Belgian Congo

| The colorful pseudoscience Race & Racialism |

| Hating thy neighbour |

| Divide and conquer |

| Dog-whistlers |

| The white man's burden Imperialism |

| The empires strike back |

| Veni, vidi, vici |

“”At the time of the Congo Free State, acts of violence and cruelty were committed that still weigh on our collective memory. The colonial period that followed also caused suffering and humiliation. I would like to express my deepest regrets for these wounds of the past, the pain of which is today rekindled by the discrimination still too present in our societies.

|

| —King Philippe, constitutional monarch of Belgium[1] |

The Belgian Congo, also known as the Congo "Free" State, was a Belgian colony in the geographic area that is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo which became infamous for its brutal forced labor regime[2][3][4] which killed between one and ten million people.[5]

Background[edit]

Colonial exploitation of the Congo occurred in two phases. First, King Leopold II of Belgium took personal control of the territory (meaning that it was owned not by Belgium™, but by Leopold as an individual, because all the colonial powers wanted the Congo and this way its resources could be sold to everyone) and gave it the hideously ironic name of the "Congo Free State" (1885-1908).[6]

After international outcry over the brutality inflicted on the Congolese natives, the Belgian government reluctantly confiscated the territory from Leopold and instituted a marginally less murderous regime (less murderous in that it only killed one million people[7]). Like many countries which suffered under the Scramble for Africa, the legacy of the Belgian Congo looms over the current DR Congo, even if not acknowledged in any form, by any media.

The Congo "Free" State (1885‒1908)[edit]

During the 1880s and beyond, the major European powers were rapidly dividing and colonizing Africa in a period known as the Scramble for Africa. To prevent colonial conflicts from occurring on the continent, the European powers met at the Berlin Conference to hammer out some ground rules. Among other things, this meeting confirmed the Congo Free State as being the private property of King Leopold II. No, not Belgium. Leopold as an individual specifically.[8]

Leopold II of Belgium[edit]

Leopold managed to convince the European powers to agree to this by explaining that he wanted to help "civilize" the natives and convert them to Christianity.[9] He argued that Belgian rule would be for their own good. This appealed to the other European leaders because they were using much the same rhetoric to justify colonialism themselves.[10][11] Unfortunately, for the Congolese, Leopold was lying his ass off.

Initially, the colony was a financial failure. However, the rubber boom happened,[12] and Belgian explorers stumbled across a huge number of rubber vines native to the Congo.[13] At this point, Leopold began to turn the Congo into a Hell on Earth. Villages of natives were forced to venture out into the jungles and gather rubber. This was a painful and labor-intensive process, especially because the best way to harvest rubber while keeping the trees alive for more harvesting was to slice the vines, allow the latex sap to cover the body and dry, then peel it off along with skin and hair.[14] The native laborers were given quotas by their overlords, and failure to meet them would be met with arson, rape, whippings, and massacres.[15]

The quotas themselves were insane, motivated by nothing but sheer profit. The Anglo-Belgian Rubber (ABIR) Congo Company was the primary agent assigned by Leopold to produce rubber from the Congo, and they made massive profits by selling rubber for almost ten times as much as it cost to produce.[16] The desire to maximize production (and thus profits) led to an issuance of production quotas that had no consideration at all for what was realistically possible. Meanwhile, the lack of any formal bureaucracy on the ground gave administrators leeway to be as brutal as possible in the likely event that the Africans were unable to produce inhumanely large quantities of rubber.[17]

State-sponsored violence[edit]

Leopold and the ABIR Company's colonial administrators hired mercenaries to enforce their demands, and infamously mandated that they sever the hands of anyone they killed to prove that they weren't wasting bullets on hunting or sport.[18] Government-issued guns are only for shooting people, y'see. Of course, the undisciplined mercenaries couldn't help themselves, so in order to cover it up, they just raided villages and severed hands from living people.[19]

Severed hands even became a commodity of sorts as villages used them to bribe mercenaries to avoid punishment for failure to meet quotas. This resulted in small wars between villages as they attempted to gather hands from other natives.[20] King Leopold disapproved of the mutilations, but not due to humanitarian reasons. He was quoted as saying "Cut off hands - that's idiotic. I'd cut off all the rest of them, but not hands. That's the one thing I need in the Congo."[21]

Global attention[edit]

While the images of severed hands became the greatest symbol of Belgium's brutality in the Congo, it was only the tip of the iceberg. Belgian authorities ordered the razing of entire villages and the murder of all of their inhabitants in the event of any resistance or repeated failures to meet quota.[22]

Needless to say, this kind of treatment did not take long to be noticed. E.D. Morel, a British journalist, was the first to notice something rotten in the heart of Africa. He was working at a shipping company at the time and noticed that while great wealth flowed out of Congo Free State, the only things that were ever shipped back in were weapons, ammunition, and tools of bondage. Eventually, the international public got wind of what was happening in the Congo, beginning with the publication of the Casement Report![]() by a national of the United Kingdom and further inflamed with Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness

by a national of the United Kingdom and further inflamed with Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness![]() and Mark Twain's King Leopold's Soliloquy

and Mark Twain's King Leopold's Soliloquy![]() . This international outcry and intense diplomatic pressure forced the Belgian Parliament to officially annex the Congo as a possession of the Belgian state.[23]

. This international outcry and intense diplomatic pressure forced the Belgian Parliament to officially annex the Congo as a possession of the Belgian state.[23]

Belgian Congo (1908‒1960)[edit]

Theoretically, things should have gotten better. In some respects they did, essentially with the passage of legislation outlawing the "red rubber" system detailed above and most of the worst instances of violence. However, many other laws, especially the ones banning forced labor as a whole, were completely ignored due to a lack of administration on the ground.[24] Corporations operating in the Congo and even the Belgian government itself continued to use slave labor in the Congo, albeit using slightly less obvious and egregious methods.[25] Indeed, the vast majority of the administrators appointed by Leopold remained in place under the new regime despite their myriad crimes.[26]

Natives who failed to do the work were sent to prison, and then punished via chicotte, a type of whip made from hippo hide.[27] For a time, the Congolese were still forced to gather rubber, but just before World War I, the price of rubber fell as rubber plantations elsewhere in the world began producing. By then, the wild rubber vines in the Congo were largely tapped out.[28]

Doctors and officials reported on how little the Belgian government cared about natives. Natives received very little education and just as much healthcare.[29][30]

A report published by these doctors in 1923 noted that "It is of course the case that when an entire population is put to work, in a manner harmful to its very existence, it cannot be a question of voluntary labour."[29] By threats of prison and the chicotte, workers were forced to work from morning until night.[29] While the work was painful enough for an adult, it was an intolerable strain for old men and the infirm, who made up the majority in certain fields of labor, such as palm fruit harvesting. Unable to supply the required quantities by themselves, the men had to call upon their wives to help them. Children were forced to work too.[29] At one point mentioned by the report, children aged 5 to 14 made up the entire workforce. This intense forced labor regime resulted in a decline of food cultivation, causing famines and disease.

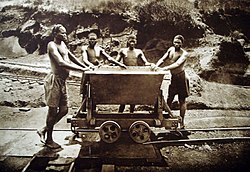

Other Congolese were forced to work in the mines. Laborers were taken from their homes and marched to the mines with ropes around their necks, under the guard of undisciplined soldiers. Upon arrival, they found unhealthy working conditions, a heavy, stamina-draining workload, insufficient food for the output of energy required, and near constant physical abuse.[31] Some men were jailed for complaining to management about their wives being raped, and whipped if they persisted in complaining.[31]

The Huileries du Congo Belge (HCB), a subsidiary of Lever Brothers, was one of the companies that recruited Africans by force, their numerous agents accompanied by armed auxiliaries. The agents encountered increasing resistance during their tours, or else found villages emptied before they arrived.[32] Dr. Émile Lejeune, medical officer of the Congo-Kasi province, drafted a report finding rations, accommodation, and clothing to be inadequate, and the workload to be dangerous for the health of even healthy young men.[29]

A number of workers were dying, and while Lejeune found documentation of rates of mortality to be inadequate, he found the most frequent causes of death recorded to be disease, especially pneumonia and bronchial infections.[29] The HCB provided blacks with just one meal a day, and due to lack of pans and utensils, the preparation was often unhygienic and unpleasing.[29] No clothing or blankets were provided, which was a major problem since the majority of deaths were caused by respiratory ailments.[29] Labor camps were crowded and lacked latrines, kitchens, medical facilities, and even a place to dispose of trash.[29]

Jules Marchal, who was a colonial official in the Belgian Congo between 1948 and 1960, himself administered punishments with the chicotte during that time to force natives to grow cotton. He must have had a change of heart, since he later proceeded to write a number of books revealing the brutality of the regime he served and of the previous regime, King Leopold's Congo "Free" State.[33][34][35]

Matters eventually came to a head in 1960, with the eruption of the Congo Crisis and the Belgian Congo's subsequent independence.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Belgian king expresses ‘deepest regrets’ for historical Congo brutality. Financial Times

- ↑

- Buell, Raymond Leslie (1928). The native problem in Africa, Volume II. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 540–544.

- Likaka, Osumaka (1997). Rural Society and Cotton in Colonial Zaire. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Marchal, Jules (1999). Forced labor in the gold and copper mines: a history of Congo under Belgian rule, 1910-1945. Translated by Ayi Kwei Armah (reprint ed.). Per Ankh Publishers.

- Hochschild, Adam (1999). "18. Victory?". King Leopold's Ghost: a story of greed, terror, and heroism in colonial Africa. Boston: Mariner Books.

- Marchal, Jules (2008). Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4.

- Rich, Jeremy (Spring 2009). "Lord Leverhulme's Ghost: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo (review)". Project Muse. Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑

- Makelele, Albert (2008). This is a Good Country: Welcome to the Congo. pp. 43–44.

- Lewis, Brian (2008). "Sunlight for Savages". So Clean: Lord Leverhulme, Soap and Civilisation. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 188–190.

- Zoellner, Tom (2009). "1 Scalding Fruit". Uranium: war, energy, and the rock that shaped the world. New York: Penguin Group. pp. 4–5.

- Edmondson, Brad (2014). "10: The Sale Agreements". Ice Cream Social: The Struggle for the Soul of Ben & Jerry's. San Francisco, California: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- De Witte, Ludo (January 9, 2016). "Congolese oorlogstranen: Deportatie en dwangarbeid voor de geallieerde oorlogsindustrie (1940-1945)". DeWereldMorgen.be. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "Lord Leverhulme". History. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑

- Mitchell, Donald (2014). The Politics of Dissent: A Biography of E D Morel. SilverWood Books.

- "Un autre regard sur l'Histoire Congolaise: Guide alternatif de l'exposition de Tervuren" (PDF). pp. 14–17, 25–28. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Seconde partie : Travail forcé pour le cuivre du Katanga https://www.cobelco.info/Histoire/Congo2text.htm

- Troisième partie: Travail forcé pour l'or https://www.cobelco.info/Histoire/travfor_or.htm

- ↑ 'King Leopold's Ghost': Genocide With Spin Control Kakutani, Michiko. New York Times. September 1, 1998

- ↑ Marchal, Jules (2008). "Introduction by Adam Hochschild". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. p. xix. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4.

- ↑ I recorded no democide for Belgium, although it may have been responsible for close to a million once it took over the Congo https://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/COMM.7.1.03.HTM

- ↑ Full Text of the General Act of the Berlin Conference on West Africa

- ↑ 1885: Belgian King Establishes Congo Free State National Geographic

- ↑ The Mission Civilisatrice (1890-1945)

- ↑ Robert Livingston Schuyler, "The rise of anti-imperialism in England." Political science quarterly 37.3 (1922): 440-471. in JSTOR

- ↑ Development of the natural rubber industry

- ↑ Gumvines "Lost Crops of Africa: vol III"

- ↑ HOW HEART OF DARKNESS REVEALED THE HORROR OF CONGO’S RUBBER TRADE Literary Hub

- ↑ Belgium's Heart of Darkness Stanley, Tim. History Today Volume 62 Issue 10. October 2012.

- ↑ Father stares at the hand and foot of his five-year-old, severed as a punishment for failing to make the daily rubber quota, Belgian Congo, 1904 Rare Historical Photos.

- ↑ Gibbs, David N. (1991). The Political Economy of Third World Intervention: Mines, Money, and U.S. Policy in the Congo Crisis. American Politics and Political Economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Red Rubber: Atrocities in the Congo Free State in Confidential Print: Africa

- ↑ Renton, David; Seddon, David; Zeilig, Leo (2007). The Congo: Plunder and Resistance. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-485-4.

- ↑ Hochschild, King Leopold's Ghost, p. 166

- ↑ The hidden holocaust The Guardian. 1999-05-13

- ↑ Stengers, Jean (1969). "The Congo Free State and the Belgian Congo before 1914". In Gann, L. H.; Duignan, Peter. Colonialism in Africa, 1870–1914. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 261–92.

- ↑ Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa: the White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912 (13th ed.). London: Abacus. pp. 588–9. ISBN 978-0-349-10449-2.

- ↑ Marchal, Jules (1999). Forced labor in the gold and copper mines: a history of Congo under Belgian rule, 1910-1945. Translated by Ayi Kwei Armah (reprint ed.). Per Ankh Publishers.

- ↑ Hochschild, Adam (1999). "18. Victory?". King Leopold's Ghost: a story of greed, terror, and heroism in colonial Africa. Boston: Mariner Books.

- ↑ Stengers, Jean (2005), Congo: Mythes et réalités, Brussels: Editions Racine.

- ↑ Marchal, Jules (2008). "Afterword". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4. First published as Travail forcé pour l'huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: L'histoire du Congo 1910-1945, tome 3 by Editions Paula Bellings in 2001.

- ↑ Marchal, Jules (2008). "Introduction by Adam Hochschild". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 Marchal, Jules (2008). "2: The Lejeune Report (1923)". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. pp. 27–36. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4. First published as Travail forcé pour l'huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: L'histoire du Congo 1910-1945, tome 3 by Editions Paula Bellings in 2001.

- ↑

- Marchal, Jules (2008). "4: In Barumbu Circle (1917-1930)". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4. First published as Travail forcé pour l'huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: L'histoire du Congo 1910-1945, tome 3 by Editions Paula Bellings in 2001.

- Marchal, Jules (2008). "5: In the Basongo and Lusanga Circles (1923-1930)". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4. First published as Travail forcé pour l'huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: L'histoire du Congo 1910-1945, tome 3 by Editions Paula Bellings in 2001.

- Marchal, Jules (2008). "7: The Compagnie Due Kasai Proves to be Worse Than the HCB (1927-1930)". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4. First published as Travail forcé pour l'huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: L'histoire du Congo 1910-1945, tome 3 by Editions Paula Bellings in 2001.

- Marchal, Jules (2008). "7: The Compagnie Due Kasai Proves to be Worse Than the HCB (1927-1930)". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. pp. 121–128. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Marchal, Jules (1999). Forced labor in the gold and copper mines: a history of Congo under Belgian rule, 1910-1945. Translated by Ayi Kwei Armah (reprint ed.). Per Ankh Publishers. pp. 240–242.

- ↑ Marchal, Jules (2008). "1: The Early Years (1911-1922)". Lord Leverhulme's Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo. Translated by Martin Thom. Introduced by Adam Hochschild. London: Verso. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-84467-239-4. First published as Travail forcé pour l'huile de palme de Lord Leverhulme: L'histoire du Congo 1910-1945, tome 3 by Editions Paula Bellings in 2001.

- ↑ Jules Marchal: postuum interview met eenzaam waarheidsvinder – tegen de Belgische Congo-mythes. http://www.sypwynia.nl/archief/interview-jules-marchal/

- ↑ Marchal, Jules 1924-2003. http://worldcat.org/identities/lccn-n96039138/

- ↑ Interview de Jules Maréchal. http://www.larevuetoudi.org/fr/story/poursuite-du-travail-forc%C3%A9-apr%C3%A8s-l%C3%A9opold-ii