Infinite regress

| Cogito ergo sum Logic and rhetoric |

| Key articles |

| General logic |

| Bad logic |

“”Big fleas have little fleas,

Upon their backs to bite 'em, |

| —The Siphonaptera poem by Augustus De Morgan[1] |

An infinite regress or homunculus fallacy is when an argument relies on a series of never-ending propositions, where the validity of one proposition depends on the validity of the one which follows and/or precedes it.

The infinite regress is a close sibling of circularity, wherein the premises provide support for the conclusion, which in turn provides support for said premises to begin with, which in turn…[2]

Why it's logically fallacious[edit]

“”Neither can there be a separated infinite number: for number, or what has number, is countable, and so, if it is possible

to count what is countable, it would be possible to traverse the infinite.

|

| —Aristotle |

Aristotle posits an argument that shows an infinite regress to result in a contradiction. Formed using predicate logic, the proof reads like this:

- Nx⊃Cx

- Cx⊃Tx

- ∴Nx⊃Tx (1, 2 hypothetical syllogism)

- Ix⊃~Tx

- | ∃x(Nx·Ix)

- | Na·Ia

- | Na (6, simplification)

- | Ta (3, 7 modus ponens)

- | Ia (6, simplification)

- | ~Ta (4 , 9 modus ponens)

- | Ta·~Ta (8, 10 conjunction)

- QED ∃x(Nx·Ix) results in a contradiction

- ∴There does not exist a number that is infinite

Let's define the terms. Nx⊃Cx reads "if x is a number, then x is countable." Cx⊃Tx reads "if x is countable, then x is traversable." Ix⊃~Tx reads "if x is infinite, then x is not traversable." ∃x(Nx·Ix) reads "there exists an x such that x is a number and x is infinite," and is a supposition for the sake of argument. Now, 'countable' and 'traversable' need to be defined. Aristotle regarded numbers as made up of composite parts. If Aristotle had thought of the number 42, he would have thought that it was composed of 42 individual parts. This is what he means by 'countable'. 'Traversing' is the act of counting. So, if a number is countable, then counting the individual parts and finally reaching the number is traversing, which means the number is traversable. Aristotle says that if a number is truly infinite, it can't be traversed because the end of the number can't ever be reached. Given the definitions of the terms and the logical validity of the argument, Aristotle concluded that there exist no infinite numbers.

Examples[edit]

Intelligent design[edit]

One example of a viciously infinite regression arises in intelligent design creationism, which states that there are problems in the theory of Darwinian evolution by natural selection which can only be resolved by invoking a designer or first cause without proposing a solution to the immediate question, "Who designed the designer?" Despite that, the response to this is an example of special pleading: creationists assert that every being needs a cause, but God is an eternal presence which did not need a cause. No evidence for this has ever been presented for peer review, or critical analysis of any kind.

Turtles[edit]

The "Turtles all the way down"![]() anecdote illustrates a popular example of infinite regress:

anecdote illustrates a popular example of infinite regress:

“”A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the center of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: "What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise." The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, "What is the tortoise standing on?" "You're very clever, young man, very clever", said the old lady. "But it's turtles all the way down!

|

| —Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time |

Homunculi[edit]

The term "homunculus" first appeared in Paracelsus'![]() writing on alchemy, De Natura Rerum (1537),[3] referring to what later became known as sperm after the invention of the microscope. In folklore and in literature, the term "homunculus" often refers to a miniature fully-formed human.[3]

writing on alchemy, De Natura Rerum (1537),[3] referring to what later became known as sperm after the invention of the microscope. In folklore and in literature, the term "homunculus" often refers to a miniature fully-formed human.[3]

In the Eastern Bloc, homunculus has referred to attempts to remold people to be "without sexual, high intellectual or high emotional 'centres'".[4]:178[5] More recently, Daniel Kalder has used homunculus to refer primarily to the heads of puppet states who felt compelled to follow the party line while at the same time not showing any innovation from the party canon.[6] Stalinist examples include Khorloogiin Choibalsan![]() of Mongolia, Georgi Dimitrov

of Mongolia, Georgi Dimitrov![]() of Bulgaria, Klement Gottwald

of Bulgaria, Klement Gottwald![]() of Czechoslovakia, Enver Hoxha of Albania, Kim Il Sung of North Korea, and Konstantin Chernenko

of Czechoslovakia, Enver Hoxha of Albania, Kim Il Sung of North Korea, and Konstantin Chernenko![]() of the Soviet Union.[6]:212,216,242,252,279

of the Soviet Union.[6]:212,216,242,252,279

Motor homunculus[edit]

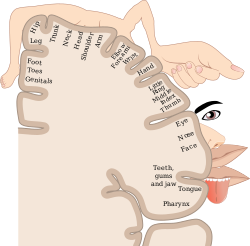

The motor homunculus or somatotopic homunculus, is a visualization tool used in neuroanatomy to illustrate which parts of the brain control which parts of the body.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- See the Wikipedia article on Infinite regress.

- HOMUNCULUS FALLACY, Logically Fallacious

- The "Fallacy" of Infinite Regress, Michigan Secular Students Alliance

References[edit]

- ↑ The Poetry of John Milton by Gordon Teskey (2015) Harvard University Press. p. 480. ISBN 0674416643.

- ↑ And so on, in a looping infinite regress.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 See the Wikipedia article on Homunculus.

- ↑ Literature in Post-Communist Russia and Eastern Europe: The Russian, Czech and Slovak Fiction of the Changes 1988-1998 by Rajendra Anand Chitnis (2004) Routledge. ISBN 0415355575.

- ↑ Чапаев: Место рождение - Рига. In: Цыганский роман by Андрей Левкин (2000). Амфора.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The Infernal Library: On Dictators, the Books They Wrote, and Other Catastrophes of Literacy by Daniel Kalder (2018) Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 1627793429.

- ↑ A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex by Evan M. Gordon et al. (2023) Nature 617:351–359. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05964-2. Page 357 has the updated map.