Cold War

“”Under the four oceans and the seven seas, American and Soviet submarines fight a near-war every day of the year. Relentlessly, they search for one another, trailing an adversary when they can and trying to evade one when detected. They make every move of a real war, except shoot. The submarines operate in what Adm. James D. Watkins, the former Chief of Naval Operations, has called "an era of violent peace".

|

| —Richard Halloran, New York Times, 1986.[1] |

| Oh no, they're talking about Politics |

| Theory |

| Practice |

| Philosophies |

| Terms |

| As usual |

| Country sections |

|

|

The Cold War was a prolonged period of geopolitical conflict between the United States (and its allies) and the Soviet Union (and its allies). It was called a "cold" war because the two sides never directly engaged in direct full-scale war with each other, instead using diplomacy, deterrence, money, ideology, subversion and espionage, propaganda, and proxies to try to best each other.[note 1] The main reason for this was that both "superpowers" possessed nuclear weapons, which, to most sane people, made the idea of a "hot" war unthinkable. Most events of the period were related to the Cold War in some way. One of the superpowers took sides in almost every conflict, usually provoking a response from the other. Even minor things like the movement of a well-known ballet star from one country to the other became part of the superpower dick-measuring contest.[3]

Due to the nature of the conflict, it's difficult to really pin down a start or end date. The classical start date for the Cold War is 1946, after the publication of the "Long Telegram" by an American diplomat in Moscow, which convinced the US government that the Soviets were a hostile force that needed to be forcibly contained.[4][5] That said, it's also quite reasonable to place the start of the Cold War at the Yalta Conference during World War Two, when Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin diplomatically grappled with each other as to what a post-Nazi Europe would look like.[6][7] Or perhaps it began even earlier in 1943, with the US discovery of widespread Soviet industrial espionage and their subsequent retaliation.[8] The end date, meanwhile, is usually said to be either the fall of the Berlin Wall or the dissolution of the Soviet empire (Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc).

There is a recurring battle among historians over who "started" the Cold War, with traditionalists blaming Stalin and revisionists blaming Truman.[9] Most current scholars believe that between the mutual suspicion and the strongly differing plans for the post-war system, the question is really moot. When the Soviets were around, they claimed that the struggle started when a British-American coalition invaded Russia during their civil war[10][11] and tried to assassinate Vladimir Lenin (some revisionists still rock this look).[12]:185-192 Anyway, the winners get to write history, or since nuclear weapons to end it.

There is also debate today over who ended the Cold War. A certain American conservative party claims that Saint Reagan single-handedly ended the Cold War with a speech in front of a wall. However, it's mostly accepted in the reality-based community that it was a combination of internal difficulties in the USSR (namely a large military budget, ethnic tensions, and the fact that command economies are stupid), Gorbachev's attempts at reforms, a Pope, and pressure from various US presidents. It is an oft-forgotten (and inconvenient) truth that the Soviet Union's downfall was a surprise for all parties.[13][14] The popular conception that the United States defeated the Soviet Union in the Cold War had major ramifications on US foreign policy in the future.

Defeating the Soviets involved the clandestine takeover of dozens of countries and attempts to control "The Grand Chessboard" of Asia,[15] home to more than two-thirds of the world's energy reserves. Most of the wars of the past fifty years has been a runoff of this goal. Many political scientists have said that the bipolar great power system that accompanied the Cold War was very stable, and many fear that the subsequent unipolar world could end up more war-prone than before; however, many also believe that the data so far suggests otherwise.[16] The number of countries possessing nuclear weapons has steadily increased over two decades, though, so it's not all sunshine and roses.

Origins[edit]

Although most conventional histories place the beginning of the Cold War at or around the end of World War Two, it's arguable that it actually began much, much earlier than that.

Already in the nineteenth century, the French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville observed that the United States and Russia were the two nations that were still enjoying prodigious territorial growth, to such an extent that they would each dominate much of the world. Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America (1835): “Today there are two great peoples on earth who, starting from different points, seem to advance toward the same goal: these are the Russians and the ... Americans. Their point of departure is different, their paths are varied; nonetheless, each one of them seems called by a secret design of Providence to hold in its hands one day the destinies of half the world.”

Russian Civil War[edit]

Some historians believe the Cold War began as early as the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War.[17]:57 The Russian Civil War began when tsarists, liberals, Menshiviks,![]() and others teamed up to oppose the recently empowered Bolsheviks.[18] The anti-Bolshevik alliance quickly received assistance from abroad.

and others teamed up to oppose the recently empowered Bolsheviks.[18] The anti-Bolshevik alliance quickly received assistance from abroad.

Russia's former allies went so far as to invade it in order to stop the spread of communism (this should sound familiar). British troops seized Arkhangelsk in northern Russia, and American troops sent by General John J. Pershing joined them.[19] Also battling the Bolsheviks were French, Belgian, Romanian, Greek, Polish, Canadian, Italian, Japanese, Czechoslovak, Yugoslav, and Australian soldiers. Although about 13,000 US troops joined the fight, President Woodrow Wilson's vaguely-stated objectives prevented them from really doing anything, and troop morale suffered because no one really knew why they were there.[20] As always happens when foreigners invade Russia, winter cames and makes the situation unsalvageable, forcing the allies to withdraw from Russia. The intervention as a whole was bloody and pointless, and it permanently soured relations between the US and the USSR.

Hostility continued between the East and the West after the Bolshevik victory. Vladimir Lenin infamously stated that the new Soviet Union was surrounded by a "hostile capitalist encirclement" and that the Soviet Union and the world's communists would use subversion and revolution as the weapons by which they would spread their influence.[21]:62

Yalta Conference[edit]

The Soviets would later cooperate with America and the Western European democracies against Hitler and the Axis after Nazi Germany broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact![]() by attacking the Soviet Union during World War II. However, the Soviets and the Western allies fundamentally disagreed over how the postwar map of Europe should look. The democracies wanted central Europe to be shaped into democratic republics, while the Soviets wanted an array of puppet states that would buffer them from potential western threats.[17]:156 In February 1945, the allied leaders met in the Crimean city of Yalta in order to resolve these differences.

by attacking the Soviet Union during World War II. However, the Soviets and the Western allies fundamentally disagreed over how the postwar map of Europe should look. The democracies wanted central Europe to be shaped into democratic republics, while the Soviets wanted an array of puppet states that would buffer them from potential western threats.[17]:156 In February 1945, the allied leaders met in the Crimean city of Yalta in order to resolve these differences.

The Allies, who had previously agreed to divide Germany into an east and a west, also agreed that all of Germany's war industries would be dismantled, that war criminals would be tried before an international tribunal in Nuremberg, and that none of the Allies had any further obligation to the Germans than to prevent them all from starving to death.[22] In terms of the disagreements, Stalin had the diplomatic upper hand since his troops were a mere 50 miles outside of Berlin.[23] The Allies, meanwhile, had competing agendas. Churchill was focused on ensuring free elections in eastern Europe while Roosevelt was more concerned with enlisting Soviet aid against Japan to end the war in Asia.[23]

In the end, Stalin played the democratic leaders like fiddles. In return for agreeing to join the United Nations, agreeing to allow free elections in occupied Europe, and agreeing to invade Japan when the time came, Stalin got the Western powers to consent to his occupation of much of the continent and a stake in Manchuria.[24][25] After Nazi Germany fell, Stalin simply reneged on his promise to allow free elections and used his occupation forces to ensure that the nations of eastern and central Europe would become his communist puppet states.[22]

Soviet operations against Japan[edit]

In August of 1945, the Soviet Union broke its non-aggression pact with Japan and declared war on it as they had promised to do at Yalta. The Soviets immediately invaded Japan's puppet state Manchukuo (previously known as 'Manchuria') in northern China, catching the Japanese by surprise.[26] When the Japanese put up stiff resistance at the Yalu river (on the border of Manchuria and Korea), the Soviets launched naval invasions into northern Korea (then a colony of Japan known as Chōsen).[26]

Japan then surrendered shortly after the US dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. After this, the Americans landed in southern Korea and arbitrarily decided to split the peninsula along the 38th parallel, ensuring that Korea's historic capital and largest city, Seoul, was in American hands.[27] Although both sides promised to hold elections and reunify Korea, neither side trusted the other and both wanted Korea to remain ideologically aligned with them. Thus, Korea remained split and eventually became the totalitarian communist state of North Korea and the capitalist military dictatorship of South Korea.

In northern China, the Japanese had no choice but to surrender to the Soviets, who promptly handed over most of the captured weapons and territory to Mao Zedong's communist forces and gave them the upper hand in the inevitable resumption of the Chinese Civil War.[28]:338

Potsdam Conference[edit]

Back in Europe, the Allies met in the Potsdam Conference to hash out more details of their administration of Germany. However, America's new president, Harry Truman, neither liked or trusted Stalin, and the two leaders clashed over various issues.[29]:62 Stalin protested when Truman refused to allow the Soviets any influence in American-occupied Japan.[30]:28

The most pressing issue, however, was the US' use of two nuclear weapons against Japan. Stalin, likely realizing that Truman planned to use those weapons to threaten him, said that America's use of the weapons was a "superbarbarity" and that "the balance has been destroyed… That cannot be."[17]:24-26

The Cold War[edit]

Containment[edit]

The Iron Curtain[edit]

“”Nobody knows what Soviet Russia and its Communist international organisation intends to do in the immediate future, or what are the limits, if any, to their expansive and proselytising tendencies… From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.

|

| —Winston Churchill, 1946.[31] |

The rapidly souring relations between the United States and the Soviet Union created an atmosphere of confusion among US diplomats and policymakers, and the US' leaders had no real idea how to deal with a communist superpower. Hoping for advice, the US government contacted George Kennan, US Chargé d’Affaires at the embassy in Moscow in 1946. Kennan replied with what is now called the "Long Telegram", a document that permanently shaped US policy towards communism.[32] He formulated an early form of domino theory, claiming that communist nations naturally spread their ideology like a "malignant parasite" and that the US must take drastic measures both at home and abroad to stop this from happening.[33] Kennan also expanded on his points in an article published under a pseudonym, writing "the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies."[32] These helped Truman solidify his foreign policy into a doctrine that he called containment. As a result, the US finally abandoned its historical isolationism, and the US military budget increased from $13 billion in 1950 to $60 billion in 1951.[34]

Churchill, for his part, gave a speech in which he popularized (but not invented) the term "iron curtain" to describe the way that the Soviets were dragging the nations of Europe into despotism.[35] Stalin retaliated by comparing Churchill to Hitler, saying that Churchill wanted the "English-speaking nations" to dominate the world and claiming that the Soviets were simply acting in self-defense.[36]:143 The Soviet Union as a whole set the stage for its part in the Cold War by enacting the policy recommendations of the Novikov Telegram, a message sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US, Nikolai Novikov.[37] Novikov argued that the US had emerged from the war as an aspiring imperialist power that hoped to dominate the world, and saw the Soviet Union as its sole obstacle.[38]

Crises in Turkey and Greece[edit]

The two superpowers were immediately pitted against each other by events in the Balkans. The Greek Civil War erupted almost immediately after the end of Axis occupation between Greek constitutional monarchists and Greek communists.[39] Turkey also became a hot spot in 1946 when the Soviet Union demanded that they allow unlimited Soviet shipping through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits. Refusing to cave to Soviet pressure, the Turks instead chose to seek protection from the US and join NATO.[40]

Most importantly, however, these crises helped solidify Truman's containment doctrine. In 1947, Truman sent a message to Congress warning of communist expansionism, and they promptly approved $400 million for the purpose of aiding Turkey and Greece.[41] This created a pattern of US financial interventionism that would remain throughout the Cold War. US aid bolstered the right-wing forces in Greece, allowing them to eventually achieve victory in 1949.[42][43]

The Marshall Plan[edit]

In 1948, the US launched an economic aid program designed to stabilize the postwar economies of 17 countries in western and southern Europe. Although apparently an act of goodwill, the Marshall Plan was actually motivated by fear of communist expansion. US policymakers feared that poverty, unemployment, and homelessness in postwar Europe were reinforcing the appeal of communist parties to European voters. The US even offered aid to those nations occupied by the Soviet Union, likely hoping to expand their influence there, but the Soviets refused. The US distributed some $13 billion worth of economic aid, and the Europeans coordinated on their end by establishing the Committee of European Economic Cooperation, a precursor to the eventual Organisation for European Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).[44]

The Eastern Bloc shapes up[edit]

In the postwar years, the Soviets blatantly broke Stalin's promises at Yalta. Rather than allowing free elections in eastern and central Europe, the Soviets instead acted on their plan for a buffer area of puppet states.[45] They forced a communist government on Romania, cancelled elections in Poland, and executed pro-democracy advocates and politicians in Bulgaria.[46] In 1947, the Soviet Union created the Cominform, an organization nominally meant to encourage international cooperation among communist states, but in reality the legal mechanism by which the Soviets would control their puppets.[47] The Cominform effectively made the Eastern Bloc official.

Czechoslovakia was the lone Soviet-occupied country that managed to survive as a free nation. However, the Soviets were not about to tolerate that. Rather than wait for elections, communist forces staged a coup against the legitimate Czechoslovak government in 1948 and purged opposition members from government either by sending them into forced labor on collective farms or by outright murdering them.[48]

Josip Broz Tito, the communist leader of Yugoslavia, split with Stalin in 1948 and was expelled from the Cominform during the so-called Tito-Stalin split.![]() [49] Tito's nationalist tendencies led him to refuse becoming a Soviet client, and he sought to build his own sphere of influence. He went on to violently purge Stalinists from Yugoslavia and found the Non-Aligned Movement.[50]

[49] Tito's nationalist tendencies led him to refuse becoming a Soviet client, and he sought to build his own sphere of influence. He went on to violently purge Stalinists from Yugoslavia and found the Non-Aligned Movement.[50]

Berlin crisis[edit]

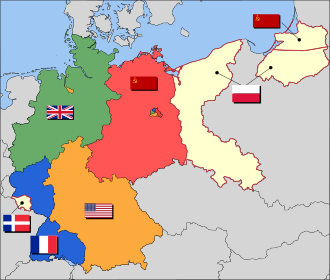

Meanwhile, the western powers merged their occupation zones in Germany while using Marshall Plan aid to rebuild its industry. The US had very quickly decided that a unified or neutral Germany was undesirable, despite the fact that the Soviets had met the preconditions set by the US for offering a new deal on Germany.[51]:67 In retaliation for the merge, Stalin imposed a blockade against West Berlin that closed all transportation routes and halted food and supply shipments.[52][53] Rather than halting political unity in West Germany, the blockade actually accelerated it. All three western powers consented to a series of conventions that drafted a constitution and created the Federal Republic of Germany in spring 1949.[54]

In response to the creation of a West German state, the Soviets held sham elections in their own occupation zone. Voters used non-secret ballots and could only choose among communist-controlled parties.[55] In fall 1949, the German Democratic Republic came into existence.[56][note 2]

The western powers also resisted the Soviet blockade of West Berlin, spurred on by a pro-western demonstration by 300,000 Berliners.[57] The US, Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several other countries began the tremendous "Berlin airlift" to supply West Berlin with food and other provisions.[58] Realizing the futility, Stalin backed down and ended the blockade.

Beginning of the nuclear arms race[edit]

“”On the morning of Sept. 14, 1954, in the Ural Mountains about 600 miles southeast of Moscow, the Soviet military exploded an atomic bomb in the air near 45,000 Red Army troops and thousands of civilians as part of a military exercise. How many people were killed or maimed or became ill as a result of the exercise may never be known.

|

| —Marlise Simons[59] |

Soviet espionage managed to obtain details of the US Manhattan Project, and in August 1949, the Soviets detonated their first atomic bomb as a test in Kazakhstan.[60] The RDS-1, as the Soviets called it, or Joe-1,[61]:371 as the Americans code-named it, was extremely similar to the "Fat Man" device the US had used on Nagasaki.[62]:164[61]:261 Meanwhile, the US was conducting nuclear tests of its own, starting with Operation Crossroads![]() in 1946, the first test since World War II[63] and the first of many tests in the Marshall Islands. In 1952, the US detonated its first hydrogen bomb, which stunned everyone by creating a mushroom cloud 100 miles wide and 25 miles high and leaving a mile-wide crater.[64] The US also tested nukes in Nevada near Las Vegas.[65]

in 1946, the first test since World War II[63] and the first of many tests in the Marshall Islands. In 1952, the US detonated its first hydrogen bomb, which stunned everyone by creating a mushroom cloud 100 miles wide and 25 miles high and leaving a mile-wide crater.[64] The US also tested nukes in Nevada near Las Vegas.[65]

As the Cold War progressed, it was defined by the nuclear arms race between the two powers as they invented bigger and bigger weapons and more elaborate ways of delivering them, as well as means of counteracting them.[66][67] In the early stages, the US built up a fleet of B-36s![]() and B-47s,

and B-47s,![]() massive low-flying bombers designed to fly across entire continents to drop nuclear bombs. The Soviet Union responded with the MiG-15,

massive low-flying bombers designed to fly across entire continents to drop nuclear bombs. The Soviet Union responded with the MiG-15,![]() a jet fighter purpose-built for intercepting American strategic aircrafts.[68]:5-6 This, along with other unrelated improvements in Soviet air defenses, prompted the US to develop new high-altitude bombers such as the B-52

a jet fighter purpose-built for intercepting American strategic aircrafts.[68]:5-6 This, along with other unrelated improvements in Soviet air defenses, prompted the US to develop new high-altitude bombers such as the B-52![]() and attempt to refit existing aircraft for high-altitude flights by cutting down on weight.[68]:93,98 Later on, as nuclear warheads got smaller and lighter, so did the delivery systems. Nuclear missiles became more feasible, the US started fielding entire carriers full of aircraft that could carry "tactical" nuclear weapons, and there were brief forays into nuclear artillery (such as the Davy Crockett recoil-less rifle),

and attempt to refit existing aircraft for high-altitude flights by cutting down on weight.[68]:93,98 Later on, as nuclear warheads got smaller and lighter, so did the delivery systems. Nuclear missiles became more feasible, the US started fielding entire carriers full of aircraft that could carry "tactical" nuclear weapons, and there were brief forays into nuclear artillery (such as the Davy Crockett recoil-less rifle),![]() nuclear anti-submarine depth charges (such as Mark 90)

nuclear anti-submarine depth charges (such as Mark 90)![]() and torpedoes (such as the Mark 45,

and torpedoes (such as the Mark 45,![]() sometimes said to have probability of kill of 2, i.e. it destroyed both the sub that it hit and the sub that launched it), and nuclear landmines.

sometimes said to have probability of kill of 2, i.e. it destroyed both the sub that it hit and the sub that launched it), and nuclear landmines.![]() [68]:9-12 The UK, France, and China also developed nuclear weapons.

[68]:9-12 The UK, France, and China also developed nuclear weapons.

In order to ensure collective 'defense' (mutually-assured destruction or "MAD") in the new era of apocalyptic weapons, the US and nations in Western Europe signed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization into existence in 1949.[69] NATO planners projected that holding off a Soviet invasion of western Europe would require a huge army: an estimated 96 divisions worth, in the span of at least a hundred thousand men—men they didn't have. As a result, when Dwight D. Eisenhower became President of the United States, he attempted to compensate for the lack of manpower by encouraging the development of larger warheads, the production and deployment of tactical nuclear weapons, and covert CIA operations against the USSR and its allies.[68]:9

In the late 1940s, the US Army attempted to detect Soviet nuclear tests using highly-sensitive microphones strapped onto chains of balloons floating high in the atmosphere, as part of a top-secret experiment called Project Mogul.![]() One of these balloons crashed near Roswell, New Mexico, and the farmer who discovered the wreckage and the local Army men in the area, neither of whom had any idea of its true, classified purpose, thought it was the remains of a UFO. It was later declared to be a weather balloon, but decades later, in the 1980s, conspiracy theorists brought back the idea that it was actually an alien spacecraft.[70]

One of these balloons crashed near Roswell, New Mexico, and the farmer who discovered the wreckage and the local Army men in the area, neither of whom had any idea of its true, classified purpose, thought it was the remains of a UFO. It was later declared to be a weather balloon, but decades later, in the 1980s, conspiracy theorists brought back the idea that it was actually an alien spacecraft.[70]

The 23-kiloton

"Baker" shot of Operation Crossroads.

"Baker" shot of Operation Crossroads. Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, 1946.

Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, 1946.

The Soviet Union's very first nuclear test, the 22 kt RDS-1,

aka "First Lightning" or "Joe-1". Kazakhstan, 1949.

aka "First Lightning" or "Joe-1". Kazakhstan, 1949.

Operation Hurricane,

a 25-kt explosion and the UK's first nuclear test. Near Australia, 1952.

a 25-kt explosion and the UK's first nuclear test. Near Australia, 1952.

"Ivy Mike", the US's first hydrogen bomb test, a 10.4 megaton

detonation. Eniwetok Atoll, Marshall Islands, 1952.

detonation. Eniwetok Atoll, Marshall Islands, 1952.

US test of a 15-kt warhead for an atomic cannon (!) as part of Operation Upshot-Knothole

Nevada, 1953.

Nevada, 1953.

The 70 kt "Gerboise Bleue",

France's first nuclear test. Near Reggane, Algeria, 1960.

France's first nuclear test. Near Reggane, Algeria, 1960.

The Soviet 50-megaton AN602, a.k.a. Tsar Bomba

Russian Arctic, 1961.

Russian Arctic, 1961.

China's first nuclear test, the 22 kt Project 596 "Miss Qiu",

Lop Nur, China, 1964.

Lop Nur, China, 1964.

The "Loss of China"[edit]

After the war with Japan, the Nationalist and Communist governments of China went back to war with each other. In the new Cold War climate, Mao's communists were given a number of advantages: the Stalinist-backed North Koreans provided supplies and manpower,[71]:110 and the Soviets handed the recently "liberated" Japanese Manchuria over to the communists to act as a base of operations.[72] The inevitable victory by the Chinese communists forced the nationalists into exile on Taiwan and doomed China to decades of brutal dictatorship. It also created a political firestorm in the US.

The "China Lobby" in Congress had attempted to pressure Truman into sending troops into China.[73] These people became harsh critics of Truman after the nationalist loss, saying that Truman was responsible for an "avoidable catastrophe."[74]:55–56

McCarthyism[edit]

The "Loss of China"![]() helped give rise to a wave of anti-communist paranoia in the US, spearheaded by US Senator Joseph McCarthy.[75][76] McCarthy gave speeches claiming that "Communists and queers" had infiltrated the State Department and sabotaged the US' attempts to aid Chiang Kai-shek.[77]:145 These conspiracy theories were further inflamed with the publication of The Shanghai Conspiracy by General Willoughby,[78] a book which claimed that a Soviet-aligned cabal was taking over the US government and had been responsible for Mao's victory.[79]:156

helped give rise to a wave of anti-communist paranoia in the US, spearheaded by US Senator Joseph McCarthy.[75][76] McCarthy gave speeches claiming that "Communists and queers" had infiltrated the State Department and sabotaged the US' attempts to aid Chiang Kai-shek.[77]:145 These conspiracy theories were further inflamed with the publication of The Shanghai Conspiracy by General Willoughby,[78] a book which claimed that a Soviet-aligned cabal was taking over the US government and had been responsible for Mao's victory.[79]:156

McCarthy infamously claimed to have a list of communist spies in the State Department, although he never showed this list to anyone and repeatedly changed his mind as to how many communists were actually on it.[80] The more support he got, the more insane McCarthy became. In 1951, he accused General George C. Marshall of being part of the communist plot.[80] McCarthy's reign of terror continued as he targeted Hollywood, leading to the rise of the Hollywood blacklist[81][82] and bringing Ronald Reagan into the national spotlight as he snitched on fellow actors.[83]

In the end, McCarthy actually damaged US national security. His hysterics led many in the Truman and Eisenhower administrations to dismiss the threat of Soviet espionage when that threat was indeed real, though not in the way that McCarthy had characterized it.[80] That threat along with China's entry into the Korean War fueled a new wave of anti-Chinese sentiment.[84] Instead of doing good work, McCarthy simply chose to focus on wingnut grudges and chasing after innocent and easy targets.

Korean War[edit]

Probably the most significant example of the US commitment to containment policy was the Korean War. Kim Il Sung's North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950 after years of hostility, catching South Korea and the US by surprise.[85]:7-12 Although the invasion was successful for the North, the war quickly turned against them when the UN sent aid.[86] The Soviet Union had boycotted the vote as part of their effort to get a Security Council seat handed from the Republic of China to the People's Republic of China, and as a result, the Security Council had the required unanimous assent for intervention.[87]:16 Sixteen countries sent forces to South Korea, although about 40% of the ground troops were South Korean and 50% were American.[88]:118

The success of the intervention led the US to abandon containment policy. Instead, US forces pushed past the parallel and into North Korea, triggering a Chinese response.[89] With superior Chinese manpower facing the West's troops, the war settled into a brutal stalemate. It ended with an armistice under the watch of newly-elected US president Dwight Eisenhower. North Korea became a totalitarian dictatorship centered around the Kim dynasty[90]:10-11 and South Korea continued as a violent dictatorship under Syngman Rhee.[91]:61-70

During the war, in response to reports of Soviet "truth serums", the United States Navy attempted to find their own truth serums under Project CHATTER,![]() investigating substances such as scopolamine

investigating substances such as scopolamine![]() and mescaline. Around the same time, and possibly continuing long afterwards, the CIA was conducting similar research into using hypnosis and sodium penthothal

and mescaline. Around the same time, and possibly continuing long afterwards, the CIA was conducting similar research into using hypnosis and sodium penthothal![]() in interrogations as of part of Project ARTICHOKE.

in interrogations as of part of Project ARTICHOKE.![]() These experiments paved the way for the infamous MKULTRA.[92]:387-389

These experiments paved the way for the infamous MKULTRA.[92]:387-389

Eisenhower and Khrushchev[edit]

“”Berlin is the testicles of the West. Every time I want to make the West scream, I squeeze on Berlin.

|

| —Nikita Khrushchev to Mao Zedong.[93]:71 |

The new US president Eisenhower moved to reduce the US budget by a third in order to reduce deficits and eventually balance the budget.[30]:194-197 He did this by reducing the US emphasis on ground troops and instead focusing on strategic deterrents like air power and nuclear weapons.

In the Soviet Union, the bellicose Nikita Khrushchev won out over rivals Georgy Malenkov and Vyacheslav Molotov in the power struggle that followed Stalin's death in 1953. Khrushchev shocked the world by delivering a speech in which he exposed and denounced Stalin's crimes.[94][note 3] Although a positive action, it was ultimately a self-serving effort to solidify his personal control over Soviet communism and further remove any remaining Stalin loyalists who would could have threatened him.

Khrushchev also sought to create his own military alliance in opposition to NATO. Curiously, though, this plan began with a Soviet government application to join the NATO alliance in 1954. The Soviets never expected to be accepted, and the proposal was simply meant to give urgency to the creation of a communist military bloc upon its rejection.[96] The NATO members actually considered allowing the Soviets to become an ally, but ultimately rejected the proposal since NATO didn't accept non-democratic nations.[97]

Immediately following NATO's answer, the Soviets declared the alliance illegitimate since it was obviously targeted against them and ideologically biased. In 1955, Khrushchev went ahead and created his communist military alliance, the Warsaw Pact, largely in response to the creation and rearmament of West Germany.[98]

Hungarian Revolution[edit]

“”The wound which the Hungarian Revolution inflicted on communism can never be completely healed.

|

| —Milovan Đilas, Yugoslav politician.[99]:196 |

As part of his program of de-Stalinization, Khrushchev removed Mátyás Rákosi,![]() the Stalinist[100][101] leader of Hungary.[102] This encouraged liberals in Hungary to begin pushing for more civil rights and freedom.[103] Popular discontent against communism and the ongoing Russian occupation led to mass protests. In November of 1956, however, the Soviet Union rallied its forces and attacked its own ally, killing 3,000 Hungarian civilians in a rapid and brutal invasion.[104] Many thousands of Hungarians were kidnapped and taken to the Soviet Union,[105] about 200,000 Hungarians fled to Austria,[106] and Hungarian leader Imre Nagy and his allies were executed.[107][108]

the Stalinist[100][101] leader of Hungary.[102] This encouraged liberals in Hungary to begin pushing for more civil rights and freedom.[103] Popular discontent against communism and the ongoing Russian occupation led to mass protests. In November of 1956, however, the Soviet Union rallied its forces and attacked its own ally, killing 3,000 Hungarian civilians in a rapid and brutal invasion.[104] Many thousands of Hungarians were kidnapped and taken to the Soviet Union,[105] about 200,000 Hungarians fled to Austria,[106] and Hungarian leader Imre Nagy and his allies were executed.[107][108]

The brutal Soviet repression of the Hungarian Revolution had a catastrophic impact on the communist world. Many communist countries were disillusioned with their own cause, the West was infuriated, and communist parties abroad saw great declines in membership.[99]:196 In contrast, some communists actually defended the USSR's actions, and some still do now. These people are often referred to as "tankies", after the tanks the Soviet Union sent to subjugate the Hungarians.

Soviet split with China and Albania[edit]

Although the Soviets faced criticism for being too brutal, they also ended up losing their most valuable ally for not being brutal enough. The split began when Khrushchev denounced Stalin and his policies, as Mao had been fond of Stalin and his methods.[93]:142 Mao turned around and denounced Khrushchev as having lost his revolutionary edge. China and the Soviet Union began competing against each other for influence over communist nations.[109] The conflict hit its worst point when the Soviets publicly supported the 1959 Tibet uprising and then Khrushchev and Mao had a screaming match during a diplomatic meeting in Romania.[110] The Soviets broke off relations with China and withdrew their technical advisors, leaving the process of Chinese modernization unaided. These events fractured the previously united communist bloc and had critical ramifications for the later American intervention in Vietnam.

The split from China also helped cause the Soviet Union to lose another ally in Albania. Enver Hoxha, the dictator of communist Albania, had adopted a policy of sucking up to Stalin by defending and promoting the ex-Soviet leader's brutal methods of leadership. As a result, the Stalin spent the last years of his life investing heavily in the impoverished Balkan nation, greatly improving its healthcare and education systems.[111] When Khrushchev came to power and began denouncing Stalinist dogmatism, Hoxha and the Albanian prime minister Mehmet Shehu both considered this to be a serious threat to their power.[111] By 1960, Albania was openly defying the Soviet line by refusing to denounce China, and Khrushchev's government retaliated by refusing Albania's emergency request for grain shipments to alleviate an ongoing food crisis.[112] Chinese leaders quickly stepped in to fill the gap by providing the needed grain and industrial assistance, thus turning Albania into their faraway proxy and a thorn in the Iron Curtain.[112] By 1961, the split was complete. The Soviets had severed trade, expelled Albanian students from its universities, and withdrew its military assets from Albania's territory.[112]

Beginning of the Space Race[edit]

“”Our movies and television programs in the fifties were full of the idea of going into space. What came as a surprise was that it was the Soviet Union that launched the first satellite.

|

| —John Logsdon, Director, of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University.[113] |

The nuclear arms race continued to escalate throughout the late 1950s as both superpowers began to build weapons with the explicit purpose of reaching each other's territories.[114] In 1957, the Soviet Union built and tested the world's first Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, the R-7 Semyorka.![]() [115][116] In October of the same year, the Soviets launched the first human-made satellite into orbit, the Sputnik 1.[117]

[115][116] In October of the same year, the Soviets launched the first human-made satellite into orbit, the Sputnik 1.[117]

This naturally scared the fuck out of the American government, not only because the Soviets were getting the edge on nuclear weapons delivery systems, leading to perception of a "missile gap" and "bomber gap",[68]:14-15 but also because the Soviets were apparently very good at educating scientists (despite ideological setbacks) while the US education system was still churning out a bunch of racist rubes. In fall of 1958, Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act,![]() which provided about a billion dollars in funding for US education at all levels.[118][119] This began the US commitment to improving STEM education and racing with the Soviets to develop space-faring technology.

which provided about a billion dollars in funding for US education at all levels.[118][119] This began the US commitment to improving STEM education and racing with the Soviets to develop space-faring technology.

Even then, it took a bit for the US to catch up. In 1957, Sputnik 2 launched Laika the space dog into orbit, where she became the first animal to orbit the planet.[120][121] In 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to reach space and to orbit the Earth.[122] Alan Shepard got there about a month later and became the first American in space.[123] Not as impressive a title. but some might argue he pulled off the first 'completed spaceflight' under the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) Sporting Code (Section 8, paragraph 2.15, item b), which nitpicks that a flight’s incomplete if 'any member of the crew definitively leaves the spacecraft during flight.' Gagarin and the Vostok gang bailed out mid-descent, so their missions technically flopped by that standard. Shepard’s suborbital jaunt, though? It stuck the landing—literally and figuratively. Still, calling it the 'first completed spaceflight' feels like handing out a participation trophy when the Soviets were already lapping the track."[124][125]

Either way, the Americans did at least manage to snag the title of first meal in space the next year when, during the flight of the Friendship 7,![]() John Glenn dined on some sugar tablets with water and a tubeful of applesauce.[126] Yummy.

John Glenn dined on some sugar tablets with water and a tubeful of applesauce.[126] Yummy.

| Who | Event (mission) | Year |

|---|---|---|

| first interncontinental ballistic missile |

1957 | |

| first artificial satellite (Sputnik 1 |

1957 | |

| first animal in orbit, Laika |

1957 | |

| first human spaceflight, Yuri Gagarin (Vostok 1 |

1961 | |

| first woman and first civilian in space, Valentina Tereshkova |

1963 | |

| first spacewalk |

1965 | |

| first lunar landing and lunar surface photos (Luna 9 |

1966 | |

| first lunar human flyby (Apollo 8 |

1968 | |

| first humans on the moon (Apollo 11 |

1969 | |

| first landing on another planet, Venus (Venera 7 |

1970 |

Escalation[edit]

The Berlin Wall[edit]

In November 1958, Khrushchev made an unsuccessful attempt to turn all of Berlin into an independent, demilitarized "free city" by delivering a six-month ultimatum to the western powers to withdraw their troops from the sectors they still occupied in West Berlin or face a renewed Berlin blockade.[127] This effort failed, and it put more light on the ongoing West Berlin problem. Around 2.7 million people left the GDR and East Berlin between 1949 and 1961, many of whom were valuable working age people.[128] In 1961, East Germany closed its border with West Germany and West Berlin. The GDR's Council of Ministers announced that "in order to put a stop to the hostile activity of West Germany’s and West Berlin’s revanchist and militaristic forces, border controls of the kind generally found in every sovereign state will be set up at the border of the German Democratic Republic, including the border to the western sectors of Greater Berlin."[128] This heralded the construction of the Berlin Wall, an infamous symbol of communist tyranny.

US and Soviet relations soured further when the U-2 spy plane scandal![]() broke out in 1960. The Soviets had shot down a US spy plane and then President Eisenhower was embarrassingly caught in a lie when the USSR disproved his denials by parading the captured pilot in front of international news cameras.[129][130] The aftermath of this incident prompted the CIA to create a plane that could outrun the missiles that shot down the U-2, leading to the development of the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird

broke out in 1960. The Soviets had shot down a US spy plane and then President Eisenhower was embarrassingly caught in a lie when the USSR disproved his denials by parading the captured pilot in front of international news cameras.[129][130] The aftermath of this incident prompted the CIA to create a plane that could outrun the missiles that shot down the U-2, leading to the development of the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird![]() [131] The flight tests for the SR-71 took place at Area 51; it is thought that some of the UFOs supposedly spotted there were there were actually sightings of the SR-71 and other experimental aircraft. The incident also caused US nuclear strategy to shift from high-altitude bombers to low-flying craft that could ideally escape radar detection.[68]:13-14

[131] The flight tests for the SR-71 took place at Area 51; it is thought that some of the UFOs supposedly spotted there were there were actually sightings of the SR-71 and other experimental aircraft. The incident also caused US nuclear strategy to shift from high-altitude bombers to low-flying craft that could ideally escape radar detection.[68]:13-14

Shenanigans in the Third World[edit]

Communism also became a major force in the Third World during the era of decolonization. This was only to be expected given communism's anti-colonial stance as well as the fact that France and the British Empire were US and capitalist-aligned allies. The US feared that the Soviets could effectively get most of Africa and Asia on a silver platter as the newly-freed nations turned to them for protection. This influenced Eisenhower's decision making in the Suez Crisis; he publicly sided with Egypt over the UK and France as a means of demonstrating that the US was an anti-colonialist nation as well.[132] This benevolence would not continue in future administrations, or even Ike's own.

Under Ike's watch, the US helped overthrow the democratically-elected government of Iran at the request of the British in retaliation for their nationalization of Iran's oil reserves.[133]:775 This doomed Iran to decades of despotism under an absolute monarch. In 1954, the CIA launched a coup against the democratically-elected government of Guatemala, beginning four decades of civil war, dictatorship, and genocide in that country.[134][135]

President John F. Kennedy deepened US involvement in Indochina, which later had catastrophic results in the ever-expanding Vietnam War. The Johnson administration sponsored a 1964 military coup in Brazil.[136] In 1966, the US aided Indonesian dictator Suharto in mass murdering over 500,000 people.[137] The US also helped bring the brutal dictator Augusto Pinochet to power in Chile by sponsoring his coup against the legitimate government of Salvador Allende.

These events and others are a big part of why the US is not well-liked in the Third World today.

Bay of Pigs invasion[edit]

Communists led by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara seized power in Cuba during the 1959 Cuban Revolution, having benefited from the fact that the Eisenhower administration had refused to lend aid to the unpopular and despotic Batista regime.[138]:23–24 While Ike might not have liked Batista, Ike didn't like Castro any better. The president refused to meet Castro in Washington DC, and he left Vice President Richard Nixon to do the unpleasant business in his place.[139]:142 This was the beginning of a long period of hostility between Cuba and the US, culminating in various assassination attempts on Castro, under the Kennedy administration. The United States also "encouraged terrorism in the hope of provoking indiscriminate violence and repression, in order to weaken government legitimacy and attract new converts to armed struggle"[140]:127 in Cuba, another reason why America's stance on "Freedom and Democracy" is all the more hypocritical.

At the very end of Eisenhower's presidency, he allowed the CIA to explore options for removing Castro from power and granted them a budget with which to achieve this aim.[141] Kennedy approved the plan in 1961 after becoming president. The CIA had organized an invasion force out of Cuban exiles and trained them in Guatemala; and then they sent the invasion force to launch a naval attack on Cuba.[142] Just about every part of the plan that could possibly have gone wrong went wrong, and Kennedy abandoned the cause and refused to provide the invasion force with promised air support.[143] The result was a humiliating loss for the US that turned Castro into a national hero and permanently poisoned US-Cuba relations.

Cuban Missile Crisis[edit]

The failed invasion also pushed Castro into allying formally with the Soviet Union, and the Soviets pledged themselves to Cuba's defense.[144]:95 To this end, the Soviet Union moved a bunch of medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Cuba, the kind that could hit the US with a nuclear warhead within minutes,[145] telling the native Cubans that the soldiers sent to guard them were "agricultural specialists".[146] Kennedy was not thrilled with this idea.

In October of 1962, Kennedy met with his advisers and weighed three possible options: 1) do nothing, 2) blockade Cuba (an act of war), or 3) launch a military strike.[146] Kennedy thankfully ruled out the military option, since there was no guarantee that all missiles would be neutralized before the Soviets could retaliate. Instead, Kennedy went with the second option, but chose to call the blockade a "quarantine" in an attempt to avoid outright war.[146] He then ordered the US Strategic Air Command to DEFCON 2 (the step preceding nuclear war) and ensured that 66 B-52s carrying hydrogen bombs were constantly airborne and replaced with a fresh crew every 24 hours.[146]

Perhaps the most dangerous moment of the entire Cold War came on October 27th, when the US navy fired warning shots at a Soviet submarine that had lost contact with Moscow and was thus unaware of the situation. The boat was convinced that the Americans had declared war and attacked them, and only the dissent of Second Captain Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov stopped them from launching a nuclear missile.[146] In the end, the conflict was resolved when Khrushchev sent a private letter to Kennedy offering a peaceful resolution. The two leaders agreed that the US would promise not to ever attack Cuba again and (secretly) withdraw its Jupiter ICBMs from Turkey (which were a similar proximity threat to Russia as Cuban missiles were to the US) in exchange for the Soviets pulling their missiles out of Cuba.[146]

The terror of the Cuban Missile Crisis convinced the US and the USSR to sign the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which banned the testing of nuclear weapons unless conducted belowground.[147] The crisis also triggered the political downfall of Nikita Khrushchev.[93]:119

Vietnam War[edit]

Among the US' mistakes in the Third World was a long series of fuckups that helped railroad it into the quagmire in Vietnam. Beginning with the Truman administration, the US backed France's attempts to reassert colonial rule in Indochina.[148] Why? So the goddamn communists wouldn't win, of course! This was despite the fact that Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh had an undisguised admiration and friendliness towards the United States.[149] Ho had stressed to President Woodrow Wilson that he was a nationalist first and a communist second and would have been perfectly happy cooperating with the United States.[150]

The French loss in Indochina led to the 1954 Geneva Conference, which partitioned Vietnam and created new states in Indochina. Elections were supposed to be held in 1956 to peacefully reunite the country and end the violent struggle between Vietnamese communists and anti-communists.[151] The US did not allow this to happen. Instead, the US began a program of sabotage against Ho's North Vietnam while propping up a capitalist dictator in South Vietnam,[152] and goddamn does this story sound depressingly familiar. The decisions made by the Eisenhower administration regarding Vietnam at this point were made against the advice of the American intelligence community, who viewed the effort to prop up South Vietnam indefinitely as wasteful and foolhardy.[152] Kennedy escalated US involvement by increasing the number of US troops ("advisors") in the region.[153]

It was President Johnson who finally declared a full war in the region by sending huge numbers of US troops there. The ensuing conflict was an ungodly quagmire that killed numerous people on both sides and spurred opposition at home. The US' losing war in Vietnam likely represented the lowest point of its involvement in the Cold War; national unity had never been lower and its prestige and finances took some serious blows.

Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia[edit]

“”It is a sad commentary on the communist mind that a sign of liberty in Czechoslovakia is deemed a fundamental threat to the security of the Soviet system.

|

| —US president Lyndon Johnson.[154] Hypocritical? Yes. Also correct? Oh, yes. |

In 1968, elections in communist Czechoslovakia brought communist politician Alexander Dubček to power. This marked the beginning of the "Prague Spring," a period that refers to the Dubček government's attempts to liberalize Czechoslovakia, reform its economy, and grant more liberties to its citizens. These reforms were outlined in the "Action Programme", and this document promised an end to arbitrary arrests, more freedom of speech, more equal representation for Slovakia, and increased freedom of action for Czechoslovakia's industries. The Soviet Union did not like this idea.[155]

In response to the developments in Czechoslovakia, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev launched a massive invasion of Czechoslovakia backed by his puppets in the Eastern Bloc. Just like with Hungary, the invasion was conducted with great speed and most civilians simply went along with it out of fear, despite having supported the liberalizing reforms.[156] Czechoslovakia's liberal politicians were jailed, including Alexander Dubček. The new Czechoslovak government purged liberals from its ranks and quickly rolled back Dubček's reforms.[157]:100-101

To justify the invasion, the Soviet Union subsequently adopted the "Brezhnev Doctrine," which stated the any threat to communism in an Eastern Bloc state was a threat to all communist nations. Therefore, the Soviet Union would reserve the right to violate the sovereignty of any communist country that attempted to replace communism with capitalism.[158] The Brezhnev Doctrine would later be invoked in the Soviet-Afghanistan war. The Brezhnev Doctrine was also illegal under Article 2, Chapter 4 of the United Nations Charter, not that the Soviets or any other significant country really gave a shit.

Détente[edit]

Apollo 11 moon landing[edit]

Although president Kennedy had framed the Space Race as a means of boldly going where no man has gone before, it was in reality conducted with coldly political objectives in mind on both sides. During the Sixties, as the Soviets and the Americans began to take seriously the idea of going to the Moon, and this ushered in the era of either blowing up dogs and monkeys or shooting them into the cold vacuum of space to die. Poor Laika. During the Sixties, it seemed like the Soviets were pulling ahead, as they managed to put the first woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova), and had a Soviet cosmonaut conduct the first-ever spacewalk (Alexei Leonov), and then had two Soviet cosmonauts conduct the first ever space rendezvous (Andrian Nikolayev and Pavel Popovich).[159] In 1967, tragedy struck for the Americans when the first Apollo crew died due to an accidental fire in their training capsule.[159] The Soviets also lost a cosmonaut in the same year when his spacecraft's parachute failed and slammed into the ground.

After closing down for about a year, NASA then reopened in 1968 and hurriedly tried to catch up to the Soviets. Soviet propaganda was convincing the world that they were on the verge of doing a moon landing, although this was in reality nowhere near true.[159] In the end, US astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first man on the moon, landing there with Buzz Aldrin in 1969.[160] There were a number of reasons why the US finally managed to pull ahead. Soviet scientists worked under harsh conditions and constant fear of punishment, while NASA encouraged questions and candid reports.[159] Soviet resources were more limited than what the Americans had, and they then divided their resources into pursuing the competing aims of two rival scientists.[159] And finally, the US had far more sophisticated electronics and computers.[159]

It's debatable to what extent the moon landing actually influenced the Cold War. Roger Launius, NASA’s former chief historian, argued that the moon landing increased US prestige and helped them gain allies in the latter half of the Cold War.[161] Other historians argue that the Soviets took Ronald Reagan's much-ridiculed "Star Wars" program very seriously because of the US' previous moon landing success, leading them to spend huge amounts of money in an attempt to counter it and speeding their own downfall.[162]

Soviet stagnation[edit]

The Brezhnev years are sometimes called the "Era of Stagnation" due to the fact that the 1970s and 1980s were a dismal time for the Soviet economy. This happened for a variety of reasons, and many are debatable. The first was that the numbers of working-age people in the Soviet economy started to decrease due to declining birthrates and increasing mortality rates.[163] Mounting economic problems also seem to have had a negative impact on worker enthusiasm and productivity across the Soviet Union.[164]:416 These problems were also likely heightened by Brezhnev's increases in political repression and the unresponsive nature of his government. The Brezhnev government also seemed to have struggled to manage the increasingly large and complex Soviet economy, but it still refused to engage in any significant liberalization.[163]

Later, the oil crisis of 1973 shocked the economies of communist Europe, and the economies took longer to recover than the US.[165]:44-45 Other contributing factors seem to have included Soviet resistance to economic globalization.[165]:28

Stagnation had a greatly negative impact on living standards in the Soviet Union. The economic slump combined with the Soviet Union's lack of concern for consumer goods meant shortages and long waiting periods for things that Americans took for granted like automobiles, televisions, refrigerators, and washing machines while simpler consumer items like clothing and footwear were derided for their low quality.[166] This later became a political liability as later US president Ronald Reagan would gleefully mock the poor economic conditions endured by Soviet citizens.

Although the causes are still unclear, it's undebatable that the Soviet era of stagnation contributed to its eventual downfall.

Nixon goes to China[edit]

“”Only Nixon could go to China.

|

| —Old Vulcan proverb.[167] |

Tensions between the Soviets and China peaked in 1969, and the two nations even fought an undeclared war with each other in Manchuria that may have killed hundreds of people.[168] In 1971, US president Richard Nixon stunned the world by announcing that he had been holding secret talks with the Chinese government and was now ready to meet with Chinese leaders in Beijing.[169] Nixon's visit had two motivations. The first was the wise realization that "there is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation".[169] The second was the realization that the US could potentially ask China to pressure its North Vietnamese allies into negotiating a way out of the still-ongoing Vietnam War for the US.[169]

All of this diplomacy culminated in Nixon's historic 1972 visit to Communist China in which he held a week-long summit with their leaders. This visit paved the way for full normalization of relations between the US and China, and it also cemented US policy towards Taiwan as "we technically don't recognize their independence."[170] The visit also helped convince the Soviets to accept a thawing of Cold War tensions.

Nixon goes to Moscow[edit]

Later in 1972, Nixon met with Soviet leaders in a historic visit to Moscow. It was the first time in history a US president had visited Moscow, and Nixon met with Brezhnev to discuss reapproachment and cooperation between the two superpowers.[171] This quest for common ground culminated in the important Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, a series of bilateral conferences that resulted in two nuclear arms control treaties. The two leaders also sought to increase economic ties between their nations, especially sought-after by Brezhnev, who needed to bolster the stagnating Soviet economy.[30]:194-197 East and West cooperated once more in signing the Helsinki Accords, a non-binding agreement to be a bit nicer to each other.[172]

Communist infighting in Asia[edit]

After the wars in Indochina, Pol Pot, one of the evilest dictators in history, came to power in Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge, which had previously been influenced by communist Vietnam, then rapidly began distancing themselves, and Vietnam later admitted to the Soviets that they had zero control over what was happening in Cambodia.[173] It was around this time that Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge committed the horrifying Cambodian genocide, murdering between 1.5 and 2 million people in their insane quest to transform Cambodia into a tranquil agrarian utopia.[174]

Tensions rose between Cambodia and Vietnam due to a combination of territorial disputes and disagreement over which country should be the primary leader of communism in Southeast Asia. This culminated with Cambodia's 1978 invasion of Vietnam, and Cambodian troops exterminating any Vietnamese civilians that they found.[175] Among these atrocities was the Ba Chuc massacre, where Khmer Rouge forces murdered about 3,000 civilians, with one survivor remembering, "They shot my children dead one by one. My youngest, a two-year-old girl, was beaten three times but did not die, so they slammed her against a wall until she was dead."[176] The war was conducted brutally, and an estimated 30,000 Vietnamese soldiers died.[177] Thankfully, the Vietnamese emerged victorious.

China, however, had been a supporter of Pol Pot's vile regime, and they launched a punitive invasion of northern Vietnam that killed tens of thousands of people and ended inconclusively.[178] This conflict ended up being a blow to Soviet prestige, as the Chinese conclusively demonstrated that the Russian superpower was unable to protect their Vietnamese allies.[179]:297

Iranian Revolution[edit]

The US and the Soviets also generally agreed that the 1979 Iranian Revolution was a bad thing. The revolution likely became inevitable due to the US' assistance in making the Shah an absolute monarch who despotically mismanaged Iran. Tension erupted into mass protests and insurrection, and Ayatollah Khomeini became a leading figure of the anti-Shah forces. He called for an Islamist state, and this emphasis on religious law naturally put him into conflict with the Soviets. In September of 1979, the Soviet Union officially denounced the Iranian Revolution, calling it a disaster for Iran that only brought economic chaos, political persecution and repression of minorities.[180] When Khomeni's regime started cracking down on Iranian communists and expelling Soviet diplomats, the Soviets became their enemy.[181] They would later join the US in aiding Iraq against Iran in the 1980 Iran-Iraq War.

The Revolution had a far-reaching ripple effect, and it likely helped end the period of détente. The turbulence it caused and the US' loss of a major regional ally emboldened the Soviets to invade Afghanistan.

Extreme tensions[edit]

Soviet-Afghanistan War[edit]

“”For us, the idea was not to get involved more than necessary in the fight against the Russians, which was the business of the Americans, but rather to show our solidarity with our Islamist brothers.

|

| —Osama bin Laden on the war against the Soviets.[182] |

The détente period decisively and immediately ended due to the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan.

In 1978, the communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan seized power in a coup[183][184] and reestablished Afghanistan as a "Democratic" Republic.[185] Once in control, the party implemented socialist policies, most notably land reform. This greatly pissed off the Afghan people, since property was confiscated haphazardly, causing agricultural production to fall and the economy to go down the shitter.[186]:115-116 On the plus side, the communists granted legal equality to women and established the Afghan Women's Council to improve their lot.[187]:222-228 This progressive step turned hardcore Islamists against the government. Unfortunately, there were lots of those.

The situation unsurprisingly exploded into a guerrilla conflict later in 1978, with the Islamist mujaheddin receiving aid from Pakistan and China.[188] In September 1979, Afghan president Nur Muhammad Taraki was assassinated by his political rival Hafizullah Amin, who was then assassinated by the Soviet Union in retaliation.[189]:25-28 In the chaotic wake of the assassinations, the Soviets sent about 100,000 troops into Afghanistan to "stabilize" the region.[190]:40-41

Soviet interventionism was immediately condemned by Afghanistan's fellow Islamic-majority nations. US President Jimmy Carter retaliated by withdrawing from the arms limitation treaties and then boycotting the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics.[93]:211 The Carter administration and even more than the incoming Reagan administration made it a policy to financially and materially support the mujaheddin insurgency against the Soviets.[191] This decision if anything exacerbated the problem (9/11, Afghanistan War). The mujaheddin managed to kill about 14,000 Soviet soldiers with US help, and the whole affair became a quagmire that sapped the Soviet Union's already stagnating economy.[192] For this reason, the war is often glibly referred to as "the Soviets' Vietnam."[30]:314

Reagan Doctrine[edit]

“”My idea of American policy toward the Soviet Union is simple, and some would say simplistic. It is this: We win and they lose. What do you think of that?

|

| —US President Ronald Reagan.[193] |

“”In the Soviet Union the fear that the West was about to unleash a 'hot' war was growing. The installation of the Reagan regime and its inflammatory rhetoric had so concerned the Soviets that at a session of the KGB high command and senior staff, General Secretary Leonid Brezhnez and KGB chief Yuri Andropov stated that the United States was actively preparing for a nuclear attack on the USSR.

|

| —John Clearwater, nuclear weapons historian.[194]:8 |

Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter in the 1980 election, among other things promising to increase military spending and attempt to defeat communism worldwide.[93]:189 He was joined in this aim by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. His war against the Soviet Union began quickly. In 1982, he blocked the construction of a gas pipeline from the Soviet Union to Europe, hurting their economy but also annoying America's allies.[195] Along with supporting insurgents in Afghanistan, Reagan sent the CIA to increase support for radical Islamism in the Central Asian Soviet republics.[196] This policy also called for helping Pakistan to train and radicalize Muslims globally for the purpose of conducting a global jihad against the Soviet Union. And that policy caused no complications later on.

After the 1984 U.S. presidential election,![]() Reagan formalized his so-called "Reagan Doctrine". It called for the US to support any and all anti-communist movements around the world — this was unsurprising since Reagan had supported McCarthyism in the 1950s.[83] For the first time, the US sought not to survive the Cold War, but instead to win it.

Reagan formalized his so-called "Reagan Doctrine". It called for the US to support any and all anti-communist movements around the world — this was unsurprising since Reagan had supported McCarthyism in the 1950s.[83] For the first time, the US sought not to survive the Cold War, but instead to win it.

Polish Solidarity movement[edit]

In 1980, disgruntled members of the Polish public founded the Independent Self-governing Labour Union "Solidarity" (Solidarność) to push for more worker's rights and political freedoms by using civil disobedience.[197]:127-143[198] The movement received significant financial support from the United States.[199]:589

Poland had long been a troublesome satellite state for the Soviet Union due to its long history of conflict with Russia, tradition of personal freedom, and strongly religious culture.[200] As a result, the communists' rule in Poland was looser and more flexible. Polish political society began rising after Polish archbishop Karol Wojtyla was elected Pope, becoming Pope John Paul II.[200] His visit to Poland drew crowds of millions and reawakened Polish national identity. This impetus fueled Solidarity, and by 1980 it had about 10 million members.[200]

Fearing the political movement, Poland's communist authorities put the country under martial law for almost two years. Once again, a Soviet satellite had tanks rolling through its streets, although this time they weren't owned by the Red Army. There was a reason for this. The Soviet Union was afraid of invading Poland, as their economy had become fragile enough to make any potential sanctions imposed by the West a real threat to their nation's stability.[93]:219-222 The Polish crackdown led to thousands of arrests and killed 91 people.[201]

Renewed arms race[edit]

Part of Reagan's strategy involved an intensified arms race against the Soviet Union. One of his proposals was the Strategic Defense Initiative, nicknamed "Star Wars", which he claimed could protect the US from an intercontinental ballistic missile launch. Despite this failure, it successfully incited the Soviets into greater levels of spending to counter it, as the shock of losing the Space Race had convinced them to take America's batshit claims seriously.[202]

In his first term and beyond, Reagan increased the size of the US military. It was, in fact, the largest peacetime military buildup in United States history.[203]:6 In 1983, the US increased tensions even further by deploying 108 Pershing II![]() ballistic missiles to West Germany,[204][205][206][207] which sparked protests across Europe.[208][209][210] This almost resulted in nuclear war. The tense situation in Europe put the Soviets on a hair-trigger, and in 1983, an equipment malfunction almost convinced them that the US was launching missiles.[211] In November of that year, some extremely realistic military exercises by NATO fooled the Soviets into believing that eastern Europe was about to be invaded, and they responded by placing their nuclear forces on alert and readying their air forces in East Germany and Poland.[212][204]

ballistic missiles to West Germany,[204][205][206][207] which sparked protests across Europe.[208][209][210] This almost resulted in nuclear war. The tense situation in Europe put the Soviets on a hair-trigger, and in 1983, an equipment malfunction almost convinced them that the US was launching missiles.[211] In November of that year, some extremely realistic military exercises by NATO fooled the Soviets into believing that eastern Europe was about to be invaded, and they responded by placing their nuclear forces on alert and readying their air forces in East Germany and Poland.[212][204]

In terms of weakening the Soviet empire, however, the arms race was a success. By the 1980s, the Soviets were throwing about 25% of their GDP into the military, neglecting their domestic civilian economy as a result.[30]:332 Soviet spending on the arms race exacerbated their internal weaknesses and worsened their natural economic slump. This also coincided with the post-OPEC-crisis surplus in the global crude supply that both benefited the US economy and grievously harmed the Soviet economy, which had become dependent on oil exports.

Korean Air Lines Flight 007[edit]

The high-stakes standoff between superpowers caused actual deaths in September 1983 when a passenger jet flying from New York City to Seoul apparently strayed into Soviet airspace and was shot down by paranoid Soviet defense forces.[213] The Soviets claimed that their jet tried to fire warning shots, but this was either untrue or else the jet was using non-tracer shots that would have been invisible at night.[214]

The event was especially jarring because one of the passengers was Representative Larry McDonald,![]() a conservative Democrat and kook ([215][216] from Georgia's 7th District, and the second president of the John Birch Society.[217] Soviet leader Yuri Andropov accused the US of deliberately placing the civilian plane in the line of fire, while conspiracy theories in the US circulated claiming that the Soviets had actually kidnapped McDonald and the other passengers.[218] The event, along with the two nuclear close-calls, helped make 1983 one of the worst years of the Cold War.

a conservative Democrat and kook ([215][216] from Georgia's 7th District, and the second president of the John Birch Society.[217] Soviet leader Yuri Andropov accused the US of deliberately placing the civilian plane in the line of fire, while conspiracy theories in the US circulated claiming that the Soviets had actually kidnapped McDonald and the other passengers.[218] The event, along with the two nuclear close-calls, helped make 1983 one of the worst years of the Cold War.

US invasion of Grenada[edit]

“”Why are we invading Spain?

|

| —US staff officer upon receiving orders to head to Grenada.[note 4][219] |

The United States invaded the Caribbean island nation of Grenada in October 1983, and this was one of the few US foreign interventions that actually worked out. First, some context. Grenada gained independence from the UK in 1974, but the Marxist-Leninist New Jewel Movement took power in 1979 and turned the island into a dictatorship.[220] The US wasn't happy about having a communist island nation so close to their old enemy Cuba. In 1983, political unrest resulted in the murder and replacement of the island's communist dictator with a different communist dictator, and the US used this as a convenient excuse to invade.[221] The UK and Canada objected to the attack because they had actually invested in the construction of an airport in Grenada. The US invaded anyway.

On November 2nd, 1983, the United Nations General Assembly, by a vote of 108 to 9,[222] declared the military action "a flagrant violation of international law."[223] The US didn't really give a shit, because why would they? Despite the international backlash, the invasion was a rapid success. This was a major political win for Reagan, as he was able to point to it as a sign that his "rollback" strategy against communism was working (never mind that the country's population was <100,000).[224] The US made Grenada into a democracy, and to this day the island nation celebrates the day of the invasion as Thanksgiving.[225]

Iran-Contra scandal[edit]

Reagan's aggressively anti-communist foreign policy led to a very serious overstep of his presidential power.

In 1979, the Sandinista National Liberation Front overthrew the Somoza dictatorship and aligned themselves with the Soviet Union and Cuba, although they never adopted a Soviet-style command economy.[226][227] This made Reagan angry. The Sandanistas immediately came into conflict with the counterrevolutionary Contras, and the CIA naturally started training and supplying Contra fighters.[228]

During their struggle against the Sandanista government, the Contras were responsible for some sickening atrocities. In 1985, Newsweek described how Contras would execute their victims, saying: "The victim dug his own grave, scooping the dirt out with his hands… He crossed himself. Then a contra executioner knelt and rammed a k-bar knife into his throat. A second enforcer stabbed at his jugular, then his abdomen. When the corpse was finally still, the contras threw dirt over the shallow grave — and walked away."[229]:268 Contra leader Edgar Chamorro was quite candid about the fact that the Contras would routinely murder civilians but attempted to justify it all by saying to a US reporter, "Sometimes terror is very productive. This is the policy, to keep putting pressure until the people cry 'uncle'".[230]:309 It's worth noting at this point that Reagan called the Contras, "the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers."[231]

Fully aware of the atrocities being committed by the Contras, Congress twice forbade Reagan from sending aid to them, first in 1982 and then in 1984.[232]To circumvent the Congressional ban, US National Security Council member Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North secretly devised and implemented a plan by which the US would sell weapons to Iran in exchange for Iranian assistance in freeing US hostages held by Hezbollah, and then the Reagan administration would use the proceeds to covertly aid the Contras.[232] In other words, the Reagan administration armed one of the US' most intractable enemies so that they could arm some brutal death squads in Central America. The scandal was exposed when the Sandinistas shot down a plane full of CIA-bought guns.[233]

In the end, Oliver North was sentenced to prison time, but later had the sentence vacated by an appeals court.[232] Like any good loyal attack dog, North took the fall for his boss by illegally destroying White House documents in order to prevent anyone from knowing how involved Reagan really was in the affair.[232] North later got a nice cushy job as the president of the National Rifle Association, and later as board member.

Able Archer 83, the nuclear scare that changed everything[edit]

By the fall of 1983, US-Soviet relations were at the worst point since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Soviet leader Yuri Andropov was concerned about an American first-strike with nuclear weapons, writing in 1981 that "The main objective of our intelligence service is not to miss the military preparations of the enemy … for a nuclear strike".[234] The Reagan administration, on the other hand, assumed that Soviet leadership understood that the United States would never do such a thing and were merely highlighting their fears to convince Reagan to slow the US arms buildup.[235] In other words, the Soviets genuinely believed the US wasn't bluffing about nuclear war, while the US was convinced that the Soviets were bluffing about not believing that the US was bluffing.

This was the context in which NATO held Operation Able Archer, a massive and completely realistic military exercise. Held between 7 and 11 November 1983, Able Archer featured dummy warheads, DEFCON status changes, and periods of radio-silence that, combined with the other elements of the exercise, terrified Soviet intelligence.[235] The Soviets were aware that Able Archer wasn't much different from a genuine military coordination and could therefore actually be one. In response, the Soviet air force began preparations for the immediate use of nuclear weapons (actually loading some) and conducted an unprecedented 36 surveillance flights.[235]

It was only after Able Archer concluded that it dawned on Western leaders how close the Soviets had come to launching a nuclear attack. Margaret Thatcher was horrified and immediately petitioned the US not to conduct such a realistic exercise ever again.[236] Reagan himself was shaken, calling a CIA report on Soviet war preparations "really scary".[235] On 18 November, he wrote in his diary that, "I feel the Soviets are so defense minded, so paranoid about being attacked that without in any way being soft on them we ought to tell then no one here has any intention of doing anything like that."[235]