French colonial empire

“”The very flatness of the staged colonial postcards, with their plain descriptions of a foreign place and its people, persuaded French viewers of the photographs' authenticity. But they were not plain descriptions; they were designed to convince those living in France that Algeria and its topless, trapped women were better off being colonized.

|

| —Sarah Sentilles, historian[1] |

| The white man's burden Imperialism |

| The empires strike back |

| Veni, vidi, vici |

“”First we must study how colonization works to decivilize the colonizer, to brutalize him in the true sense of the word, to degrade him, to awaken him to buried instincts, to covetousness, violence, race hatred, and moral relativism; and we must show that each time a head is cut off or an eye put out in Vietnam and in France they accept the fact, each time a little girl is raped and in France they accept the fact, each time a Madagascan is tortured and in France they accept the fact… a universal regression takes place, a gangrene sets in, a center of infection begins to spread; and that at the end of all these treaties that have been violated, all these lies that have been propagated, all these punitive expeditions that have been tolerated, all these prisoners who have been tied up and interrogated, all these patriots who have been tortured, at the end of all the racial pride that has been encouraged, all the boastfulness that has been displayed, a poison has been instilled into the veins of Europe and, slowly but surely, the continent proceeds toward savagery.

|

| —Aimé Césaire, French poet, author, and politician from Martinique, writing in Discourse on Colonialism (1950)[2] |

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the French colonial empire comprised the second-largest collection of colonies in the world, ranking behind only the British Empire. It consisted of a series of colonies, protectorates,[3] and (from 1919) League of Nations mandates which were administered by various governments of France. Many historians make a distinction between the "first" and "second" French colonial empires because most French colonies prior to about 1830 were concentrated in North America and in India. However, those colonies were mostly lost to the British, and the French subsequently turned their attention to Africa and to east Asia.

French colonialist entrepreneurs managed to re-establish France as a colonial power by seizing land - first in Algeria and then across Africa and southeast Asia. France's push for colonization occurred despite the country's longstanding republican tradition established by the 1789 French Revolution (which, in true 19th-century tradition, didn't apply to anyone you labeled "uncivilized"). France thus had to turn to concepts such as the "Mission to Civilize"[4] in order to convince its more liberal voters that colonialism was a good thing for conquered and conqueror alike.

At its apex in 1920, the French colonial empire was the 6th-largest empire in history, narrowly losing out to the Qing dynasty and Spanish realms.[5]

French colonies and possessions[edit]

First colonial empire[edit]

New France[edit]

Like the British, the French started to get interested in New World colonization due to the riches enjoyed by the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. France's attempts to establish colonial outposts in the Americas were originally stymied by Iberian vigilance as well as France's own internal problems such as the Wars of Religion.[6]

In 1605, however, the French managed to establish Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia, Canada.[7] A few years later in 1608, explorer and conqueror Samuel de Champlain established Quebec as a trading fort.[8] Quebec very quickly became an important administrative center due to its position as a trade and travel hub.

While their English rivals sought to conquer land in North America, the French had a different goal. They sought to exploit the New World's wealth through trade, and they learned native languages and intermarried into the tribes.[9] As a result, New France was sparsely populated by whites, and most of the colonists who arrived were involved in trade. New France gradually expanded to encompass much of eastern Canada.

In 1629, France went to war with England, and the disparity of their strengths in North America became evident when the English managed to overrun New France.[10] The French colony never quite recovered from that blow. Administration stagnated, even after the French tried privatizing it through a bunch of colonial charter companies. In 1663, the white population numbered scarcely 3,000 people, only around 1% of the land was being exploited by white workers, and French missionaries had little success converting natives to Catholicism.[11]

Despite this lack of success, the French did benefit from having much better relations with Native Americans than the other European colonizers. This is primarily due to the fact that the French generally treated the natives with respect and weren't overly interested in conquering their tribal lands. French policy towards the natives was harmonious because French explorers had quickly discovered that Native Americans were quite eager and willing to sell valuable furs in exchange for European manufactured goods like pots and pans as well as European horses.[12] Since the French were focused on trade anyways, this meant that they had no need to wantonly attack Native Americans. French traders went on to learn native languages and customs in order to recruit guides and helpers and conduct diplomacy. The friendly relations between the French and the natives meant that, when wars ensued with England, France generally had far more native allies.[13]

As progressive as the French were, it ended up costing them in the end. The English colonies grew faster and had a greater population, and this led them to final victory in the French and Indian War. New France was annexed as a colony of Britain.

French Louisiana[edit]

"A wrong turn? So, I was supposed to turn left at the big pile of rocks?"

Louisiana was sort of founded as a French colony by René-Robert Cavelier, who led an expedition down the Mississippi River and claimed the entire region in the name of Louis XIV.[14] He had, however, neglected to substantiate that claim by building a settlement. It wasn't until about a decade later that the French sent more explorers up and down the length of the river to find a suitable place for a fort, and this led to the construction of Fort Maurepas on the coast of what is now the US state of Mississippi.[15]

The French were keen on making money from this colonial venture as well, so they encouraged wannabe farmers to move out there and start growing tobacco, and they also started trading in deerskin.[16] Of course, no European agricultural production effort in the Seventeenth Century could continue without the addition of black slaves, and the French sent them out to the colony in droves as well. As in Canada, the French traded heavily with Native Americans and got along with them more harmoniously than the British did.

Louisiana was also lost to France during the French and Indian War, this time being handed off to the Spanish Empire. France briefly reacquired it, but Napoleon Bonaparte sold it off to the United States after realizing that he had no way of defending or exploiting the colony.

Saint-Domingue[edit]

France also fought many conflicts with the Spanish in the Caribbean while seeking to establish a foothold there. In 1697, the two powers used the treaty which ended the War of the League of Augsburg to settle their dispute over the island of Hispaniola, with France receiving the western third.[17] France renamed its portion of the island as Saint-Domingue after Saint Dominic.

Saint-Domingue rapidly grew to become France's most valuable colonial possession, with plantations springing up to produce and sell sugar, coffee, tobacco, indigo, and cotton.[18] These plantations required a huge amount of slave labor, and Europeans were hugely outnumbered. In 1788, the French census counted 25,000 whites and 700,000 slaves.[19] Meanwhile, industrial agriculture devastated Haiti's ecosystem, with deforestation causing erosion and unwise planting decisions causing soil exhaustion.[18] French landowners treated their slaves atrociously, and an unknowable number of slaves perished from malnutrition, exposure, and disease.[18] Life expectancy for slaves was just 21 years.[20]

As any modern person with a brain knows, you can't have a huge slave population and treat them like dirt for too long before they start to get fed up. Haiti's slave population started rising up in 1791, with Toussaint Louverture emerging as a significant leader. The French reacted with horrific brutality. Thousands of Haitians were burned, drowned, and buried alive, and the war swept across the colony and destroyed its prosperous plantations.[20] The former slaves were left in an environment which had been destroyed by French excesses, and they were surrounded by states which had no desire to see a free slave republic succeed.

Haiti won its independence, but its problems had only just begun.

French Guiana[edit]

The French had an extremely difficult time making inroads into South America, as the Portuguese were quite effective at swatting them off. The Dutch also competed with the French in that region. After France was stripped of most of her North American colonies by the British in the Seven Years' War, the French turned their attention towards their little corner of South America.

French Guiana has a very sad history. First, it saw many thousands of Africans imported as slaves to be treated horribly, and the region's natives were also brutalized and enslaved.[21] The evil of slavery did not end when the institution was ended there in 1848; it was prolonged by the use of forced contract workers. After that, Napoleon III turned part of the region into a penal colony where tens of thousands of people were deported and viciously abused for minor crimes; that style of punishment lasted until 1946.[22] One of French Guiana's most famous prisoners was Alfred Dreyfus, who was basically arrested for the crime of existing while Jewish.

French India[edit]

The French were also late getting into the Indian spice trade, and they had to look on jealously as the British East India Company made inroads into northern India and the Dutch East India Company smashed into Indonesia. France decided to copy those other powers by forming the French East India Company in 1664 in the hopes that they could get in on some of that cash flow.[23] The French Company later took advantage of the Mughal Empire's decline to start shaking hands and doing deals with the recently-freed Indian princes in the southern part of the continent. They peacefully acquired the port zones of Pondichery, Mahe, and Karaikal.

As in North America, the French made alliances with local rulers in the hopes of turning them against the British. As in North America, this somewhat backfired. In 1756, the French managed to talk the Newab of Bengal into attacking the British; Bengal lost that battle and the British used that opportunity to start seizing land in India.[24] France subsequently lost its influence in India after the Seven Years' War, leaving the British Empire as the dominant power there.[25]

Second colonial empire[edit]

French Algeria[edit]

France in 1830 was in a precarious political position due to the republic having been replaced with a new monarchy. To solidify his reign, the unpopular Charles X decided to distract the French people by declaring a war of colonial conquest against the Amazigh state of Algiers.[26] France launched naval invasion of the Algiers coastline, swiftly taking the territory and defeating the armies of the Ottoman Empire, of which Algiers was a loose vassal.[27] The war was extremely brutal, and even after it "ended", native Algerians fought a prolonged insurgency against the French conquerors. Ben Kiernan, an Australian expert on the Cambodian genocide, also considers France's actions in Algeria as genocidal, writing in 2007 that,[28]

“”By 1875, the French conquest was complete. The war had killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians since 1830. A long shadow of genocidal hatred persisted, provoking a French author to protest in 1882 that in Algeria, "we hear it repeated every day that we must expel the native and if necessary destroy him."

|

French rule in Algeria was more of the same old story. White Europeans held over 30% of Algeria's arable land, and of course they picked out all of the best parts.[29] Europeans also possessed most of the wealth and political power. After all, colonies are never for the benefit of the colonized, no matter what the government might say. The French colonial regime also imposed higher taxes on Algerian Muslims than on white Europeans. Algerian schools, traditionally operated by Islamic authorities, were shut down due to orders from the French colonial authorities.[30] That had about the impact you'd expect on the literacy rate and education of Algerians.

If that wasn't bad enough, France also implemented what was essentially an apartheid regime. Called Indigénat, this French policy made native Algerians into second-class citizens with inferior legal rights and forced separation from white Europeans.[31] This racist policy was later applied across the French colonial empire. Napoleon III later decreed that native Algerians could appeal for French citizenship, but stipulated that they had to renounce Islam first.[32] As you can expect, that deal didn't have many takers. The other problem with that reform was that it specified that Algerians were not citizens of France, but rather subjects. That means that they were legally and officially denied any political rights. Muslim villages were razed and whole populations were deported into the desert to make way for European plantations and settlements.[33]

Algerians were treated brutally, especially when they tried to revolt. However, World War II helped bring Algerian nationalism to the forefront of the colony's politics. Both the Axis and the Anglo-American occupation forces broadcast messages in Arabic promising that the people of Algeria would be free if they sided with the appropriate team.[26] Algeria's quest for freedom resulted in the horrific Algerian War of Independence, which lasted between 1954 and 1962 and saw both sides commit acts of terrorism, crimes against humanity, and other acts of mass murder and atrocity.[34] The sheer viciousness of French conduct alienated Algerian civilians, French civilians, and France's international allies. The war ended with a cease-fire, and France finally conceded Algeria's independence.

French West Africa[edit]

French West Africa was a federation of eight French colonial territories, which the empire had acquired during the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s. These territories were Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), Dahomey (now Benin) and Niger. As in Algeria, the natives of these colonies were expressly forbidden the right to be called French citizens. They were subjects and were denied human rights.

Prior to outright colonization, the French had long been involved in western African affairs. This was primarily due to the French interests in the slave trade, especially to feed the ever-growing demand for slaves in Haiti.[35] As part of that process, the French established a few slave trading ports, mostly clustered around modern-day Senegal.

When the Scramble for Africa kicked off, the French competed heatedly with the British for colonies in Africa. While the British relied on colonial corporations and private armies to conquer much of their African land, the French did it with their state military.[35] The French military pitted itself against a large number of Muslim African powers which greatly impeded the colonizers' progress.

Unlike the British, who relied on local puppet rulers, the French brushed aside all of the natives and created their own administration from scratch. They also harshly punished native Africans for any infraction.[35] France justified itself by citing the "Mission to Civilize", but it really didn't do much to actually improve the lives of their African subjects.[36]

Once again, World War II forced the question of independence for France's western African colonies. Luckily, these countries were mostly spared the devastating war of independence that Algeria had to go through, as France didn't consider them so important. Thus, Charles de Gaulle admitted in 1944 that it was time to start preparing these countries for independence, and that goal was achieved by 1960.[37]

French Equatorial Africa[edit]

The French empire also decided to consolidate its holdings further south. This became French Equatorial Africa, a federation of four colonies: French Gabon, French Congo, Ubangi-Shari (today the Central African Republic) and French Chad. The conquest and administration of these territories occurred similarly to French West Africa. However, this part of the French Empire distinguished itself when Chad and the other colonies became the first French holdings to side with Free France against Vichy France.[38]

French Chad was considered one of the lowest priority colonies for France, and its modernization as a result proceeded very slowly.[38] This is just another example of how colonial priorities can set a country back by decades. French administrators also antagonized the natives by appropriating their land and forcing them to work effectively as slaves.

These colonies also benefited from the decline of the French after World War II, and they were allowed to gradually transition to independence.

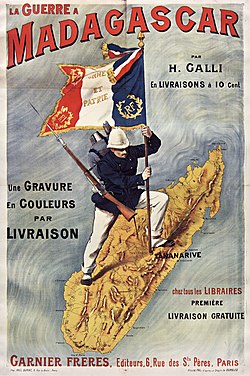

Madagascar[edit]

France also had ambitions to control Madagascar due to its strategic placement near southern Africa. France began to make serious inroads in the island's affairs by negotiating land and trade concessions. When Madagascar's monarch was deposed and replaced by a government which reneged on those concessions, France declared war in 1883.[39] France quickly won, and they extended a forced protectorate over Madagascar. When the monarchy of Madagascar tried to revolt against French rule, France attacked once more in 1896 and formally annexed the island.[40]

France then had to repeatedly crush revolts from Madagascar's natives. The island's people eventually won their path to independence by serving France in both world wars.[41]

French Indochina[edit]

France intervened incessantly in Vietnam and Indochina throughout the early Nineteenth Century. Much of that was done to protect the work of French and Spanish Catholic missionaries working in the region; the ruling Nguyễn dynasty opposed Catholicism due to the fear that the religion's insistence on monogamy would prevent Vietnamese monarchs from taking concubines.[42] When Vietnam executed two Spanish missionaries, France used it as an excuse to denounce Vietnam as an uncivilized nation which deserved to be invaded.[43] By 1862, France had seized the Cochinchina region in southern Vietnam and turned it into a colony.

France used that colony as a base from which to expand northward, but their imperialism threatened the interests of the Qing dynasty. France and China thus went to war in 1883 over the fate of Vietnam, a conflict which exposed the inadequacy of the Qing's modernization efforts.[44] France won and proceeded to annex all of Vietnam and spread its dominion across the entire Indochina region east of Thailand.

Designating the Indochina colony a "colonie d'exploitation" in 1887, France proceeded to strip the entire region of anything valuable.[45] First, French colonial authorities imposed high taxes on items the natives consumed until the natives couldn't pay any more. Then France turned to Indochina's natural resources, strip-mining for zinc, tin, and coal while establishing rubber, coffee, and tea plantations. As you can imagine, the people of Indochina didn't take this too kindly. Vietnamese revolutionary Phan Đình Phùng famously led an insurgency against French rule which lasted for decades until he died of dysentery in 1896; he had persisted even after the French desecrated the tombs of his ancestors and held his family hostage.[46]

During World War II, the Vichy government agreed to hand over Indochina to the Japanese. The Japanese were no kinder than the French, and Vietnamese resistance fighters organized the "Việt Nam Dộc Lập Đồng Minh", or "League for the Independence of Vietnam" to fight against Japan.[45] It was more commonly called the Việt Minh. When the Second World War ended, France tried to reoccupy Indochina, but ran right into the Viet Minh, who weren't exactly eager to see the old oppressors return to replace the previous oppressors. With weapons supplied by the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union, the Viet Minh violently resisted French colonialism. This conflict became known as the "First Indochina War". As in Algeria, the French reacted brutally. They're estimated to have killed between 60,000 and 250,000 civilians.[47]

Viet Minh forces finally managed to inflict a devastating military defeat against the French at the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, forcing France to acknowledge defeat.[48] France withdrew from the region, and Indochina was partitioned into Laos, Cambodia, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam.

Unfortunately, that was not the end of Indochina's suffering.

Morocco Protectorate[edit]

In 1904, France signed a secret treaty with Spain to partition the unfortunate nation of Morocco between them, with Spain getting the northern coast and the Western Sahara and France getting the middle chunk.[49] This rather quickly became known to the world. The German Empire still hated France for various reasons, and the feeling was mutual. Therefore, just to fuck with the French, Germany's Kaiser visited Morocco in 1905 to declare that Germany would personally guarantee Morocco's independence.[49] This sparked off the First Morocco Crisis, where both France and Germany completely refused to back down, and it really looked like World War I was about to start early. If killing millions of people over Morocco seems dumb to you, consider that the actual World War I started over Serbia. So, y'know.

Eventually, France and Germany calmed the fuck down. However, Germany sent a gunboat to Morocco in 1911, kicking off the Second Morocco Crisis.[49] Once again, it looked like Europe was going to tear itself apart for Morocco's sake, which just shows how stupid late Nineteenth Century imperialism really got. Germany finally agreed to France's protectorate over Morocco, but only in exchange for some land in Africa (most of modern-day Cameroon). That once again postponed war, but not for that long.

Although Morocco had been stripped of its independence, its sultan still theoretically reigned as the head of state. Sultan Abd al-Hafid abdicated after being forced to sign the instrument of protectorate, and he was replaced with a more pliable successor.[50] Tens of thousands of French colonists flooded into Morocco to begin making changes.[51] France also went on to recruit thousands of soldiers from Morocco to fight for France's interests in World War I, with the Moroccans becoming one of the most decorated units in the entire French Army.[52] Despite their service, Morocco would gain its independence only in 1956.

League of Nations mandates[edit]

Mandatory Syria[edit]

In accordance with the prior agreement with the British on how to dismantle the Ottoman Empire, the French ended up in charge of Syria. The Syrians, however, had other ideas. They didn't exactly appreciate being liberated from one empire only to have another step in to take its place. The Syrians first started attacking French colonial garrisons, and then they reorganized themselves as the Kingdom of Syria under a Hashemite monarch.

The League of Nations responded by organizing an emergency session to denounce the uprising and formally grant France the mandate to rule Syria, showing that the League really was just a colonialist tool.[53] Several months of war followed, and the French exiled the Hashemite King Faisal to Iraq and then assumed control in Syria.

French policy was the same old "divide and conquer" mentality used by the British. Their plan was to balkanize Syria into three pieces, an Alawi state in the north, a Sunni Muslim state at the center, and a Druze state in the south.[54] Ultimately, France decided on splitting Syria into five states: the Jabal Druze, Aleppo, Latakia, Damascus, and Alexandretta. This was because the French realized that they could prey on regional differences as well as religious ones.

After splitting Syria to ensure that it could never again unite against colonial rule, the French proceeded to clamp down on its people. France took control of Syria's economy, and the French language was mandated in schools.[54] As expected, the Syrians revolted, but the splitting of their state worked. Instead of facing a unified Syrian force, the French only had to deal with separate movements which were unsupported by each other.

That policy eventually backfired. The Druze state and the Damascus state attacked each other in 1925, and the resulting violence incited the French into shelling Damascus itself and killing 5,000 people.[54] The League of Nations, displeased with this, stated that, "The Commission thinks it beyond doubt that these oscillations in matters so calculated to encourage the controversies inspired by the rivalries of races, clans and religions, which are so keen in this country, to arouse all kinds of ambitions and to jeopardize serious moral and material interests, have maintained a condition of instability and unrest in the mandated territory."[54] Yeah, no shit. As a result of this pressure, France eventually agreed to cut out the bullshit and start letting the Syrians have a bit more of a say in the way their country was being run. By World War II, it seemed that Syria had a chance at independence in the near future, especially when they sided with Free France against Vichy.

Unfortunately, Charles de Gaulle went back on his word, and he refused to evacuate French troops from Syria.[55] The French retaliated against protests by once again bombing Damascus. Only after Winston Churchill (of all people!) threatened to intervene, did France finally agree to withdraw from Syria.[55]

State of Greater Lebanon[edit]

Along with cutting up Syria on religious and regional lines, France set aside Lebanon as a state for Maronite Christians. Maronites had actually sided with France during the latter's 1920 war with Syria, and the Maronites celebrated when the Arabs were defeated.[56]

Luckily, Lebanon had a much nicer experience as a French colony. France created a constitution for it in 1926, unicameral parliament called the Chamber of Deputies, a president, and a Council of Ministers, or cabinet.[57] The constitution was based on that of the French Third Republic. However, a key difference was that officials in Lebanon appointed political officers based on religion.[57] Another key difference was that the French colonial governor still had supreme authority in Lebanon, even to suspend the constitution.

Lebanon peacefully gained its independence during WWII. Syria and Lebanon both became founding members of the United Nations in 1946.[58]

Current status[edit]

France continues to rule fairly extensive territories outside of Europe and the territory commonly known as France. These areas generally are called Overseas France (Fr. France d'outre-mer). These territories moreover have a variety of legal and constitutional statuses:

French overseas departments and regions[edit]

These areas (Fr. départements et régions d’outre-mer) are considered integral parts of the French state, and their citizens are full citizens of France. They have representation according to their population in the French Parlement. These regions are:

- French Guiana (South America);

- Guadeloupe, and

- Martinique (Caribbean islands) and;

- Mayotte, and

- Réunion (Indian Ocean islands, off the coast of East Africa).

French overseas collectivities[edit]

These territories (Fr. collectivité d'outre-mer) have partial legal autonomy and some form of home rule, but they are still considered integral parts of French territory and their residents are French citizens. These include:

- The extensive Pacific island holdings of France that form French Polynesia

, whose capital is Tahiti;

, whose capital is Tahiti; - Wallis and Futuna, three small Pacific islands;

- St. Martin, and

- St. Barthélemy (Caribbean islands);

- St. Pierre and Miquelon, islands off the east coast of Canada.

The former French territory of New Caledonia![]() is in the process of transitioning to full independence.

is in the process of transitioning to full independence.

In addition to these, France also claims a sector of Antarctica and several small islands in the Southern Ocean with no permanent human inhabitants.[59]

Françafrique[edit]

“”For 48 years France has exploited the uranium in our country, and yet we still don’t have roads, medicines and in many places there is no water or electricity. France says we are independent now but we have no independence, we are modern slaves. They say this is an Africa problem, but we have had enough of what France is doing to us; it’s as if we’re still in the 15th century.

|

| —Mdou Moctar |

Even today, France still hasn't fully left many of its former colonies in Africa. After brutal colonial wars in places like Algeria, Madagascar and Vietnam, France instead opted for a system of neocolonialism that would allow them to more efficiently exploit many of their remaining colonies. Jacques Foccart![]() was responsible for drawing up a lot of treaties that, in exchange for protection against coups and some foreign aid, would allow France to obtain a continual military presence in these countries and French companies to have full access to many valuable resources.[61] France additionally was responsible for hand-picking many of the dictators that would take power in the region; this would result in many kleptocracies where the dictators would allow French companies to exploit their countries in exchange for their families making lots of money from French foreign aid, all while their countrymen starved.[62] Another way that France exerts control is through the CFA franc,

was responsible for drawing up a lot of treaties that, in exchange for protection against coups and some foreign aid, would allow France to obtain a continual military presence in these countries and French companies to have full access to many valuable resources.[61] France additionally was responsible for hand-picking many of the dictators that would take power in the region; this would result in many kleptocracies where the dictators would allow French companies to exploit their countries in exchange for their families making lots of money from French foreign aid, all while their countrymen starved.[62] Another way that France exerts control is through the CFA franc,![]() one of the few colonial currencies still in use today; this allows France to control the monetary policies of these countries and lets them economically punish countries that fall out of line, as they did with Mali when they tried to make their own currency in 1962.[63] France's military is another way that they maintain order, with France having intervened in Africa more than fifty times since 1960.[64] There has been a growing movement among African youth against France's neocolonialism, and despite some small reforms being made, France still has a large grip on much of Africa to this day.[65]

one of the few colonial currencies still in use today; this allows France to control the monetary policies of these countries and lets them economically punish countries that fall out of line, as they did with Mali when they tried to make their own currency in 1962.[63] France's military is another way that they maintain order, with France having intervened in Africa more than fifty times since 1960.[64] There has been a growing movement among African youth against France's neocolonialism, and despite some small reforms being made, France still has a large grip on much of Africa to this day.[65]

See also[edit]

- American Indian Wars

- German Empire

- British Empire

- Napoleon Bonaparte

- French Revolution

- Scramble for Africa

- Toussaint Louverture

- Vietnam War

References[edit]

- ↑ Colonial postcards and women as props for war-making. The New Yorker (2017).

- ↑ Aimé Césaire. Wikiquote.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on protectorate.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Mission civilatrice.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on List of largest empires.

- ↑ Steven R. Pendery, "A Survey Of French Fortifications In The New World, 1530–1650." in First Forts: Essays on the Archaeology of Proto-colonial Fortifications ed by Eric Klingelhofer (Brill 2010) pp. 41–64.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Port-Royal National Historic Site.

- ↑ Québec City. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ “The French and Indian War”. Native American Netroots.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Anglo-French War (1627–1629).

- ↑ New France. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ The French and Native American Relations. Ancestral Findings.

- ↑ Who Fought in the French and Indian War?. History of Massachusetts.

- ↑ René-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Fort Maurepas.

- ↑ A Failed Enterprise: The French Colonial Period in Mississippi. Mississippi History Now.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Peace of Ryswick.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Haiti. Britannica.

- ↑ Coupeau, Steeve (2008). The History of Haiti. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-313-34089-5.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Haiti: a long descent to hell. The Guardian.

- ↑ The rise of violence in French Guiana has roots in the colonial past. The Conversation.

- ↑ Inside the Brutal French Guiana Prison That Inspired ‘Papillon’. Atlas Obscura.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on French East India Company.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on French India.

- ↑ The Seven Years War and Britain's Passage to India. Real Clear Politics.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Algeria. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Invasion of Algiers in 1830.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 374. ISBN 9780300100983.

- ↑ Alistair Horne, page 62 "A Savage War of Peace", ISBN 0-670-61964-7

- ↑ Alistair Horne, pages 60-61 "A Savage War of Peace", ISBN 0-670-61964-7

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Indigénat.

- ↑ Debra Kelly. Autobiography and Independence: Selfhood and Creativity in North African Postcolonial Writing in French, Liverpool University Press, 2005, p. 43.

- ↑ Algiers: a city where France is the promised land – and still the enemy. The Guardian.

- ↑ Algerian War. Britannica.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 French in Africa. University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ The Mission Civilisatrice (1890-1945)

- ↑ 1960: The year of independence. France24.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 See the Wikipedia article on French Chad.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Franco-Hova Wars.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Second Madagascar expedition.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on French Madagascar.

- ↑ Owen, Norman G. (2005). The Emergence Of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History – Vietnam 1700 – 1885. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2890-5. p. 106

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Cochinchina Campaign.

- ↑ Sino-French War. Britannica.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 What Was French Indochina?. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Phan Đình Phùng.

- ↑ Valentino, Benjamin (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780801472732.

- ↑ First Indochina War: Battle of Dien Bien Phu. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Moroccan crises. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Abd al-Hafid of Morocco.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on French protectorate in Morocco.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Moroccan Division (France).

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Franco-Syrian War.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 Syria: The French Mandate. Country Studies.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Syria: WWII and Independence. Country Studies.

- ↑ Salibi, Kamal (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07196-4. p. 33

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Lebanon: The French Mandate. Country Studies.

- ↑ Founding Members. United Nations.

- ↑ See generally, The French Overseas Ministry (Fr.)

- ↑ 'We are modern slaves': Mdou Moctar, the Hendrix of the Sahara, Kim Willsher, The Guardian 21 March 2019

- ↑ Africa and France: An unfulfilled dream of independence?, Silja Fröhlich, DW News 3 August 2020

- ↑ Propping Up Africa's Dictators, John Feffer and Khadija Sharife, FPIF 22 June 2009

- ↑ Macron Isn’t So Post-Colonial After All, Mohamed Keita and Alex Gladstein, Foreign Policy 3 August 2021

- ↑ The flawed logic behind French military interventions in Africa, Nathaniel K. Powell, The Conversation 12 May 2020

- ↑ End of the CFA franc: A possible turning point in Francafrique?, Keanu Been, Global Risk Insights 18 March 2021