsterdam, New York: Elsevier Science Ltd. ISBN 978-0444860590.

- ↑ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (September 11, 2007). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, 2nd Edition. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415366274.

[The development strategies] involved the relative neglect of consumer needs and the service sector (with the partial exceptions of education and health care), unprecedentedly rapid urbanization, acute urban overcrowding, chronic shortages, massive recruitment of women into mostly menial and/or low-paid occupations, widespread use of coercion, repression, 'show trials', purges and intimidation, and major errors and waste in the over-centralized resource allocation and distribution.

- ↑ Hayek, Friedrich (1945). "The Use of Knowledge in Society". The American Economic Review.

- ↑ Hayek, Friedrich (1944). The Road to Serfdom. Institute of Economic Affairs.

- ↑ "Socialism". Adapted from "The World After Communism" by Robert Heilbroner, published on Dissent (Fall 1990). Econlib. Accessed May 23, 2025.

- ↑ "Why was the planned economy of the USSR so inefficient and how can its problems be avoided in the future?". r/socialism101. Via Reddit.

- ↑ "Why do people not like planned economies?". r/socialism101. Via Reddit.

- ↑ Cockshott, Paul; Cottrell, Allin (April 1, 1993). Towards a New Socialism. Spokesman Books. ISBN 978-0851245454.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Hahnel, Robin (2021). Democratic Economic Planning. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-17370-0.

- ↑ Devine, Pat (1988). Democracy and Economic Planning: The Political Economy of a Self-governing Society. Polity Press.

- ↑ Spannos, Chris (2012). "Examining the History of Anarchist Economics to See the Future". The Accumulation of Freedom. AK Press.

- ↑ Nove, Alec (1991). The Economics of Feasible Socialism Revisited (PDF) (second ed.). London: HarperCollinsAcademic. pp. 29–30, 219–221.

- ↑ Gregory, Paul; Stuart, Robert (2003). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century. South-Western College Pub. p. 538. ISBN 0-618-26181-8.

Market Economy: Economy in which fundamentals of supply and demand provide signals regarding resource utilization.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on market socialism.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Estrin, Saul (1991). "Yugoslavia: The Case of Self-Managing Market Socialism". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 5 (4): 187–194. doi:10.1257/jep.5.4.187. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ↑ Allcock, John B ; Lampe, John R (December 15, 2024). Yugoslavia. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed 19 January 2025.

- ↑ Szamosszegi, Andrew; Kyle, Cole. "An Analysis of State-owned Enterprises and State Capitalism in China" (PDF). U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Steele, David Ramsay (September 1992). From Marx to Mises: Post Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9862-6.

- ↑ Roemer, John (January 1, 1994). A Future for Socialism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674339460.

- ↑ Schweickart, David (July 23, 2002). After Capitalism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 9780742513006.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Croucher, Shane (June 18, 2019). "Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Explains Socialism During Instagram Live Stream: 'It Does Not Mean Government Owns Everything'". Newsweek.

- ↑ Wolff, Richard D. (November 7, 2022). "Economic Update: Capitalism vs Socialism is NOT Markets vs Planning". Democracy at Work.

- ↑ https://www.etymonline.com/word/socialism

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Engels, Friedrich (1880). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/cu31924030362721/cu31924030362721_djvu.txt

- ↑ Rowland Hill Harvey (1947). Robert Owen: Social Idealist. University of California Press. pp. 99–100.

- ↑ http://scholar.google.com/scholar_url?url=https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/143150/files/weavers.pdf&hl=en&sa=X&scisig=AAGBfm2zSSg4Y5rV3zYlNxXbdy4Fw5QoCQ&nossl=1&oi=scholarr

- ↑ Hallward, Peter (2014). "Blanqui's bifurcations" (PDF). Radical Philosophy.

- ↑ The Blanqui Reader, pages 202-230

- ↑ Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1851). The General Idea of the Revolution in the 19th Century – via The Anarchist Library.

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "Section A.1 - What is Anarchism?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. Vol. 1. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "Appendix -- Is "anarcho"-capitalism a type of anarchism?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Marshall, Peter (2008). Demanding the Impossible. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1.

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "Section I.5.8 What about crime?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. Vol. 2. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "Section A.2.11 Why are most anarchists in favour of direct democracy?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. Vol. 1. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Makhnovshchina.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on propaganda of the deed.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Red Terror (Spain).

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "Section A.3.4 Is anarchism pacifistic?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. Vol. 1. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "Section J.7.3 Doesn't revolution mean violence?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. Vol. 2. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1847). Manifesto of the Communist Party. Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1845). The German Ideology. Marxists Internet Archive.

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence.

- ↑ Engels, Friedrich (1847). The Principles of Communism. Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↑ Engels, Friedrich (1875). Engels to August Bebel In Zwickau – via The Marxists Archive.

The people's state has been flung in our teeth ad nauseam by the anarchists, although Marx's anti-Proudhon piece and after it the Communist Manifesto declare outright that, with the introduction of the socialist order of society, the state will dissolve of itself and disappear. Now, since the state is merely a transitional institution of which use is made in the struggle, in the revolution, to keep down one's enemies by force, it is utter nonsense to speak of a free people's state; so long as the proletariat still makes use of the state, it makes use of it, not for the purpose of freedom, but of keeping down its enemies and, as soon as there can be any question of freedom, the state as such ceases to exist.

- ↑ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1891). The Civil War in France - Engels 1891 Postscript. Marxists Internet Archive.

[..] [T]he state is nothing but a machine for the oppression of one class by another[..]

- ↑ Engels, Friedrich (1880). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Marxists Internet Archive.

As soon as there is no longer any social class to be held in subjection; as soon as class rule, and the individual struggle for existence based upon our present anarchy in production, with the collisions and excesses arising from these, are removed, nothing more remains to be repressed, and a special repressive force, a State, is no longer necessary.

- ↑ McKay, Iain; Elkin, Gary; Neal, Dave; Boraas, Ed (February 22, 2024). "H.2.1 Do anarchists reject defending a revolution?". An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15.6. Vol. 2. The Anarchist FAQ Editorial Collective.

- ↑ Bakunin, Mikhail (5 October 1873). Statism and Anarchy. Marxists Internet Archive.