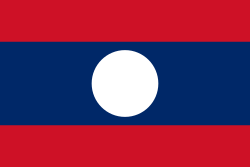

Laos

“”Beyond the smiles and the easy-going pace of Laos that attracts the tourists, the Lao government is still a very secretive, authoritarian state that tolerates no challenges, real or perceived, to its authority. There is a high intimidation factor, because the Lao government also doesn’t clearly mark where the political red lines are that will prompt them to act, so self-censorship in words and actions is increasingly the norm.

|

| —Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director with the Human Rights Watch.[1] |

The Lao People's Democratic Republic, officially called Laos, is neither democratic nor for the people. Instead, it is a Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist (Marxist-Leninist) dictatorship that successfully took Laos from being a dirt-poor post-colonial state to a dirt-poor ideologically communist state in the present day. About 80% of the Laotian population are subsistence rice farmers.[2] The Lao ethnic group dominates government and society but only comprises about 53% of the population.[3] Ethnic minorities, especially the Hmong people, face persecution. Its capital and largest city is Vientiane.

Laos traces its historical and cultural identity to Lan Xang, a Medieval-era kingdom that was once one of the major hitters in Southeast Asia. The kingdom's ability to take advantage of trade routes in the region led to it becoming rich and powerful. In the mid-1700s, though, Lan Xang fell apart due to succession disputes. The smaller successor states were trapped between hungry neighbors Vietnam and Thailand, who back-and-forth occupied the region and subjected it to slave-hunting raids.

In 1893, France plucked Laos out of the hands of its former oppressors and integrated it into the French colonial empire. Sadly, the French proved to be just as bad, subjecting the region's people to a forced labor regimen and economic exploitation. During World War II, Laos tried to play the French and Japanese off each other to gain freedom, but France simply reoccupied it after the conflict's end. A communist-led independence organization, the Pathet Lao, battled the French alongside the Viet Minh and successfully forced the French to concede Indochina's independence.

Laos became an independent constitutional monarchy in 1953, but the Pathet Lao weren't about to accept a crowned ruler. Backed by the Soviet Union, the Pathet Lao began a civil war against the monarchist forces that eventually got sucked into the Vietnam War. The communists won out in 1975 and remained dependent on economic aid. When the Soviet Union ended, so did the aid tugboats. Laos has been an impoverished and authoritarian state ever since.

Historical overview[edit]

Early history[edit]

Due to its location on the Mekong River and the great potential for rice cultivation, Indochina developed advanced civilizations quite early. India heavily influenced these cultures, which had also developed states around the Bengal area. They had strict hierarchies and class structures, with aristocrats on top, followed by oppressed commoners and then slaves.[4]

At first, though, things were relatively good here. The southern Silk Road brought trade back and forth between Imperial China and India. Alongside trade goods, religions like Hinduism and Buddhism arrived, creating a religious landscape that still shows today. During the early Medieval era, the Khmer Empire from Cambodia reigned supreme here, but it came into frequent conflicts with neighboring Thais and Vietnamese.[4] The Khmer also built temples everywhere as an ostentatious expression of the Buddhist faith. These wars and the constant spending brought down the Khmer Empire through sheer attrition, creating a power vacuum and a golden opportunity for anyone who wanted to conquer everything.

That power vacuum would not be filled by a regional power. Instead, the Mongols kicked in the doors, establishing the Yuan dynasty in China to exercise ruthless influence over Southeast Asia for decades after that. The Sukhothai, an early Thai dynasty, eagerly rushed to act as the Yuan dynasty's agent in collecting tribute; they were rewarded with vast swaths of Southeast Asian territory.[5] In 1308 CE, though, they made the mistake of trying to invade Vietnam, which never went well. Weakened by defeat, the Sukhothai were left vulnerable to its conquered people, who didn't much appreciate being ruled by the Thai, who were ruled by the Mongol Chinese dynasty.

Lan Xang[edit]

After being exiled from his own family, a Khmer prince named Fa Ngum put together his own army to conquer his own kingdom.[6] This kingdom became known by the actually pretty badass name Lan Xang, the kingdom of "Million Elephants and White Parasols". Who wants to fuck with a place called "Million Elephants"? Unfortunately for the Lao, the Vietnamese and the Thai were among those who did want to.

Amid internal conflict between the different Buddhist schools, Lan Xang had to fight a long series of wars with its neighbors for almost the entirety of its existence.[7] The thinly populated kingdom could barely afford this. Despite all of that trouble, though, the Lan Xang managed to unite the highly tribal people of the Laos region and effectively define what would be considered Lao culture.[8] It also lasted for a pretty long time, surviving for 300 years before its eventual destruction.

Laotian dark age[edit]

In 1690, though, Lan Xang fell apart due to internal problems rather than external ones. There were three different claimants to the throne, and their civil war left Lan Xang split into three weakened kingdoms.[7] These kingdoms proved to be easy pickings for their more powerful Thai and Vietnamese neighbors, and they spent the next century being kicked around like footballs. The Thai were especially notorious and hated for launching expeditions into Laos to capture slaves and force-march them off to Siam.[9]

During this darkest period of Lao history, a new group of people migrated into the region. The Hmong people from southern China entered the area to seek better cropland and settled down to grow opium as a cash crop.[7] The Hmong did their best to peacefully coexist, but it was clear that they were resented as newcomers.

In 1826, King Anouvong of Vientiane attempted to free his kingdom from occupation by Siam. His rebellion failed, though, and it resulted in his capture and the complete destruction of the ancient city of Vientiane.[10] The ill-advised war was so damaging to his kingdom that it basically ensured that Laos would remain under Thai rule for the foreseeable future. King Anouvong is revered as a Lao national hero representing perseverance.[11]

French colonial rule[edit]

Throughout the 19th century, France expanded its interests in Indochina by sending expeditions and shaking hands with local rulers. They even saved the life of a Lao king in 1887, earning the ruler's thanks and a promise to enter a protectorate agreement with France.[12] With help from local Laotians, the French expelled the Thai occupiers from Laos and replaced them with their own colonial rulers. Laos became an effective French colony in 1893.

The French gave Laos its name and its present borders. The French basically neglected the region, mainly considering it useful as a buffer state between Siam, the British, and the more crucial French possession of Vietnam.[13] The French figured out that the Mekong River was not navigable into southern China, meaning that the French couldn't send trade ships there.

In the hopes of making Laos pay for itself, the French introduced the corvée labor system, in which Laotians were forced into effective slave conditions to build roads, grow cash crops, and mine tin.[14] The French also burdened the Laotian people with heavy taxation, inspiring some anti-colonial revolts. Despite this, the French population in Laos remained small, and the colony never turned a profit for its overlord. Poor, poor France.

Nationalism was slow to develop in Laos since the French (rather reasonably) claimed that their rule benefited Laos by protecting it from Siam.[14] The Laotians resented the French policy of importing Vietnamese to make up for Laos's small population and labor shortages.

In World War II, the Vichy France government handed Laos and the rest of Indochina to the Japanese occupation. Thailand was Japan's ally, and the French agreed to hand off big chunks of Laotian territory back to Thai rule.[15] The Laotian people were very pissed off at this, as they hadn't been invited to that particular meeting. With the Japanese in charge of the rest of Laos, King Sisavang Vong declared his independence with Japanese support. Once the Japanese surrendered, the king renounced that declaration. This became a point of conflict between him and the increasingly influential Pathet Lao, which had fought the Japanese and hoped to fight the French.[14]

Independence and the Pathet Lao[edit]

Following Japan's defeat in the war, France swiftly attempted to reoccupy its Indochinese colonies, sparking the brutal First Indochina War as the Viet Minh rose against them. To prevent a similar uprising in Laos, France promised them a large degree of autonomy and finally fulfilled that promise in 1950.

During this time, there were three main political factions in Laos. First were the pro-neutrality royalists in control of the government, then there were the pro-French royalists, and finally, the communist Pathet Lao.[16] It didn't take long for the royalists to team up against the communists, and Laos was a country at war when France granted its independence in 1953.

Meanwhile, the Pathet Lao was also heavily involved in Vietnam's war against France. Its leader, Souphanouvong, traveled to Vietnam to work with Ho Chi Minh and even marry a Vietnamese woman.[17] In its early days, the Pathet Lao operated almost as a branch of the Viet Minh. Its North Vietnamese allies remained in Laos even after the 1954 Geneva Convention ordered everyone to go home.[18] Laos' two northeastern provinces, Hua Phan and Phongsali, became the base of operations from which the Pathet Lao and their Vietnamese friends would spend the following years preparing for the inevitable war.[16] The Pathet Lao also got a dramatic boost from the People's Republic of China. Mao Zedong's communist forces had won a victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949 and started shipping mass-produced weapons down south.

It was clear that Laos would not last as a country from the very beginning. It was born out of war and torn apart by the ideological divides of the Cold War and its own people. Despite numerous attempts to create a united coalition government, efforts at unity collapsed by 1958, and both sides decided that war was the only way to resolve their differences.

Civil war[edit]

The conflict had already been simmering for a while. The Vietnam War had begun in 1956, and the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese occupied significant portions of Laotian territory to establish the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[19] Fighting escalated dramatically after the coalition talks broke down in 1959. The Pathet Lao quickly proved far more effective at fighting in the Laotian countryside, as they had already seen similar action against the French.[20] The monarchists had to fall back against the communists' superior tactics, and it became clear that the Pathet Lao was winning.

The United States supplied significant financial and military aid to the Laotian monarchist government, which you should have expected. With the monarchists dependent on that aid for survival, the US government was able to use the threat of suspending aid as a tool to prevent any Laotian plans of reaching any peaceful solution to the war.[20] The US was in full "domino theory" mode and would not accept an outcome where the Pathet Lao had any say in the Laotian government. Representative government? What's that? The US used its aid influence to scuttle peace talks on multiple occasions. Meanwhile, the North Vietnamese also got more involved in the Laotian War.

With the Vietnamese communists able to use the Ho Chi Minh Trail with impunity, the US decided in 1964 to launch Operation Barrel Roll. A secret air support and bombing campaign was undertaken to destroy the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[21] Like most other US strategic air operations in Indochina, it failed. The bombing mission did, though, cause utter ruination in Laos. From 1964 to 1973, the US dropped more than two million tons of ordnance on Laos during 580,000 bombing missions—equal to a planeload of bombs every 8 minutes, 24-hours a day, for 9 years – making Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in history.[22] Needless to say, the bombing caused horrific destruction and misery in Laos. The US raids indiscriminately flattened villages, displacing hundreds of thousands of Laotian civilians.[22]

Despite the bombing, the Pathet Lao still only got stronger. Its offensives were stalled, but only temporarily, and its popular support got larger due to general anger at the bombing. The US, however, still had another weapon in its arsenal. The Hmong, a minority group that had long had difficulty fitting in with other Laotians, generally supported the US anti-communist campaign. Hmong general Vang Pao led a ground force of about 30,000 soldiers, all trained and equipped by the Central Intelligence Agency.[23] Most of them died, and many Hmong civilians had to flee persecution from the Pathet Lao after the conflict. Much of the Hmong's loss can be attributed to the changing nature of their role. At first, the CIA envisioned them as a guerrilla force, and the Hmong proved to be quite good at this. A little too good, as it turned out. The CIA pressured the Hmong to change their tactics to conventional open warfare, hoping to "take the war to the North Vietnamese".[24] Once out in the open, the Hmong were crushed.

In the end, North Vietnam's victory also benefited the Pathet Lao. After the US withdrew, North Vietnam quickly closed in on Saigon, and the Pathet Lao took Vientiane. By the end of 1975, they were in control of the country.

All in all, the civil war resulted in around 60,000 combat deaths and untold civilian casualties.[25]

Party dictatorship[edit]

“”Demonstrations are highly uncommon in Laos... Only a handful of pro-democracy protests have ever taken place under communist rule, most lasting only minutes before being broken up by authorities.

|

| —David Hutt, Asia Times.[26] |

Since the end of the war, Laos has been ruled by the Lao People's Revolutionary Party. It has been and remains a close ally of Vietnam. Vietnamese officials have great influence over the operations of the Laotian government and Laos itself, under effective military occupation for many years.[27][28] Sisavang Vatthana, Laos' last king, was sent to a re-education camp by the new government, and he died there in 1978.[29]

Laos went on a highly austere path to "communism", relying mainly on foreign aid and making almost no economic developments.[30] When Soviet aid started to slow in the 1980s, Laos decided to dip its toes into the Vietnam/China road and open itself to limited foreign investment. Predictably, the economic fruits of those business ventures went almost entirely to the Party elites while the vast majority of the Laotian population remained in grinding poverty.[30] Even when Laos celebrated its 30th anniversary of Party rule, it remained one of the poorest countries in Asia, with most of the population living on the equivalent of about $1 per day.[31]

Even after the fall of the Eastern Bloc and the partial embracement of an authoritarian take on capitalism by neighboring Vietnam and China, Laos remains a dictatorship stuck in the past.

Government and politics[edit]

Lao People's Revolutionary Party[edit]

Laos is a country characterized by the harsh rule of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP). Although its rule is characteristically strict, like most other party dictatorships, the LPRP has recently become somewhat shy about touting its links to other historical communist dictatorships.[32] It notably does not have any statues of Karl Marx or Vladimir Lenin, or any other (in)famous communist thinkers.

Even with a seemingly loosening ideology, the party's leadership style remains autocratic and repressive. Knowledge and political power are tightly controlled. Only a tiny circle of people at the very top of the party apparatus even know what's actually going on.[32] The Lao People's Revolutionary Party is, as you'd expect, the sole legal party in Laos.

Corruption[edit]

Also, typically of communist dictatorships, Laos and its party are rife with irredeemably corrupt officials. Embezzling state funds across all government departments costs Laos billions in its currency every year, even with constant anti-corruption investigations.[33]

Laos' government will "discipline" party officials for stealing money every now and then. However, criminal charges are exceedingly rare due to those officials being members of the party.[34] Due to the party's seeming inability to effectively police itself, corruption is only getting worse.[35]

Social structure[edit]

Before the Pathet Lao took over, Laos was a deeply conservative monarchy state where power was controlled by a handful of families. Pathet Lao's "revolution" did nothing at all to change this. The old aristocracy lost its privileges, but a new elite class arose from high-level power holders inside the Lao People's Revolutionary Party.[36] The new elite class demands similar deference as the old elite class, while the vast majority of the Laotian people saw very little change in their lives.

This pattern of renewed aristocracy under "communism" began all the way back with the original Pathet Lao leader Kaysone Phomvihane, who was the first leader of Laos after the takeover. Kaysone and his cronies led carefully protected lives behind the walls of their guarded compounds in the capital, secluded from public scrutiny and shielded from any popular feedback on their actions.[37]

Human rights[edit]

Considering all of the above, it's no surprise that Laos has a very severe record of human rights abuses.

Persecution of the Hmong people[edit]

Laos' communist government never really got over how the Hmong people supported the CIA during the civil war. After the war, the Hmong were forced out of their homes and communities and excluded from the new Laotian state. They've been hiding in the jungles with nowhere else to go for decades while facing attacks and massacres from the military that are still ongoing.[38]

Some Hmong have attempted to reintegrate into Laotian society. Those Hmong who are unfortunate enough to cross paths with Laotian government officials or police face extremely dangerous racism. Due to their history, the Laotian government makes it official policy to treat Hmong civilians with the utmost suspicion. This includes targeting people for arbitrary reasons and selecting them for brutal interrogation bordering on torture.[39] Along with the usual scourges of arbitrary imprisonment and torture, Hmong women also risk being raped or forced into sexual slavery with no chance of freedom or justice.[40]

Freedom of speech and assembly[edit]

In suppressing speech, Laos has proven to be one of the most repressive countries in the entire region. The Laotian government, corrupt and self-serving, is especially zealous in preventing people from speaking out against its own wrongdoing. To offer an example, in 2015, a woman named Phout Mitane was arrested and detained for two months without due process after a photograph she took appearing to show police extorting money from her brother was posted online by someone else.[41] In another instance, a man named Bounthanh Thammavong was sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison for criticizing the ruling party on Facebook. Laos also has multiple high-profile human rights activists in prison, and it refuses to provide any information confirming that they're even alive.

Foreign journalists in Laos are subject to harsh restrictions as well. Before publishing anything, they have to submit their work to Laotian government censors, and they are to be accompanied at all times by government chaperones.[41]

Torture and mistreatment[edit]

Laos' prisons subject inmates to horrific conditions. Prison cells are overcrowded, with beds no wider than 50 centimeters and juveniles housed with adults to save space.[42] Laos refuses to provide information related to the deaths of incarcerated due to mistreatment. Still, reports and complaints occasionally make their way out of people dying due to overheating, disease, or malnutrition.[42] If all of that wasn't shitty enough, prisoners after release also have to reimburse the Laotian state for the costs of keeping them incarcerated. Gotta love that "communism", huh.

The Laotian government also does a competent job of keeping their torture practices under wraps. Still, once again, reports have surfaced that they routinely use electric shocks and deliberate food deprivation to torment political prisoners.[42]

Gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ See Who's Asia's No. 2 Police State After North Korea, And It's Not China. Forbes.

- ↑ Laos country profile. BBC News.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Demographics of Laos.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Laos: Early History. Country Studies.

- ↑ Laos: Mongol influence. Country Studies.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1. p.223

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Laos: Lan Xang. Country Studies.

- ↑ Lan Xang. Facts and Details.

- ↑ Slavery in Nineteenth-Century Northern Thailand: Archival Anecdotes and Village Voices. Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Lao rebellion (1826–1828).

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Anouvong.

- ↑ French control of Laos. Facts and Details.

- ↑ Cummings, Joe and Burke (2005). Laos. Lonely Planet. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-74104-086-9.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Laos. Lonely Planet.

- ↑ Laos: World War II. Country Studies.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Laos Road to Independence. Facts and Details.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Souphanouvong.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Pathet Lao.

- ↑ Laos During the Vietnam War. Alpha History.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 First Coalition of Laos, Civil War and Elections. Facts and Details.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Operation Barrel Roll.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Secret War in Laos. Legacies of War.

- ↑ Apocalypse Laos: America Loses the Laotian Civil War to the Communists. Readex.

- ↑ Review | History of Laos’ secret war – and the way it transformed the CIA – reveals a sobering legacy. South China Morning Post.

- ↑ Obermeyer, Ziad; Murray, Christopher J. L.; Gakidou, Emmanuela (2008). "Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme". BMJ. 336 (7659): 1482–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.a137. PMC 2440905. PMID 18566045.

- ↑ Laos democrats fight a lonely losing struggle. Asia Times.

- ↑ Stuart-Fox, Martin (1980). LAOS: The Vietnamese Connection. In Suryadinata, L (Ed.), Southeast Asian Affairs 1980. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Stuides, p. 191.

- ↑ Savada, Andrea M. (1995). Laos: a country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, p. 271. ISBN 0-8444-0832-8

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Sisavang Vatthana.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Communism in Laos: Poverty and a Thriving Elite. New York Times.

- ↑ Laos marks 30 years of communist rule. Irish Times.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Government of Laos. Facts and Details.

- ↑ Laos counts the cost of corrupt government officials. Nation Thailand.

- ↑ Laos ‘Disciplines’ Hundreds of Corrupt Officials in Recent Months, Jails Few. Radio Free Asia.

- ↑ Corruption Still Rife in Laos Despite Continued Crackdown Efforts. Radio Free Asia.

- ↑ Laos Government. Country Studies.

- ↑ Developments in the Lao People's Democratic Republic. Country Studies.

- ↑ WGIP: Side event on the Hmong Lao, at the United Nations. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization.

- ↑ Thousands Still Risk Torture For Helping U.S. in Vietnam War. NBC News.

- ↑ Hmong: Suffering of the Hmong Highlighted During Captive Nations Summit. Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 The questions Laos doesn’t want to answer. Amnesty International.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 2019 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Laos. US State Department.