Guinea

“”We prefer poverty in liberty to riches in slavery.

|

| —Ahmed Sékou Touré, who went on to give Guinea poverty but no liberty.[1] |

The Republic of Guinea, sometimes called Guinea-Conakry to distinguish it from other countries with "Guinea" in the name, is a nation in West Africa with a predominantly Muslim population. Despite its wealth of natural resources, the vast majority of the people have not seen the profits go to good use. Guinea was historically an exploited colony of the French colonial empire. Its capital is in the city of Conakry.

Guinea was the second black African country (after Ghana) to gain independence from a European power. In France's 1958 constitutional referendum, Guinean voters overwhelmingly rejected the document, which meant immediate independence and a total cutoff from French support.[2] Guinea was the only French territory that chose that path under the dynamic leader Ahmed Sékou Touré, who famously proclaimed that he would prefer poverty in liberty to riches in slavery. However, once firmly in command, Touré cracked down on opposition and sent his opponents to concentration camps to be tortured and, in some cases, starved to death. Guinea now knows neither liberty nor riches. Touré left a legacy of terror and ineffective economic management when he died of cardiac arrest in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1984. Unfortunately, many diehard Pan-Africanists and black nationalists still see Touré as a hero who was possibly murdered by a Western conspiracy.

The country is predominantly Islamic, which is the only thing unifying it since it comprises 24 ethnic groups.[3] About 7% of the population identifies with traditional African folk religion.[4] According to the US State Department, Guinea's government is reasonably good at respecting freedom of religion, although societal discrimination is still a serious problem.[4]

Guinea is an impoverished country, which is stupid because it has a great natural resource wealth. It possesses the world's largest reserves of bauxite and largest untapped high-grade iron ore reserves and gold and diamonds.[5] Guinea has fertile soil and multiple great rivers, such as Senegal, Niger, and the Gambia, potentially allowing Guinea to become a great hydroelectric energy exporter.[5] Sadly, the country is held back by political instability, corruption, and crumbling infrastructure.

Even worse, Guinea has a rather bad human rights record, most notably involving torture and violent suppression of protests by government forces and abuse of women. In February 2020, the US State Department issued a Level 2 Travel Advisory for Guinea, citing the threat that any large crowd of people could be a potential target for a violent crackdown.[6]

Historical overview[edit]

Pre-colonial history[edit]

The land that is now Guinea was part of several notable West African empires. The Mali Empire rose in 1230 and became renowned for the great wealth of its rulers, especially Mansa Musa.[7] Musa famously went on a spending spree on his Hajj, which crashed the value of gold across most of North Africa and the Middle East. He was one of the richest people in history.[8]

Mali was eventually supplanted by one of its vassal states, which grew to become the Songhai Empire in 1464. It ultimately surpassed Mali in territory and wealth, but it later fell due to repeated attacks from the Moroccans.[9] After that, Guinea founded its own state, becoming Futa Jallon, a primarily Muslim state ruled by the Fulani ethnic group.

Guinea became a major hotbed of the Atlantic slave trade, with 95% of African slaves coming from the western African coastline.[10] Prisoners were captured in war and then sold to Europeans to be shipped to colonies in the Americas.

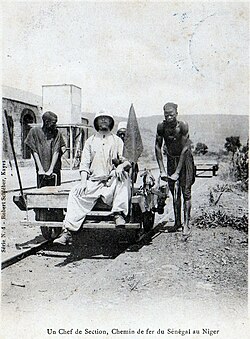

French colony[edit]

France acquired Guinea during the Scramble for Africa, striking a deal with the British Empire to acknowledge each other's holdings in the West African area. Guinea resisted colonialism from the start of French rule until about 1912 when France launched a brutal and murderous expedition to put them down.[11]

France made no effort to educate their new colonial subjects, and many people in Guinea were unaware that they had been colonized. The unfortunate souls that were aware were put to work as forced laborers to strip Guinea of its natural resources, especially rubber, diamonds, and bauxite.[11] Metropolitan France extensively used Guinean soldiers during the two world wars: 36,000 were mobilized in World War I and nearly 18,000 in World War II.[11] As happened in other colonial territories, the world wars awakened a new sense of anti-colonial political consciousness.

The colonial wars in Algeria and Vietnam caused the collapse of the French Fourth Republic, and part of establishing a new political order was figuring out what to do about the colonies. In 1956 came the Loi Cadre, a new legal code that transferred considerable administrative powers to the colonies but fell far short of the independence most Africans had asked for, with France still in control of foreign affairs, currency, and economic matters.[2] The Guineans, who had been long dissatisfied with their treatment at the hands of the French, decided against ratifying the document. The "No" vote was advocated by the Guinea branch of the Rassemblement Democratique Africain (African Democratic Rally [RDA]), an "inter-territorial movement of political parties and groups in Francophone countries in West and Central Africa".[2] Guinea's branch was led by Ahmed Sékou Touré. Having rejected the new agreement, Guinea declared independence in 1958.

Independence and dictatorship[edit]

| —Sylvain Touati, French Institute of International Relations.[12] |

After Guinea suddenly declared independence, the French decided to display just how pissed off they were. For two months, the French destroyed or stole everything they could. They unscrewed lightbulbs, removed plans for sewage pipelines in Conakry, the capital, and even burned medicines rather than leave them for the Guineans.[13] Guinea was basically left with nothing.

Having burned its bridges with France, Guinea had to turn elsewhere for international support in buildings its economy and solidifying its government. In came the Soviet Union with welcoming arms. Touré became the dictator of Guinea, and he turned the country into a one-party socialist dictatorship. Despite dealing with severe infrastructure problems, the Touré regime did nothing to improve things.[2] Touré heavily favored his own Malinke ethnic group rather than maintaining cross-ethnic nationalism, and his authoritarianism drove more than a million people into exile.[14] An estimated 50,000 people were killed in concentration camps by Touré's government.

Guinea was then invaded in late 1970 by Portugal, as Portugal had taken exception to the fact that Touré was a loud advocate of decolonization who was assisting Guinea-Bissau in its war for independence.[15] Some of the Portuguese troops used blackface for disguise.[16] The raid inflicted great damage on Guinea's military assets, but it failed to achieve the goal of eliminating Touré's government.

The declining economy and political repression resulted in the Guinean Market Women's Revolt in 1977, forcing the dictator to relax price controls on Guinea.[17] This culminated with Touré renouncing communism and reestablishing ties with the Western capitalist nations. Although this brought in a flood of Western investment, it did nothing to help the people of Guinea. Touré died in 1984 of heart problems in a Cleveland hospital.

Modern era[edit]

With the dictator gone, several military members led by Lansana Conté launched a bloodless coup to seize control of Guinea's government. President Condé promised the restoration of human rights and fully democratic elections and was elected three times between 1993 and 2003.[18] These promised human rights reforms never came to pass, and Conté ruled until his death in 2008 as a dictator.

Guinea also spent the 2000s teetering on the brink of civil war, as ethnic violence in Sierra Leone and Liberia threatened to spill over.[19] After Conté's death, the military launched yet another coup, sparking protests and crackdowns, leaving about 157 people dead.[20] The new regime's soldiers went on a horrific rampage of rape, mutilation, and murder which caused many foreign governments to withdraw their support for the new regime.[21] Moussa Dadis Camara, the new dictator, was then shot about a year later by one of his aides.

Guinea held its first real election in 2010 after a period of a provisional government.[22] The disputed nature of the election led to ethnic clashes between the Fula and Malinke ethnic groups.[23]

Guinea was one of the worst-hit countries during the 2014 to 2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa.[24]

On September 5th, 2021, President Alpha Condé was ousted in a military coup by Col Mamaday Doumbouya.[25]

Human rights[edit]

Freedom of speech and assembly[edit]

Guinea's government currently bans all street protests, and security forces routinely disperse gatherings with tear gas and live ammunition.[26] Those arrested are frequently given sentences of between 6 and 12 months in prison.

Many media outlets are suspended, and journalists are routinely arrested.[27] At least 61 people were killed by Guinea's security forces between January 2015 and January 2020.[27] Security forces can commit excessive violence and murder with impunity, as Guinea's government never punishes such actions. Indeed, Guinea's National Assembly passed a law in July 2019 to actively shield law enforcement from prosecution over unlawful activities.[26]

Torture and inhumane detention[edit]

Guinea criminalized torture in 2016 and made it punishable with up to 20 years in prison, but this ban is still imperfectly enforced.[27] Guinea's prisons remain overcrowded, and prisoners are often deprived of basic needs. This has led to an alarming number of deaths in custody.

Women and LGBT rights[edit]

Guinea has extremely high rates of rape, often committed by its own security forces, yet it rarely, if ever, prosecutes rape cases.[28] Women also face high levels of discrimination. Despite the practice being illegal, female genital mutilation is prevalent across Guinea, and the practice is also never prosecuted.[28]

Homosexuality and same-sex marriage are also illegal in Guinea.

Death penalty[edit]

In July 2016, Guinea adopted a new legal code that effectively abolished the death penalty for all crimes.[29]

Gallery[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ The speech by Sekou Toure that angered colonial France to pack out of Guinea. Face 2 Face Africa.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Guinea: 1958-present. International Center of Nonviolent Conduct.

- ↑ Ethnic Groups Of Guinea (Conakry). World Atlas.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 GUINEA 2012 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT. US State Department.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Guinea. CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ Guinea Travel Advisory. US State Department.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Mali Empire.

- ↑ The 10 Richest People of All Time. Time Magazine. Archived.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Songhai Empire.

- ↑ Senegal & Guinea. National Humanities Center.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Guinea - French Colony. Global Security.

- ↑ Guinea: war, poverty, dictatorship and bauxite. The Guardian.

- ↑ Guinea's Longtime President, Ahmed Sekou Toure, Dies. Washington Post.

- ↑ Biography of Ahmed Sékou Touré. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Operation Green Sea.

- ↑ U.N. Mission on Guinea Says Portuguese Led Raid. New York Times.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Guinean Market Women's Revolt.

- ↑ Lansana Conté. Britannica.

- ↑ Civil war fears in Guinea. BBC.

- ↑ Guinea massacre toll put at 157. BBC.

- ↑ U.N. Panel Calls for Court in Guinea Massacre. New York Times. Archived.

- ↑ Conde declared victorious in Guinea. IOL.

- ↑ Ethnic Clashes Erupt in Guinea Capital. Voice of America. Archived.

- ↑ 2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-58461971

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 World Report 2020: Guinea. Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 GUINEA: RED FLAGS AHEAD OF THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION. Amnesty International.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2011. US State Department.

- ↑ “How I brought people together and called for Guinea to abolish the death penalty”. Amnesty International.