Haiti

“”A word about Hayti. We are not to judge her by the height which the Anglo-Saxon has reached. We are to judge by the depths from which she has come. We are to look at the relation she sustained to the outside world, and the outside world sustained to her. One hundred years ago every civilized nation was slave-holding. Yet these negroes, ignorant, downtrodden, had the manhood to arise and drive off their masters and assert their liberty. Her government is not so unsteady as we think.

|

| —Frederick Douglass[1] |

The Republic of Haiti is a small and impoverished nation located on Hispaniola island in the Caribbean. The island was originally populated by native Taino peoples, but Haiti is today populated mostly by the descendants of African slaves.[2] As is almost always the case in situation like this, the black population suffers systematic discrimination. Haiti's European diaspora and light-skinned mulatto population is very small, only about 5% of the population, but these people control most of the country's economic power.[3]

Europeans first showed up on Hispaniola during the first voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Columbus subsequently founded the first European fort in the Americas, La Navidad, on what is now the northeastern coast of Haiti. He also set about plundering the shit out of everything, beginning a process of brutal exploitation that led to the extermination of most of the native population and the massive importation of African slave labor to replace them. The entire island became part of Spain's colonial empire under the name "Santo Domingo", but France also wanted a foothold on the island. These competing claims were only settled in 1697, when Spain agreed to hand over the western half of Hispaniola as part of a concessions deal that ended the Nine Years' War.[4]

France named its new colony "Saint-Domingue", and used even more black slave labor to establish massive sugarcane plantations that generated enormous profit. In the midst of the French Revolution (1789–99), slaves and free people of color launched the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), led by a former slave and the first black general of the French Army, Toussaint Louverture. Despite their treachery and brutality, the French were unable to keep control of Haiti. Napoleon Bonaparte gave up on the island after his forces lost a decisive battle to Haitian leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who later went on to declare Haiti's independence and make himself its first president in 1804. Haiti was the second colonial nation to break free from its master, and it's the first and only country to have been established by a successful slave revolt.[5]

Unfortunately, Haiti's post-independence became an absolute shitshow. Haiti was saddled with massive debt owed to France, and it was ostracized by the international community, especially its large neighbor the United States. Grueling poverty contributed to political instability, which Haiti attempted to solve by invading the Dominican Republic in the 1870s. During this period, private and public investors from the United States became more entangled in Haiti's affairs. Further political problems in Haiti convinced US president Woodrow Wilson to invade the country in 1915. The US occupation was brutal, and it continued until 1934.

Following a series of short-lived presidencies, François 'Papa Doc' Duvalier took power in 1956, ushering in a long period of autocratic rule that was continued by his son Jean-Claude 'Baby Doc' Duvalier that lasted until 1986; the period was characterised by state-sanctioned violence against the opposition and civilians, corruption and economic stagnation. Since 1986 Haiti has been attempting to establish a more democratic political system, but that process was disastrously interrupted in 2004 when president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a leftist promoter of liberation theology, was allegedly overthrown by a US-orchestrated coup and kidnapped by US forces.[6] The US government denies that claim, but US denials have steadily lost credibility over the last few decades. For decades Haiti's elite has been going for the record for corruption levels, at the expense of the overwhelming majority of the population. If that wasn't enough, Haiti has also suffered a long string of natural disasters, including various hurricanes and a devastating earthquake in 2010 that killed between 100,000 and 300,000 people.[7]

Haiti has been in a state of political crisis since the end of 2022. There is high levels of rioting, gang violence, and hunger. There are zero remaining elected government officials, making Haiti a failed state. The US State Department maintains a Level 4 Travel Advisory against Haiti, warning of the extreme risk of crime, civil unrest, and kidnapping, and explaining that US officials are also prohibited to travel around Haiti in an unofficial capacity.[8]

Historical overview[edit]

Pre-Columbian history[edit]

“”They traded with us and gave us everything they had, with good will…they took great delight in pleasing us…They are very gentle and without knowledge of what is evil; nor do they murder or steal…Your highness may believe that in all the world there can be no better people…They love their neighbours as themselves, and they have the sweetest talk in the world, and are gentle and always laughing.

|

| —Christopher Columbus describing the natives of Hispaniola, 1492.[9] |

The island that is now called Hispaniola has been inhabited by humans since at least 5000 BCE.[10] The island was densely populated; by the Fifteenth Century, between 100,000 and several million Taino and Ciboney natives lived on the island, which the Taino called Quisqueya.[10] At the time of European arrival, the island was divided into five different Chiefdoms, which used natural features to delineate their territory in relation to each other.[11] The natives subsisted on meat and fish, and they used dugout canoes for transportation.[12]

As Columbus noticed when he arrived on Hispaniola, the Taino natives were also not colossal assholes like the Europeans were. Columbus described the Tainos as a physically tall, well-proportioned people, with a noble and kind personality.[9] This is likely due to their relative isolation; the Tainos had few external threats, and their chiefdoms tended to get along with each other.

Spanish rule[edit]

“”They tell us, these tyrants, that they adore a God of peace and equality, and yet they usurp our land and make us their slaves. They speak to us of an immortal soul and of their eternal rewards and punishments, and yet they rob our belongings, seduce our women, violate our daughters.

|

| —Spanish missionary Bartolomé de las Casas, quoting a Taino chief.[13] |

On Columbus’ second voyage, he started to forcibly extract tribute from the Taino in Hispaniola. Taino adults were expected to deliver either a thimble of gold or twenty-five pounds of spun cotton; failure to meet these demand would be punished by horrific dismemberment.[9] A Spanish soldier would cut off the hands of the Taino and leave them to bleed to death. The natives tried to resist the fucked-up treatment they received at the hands of the invaders. In one instance, allegedly 50,000 natives committed mass suicide to avoid further suffering at the hands of the Spanish.[14] Other groups of natives tried to revolt against the Spanish, with varying amounts of success.[9] The extent of the brutality is not entirely clear, since the goriest and most titillating accounts of violence come from Spanish chroniclers who had an obvious ax to grind against the Italian Columbus, but it was clear that things went south fast.[15]

If that's not bad enough, the Europeans also brought that old classic disease smallpox along for the ride, causing massive population losses among the natives.[16] Between epidemics, suicide, and slaughter, conditions were so bad that the Taino natives were effectively exterminated within a mere 25 years of Columbus' first voyage.[2]

The Spanish then introduced the encomienda system, which sought to regulate land and labor issues for the arriving Spanish colonists. Under this system, the Spanish Crown could award a monopoly on the labor of particular groups of indigenous peoples to a grant holder, called an encomiendo or encomiendero, who would then pass that title on to his descendants.[17] It was basically slavery, but under a different legal framework. The natives weren't technically owned by their Spanish masters, but they still had to follow his orders and they still suffered abuses. The Spanish colonists then forced the natives to grow cash crops instead of food and perform heavy labor.[18] The encomienda system was actually deadlier than traditional slavery, because individual natives were disposable as the system allowed Spanish masters to replace dead natives for free.[19]

The encomienda system also raises an important controversy regarding the extinction of the Taino. Until recently, most historians decided that the Taino died out mostly due to disease, no harm no foul. However, more analysis of primary sources has revealed that the truth is not so simple. In reality, the smallpox epidemic didn't arrive until quite some time after the Spanish began colonization, and the natives could have quite possibly recovered (like the Europeans did after the Black Death) were it not for the constant slavery and harsh conditions.[20]

In between murdering the natives, the Spanish also did some redecorating. Columbus named the island La Española, a name known to English-speakers as Hispaniola. He also built a series of forts and settlements, but the first permanent town established on the island was Santo Domingo.[21] It was named in honor of Saint Dominic, who was the founder of the Dominican Order. To govern the island, the Crown established the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, an office subordinate to the massive Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Having failed to find significant amounts of gold, the Spanish decided to focus on agriculture instead. Thus the introduction of sugarcane from the Canary Islands,[22] and the use of forced labor to cultivate it. After wiping out the natives, the Spanish started importing African slaves in order to maintain their labor force.

Once the sugar trade was established, Spain turned its attention elsewhere, allowing Hispaniola to be lost within the empire's byzantine bureaucracy.[23] Agriculture was disorganized under Spain, and the island's production never met its potential during this period.

Due to the nature of trade winds, however, Hispaniola remained an important location, serving as the effective gateway to the Caribbean. As a result of this importance combined with Spain's neglect, Hispaniola became a hotbed of privateers, most notoriously Sir Francis Drake of England.[24] Encroachments by other European powers gradually reduced Spanish dominance in the Caribbean.

French rule[edit]

Most significant of the other European powers encroaching on Hispaniola was France. French colonists arrived in what is now Haiti in 1664 under the banner of the French West India Company.[25] Settlers steadily encroached upon the northwest shoulder of the island, and they took advantage of the area's relative remoteness from the Spanish capital city of Santo Domingo. In 1670 they established their first major community, Cap François (later Cap Français, now Cap-Haïtien).[25]

Meanwhile, Europe blew up for the upteenth time in 1688, this time as a result of the expansionist policies of Louis XIV of France. France alone had to stand against an alliance of the Netherlands, England, and the Hapsburg rulers of Spain and Austria.[26] The alliances were lopsided, but France was not a force to be fucked with. In 1688, the French army and navy were both more powerful by far than any of their nearest rivals. France generally won the ensuing conflicts, but economic problems forced Louis to make peace in 1697.[27] A lot of land traded hands in the subsequent negotiations, and Spain agreed to give Haiti to France.

France named their new colony Saint-Domingue, the French equivalent of Santo Domingo. Even moreso than the Spanish, the French imported massive numbers of slaves to work on plantations. By the eve of the French Revolution, Saint-Domingue produced about 60 percent of the world's coffee and about 40 percent of the sugar imported by France and Britain.[28] During this period, it was by far France's most important colonial possession.[29] Meanwhile, industrial agriculture devastated Haiti's ecosystem, with deforestation causing erosion and unwise planting decisions causing soil exhaustion.[29]

The industrial demand for slave labor meant that slaves vastly outnumbered the white French colonists. In 1788, the French census counted 25,000 whites and 700,000 slaves.[30] Of course, none of the slaves really lived long enough to take advantage of that numbers advantage. French landowners treated their slaves atrociously, and an unknowable number of slaves perished from malnutrition, exposure, and disease.[29] This was economics; it was cheaper to import new slaves than it was to improve living conditions for the slaves they already had.[31]

Death rates for slaves in Haiti were higher than anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere.[32] Life expectancy for slaves was just 21 years.[33] In total, French rule in Haiti killed about a million black slaves; many thousands chose suicide over suffering.[34] Torture of slaves was routine; they were whipped, burned, buried alive, restrained and allowed to be bitten by swarms of insects, mutilated, raped, and had limbs lopped off.[35] Slaves caught eating sugarcane had to wear muzzles. The Catholic Church condoned these atrocities, arguing that slavery was the best way to convert the Africans to Christianity.[36]

The slaves resisted, of course. Poisoning was the most common method, deployed against landowners, their families, and their livestock.[37] Slaves also burnt down buildings and fields. Resistance among the slave population continued to grow, eventually culminating in revolution.

Haitian Revolution[edit]

“”From their French masters, [the slaves] had known rape, torture, degradation, and, at the slightest provocation, death. They returned in kind. For two centuries the higher civilization had shown them that power was used for wreaking your will on those whom you controlled. Now that they held power they did as they had been taught.

|

| —C. L. R. James, Trinidadian historian.[38] |

France, of course, blew up into revolution in 1789. While the French were preaching Enlightenment ideals, the black Haitians started wondering why none of those highbrow ideals applied to them. The slaves drew up a list of demands for the French, and these demands were initially quite limited. As Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot wrote, "In one of their earliest negotiations with representatives of the French government, the leaders of the rebellion did not ask for an abstractly couched 'freedom.' Rather, their most sweeping demands included three days a week to work on their own gardens and the elimination of the whip."[38] It actually seemed like the French revolutionary government was going to grant these demands, but the white planters actually living in Haiti decisively refused.[39]

Having ruled out a peaceful compromise, the enslaved revolted across Haiti in 1791 under the leadership of former slave Toussaint Louverture. From the beginning, the slave revolution was marked with extreme violence from both sides. The French used ruthless measures to put down the revolt, and the slave armies responded by completely burning down multiple large Haitian cities.[40] French planters organized militias and struck back; their initial operations in 1791 killed about 15,000 blacks.[39] The former slaves sought revenge against their former masters by raping and killing thousands of white people, combatant and civilian alike.[39]

The situation was complicated by the outset of the French Revolutionary Wars. When the British tried invading Haiti, the slaves briefly allied with them and then the Spanish.[40] Eventually, the old French regime fell to internal pressures, and the new government abolished slavery in 1793. However, Toussaint Louverture was no fool, and he knew that the black Haitians would never be free unless they had the right to their own land.[40] Louverture thus paid lip service to the French while pursuing his own goals.[41] He invaded Santo Domingo, the Spanish half of Hispaniola, and in 1801 he had himself declared "governor-general for life".

Louverture also started rebuilding Haiti's economy. He reopened commercial relations with the U.S. and Britain, restored destroyed sugar and coffee estates to operating condition, and halted the wide-scale massacres of white people.[40] Unfortunately for him, Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in France. Bonaparte wanted to maintain France's empire in the Americas, and to do that he felt that he needed to put down the slave rebellion in Haiti. To that end, he sent his brother-in-law Charles Leclerc with a massive army to attack Louverture in 1802. The slaves responded with scorched-earth tactics. Louverture wrote to his subordinates, "Do not forget... that we have no other resource than destruction and fire. Bear in mind that the soil bathed with our sweat must not furnish our enemies with the smallest sustenance. Tear up the roads with shot; throw corpses and horses into all the foundations, burn and annihilate everything in order that those who have come to reduce us to slavery may have before their eyes the image of the hell which they deserve".[42] Leclerc was shocked, having expected the slaves to return to their chains. Instead, both sides fought a desperate campaign. Soldiers from Poland, who had been attached to the French army by Napoleon, actually defected to the Haitians' side due to maltreatment by the French and sympathy towards the Haitians as a fellow oppressed population; some of their descendants![]() (plus a few Polish immigrants who've come since) still reside in Haiti.[43]

(plus a few Polish immigrants who've come since) still reside in Haiti.[43]

Louverture's forces eventually began to fail against the more powerful French forces, and he sued for a cease-fire. That he got, but Leclerc betrayed the terms of the treaty and tricked Louverture into getting arrested.[40] Louverture died in a French prison. Throughout the countryside, guerrilla warfare continued and the French staged mass executions via firing squads, hanging, and drowning Haitians in bags. General Donatien de Rochambeau, the son of the one who served in the American Revolution, invented a new means of mass execution, which he called "fumigational-sulphurous baths": killing hundreds of Haitians in the holds of ships by burning sulfur to make sulfur dioxide to gas them.[39]

That wasn't the end of things, though. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of l’Overture’s generals and himself a former slave, took charge of the revolution and led the former slaves to victory in a decisive battle against the French.[44] With Poles fighting against the French and the French dying of yellow fever,[40] France eventually had no choice but to abandon the campaign.

The revolution won. In 1804, Saint-Domingue adopted a new constitution and became Haiti. Dessalines, who was less forgiving than Louverture,[45] then decided to resume the massacres against White Haitians![]() , which not only extinguished any chance of internal stability, but also created the go-to excuse for US slaveowners opposing slavery abolishment.[46] He nevertheless rewarded his Polish allies, guaranteeing citizenship to those Poles that wished to stay and calling them the "white negroes of Europe".[43][47] The town of Cazale is to this day a Polish-majority community in Haiti. Dessalines created the Haitian flag in 1803, whose colors represent the alliance of blacks and mulattoes against whites.[40]

, which not only extinguished any chance of internal stability, but also created the go-to excuse for US slaveowners opposing slavery abolishment.[46] He nevertheless rewarded his Polish allies, guaranteeing citizenship to those Poles that wished to stay and calling them the "white negroes of Europe".[43][47] The town of Cazale is to this day a Polish-majority community in Haiti. Dessalines created the Haitian flag in 1803, whose colors represent the alliance of blacks and mulattoes against whites.[40]

Forced isolation and debt[edit]

“”The Haitians were forced to destroy the entire colonial socioeconomic structure that was the raison d'etre for their imperial importance; and in destroying the institution of slavery, they unwittingly agreed to terminate their connection to the entire international superstructure that perpetuated slavery and the plantation economy. That was an incalculable price for freedom and independence.

|

| —Franklin Knight, US historian.[40] |

After Haiti's victory and independence, most of the island's remaining French population fled to places like Cuba, Jamaica, or Louisiana along with any slaves who remained loyal or were kidnapped.[40] Haiti's mere existence caused consternation among the powers of Europe, as its revolution inspired talk of other revolts in the Caribbean. The rest of the world turned its back on Haiti.

France refused to acknowledge Haiti's independence until 1825. When it finally did recognize Haiti, French King Charles X demanded that Haiti pay an "independence debt" to compensate former colonists for the slaves who had won their freedom.[48] French warships stationed off Haiti's coasts backed up that demand. Under the threat of a renewed invasion and reenslavement, Haiti agreed to accept the burden of paying 150 million gold francs to its former oppressor.[48] That amount was more than ten times Haiti's annual revenue, so Haiti was also saddled with ridiculous interest rates which ensured that it could never escape that debt. By 1900, Haiti was spending 80% of its domestic product on debt payments.[33] Even worse, the debt was completely illegal. When the original indemnity was imposed by the French king, the slave trade was technically illegal; such a transaction – exchanging cash for human lives valued as slave labor – represented a gross violation of both French and international laws.[48] Despite that fact, Haiti was stuck paying much of its income to France until 1947, ensuring that it would remain in harsh poverty.

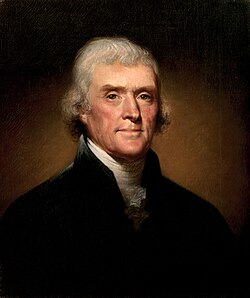

Just as shamefully, the United States turned away from Haiti despite the fledgling black nation's similar history. When the slave revolt first began, the United States actually aided the French against the slaves.[49] There was hope, however, as incoming US president John Adams was resolutely anti-slavery, and he reversed course to aid Louverture's revolution.[49] Adams was a one-term president, though, and his successor was Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was himself a Virginia slaveholder, and his policy towards Haiti was extremely hostile. He refused to recognize the nation's independence, and he imposed a trade embargo against Haiti.[49] The US didn't start trading with Haiti again until the 1820s, and it didn't officially recognize Haiti until 1862, after the Southern states had left the US during the American Civil War.[50] All of this amounts to a monstrous ingratitude, as Napoleon's defeat in Haiti convinced him to sell off the entirety of the Louisiana Purchase to the United States.[51]

Crises, humiliation, and wars[edit]

Jean-Jacques Dessalines made himself into a dictator, styling himself emperor just like his old enemy Napoleon.[52] After Dessalines' assassination Haiti became split into two, with the Kingdom of Haiti in the north directed by Henri Christophe, later declaring himself Henri I, and a republic in the south centered on Port-au-Prince, directed by Alexandre Pétion.[53] The Haitian Republic involved itself in other revolutions in Latin America, including sending military aid and volunteers to Simon Bolivar.[54] Eventually, the Republic managed to unify Haiti after the collapse of the Kingdom's government, but the experience of being disunited helped convince many Haitians that it was time to unite the entire island of Hispaniola.

In 1822, Haiti invaded the newly-independent Dominican Republic and conquered it successfully. The subsequent 22-year occupation would result not only in the economic and cultural deterioration of of the entire island but also in the fostering of extreme hatred towards Haiti by the Dominicans.[55] The Haitians redistributed land in Santo Domingo to their own people, and confiscated property from the Catholic Church. That latter bit especially pissed off the Dominicans, most of whom were pious Catholics.[55] On a positive note, however, the Haitians did liberate the black slaves in Santo Domingo. Dominicans resisted the occupying Haitian force, and they began the Dominican War of Independence in 1844.[56] The conflict did not truly come to an end until 1856, after the Haitians had tried multiple times to reassert their rule.

This loss destabilized Haiti's politics again, with the country seeing a second imperial regime rise and fall. Meanwhile, the US and Europe started to remember Haiti's existence. In 1889, the United States tried to use gunboat diplomacy to acquire a naval port in Haiti, sending thousands of Marines to intimidate Haiti's government.[57] The scheme fell through due to the non-cooperation of Frederick Douglass, who had been appointed commissioner to Haiti by previous president Ulysses S. Grant. In 1897, the German Empire decided to take a shot at Haiti. German national Emile Lüders beat up a Haitian police officer to defend a criminal, and the German government sent two warships to embarrassingly extract compensation payments, a letter of apology to the German government, and a 21-gun salute to the German flag.[58] To top the shit cake with a middle finger, the Germans also made the Haitian president raise a white flag over his palace as a symbol of surrender. That destabilized Haiti's politics once more, and various succeeding presidents fell to coups or assassinations.

US invasion and occupation[edit]

“”Military camps have been built throughout the island. The property of natives has been taken for military use. Haitians carrying a gun were for a time shot on sight. Machine guns have been turned on crowds of unarmed natives, and United States Marines have, by accounts which several of them gave me in casual conversation, not troubled to investigate how many were killed or wounded.

|

| —NAACP executive secretary Herbert J. Seligman, 1920.[59] |

As European powers encroached in Haiti's internal affairs, the US started to get jealous. The US especially considered Germany as its chief rival for influence in Haiti, as German merchants traded extensively there and German immigrants started marrying into the Haitian population.[60] Fearing that chaos in Haiti would create an opportunity for Europeans to expand their economic interests there at America's expense, Woodrow Wilson used the 1915 assassination of Haiti's president as an excuse to order the United States Marines to invade the country.[61]

Things went sour for Haiti very quickly after that. US Marines took over the capital and censored Haiti's press, then imposed a new constitution on Haiti which granted foreigners (meaning US businessmen) the right to own land and capital in Haiti.[62] Haiti's legislature and citizenry bitterly opposed this measure, but it's not like the US gave a shit what black people thought; marines, at that time, were disproportionately whites from the South, which went about as well as one might expect. Then the US seized Haiti's gold reserves (Christopher Columbus would have been jealous) and started collecting taxes from the Haitian population to pay Haiti's foreign debts to the US and France.[63] The Haitians weren't happy about that either, so the US decided to install a puppet president to make things seem legitimate. Said puppet then dissolved the legislature to prevent them from objecting.

U.S. occupiers re-instituted a system known as civil conscription (impressed labor), in which Haitian civilians were captured and forced to work on public projects, such as building roads, and established the National Guards.[59] They also instituted segregation policies, which were the norm in the US at the time.[64]

Opposition to the U.S. occupation began immediately, and the Haitians received military aid from the Germans.[59] During the occupation, US Marines killed 15,000 Haitians in their attempts to brutally suppress resistance.[61] The occupation frequently featured indiscriminate murders, robberies, and massacres perpetrated by American marines.[65] After killing a prominent Haitian rebel, the US Marines circulated the image of his corpse as a warning, but they only succeeded in turning him into a martyr.[66]

Eventually, US president Herbert Hoover started to question the necessity and impact of the occupation, and the investigatory commission he appointed criticized the lack of rights and political power allowed to native Haitians.[67] Hoover lost the presidency to Franklin D. Roosevelt, who began a full withdrawal in 1934. Sadly, the US still fully controlled Haiti's finances until 1947.[68]

Garde era[edit]

During the US occupation, they created and trained the Garde d'Haïti to enforce America's will on the Haitians.[69] Although the Garde was manned mostly by blacks, its officers were exclusively white or mulatto.[70] In the wake of the US departure, Haitian president Sténio Vincent started to become increasingly dictatorial, and he eventually used the Garde to seize control of Haiti's government. He rewrote Haiti's constitution again, this time granting himself the power to dissolve the legislature at will, to reorganize the judiciary, to appoint ten of twenty-one senators, and to rule by decree.[70] He also started using the Garde as his personal attack dogs, censoring the press and killing his opposition.

Despite having a powerful military, Haiti's leaders didn't seem to care enough to use it. Also in the wake of the US withdrawal, Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo used anti-Haitian hatred as a propaganda tool. In a 1937 event know known as the Parsley massacre![]() , he ordered his military onto the border with Haiti to indiscriminately murder any Haitians who lived to close to it.[71] Dominican soldiers killed an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 Haitians, who were bludgeoned and bayonetted, then herded into the sea, where sharks finished them off.[72][73] Instead of responding to that outrage, Vincent decided that the Garde were planning a coup against him on Trujillo's behalf, so he purged the Garde's ranks of anyone he didn't like.[70]

, he ordered his military onto the border with Haiti to indiscriminately murder any Haitians who lived to close to it.[71] Dominican soldiers killed an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 Haitians, who were bludgeoned and bayonetted, then herded into the sea, where sharks finished them off.[72][73] Instead of responding to that outrage, Vincent decided that the Garde were planning a coup against him on Trujillo's behalf, so he purged the Garde's ranks of anyone he didn't like.[70]

After about a decade of not giving a shit, the US showed up again in 1941 to tell President Vincent to cut it out. Vincent caved, and he resigned his office to be replaced by Elie Lescot. Lescot proved to be no different from his predecessor, using the Garde to threaten the legislature into granting him the same broad powers Vincent had.[70] Lescot realized that he had to justify these extreme measures, so he declared war on the Axis alongside the US and used the war as an excuse for his actions. Haiti, however, played no role in the war except for supplying the United States with raw materials and serving as a base for a United States Coast Guard detachment.[70]

Lescot's downfall came when it became known that he was a personal friend of Rafael Trujillo; Lescot had been bribed by the Dominican repeatedly. The Garde reacted negatively to this news, and they overthrew Lescot in 1946.[70] Haiti was effectively a dictatorship at this point, and several abortive attempts at democracy threw the country into turmoil between 1950 and 1956. In 1957, smoky backroom deals led to former labor minister François Duvalier becoming the favored candidate for Haiti's leadership. He won that election.

The Duvaliers[edit]

François[edit]

Emboldened by his popularity, "Papa Doc", as his supporters called him, reorganized Haiti's legislature and declared himself president for life in 1964.[74] Having witnessed the tumultuous Garde era, Duvalier decided that he didn't trust the military. Duvalier created a Presidential Guard to serve as his personal army, and he then purged most of the military's officers.[74] He then started to outright replace the military with a peasant militia called the Volunteers for National Security (Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale) or VSN. They essentially became Duvalier's secret police force, rooting out dissenters and killing them. Corruption—in the form of government rake-offs of industries, bribery, extortion of domestic businesses, and stolen government funds—enriched the dictator's closest supporters.[74]

Duvalier also created a cult of personality for himself by practicing voodoo and identifying himself with legendary figure Baron Samedi.[75] He also claimed to be God, because at this point why not? Despite his bizarre and brutal behavior, Duvalier was a tolerated US ally. Duvalier was many things, but he wasn't a gawddamn communist, and the US wasn't about to tolerate a pro-leftist government in the Caribbean when they already had to deal with Cuba.[74] In total, the Papa Doc regime murdered about 30,000 Haitians.[74]

Jean-Claude[edit]

In 1971 Duvalier died, and he was succeeded by his son Jean-Claude Duvalier, nicknamed "Baby Doc", who was an idiot teenager when he first came to power. Thus, Baby Doc took a hands-off approach towards governance, by which we mean he ignored actual work in favor of stealing from the treasury.[76] We call this style of rulership a kleptocracy. While Baby Duvalier was too busy pilfering funds, the Haitian public was ravaged by multiple plagues, including AIDS and African Swine Fever. Duvalier then held an extravagant wedding for himself, which cost $3 million, which was a remarkably tone-deaf thing to do in the middle of multiple crises and endemic poverty.[76] Duvalier had married into the rich mulatto Bennett family, which created even more problems for himself. Popular discontent intensified in response to increased corruption among the Duvaliers and the Bennetts, as well as the repulsive nature of the Bennetts' dealings, which included selling Haitian cadavers to foreign medical schools and trafficking in narcotics.[76] The last straw came when Baby Doc was dissed by Pope John Paul II, who called for a more equitable distribution of income, a more egalitarian social structure, and for the elites to actually give a shit about the lives of the people.[76]

Revolts began in 1986, and the alarmed Ronald Reagan pressured Duvalier into giving up power. Duvalier agreed, but then did a "takesie-backsie", pissing off just about everyone and triggering widespread rioting and military disobedience that forced him out of power.[76] Duvalier went into exile in France, because France sucks ass in this article.

Brief ray of hope, snuffed out by the US[edit]

Haiti was an absolute dumpster fire after Duvalier left, suffering a series of fraudulent elections, and two coups in 1988[77] and 1991.[78] Haiti just couldn't catch a fucking break. Finally, the 1990 elections brought in the first Haitian politician since its independence who gave a shit about anything other than himself. This guy's name was Jean-Bertrand Aristide, and he had been a leader of the pro-democracy movement that fought the Duvaliers and was a prominent proponent of liberation theology.[79]

Aristide immediately set about trying to reform Haiti. He sought to bring the military under civilian control, initiated investigations of human rights violations, and began several anti-corruption programs.[79] Surprise, surprise, Haiti's military officers and business elites hated his guts. Just as unsurprisingly, the military then ousted Aristide in a 1991 coup, forcing him into exile and establishing an unelected junta in his place. At this point, however, the US did something good. In 1994, US President Bill Clinton ordered the US Marines into Haiti again, this time to threaten the military dictatorship into relinquishing power and returning authority to the democratically-elected Aristide.[80] Unfortunately, this lone good action by the US came with a price. In order to get US help, Aristide had to promise to implement free market reforms to Haiti which sabotaged his economic recovery programs and prevented him from addressing widespread inequality.[81]

From that point onward, Haiti effectively became a Clinton family vanity project. The Clintons poured money into the country in the hopes of building infrastructure and attracting investors; these efforts failed due to mismanagement and were quietly abandoned in the 2010s.[82] As US economist Antony Loewenstein wrote, "The neoliberal, exploitative economic model currently being imposed [on Haiti] has failed many times before."[82]

Aristide played ball for the US for a little while, but he eventually decided to return to his leftist roots in the hopes that he could salvage his country. Under his rule Haiti built schools, mandated education funding, enacted a literacy program that reached 320,000 people, doubled the minimum wage, built health clinics to combat AIDS, punished tax evasion by the elites, and disbanded the corrupt military.[83] As we said above, Aristide was basically the first Haitian leader who actually gave a shit. Then, almost out of nowhere in 2004, a wave of murder and rapes targeted his government officials and instigated riots, and then Aristide was compelled to leave by US security forces.[84] The incoming president asked for an international intervention, and the US sent about 1,000 Marines to occupy Haiti's capital.

The University of Miami's School of Law sent observers to conduct a human rights investigation and came up with the following conclusion:[84]

“”U.S. officials blame the crisis on armed gangs in the poor neighborhoods, not the official abuses and atrocities, nor the unconstitutional ouster of the elected president. Their support for the interim government is not surprising, as top officials, including the Minister of Justice, worked for U.S. government projects that undermined their elected predecessors. Coupled with the U.S. government’s development assistance embargo from 2000–2004, the projects suggest a disturbing pattern.

|

Meanwhile, Aristide alleges that the US removed him, having effectively sent Marines to kidnap him and his wife.[6] The US denies that claim, but who you believe depends on whether you trust the word of Aristide or Dick Cheney.[85]

Today[edit]

Long story short, Haiti fell into disarray after Aristide's downfall. Haiti's currency plunged, the price of gasoline and kerosene (used for lamps and cooking in most Haitian homes) has soared, food insecurity has spiked, and the most recent former president, Jovenel Moïse, ruled by decree and engaged in blatant theft from public projects.[83] In July of 2021, Moise was assassinated in his home by gunmen, inflicting yet more political chaos on the beleaguered state.[86] Worse, in a turn of events likely to worry anyone who's watched Babylon 5![]() , there is compelling evidence that acting president and prime minister Ariel Henry, appointed as the latter just before Moise's assassination but not sworn in prior, was involved in the assassination.[87] In June 2024, A

, there is compelling evidence that acting president and prime minister Ariel Henry, appointed as the latter just before Moise's assassination but not sworn in prior, was involved in the assassination.[87] In June 2024, A United States backed Kenya-led security intervention of 400 Kenyan police officers were sent to Haiti.

Haiti has been repeatedly hammered by crises, such as hurricanes![]() and earthquakes

and earthquakes![]() . And that's what Haiti is known for now. Once a revolutionary black republic, Haiti has been transformed by corrupt leaders and an exploitative international community into a simple dumping ground for international aid packages. What a shame. What a goddamn shame.

. And that's what Haiti is known for now. Once a revolutionary black republic, Haiti has been transformed by corrupt leaders and an exploitative international community into a simple dumping ground for international aid packages. What a shame. What a goddamn shame.

Human rights[edit]

Violence and terrorism[edit]

Apparently emboldened in the wave of violence that ousted Aristide, criminals and corrupt officials run rampant. Looting, kidnappings, arson, rape, and murder are endemic.[83] Many media sources blame this on "gang violence". The reality is much more frightening. The Haitian government and its US-trained police force actively enable and mobilize organized crime in order to target suspected opposition.[83] In effect, the Haitian government wields death squads that operate with complete impunity. Want an example? No? Too bad! In 2018, the government sent the Nan Chabon gang into the La Saline neighborhood, which was known to be a focal organizing point for the democratic opposition.[88] That was about 60 people beaten and raped to death.

In February 2020, Haitian police refused to protect another opposition neighborhood. The government had offered to bribe the neighborhood's leaders to stop protests.[83] Shortly after they refused, dozens of armed men opened fire in the area with rifles and burned homes and cars as part of a three-day rampage.[89] We know for sure that at least three people died, but the actual number is almost certainly much higher.

As of 2024; gangs control more than 80% of the Haitian capital city Port-au-Prince and death tolls continuing to increase as Haiti’s corrupt government further deteriorates and endures political instability.[90][91][92]

Gender and sexual orientation[edit]

Haiti has no specific laws against domestic violence, sexual harassment, or other forms of violence targeted at women and girls.[93] Rape was only explicitly criminalized in 2005, and it's still almost never prosecuted or even investigated.[94] Abortion is illegal in all circumstances, including in cases of sexual violence.[93] If a wife commits adultery, Haitian law excuses husbands for murdering them.[95] Women do not have the same right in the reverse situation.

LGBT individuals still suffer high levels of discrimination. Gay marriages are not recognized, and LGBT individuals face harassment by police and authorities.[96] In 2017, the Haitian Senate passed two anti-LGBT bills, which are still working their way through the Haitian legislature. One bill calls for a ban on same-sex marriage, as well as any public support or advocacy for LGBT rights. Should the ban become law, "the parties, co-parties and accomplices" of a same-sex marriage could be punished by three years in prison and a fine of about US$8,000.[93] That's a shitload of money, even in the US. Incomes are much lower in Haiti.

Environment[edit]

Deforestation[edit]

One of Haiti's most infamous problems is deforestation, but it's widely misunderstood by the global public. The prevailing narrative is that Haiti's trees are disappearing due to overpopulation, poverty, and Haiti's charcoal industry.[97] After telling that story, people presumably then inwardly roll their eyes at the ignorance of those poor dumb blacks. The reality is far, far different.

Deforestation began a long time ago, starting under the Spanish and massively accelerating under the French. The French were especially effective at clearing out forests as they were constantly building sugarcane plantations, slave cabins, and fancy houses for the rich whites.[97] Luckily for Haiti, black slaves kicked the French out on their baguette asses in 1804. Unfortunately for Haiti, the French showed up again with a bunch of warships to threaten debt payments out of the fledgling nation. In order to make those payments, Haiti had to outsource many of its natural resources. Including and especially trees. Haiti sold off its mahogany forests, which foreign firms proceeded to raze, process, and ship overseas to be made into fancy furniture.[97]

That's all nice if you're a Nineteenth Century gentleman shopping for a dresser, but it sucks ass for the people who actually have to live in Haiti. Trees, after all, are good at holding soil in place and drinking up rainwater. Without trees, you start to see flooding and landslides. Hundreds of thousands of Haitians die each year in flood or landslide events related to deforestation.[98] Thus, colonial destruction of Haiti's forests is big part of why earthquakes and hurricanes are so deadly.

So why aren't reforestation efforts working? You see, the UN and USAID came up with the brilliant idea to encourage farmers and peasants to plant trees. The problem was that those trees then become the property of the Haitian government, which most Haitians hate and which couldn't possibly give less of a shit about the environment.[97] The good thing is that the international community caught on to this, although only relatively recently. The other good news is that Haiti is urbanizing, which is giving trees the chance to regrow.[97] The bad news is that Haiti is still the target of foreign predators and is still run by an awful government. You win some, you lose some. In Haiti, you mostly lose some.

Gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

- Toussaint Louverture, the best-known leader of the Haitian Revolution

- Liberia

- Navassa Island, currently disputed between the United States and Haiti

External links[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ "The Nation's Problem" - a lecture given to the 1890 Abolitionist Reunion in Boston

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Haiti. CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ Lobb, John (2018). "Caste and Class in Haiti". American Journal of Sociology. 46 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1086/218523. JSTOR 2769747.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Peace of Ryswick.

- ↑ Danticat, Edwidge (2005). Anacaona, Golden Flower. Journal of Haitian Studies. 11. New York: Scholastic Inc. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-0-439-49906-4. JSTOR 41715319.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Aristide says U.S. deposed him in 'coup d'etat'. CNN.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on 2010 Haiti earthquake.

- ↑ Haiti Travel Advisory. US State Department.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Taíno: Indigenous Caribbeans. Black History 365.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Haiti. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Chiefdoms of Hispaniola.

- ↑ Arawak/Taino Native Americans. Webster.

- ↑ Abbot, E. (2010). Sugar: A Bittersweet History. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59020-772-7.

- ↑ 9 reasons Christopher Columbus was a murderer, tyrant, and scoundrel. Vox.

- ↑ The Black Legend Revisited: Assumptions and Realities

- ↑ Koplow, David A. (2004). Smallpox: The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24220-3.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Encomienda.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. 1. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-313-33272-2.

- ↑ Yeager, Timothy J. (December 1995). "Encomienda or Slavery? The Spanish Crown's Choice of Labor Organization in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America". The Journal of Economic History. 55 (4): 842–859. doi:10.1017/S0022050700042182. JSTOR 2123819.

- ↑ The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history. LA Times.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Santo Domingo.

- ↑ Sugar Cane: Past and Present. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. Archived.

- ↑ Haiti: Spanish Discovery and Colonization. Country Studies.

- ↑ Haiti: French Colonialism. Country Studies.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 French Settlement and Sovereignty. Country Studies.

- ↑ War of the Grand Alliance. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Nine Years' War.

- ↑ Colonial Society. Country Studies.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Haiti. Britannica.

- ↑ Coupeau, Steeve (2008). The History of Haiti. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-313-34089-5.

- ↑ Abbott, E. (2011). Haiti: A Shattered Nation. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4683-0160-1. p. 26–27.

- ↑ Rodriguez, J.P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33272-2. p. 229.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Haiti: a long descent to hell. The Guardian.

- ↑ Abbott, E. (2011). Haiti: A Shattered Nation. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4683-0160-1. p. 27

- ↑ Abbott, E. (2011). Haiti: A Shattered Nation. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4683-0160-1. p. 26–27

- ↑ Ferguson, J. (1988). Papa Doc, Baby Doc: Haiti and the Duvaliers. John Wiley & Sons, Limited. ISBN 978-0-631-16579-8 p. 3.

- ↑ Reinhardt, C.A. (2008). Claims to Memory: Beyond Slavery and Emancipation in the French Caribbean. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-412-8. p. 61.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Haitian Revolution. Wikiquote.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 See the Wikipedia article on Haitian Revolution.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 40.7 40.8 The Haitian Revolution: History of a Successful Slave Revolt. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ Haitian Revolution. Britannica.

- ↑ Perry, James (2005). Arrogant Armies: Great Military Disasters and the Generals Behind Them. Edison: CastleBooks. p. 80

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Polish patriots once fought alongside rebelling slaves. Where is that solidarity today? | opinion. Newsweek.

- ↑ Haitian Revolution. Black Past.

- ↑ Louverture had had a tolerant master, while Dessalines had been a field slave.

- ↑ Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South; Stephanie McCurry; pages 12-13

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Polish Haitians.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 France's debt of dishonour to Haiti. The Guardian.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 The United States and the Haitian Revolution, 1791–1804. US State Department Office of the Historian.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on United States and the Haitian Revolution.

- ↑ The Bittersweet Victory at Saint-Domingue. Slate.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on First Empire of Haiti.

- ↑ Peguero, Valentina (November 1998). "Teaching the Haitian Revolution: Its Place in Western and Modern World History". The History Teacher. 32 (1): 33–41. doi:10.2307/494418. JSTOR 494418.

- ↑ Bushnell, David; Lester Langley, eds. (2008). Simón Bolívar: essays on the life and legacy of the liberator. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7425-5619-5.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 HAITIAN INVASIONS AND OCCUPATION OF SANTO DOMINGO (1801-1844). Black Past.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Dominican War of Independence.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Môle Saint-Nicolas affair.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Lüders affair.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 See the Wikipedia article on United States occupation of Haiti.

- ↑ U.S. Invasion and Occupation of Haiti, 1915-34. US State Department Archive.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 The Long Legacy of Occupation in Haiti. Edwidge Danticat. The New Yorker. July 28, 2015.

- ↑ Hans Schmidt (1971). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. Rutgers University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780813522036.

- ↑ Weinstein, Brian and Aaron Segal (1984). Haiti: Political Failures, Cultural Successes (February 15, 1984 ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 175. ISBN 0-275-91291-4. p. 29

- ↑ 100 years ago, the U.S. invaded and occupied this country. Can you name it? Ishaan Tharoor. Washington Post. July 30, 2015.

- ↑ The Conquest of Haiti Selections from The Nation magazine 1865-1990 edited by Katerina Vanden Heuvel. Thunder's Mouth Press, 1990, paper.

- ↑ An Iconic Image of Haitian Liberty. The New YorkerJuly 28, 2015.

- ↑ Musicant, I, The Banana Wars, 1990, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., ISBN 0025882104 p. 232–233

- ↑ Schmidt, Hans. The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. (232)

- ↑ Haiti: US Occupation. Country Studies.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 70.4 70.5 Haiti: Politics and the Military. Country Studies.

- ↑ Farmer, Paul (2006). AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. California University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-520-24839-7.

- ↑ Malone, David (1998). Decision-making in the UN Security Council: The Case of Haiti, 1990–1997. ISBN 978-0-19-829483-2.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Parsley massacre.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 François Duvalier. Country Studies.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on François Duvalier.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 76.4 Jean-Claude Duvalier. Country Studies.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on June 1988 Haitian coup d'état.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on 1991 Haitian coup d'état.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 See the Wikipedia article on Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Operation Uphold Democracy.

- ↑ Bell, Beverly (2013). Fault Lines: Views across Haiti's Divide. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 30–38. ISBN 978-0-8014-7769-0.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Haiti and the failed promise of US aid. The Guardian.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 83.4 The Final Chapter Has Still Not Been Written: Remembering The 2004 Coup in Haiti. Counterpunch.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 See the Wikipedia article on 2004 Haitian coup d'état.

- ↑ US says Aristide not forced out. The Irish Times.

- ↑ Official: Haiti President Jovenel Moïse assassinated at home. Associated Press.

- ↑ Haitian Prime Minister involved in planning the President’s assassination, says judge who oversaw case. CNN.

- ↑ "Haiti government complicit in La Saline Massacre". HaitiAction.net

- ↑ UN report questions police, highlights violence in Haiti. Associated Press.

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-68531759

- ↑ https://time.com/7000221/haiti-port-au-prince-gang-war/

- ↑ https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/haitis-death-toll-rises-international-support-lags-un-report-says-2024-04-19/]

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 Haiti: Events of 2019. Human Rights Watch.

- ↑ Haiti’s Silenced Victims. New York Times.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Human rights in Haiti.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on LGBT rights in Haiti.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 97.3 97.4 One of the most repeated facts about Haiti is a lie. Vice.

- ↑ IF CURRENT DEFORESTATION RATES CONTINUE, HAITI MAY LOSE ITS FORESTS WITHIN TWO DECADES. Pacific Standard.