Ireland

“”We are a small nation. Our military strength in proportion to the mighty armaments of modern nations can never be considerable. Our strength as a nation will depend upon our economic freedom, and upon our moral and intellectual force. In these we can become a shining light in the world.

|

| —Michael Collins, Irish revolution leader and later Minister for Finance.[1] |

Ireland (Irish: Éire, pronounced “air-uh”), also known as the Republic of Ireland (Poblacht na hÉireann), is a country in north-western Europe located on the island of Ireland. It shares its only land border with Northern Ireland, a constituent country of the United Kingdom. Ireland is known for the incredible beauty of its landscape and ancient architecture, but it is unfortunately also known for violent historical political and religious disputes as well as its prolonged occupation at the hands of the English and later Great British Crown. Ireland has no official state religion, and its constitution guarantees religious freedom.[2] Nonetheless, 78.3% of the Irish population identify with Catholicism, while 1.3% identify as Muslim and 9.8% do not identify with any religion.[2] The overwhelming Catholic majority in Ireland has not prevented the country from adopting a fairly progressive social environment, as abortion was legalized in a 2018 referendum with overwhelming public support (though access can still be difficult)[3] and same sex marriage also became law in a 2015 referendum.[4] Ireland, in other words, tends to have its shit together. For the most part. These days.

Ireland's ancient Gaelic civilization on Ireland converted to Christianity in the 6th Century and came under repeated attacks by Viking raiders during the Middle Ages. While Viking incursions were pretty limited, the English were far more of a threat. After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the English began a gradual back-and-forth series of attempts to occupy Ireland. These wars were costly and expensive for the English, and they didn't succeed until 1603. England's attempts to culturally assimilate the Gaelic Irish and spread the new Protestant faith among them became the impetus for more centuries of war and resistance. Ireland was, in effect, England's first colony. Under English occupation, political power in Ireland was centralized under a Protestant elite class, with political rights only being granted if one were to take an oath acknowledging the English king as supreme in all matters temporal and religious. As you can imagine, the Irish people didn't like this arrangement very much.

In 1801, Ireland itself was abolished under the Acts of Union and folded into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Catholics finally won equal rights in 1829, but the Great Famine hit in 1845, making matters even worse. Amid inaction from the British government, over a million Irish people starved to death, and over a million more fled the island as refugees, with most of them ending up in the United States. Irish resistance finally peaked during World War I after a pre-war Home Rule Act was put aside to focus on the fighting. The unsuccessful 1916 Easter Rising saw the Irish rebel leaders put to death, which proved to be the last straw for the Irish people. A war of independence soon followed, and Ireland successfully broke away from the United Kingdom in 1922.

The bad shit wasn't over, though. Under the treaty allowing Ireland to break free, the 6 northernmost counties of Ireland would remain with the United Kingdom as Northern Ireland due to the more numerous Protestant population there. The Irish Free State, existing as a Dominion under the British Empire, would only consist of 26 counties, not the entire island. Outraged by this concession, "anti-treaty" forces revolted, beginning the Irish Civil War. This lasted for almost a year, and the bitter divisions remained in Irish society long after the "pro-treaty" faction prevailed. Ireland's three main political parties are all descended from these wartime factions.

In 1937, Ireland adopted a new constitution, it became a Republic free of the British Crown in 1948, and it focused on its internal affairs during the following decades. During the 1980s and 1990s, Ireland began cooperation with the United Kingdom in order to help resolve The Troubles, a bloody sectarian conflict which had erupted in Northern Ireland between Catholics and Protestants. In 1998, Ireland and Northern Ireland signed the Good Friday Agreement, creating shared institutions and reforming their governments in order to convince the sectarian factions to stop goddamn killing each other. So far, it's worked pretty well. Unfortunately, Brexit has cast some parts of it into question.

It is one of the richest countries in the world, having a GDP PC PPP greater than the UK. The parliament has two houses, the Dáil (lower house) and the Seanad (the fact it has been relocated to the Irish National History museum says it all); everybody else in Dublin lives in apartments (if they can afford the skyrocketing rent). The country is led by the Taoiseach (Prime Minister, roughly pronounced "TEE-shuck”) and the Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister, roughly pronounced "TAW-nish-tuh").

History[edit]

“”But there is one thing that the people of Ireland know how to do and that is to survive. You have to keep your faith and stay optimistic.

|

| —Pierce Brosnan, Irish actor and producer.[5] |

Gaelic Ireland[edit]

Due to the Midlandian Ice Age leaving the island of Ireland almost uninhabitable until about 15,000 BCE, the very first humans to live in Ireland didn't arrive until a whopping 40,000 years after people had begun living in Australia.[6] At some point between 600 and 150 BCE, Celts arrived from continental Europe in large numbers to subjugate the existing hunter-gatherers in Ireland and establish their own civilization.[7] (This will be a recurring theme). These Celts, known today as the Gaels, organized themselves into tuatha, or petty kingdoms.[7] About 150 of them existed, so don't even bother trying to list all of them, because we sure as hell aren't gonna do it here.

Ireland's isolated position away from Europe ensured that it remained largely untouched throughout the ancient period. While the Roman Empire conquered Great Britain and transformed it by establishing roads and towns, the Romans never bothered to go further and conquer Ireland (which they referred to as "Hibernia").[7] Like other Celtic regions like Gaul and Britannia, Gaelic Ireland was at this point a pagan realm following a set of traditions that modern historians usually call Druidism. Irish paganism was fairly distinct from the rest of the Druidic world due to its isolation, but Irish druids were also considered a learned class with supernatural abilities, most significantly the power to induce insanity in a victim.[8] Irish paganism also featured a belief in faeries, and druids were meant to be intermediaries between the world of men and the world of the fae. Ancient Gaelic Ireland was predominantly illiterate, so their culture and history was passed down through the generations by druids.

Medieval Ireland[edit]

The early Christian period[edit]

How the Gaelic Irish converted to Christianity is a fairly murky tale, as most historiography tends to focus on the role Saint Patrick played, to the detriment of understanding the broader cultural and religious changes happening around him.[9] Saint Patrick, born in Roman Britain, came to Ireland involuntarily, as he had been captured and sold there as a slave.[10] He believed his captivity there was punishment from God for being insufficiently pious, so he escaped and then came back sometime around 430 CE as a missionary to spread the Catholic faith.[10] Patrick successfully converted some Irish petty kings and traveled the island with his followers to build churches and schools.[10] Patrick's autobiography, Confession, is the earliest known Irish historical document..[11] Apart from Confession, however, there is unfortunately not much evidence directly linking Patrick with these accomplishments, and Patrick is more of a mythic figure than a historical one. Like we said, this period is pretty ambiguous and unknown. History is annoying sometimes.

While Patrick tended to focus on preaching to kings and druids, another Irish saint, Saint Brigid, became an abbess in Kildare around 450 CE and preached to the commoner class.[12] From this period, a large portion of the Irish population rather quickly adopted Christianity despite having been outside the Roman cultural sphere. Ireland's unique cultural position meant that the version of Catholicism practiced by the Irish people had some differences from mainstream Catholicism, giving rise to the concept of "Celtic Christianity." Contrary to the myths, Celtic Christians did not deny the authority of the Pope (they actually venerated him), nor were they more "spiritual" or "pro-woman".[13] Celtic Christians, did, however, have a different system for determining the date of Easter, and they gave a heavier emphasis to the concepts of penance and going into exile in the name of Christ.

Irish Catholicism also had a uniquely strong emphasis on monasticism. Monks and nuns would willingly live ascetic lives in secluded monasteries, where they would perform hard labor, pray, and study the Christian scriptures.[14] Monasteries, rather than bishops, became the cornerstone of the insular Irish governance of its Catholic Church, a situation that Rome wouldn't address until 664.[14] The people living within these monasteries were deliberately kept away from everyday public life so they could focus all of their attention on religion. They did, however, encourage visitors to attend religious lessons, where the monks would also teach literature and literacy.

Unfortunately for the monks and nuns, monasteries were very well known for their wealth, as they possessed chalices, jewelry, artworks, and surplus food.[15] They were also soft targets since they were inhabited largely by people who were untrained in combat. This made them appetizing targets for a certain infamous group of raiders who were about to arrive from Scandinavia.

Christ depicted in the Book of Kells

.

.

Oh no, the Vikings are here[edit]

| —Gwyn Jones, A History of the Vikings.[16] |

The Vikings started arriving sporadically to raid Irish targets in 795 CE, but they came in force in 840 CE.[17] The reason for their increased presence following 840 CE was the city of Dublin, which the Vikings established in 841 CE as a base of operations and gradually turned into a prosperous port town.[18] Under their governance, Dublin became the first truly urban region in Dublin and the island's first geographic link to the outside world. Other Viking bases, like Waterford, Limerick, Cork and Wexford, became Ireland's first set of towns.[17] After having dodged the Roman efforts to introduce urban areas into Great Britain, Ireland's entirely rural social structure had been changed forever.

While the Vikings had initially come to raid the monasteries, the establishment of towns and ports turned their focus from bloodshed and terror to trade instead. Killing people might have been fun, but the Norse had mouths to feed. From Dublin, trade routes linked Ireland to England, then the European continent, and then the Byzantine Empire.[17] Trade brought in gold, which the traders used to produce brooches and arm rings because even Vikings want to look fabulous. The first Irish coins were minted in Dublin in 997 CE, ordered by the Scandinavian king of Dublin, Sigtryggr Silkenbeard.[19]

Of course, the Gaelic Irish still plotted to fight back against the Norse interlopers. Irish pushback, despite being limited due to the myriad squabbling petty kingdoms being unable to unite, still managed to contain Viking expansion to their exclaves on the Irish coast. Despite what myth might say, the Norse at this point had converted to Christianity, and the Irish kings were more concerned with winning control of the Viking trade networks for themselves than driving out any dirty pagans.[16] In came High King Brian Boru, who ruled the regionally powerful realm of Munster. He had waged war for decades to win control over southern Ireland, and his campaign brought him against Norse Dublin. The resulting 1014 Battle of Clontarf is one of the most legendary in Irish history, and Brian Boru defeated the Norse forces at the cost of his own life, ending the Viking Age in Ireland.[16] From that point forward, Dublin and the other Norse towns were integrated back into Irish culture and politics. Ireland had fended off the foreign invaders.

Unfortunately, foreign invaders wouldn't be gone for long.

Oh shit, now the English are here[edit]

“”So completely is the history of the one country the reverse of the history of the other that the very names which to an Englishman mean glory, victory, and prosperity to an Irishman spell degradation, misery, and ruin... Freedom for the one meant slavery for the other; victory for the one meant defeat for the other; the good of the one was the evil of the other.

|

| —Cecil Woodham-Smith, English historian, The Great Hunger.[20] |

The Norman invasion[edit]

In 1066, Duke William the Bastard of Normandy (in northern France) famously invaded England to enforce his claim on the throne. His victory led to him being known as 'the Conqueror', and the Norman settlement of England caused dramatic changes to English culture, architecture, and politics.[21] This also set England on a collision course with France, which later resulted in centuries of bloodshed. Of course, the Normans weren't about to stop there. After all, these people were descended from the Norse (hence their similar name) and they had even conquered their way over to southern Italy to establish the Kingdom of Sicily under the de Hauteville dynasty.[22]

In 1169, by which time Norman rule had solidified in England, Diarmait Mac Murchada (Dermot MacMurrough), a deposed king of Leinster, sought permission from Pope Adrian IV and assistance from the Norman King Henry II in winning back his crown.[23] In exchange for an Norman army, MacMurrough swore fealty to Henry II and promised to grant Irish fiefdoms to Henry's knights. The Normans had spent a lot of time fighting in the continental free-for-all that was Europe, and their military tactics and technology were thus vastly superior. The Irish had no way to defeat knights who were fully clad in chainmail, and Leinster quickly fell to the invaders. In desperation, the Irish allied with what remained of their former Norse foes, and the Normans retaliated by sacking Dublin and slaughtering its inhabitants in 1170.[24] Good ol' Medieval warfare.

MacMurrough pledged his daughter Aoife to the infamous Norman mercenary Richard de Clare, better known as Strongbow.[23] Remembered as a cruel land-grabbing warlord, Strongbow eventually died of an ulcer in his foot that the Irish widely believed was a curse from their national saints.[25] The really weird thing is that this aggressive invader was found in 2005 to have been an ancestor of US President George W. Bush, meaning that some habits apparently ran in the family.[25] Strongbow's ambition, combined with his rise to the throne of Leinster in 1171, made King Henry II worried that the mercenary was about to go rogue on him. The king thus personally sailed to Ireland to put Strongbow in his place, becoming the first King of England to set foot on the Emerald Isle.[26] Strongbow submitted without a fight, and the 1175 Treaty of Windsor confirmed that Dublin and the petty kingdom of Leinster were now a part of the growing Anglo-Norman empire.[26]

To enforce the treaty, Henry II sent Norman military commanders to rule Ireland in his stead, largely without supervision. Irish farmers under Norman rule were reduced to serfdom, paying rent and tithes to their Norman lords for the privilege of farming the land their ancestors had lived in for centuries.[26] To prevent any troublesome uprisings, the Normans built castles across the Irish landscape.[27]

While less so than in England, the Norman invasion had a huge impact on the cultural fabric of Ireland. The ancient Irish legal system was replaced with English common law, and Norman lords introduced what are now common Irish surnames like Butler, Joyce, Fitzgerald, Fitzpatrick, and Redmond.[23]

England forgets about Ireland for a little while[edit]

Despite their overbearing early efforts, the Normans never managed to conquer all of Ireland, and by 1250 their presence there started to decline. This was for a few different reasons. Firstly, the English kings didn't consider Ireland to be terribly important for anything besides a vanity prize, and controlling all of Ireland wasn't key to said vanity.[28] Ireland, after all, didn't really produce a whole hell of a lot that couldn't be found in England, and its trade routes existed at the far edge of Europe. More important to the English kings were their ongoing fights against Scotland and France, as well as the occasional noble rebellion or sideshow conflict in Wales. In order to carry on fighting these wars, English kings repeatedly pulled resources out of Ireland, which wasn't terribly conducive to stable rule over the island.

The biggest English headache came after 1296, when King Edward I used some dynastic fuckery as an excuse to annex Scotland, causing a massive uprising against himself. The uprising, first with William Wallace's famous victory of the English at Stirling Bridge in 1297[29] and then Robert the Bruce's accession to the Scottish throne in 1306[30] and successful campaigns against the English were humiliating affairs for England. It also made certain anti-Norman Irish lords begin to question the possibility of seeking Scottish help for their own rebellion against English rule. After Robert's 1314 victory over the English at Bannockburn left him in control of Scotland at last, he answered Ireland's call for assistance by dispatching his younger brother Edward Bruce along with 6,000 soldiers to Ireland.[31] Edward Bruce's leadership of the Irish uprising was initially successful, enough so that the Irish proclaimed him their high king in 1316.[31] Unfortunately, a proper English army was finally sent against him in 1318, and Edward's forces were crushed. The English had Edward Bruce's corpse dismembered, with pieces of it displayed on the gates of major Irish towns and his head presented as a gift to English King Edward II.[32]

While Edward Bruce died pretty miserably, he had still dealt a major blow to the English yoke, and the Black Death further weakened England's resolve in holding Ireland. Furthermore, the Norman lords of Ireland by this point had begun adopting Irish culture and identifying with the Irish nation over England. Incensed at this situation, King Edward III sent his son to Ireland with news of a royal decree banning Norman lords from marrying Irish people, speaking the Irish language, dressing in Irish style, or listening to Irish music and stories.[28] The Normans of Ireland assured the prince that they would follow the law, and then proceeded to ignore it completely once the prince went home.[28]

By 1450, English rule over Ireland had decayed almost completely. The Norman-Irish lords had almost all gone native and abandoned their loyalty to the English Crown, but the English Crown couldn't do anything about it due to the ongoing Hundred Years' War against France occupying all of its resources. England's authority had shrunk to just four Irish counties (Louth, Meath, Dublin, and Kildare) which were marked out by stakes (called "pales") hammered into the ground.[33] Collectively called "The Pale", the English region rigidly enforced cultural restrictions by forbidding any within it from speaking Irish or marrying Irish, and all who entered from the rest of Ireland had to wear English style clothing.[33] To prevent cattle-rustling, the borders of the Pale were gradually fenced off, a situation which gives us the term "beyond the pale."[33]

The Tudor conquest[edit]

When the infamous king Henry VIII of England joined the Protestant Reformation by declaring himself the head of a independent Church of England in 1534, he immediately became a hated enemy of Catholic Europe.[34] The king dissolved Catholic monasteries in England in order to seize their wealth, and his successors went on to rigidly enforce Protestant religious doctrine and persecute Catholic clergy and followers.

With Spain now a firm enemy of England due to its loyalty to the papacy, Ireland took on a new strategic importance as a devoutly Catholic island right on the doorsteps of England that could be used as a potential staging ground for an invasion. The very same year Henry VIII broke with the pope, the petty kingdom of Kildare formally rebelled against England by declaring a "crusade" against the heretical king.[35] The Kildare revolt was quickly crushed, however, and Henry's regime began a more serious campaign of forcibly assimilating the Irish. Henry VIII instituted a loyal Irish parliament and had himself declared king of the island in 1541, declaring his intent to force his rule on Ireland.[35]

During this time England began to enforce martial law across Ireland in order to suppress growing discontent. Since Ireland wasn't fully under English rule at this time, this meant dispatching marshals across the countryside with the authority to execute tax offenders, suspected seditionists, and the wandering poor without trial, due process, or even regard to whether they were even nominally English subjects.[36] The soldiers enforcing this also weren't paid by the Crown; they instead had the authority to seize the property of the people they executed.[36] This obviously created incentive to kill and persecute as many people as possible, as the more people the marshals executed the more wealth they could steal.

Henry's successor, his son King Edward VI, added onto this policy by introducing the "plantations", where land taken from victims of execution would be resettled by Protestant English.[35] This was England's first major state-run effort to colonize a region, but a lack of manpower made this partially ineffective for the first decades of the policy. Under the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, English policy in Ireland changed to overt conquest. The campaign began in 1569 with the crushing of the petty kingdom of Ulster and rapidly escalated in ferocity.[37] The English treated the Irish the same way they would later treat the natives of North America: as a savage race to be exterminated. Along with widespread slaughter, English commanders like Humphrey Gilbert used methods of terror like lining their camps with decapitated Irish heads.[37]

Only Ulster, the first kingdom to fall, remained. Ulster had been placed under the leadership of the English-educated puppet ruler Hugh O'Neill, but O'Neill promptly cut his own strings and rebelled against the English as well. Under his leadership and training, the Irish quickly adapted to continental warfare techniques and turned the English conquest into an outright war. English commanders recognized the Irish under O'Neill as being just as formidable as the French or Spanish.[37] Spain also lent aid to its fellow Catholics in Ireland, sending soldiers to bolster the Irish ranks. Unfortunately O'Neill eventually fucked up by leading his troops outside of Ulster, where the unfamiliar territory placed them on equal footing with the English, where they could be crushed easily by greater numbers.[37] He surrendered in 1603, and Ulster became just another English realm governed by English laws and with Gaelic customs outlawed. Independent Irish rule had ended.

Under the English boot[edit]

Plantations and persecutions[edit]

“”In essence, James wanted to replace the Catholics of Ireland with Scottish Protestants... Basically, as he saw it, civilised people would spread out and improved the uncivilised who were around them.

|

| —Ted Cowan, Professor of Scottish History at the University of Glasgow.[38] |

1603 was a pretty huge year in British history. Not only had the last independent Irish ruler surrendered, but James VI of Scotland took the English throne after Queen Elizabeth I died heirless, at last unifying England and Scotland under the Stuart dynasty. For Ireland, though, this just meant an even greater power bloc against Irish interests. James was a firmly Protestant monarch, and he sought to subjugate the Catholic Irish by introducing his faith, and to do that he was going to introduce his people to them. The Plantation of Ulster targeted the Irish region that had most recently rebelled against the English, and it entailed settling the lands of the dispossessed rebel leaders with Protestant Scotsmen.[38] James hoped the increase in the Protestant population would make it harder for the Catholic Irish to resist conversion.

Settlement of Ulster was slow, but it was also steady since the farmland in Ireland was generally better than could be found in the impoverished Scotland.[38] Economically, the Plantation was a success, as the Scotsmen set up productive farms and exported their goods to Great Britain and the rest of Europe. Religiously, not so much. The Protestants introduced to Ireland brought with them religious strife, and the Irish kicked off their land to make way for the colonists responded violently. At least 10,000 Scots settlers were slaughtered by the resisting Irish during this period.[38]

Along with the plantations of Ulster and other Irish regions, the Stuart monarchs also stepped up restrictions on the Catholic Irish population. In 1607, Catholics were forbidden from holding government positions, and the Irish Parliament was rigged so that a majority of its seats would always be held by Protestants. The Crown also imposed penalties like fines and confiscation of property on anyone who refused to attend Protestant churches.[39]

Civil war comes to Ireland[edit]

After decades of English misrule, Catholic Irish in Ulster abruptly exploded into rebellion in 1641, seizing control of multiple counties and killing a great number of their Catholic neighbors. The previous year had been especially bad in Ireland, with a harvest failure crashing the economy and causing inflation to spike by 30%.[40] The new Protestant landowning class responded to these economic difficulties by hiking rents, seizing more land, and demanding higher tithes. As you can imagine, the Irish Catholics didn't appreciate this very much.

The Irish uprising also occurred against a backdrop of civil war beginning to erupt in England over the deteriorating relationship between King Charles I and his Parliament, and an earlier failed coup attempt against Dublin by Catholic radicals seeking to support their Catholic king.[40] After the Ulster uprising, the English yoke lifted temporarily as the English Civil War erupted the next year. The Irish had actually inadvertently helped cause the war, as the king's disagreement with Parliament over who would command the military forces sent to Ireland became the straw that broke the camel's back.[41]

Ireland declared itself a Catholic Confederation, with many Catholic English joining their cause as well.[42] Rather than break away completely, the Confederation hoped to offer support to King Charles I against the Parliamentary forces in exchange for him pardoning their rebellion and promising to respect the religious rights of Catholics.[41] Unlike the king, Parliament was run by Protestants who absolutely refused under any circumstances to negotiate with the Catholics and furthermore promised to pay off England's war debts by selling off confiscated Irish land.[41]

By 1644, the ceasefire went into effect between the Confederation and the king, and Irish forces sailed to Scotland to aid the royalists. The remaining Protestant English garrison based in Cork, however, mutinied and declared for Parliament, as did the Ulster Scots garrison and another Protestant army based in Londonderry.[41] They immediately engaged in bloody civil war against the Irish Confederation, which controlled most of the central part of the island.

Meanwhile, English publications and writers began a furious propaganda campaign focused around fabricating stories of Catholic Irish atrocities against the Protestants. Frequently occurring were tales of pregnant women having babies ripped from their wombs and dashed on rocks, which never seems to have occurred even once.[43] Tales of atrocities only served to encourage and justify bloody English retributions.

The Confederation's war effort was hamstrung by internal divisions. The Catholic English were generally fine with how things were run in Ireland and only wanted religious rights, while the Catholic clergy and native Irish wanted to upend the old power structures and establish true home rule.[41] Most of the Confederation's government was controlled by the Catholic English, who were promptly threatened with excommunication by the clergy. While these political divisions were being hashed out, the Confederation's attempt to take Dublin from English control failed miserably, and Parliamentary forces routed them twice in 1647 and 1648.[41]

Why the Irish hate Oliver Cromwell[edit]

“”I ordered the steeple of St. Peter's Church to be fired, when one of them was heard to say in the midst of the flames: 'God damn me, God confound me, I burn, I burn.' When the [garrison] submitted, their officers were knocked on the head; and every tenth man of the soldiers killed; and the rest shipped for the Barbadoes. I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgment of God upon these barbarous wretches...

|

| —Oliver Cromwell, "A Letter from Ireland Read in the House of Commons", 1649.[44] |

Oliver Cromwell is almost certainly the most hated man in Irish history, to the point where, in 1997, Irish leader Bertie Ahern stormed out of the British foreign secretary's office the moment he saw a painting of Cromwell hanging on the wall.[45] Ahern refused to return until someone removed the portrait of "that murdering bastard."

By 1649, King Charles I had been executed and Parliament was firmly in control of England. However, Ireland was still in uproar, so Parliamentary commander Oliver Cromwell embarked on an expedition to bring the island back under the English boot. Pacifying Ireland should have been fairly simple, since the Irish armies were weak and eager to negotiate peace, but Cromwell instead wanted to avenge the Protestants killed in the early days of the Irish uprising.[46]

Cromwell's first major engagement was at the city of Drogheda near Dublin, where he used artillery to smash down the city walls. Cromwell's troops stormed through the town and indiscriminately slaughtered over 2,000 of its inhabitants, and they sealed Catholic clergy inside St. Peter's Church before setting the building on fire.[47] In Ireland's south, the city of Wexford met a similar fate, with another estimated 2,000 being murdered by Cromwell's troops.[48] Destroying these cities served no military purpose, and doing so was actually counterproductive since the cities couldn't be used for shelter or supply anymore.

Irish soldiers who either survived the massacres or surrendered were deported to the Caribbean colonies, usually Barbados, as indentured servants to work in horrible conditions on contracts of up to seven years.[49] A 1659 pamphlet described the Irish indentured servants as, "grinding at the Mills attending the Fornaces, or digging in this scorching Island, having nothing to feed on... but Potatoe Roots."[49]

Intensifying oppression[edit]

After Cromwell's successful reconquest of Ireland, Parliament imposed the Act of Settlement in 1652 in order to punish the people of the island for their uprising. The Act of Settlement sought to completely remake Ireland's social structure. First, Catholic clergy were exempted from all pardons and either expelled overseas or executed.[50] Secondly, Irish landowners could and did have their lands confiscated to make way for Protestant colonists from Britain. As for the dispossessed? The English government deported roughly 40,000 people to the region of Connacht, which had far inferior farmland and rugged terrain.[50] Another 40,000 Irish were allowed to go into exile overseas, usually to Spain.[50] More Irish, many of them widows from the wars, were shipped off to England's growing colonial empire in North America. When England captured Jamaica from Spain in 1655, some 2,000 Irish boys and girls were sent there to form the first settlements of the new regime.[50] Of the thousands deported to the Caribbean as indentured servants during and after Cromwell's conquests, those who survived were able to gain small patches of land for themselves on the islands, but none were ever recorded to have returned to Ireland.[50]

This remained the grim status quo in Ireland until the Glorious Revolution of 1688, where the Catholic English monarch King James II was deposed and replaced with the Protestant William of Orange. James II's attempts to regain his throne won him support from the Irish Catholics, and a brief war broke out before the Williamite forces crushed the Irish in 1691.[51] Ireland's most recent show of disloyalty enraged Parliament, and they set about with a renewed effort to punish the Irish. This came in the form of a new legislative package of Penal Laws beginning that year that first required doctors, teachers, and clerks to take oaths against Catholicism in order to keep their jobs.[52] The next law allowed judges to compel any Irish person above the age of 18 to take the oath or else be jailed for 3 months.[52] The one after that forbade any Irish from sending their children overseas for education on pain of having their land and property confiscated.[52] Catholics attempting to run their own schools in Ireland would be either fined or imprisoned.[53] The next was a complete ban on intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics, combined with a clause that banned Catholics from inheriting property or wealth.[52]

The Protestant Ascendancy[edit]

“”Ireland was a conquered country, the Irish peasant a dispossessed man, his landlord an alien conqueror. There was no paternalism such as existed in England, no hereditary loyalty or feudal tie. The successive owners of the soil of Ireland regarded it merely as a source from which to extract as much money as possible...

|

| —Cecil Woodham-Smith, English historian, The Great Hunger.[20] |

Despite the severe legal disabilities imposed upon Irish Catholics, the 18th Century remained mostly peaceful. This period is known as the "Protestant Ascendancy", as the Anglophone Protestant ruling class of Ireland wielded absolute power with little formal opposition.[54] Protestants loyal to Great Britain controlled the vast majority of land in Ireland, while Catholics labored under them as little more than disenfranchised serfs. The ruling class, however, began to chafe at this situation, as they viewed themselves as Englishmen who were entitled to the same rights as anyone living in the actual Kingdom of Great Britain. Since they controlled the Irish Parliament, they pushed for that legislative body to have more rights independent of the Parliament in London. The growing autonomy of the Irish Parliament was seemingly confirmed when, in 1729, the world's first purpose-built bicameral parliament building was erected in Dublin for the institution's use.[55] Protestants in Ireland were also not happy that the English had imposed discriminatory trade regulations in Ireland, placing tariffs on Irish goods entering England but not allowing the Irish Parliament to impose the reverse arrangement.

Henry Grattan, an Irish patriot, managed to make his way into the Irish Parliament, but his eloquent speeches calling for reform in Ireland fell on deaf ears due to his constant position in the fringe opposition.[56] Grattan's main achievement was in convincing Parliament to grant the Irish Parliament legislative independence in 1782, meaning it could finally set its own tariff policy.[57] His calls for granting Catholics the right to vote and hold office were not heeded until 1793. At that point, the American Revolution and the French Revolution had sent shockwaves through Europe, and the Irish Catholics were thoroughly frustrated by the slow pace of reforms.

The United Kingdom[edit]

Uprising and the Acts of Union[edit]

In 1798, the Society of United Irishmen launched a violent uprising against British rule, having seen that the slow pace of reforms had been stalled by Britain's wars against France's new revolutionary regime.[58] In 1794, the organization had been banned due to collaborating with the French, but this only galvanized further efforts to recruit a militia for the inevitable outbreak of war. British soldiers, meanwhile, had largely been deployed elsewhere to deal with matters on the Continent and overseas.[58]

Unfortunately, at the outbreak of war, French aid failed to arrive due to British naval supremacy, and British garrison forces in Ireland retaliated by conducting public displays of torture, summary executions, mass arrests, and burnings of homes.[58] Irish forces involved in the uprising were treated as enemies of the state and executed, and some were burned alive.[59] Irish civilians were once again treated as targets for repression, and cities in County Wexford had their women subjected to mass war rape.[60]

After Britain got the situation under control, Parliament resolved to bring Ireland even further under control. This led to the Acts of Union being introduced in London in 1800, and members of the Irish Parliament were bribed and threatened into passing it themselves in 1801.[61] This had the effect of abolishing the Irish Parliament and folding the kingdom of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Ireland as an individual political entity was no more. This also dramatically reduced Ireland's representation in legislative affairs. The Irish Parliament once had 300 MPs, but they only got 100 seats in the Parliament in London.[62] Catholics, who had been able to vote for the Irish Parliament since 1793, were not able to vote in elections for the united Parliament.[57] Catholic emancipation was a distant prospect, and it didn't happen until 1829, when the right for Catholics to vote was packaged into a bill adding further enfranchisement barriers to the Irish peasantry.[63]

Ireland's political incorporation into the UK caused it to enter a prolonged economic recession due to the regulatory changes, and Ireland was unable to take advantage of the UK's position in the Industrial Revolution outside of Dublin and Belfast.[64]

The Great Famine (this part is really depressing)[edit]

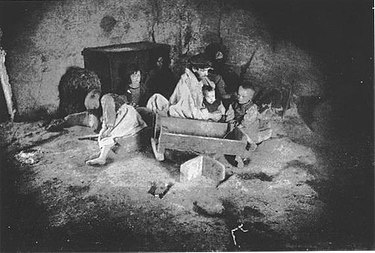

“”In the 1840s, after nearly seven hundred years of English domination, Irish poverty and Irish misery appalled the traveler. Housing conditions were wretched beyond words. The census of 1841 graded houses in Ireland into four classes; the fourth and lowest class consisted of windowless mud cabins of a single room; "nearly half of the families of the rural population," reported the census commissioners, "are living in the lowest state."

|

| —Cecil Woodham-Smith, English historian, The Great Hunger.[20] |

Under the rule of Queen Victoria, Ireland experienced the worst humanitarian catastrophe in its history. By the 19th Century, nearly 60% of Ireland's food needs were provided by potatoes, a hardy, calorie-heavy vegetable imported from the Western Hemisphere.[65] Phytophthora infestans, a fungus that targets potatoes, began infecting crops in the United States in 1843 before crop exports began spreading the disease across Europe, with the blight reaching Ireland in 1845.[66] A week after the blight was first detected in Dublin Botanical Gardens, the entire harvest of County Fermanagh had died off, and within two months all of western Ireland was experiencing harvest failure. Even worse, the blight returned with far more severity in 1846, causing a complete collapse of the potato harvest and eliminating almost two-thirds of Ireland's domestic food supply.

The complete destruction of the Irish potato crop could have been mitigated with the resulting increase in wheat imports from abroad had the British government stepped in to ensure food distribution and rationing, as by 1847 and beyond there was actually enough food present on the island to keep everyone fed.[65] Despite this, over one million Irish people starved to death.

Government failure came from the very top, as the Whigs had gained control of Parliament in 1846 and elected Lord John Russell as Prime Minister. Russell, a firm adherent to the laissez-faire approach to economics, accused his predecessor as having overreacted to the crisis and assured everyone that private merchants would be enough to ensure proper food supply in Ireland.[67] Public works programs were short-lived and paid hardly anything, soup-kitchens were very limited in scope and only operated for six months, and merchants kept exporting grain from Ireland as normal.[65] The idea of having the government pay for and distribute food directly to the starving was against the Whig government's ideals of small government and free enterprise and wasn't ever seriously considered.[65] Millions of Irish were thus left with no food, no money, no employment, still owing back-rent, and still weakened by malnutrition and disease. To emphasize the point of this policy, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Member of Parliament, Sir Charles Wood said,[68]

“”What has brought them, in great measure at least, to their present state of helplessness? Their habit of depending on government. What are we trying to do now? To force them upon their own resources. Of course they mismanage matters very much.

|

Religious prejudice also played a role in government inaction. Sir Charles Trevelyan, who was the official in charge of Irish relief policy, claimed in 1848 that the Famine was, "a punishment from God for an idle, ungrateful, and rebellious country; an indolent and un-self-reliant people."[69] This was also the same guy who said in 1847 that, "The only way to prevent the people from becoming habitually dependent on Government is to bring the food depots to a close."[68] In other words, Trevelyan was a pretty shitty person, and all the worse for being directly in charge of managing the government response to the famine.

As for Queen Victoria, she only took action in January 1847 by writing a letter asking the English public to donate to charity to support the Irish.[70] A full year later, the Queen made her own donation, sending a (relative to her wealth) paltry £2,000 to a British-run aid agency.[70] Since British policy was that no one could donate more than the monarch for fear of putting her to shame, no one ever donated more. Sultan Abdul-Majid I of the Ottoman Empire offered £10,000 from his own coffers, but the British government actually denied this charity.[70] Victoria didn't even bother to make a royal visit to Ireland until 1849, and she only toured the area around Dublin, which was the least impacted region.[70]

This catastrophe predictably caused a massive exodus of migrants from Ireland, and between 1845 and 1855 more than 1.5 million adults and children came to the United States.[71] Most had little more than the clothes they wore, and they suffered from a variety of ailments related to starvation. The American reaction to this was one of xenophobia, as the Irish came in great numbers, were poor, and were Catholics coming to a majority-Protestant nation. Businesses excluded Irish from the hiring process, and Irish-Americans were concentrated into impoverished ghettoes.[71] Gradually, however, the Irish-Americans became a major part of the American cultural landscape.

The Land War[edit]

During the Great Famine, the British Parliament blamed the Irish landowners for the ongoing crisis in Ireland and passed the Irish Poor Law Extension Act to dump the burden of paying for the disaster onto them. The problem here was that many of Ireland's estate owners were themselves deeply in debt with declining incomes and the threat of bankruptcy looming.

Charles Wood, Chancellor of the Exchequer, demanded that the costs of the famine be recouped as quickly as possible, ordering his subordinates to, "arrest, remand, do anything you can. Send horse, foot and dragoons."[72] The detestable Charles Trevelyan weighed in as well, saying,[72]

“”The principle of the Poor Law is that rate after rate should be levied, for the purpose of preserving life, until the landlord and the farmer either enable the people to support themselves by honest industry, or dispose of their estates to those who can perform this indispensable duty.

|

Government tax collectors turned Ireland upside down and shook it for the last pennies in the pockets of its people. They seized livestock, furniture, or anything else of value including the clothes and tools of former tax payers who had become homeless.[72] The landowners, meanwhile, had been made responsible under the Poor Law for the taxes owed by Irish peasants living on their estates. In order to remove that burden, they evicted tenants and broke up their little farms and villages, sometimes hiring local thugs to physically throw people out of their homes.[72] Hundreds of thousands of people were left wandering the Irish countryside with no money or shelter.

The aftermath of the Great Famine left the entire island in a prolonged economic recession. The Encumbered Estates Act of 1849 saw Irish land be sold off at bargain bin prices to British speculators who were interested only in squeezing profit from the land.[73] By that point, the most profitable use of Irish land was for cattle, so the new landlords intentionally hiked up rents beyond what Irish tenant farmers could pay, giving them an excuse to evict everyone to make way for livestock. Between 1849 and 1854 another 50,000 families were evicted.[73]

As you can imagine, the Irish spent the next few decades getting more and more pissed off. The year 1879 brought with it another failed harvest and fresh hardships inflicted by the blood-sucking British landlords. On 20 April, James Daly, owner of the Connaught Telegraph, Matt Harris, a member of the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and John O'Connor Power, an MP, met in County Mayo to organize tenant-defense associations and ally with other political agitation organizations across Ireland.[74] The national mood in Ireland turned from grim to revolutionary, and the National Land League was established to organize resistance to the landlords and receive payments from sympathetic Irish living in the United States. The League's nationalist leader, a young Charles Stewart Parnell, started organizing mass boycotts of landlords, burnings of leases, and sent men to physically block the authorities from evicting Irish families.[73] Police retaliated by battering rams and ladders to break into homes to evict people, and failing that they would simply burn the homes and the fields to make them unlivable.[75]

Attempts at reform[edit]

For his agitation, Parnell was arrested and sent to jail, and the Land League was suppressed. However, Parnell was able to organize a rent stoppage across much of Ireland to protest the British authorities' escalation of the matter.[76] In 1882, Parnell negotiated with the liberal British politician William Gladstone to get both sides to stand down in exchange for eliminating unpaid rents after a certain amount of time, but the peace was soon threatened when militant Irish murdered two senior British officials in Phoenix Park in Dublin.[76]

After his release from prison, Parnell turned to national politics and used donations from Irish-Americans to fund nationalist Irish willing to run for Parliament. By 1884, his Irish Party had 80 seats.[77] In 1886, Parnell's Irish Party teamed up with Gladstone's Liberal Party to campaign against the Conservatives under Lord Salisbury. In exchange for this cooperation, now Prime Minister Gladstone agreed to put a Home Rule bill up for debate, which would have reestablished the Irish Parliament and granted it certain rights within the British Empire.[78] Unfortunately, 93 of Gladstone's Liberals crossed the aisle to vote against the bill, and the divided Liberals lost the next election.

In 1892, Gladstone was able to make his return to the Prime Ministership, but his second Home Rule bill failed even harder than the first one.[78] Parnell, meanwhile, had become the target of an attempt to slander him. The Times published a letter, allegedly written by Parnell, that excused the Phoenix Park murders of 1882. However, the letter was soon proven to be a forgery, and the exonerated Parnell received a standing ovation.[76] Sadly, this didn't last long. Just a couple of years later, it was discovered that Parnell had been committing adultery by fucking his friend William O'Shea's wife behind his back, even being the real father of her three children.[76] No, this isn't a soap opera plot. This was real life. Goddamn. This revelation splintered the Irish Party and led to Parnell being disgraced, and he lost his Parliament seat and died soon after.

On the bright side, the push to reform the situation in Ireland outlived poor Parnell's political career. The 1903 and 1909 Land Purchase Acts passed through Parliament, providing the means by which Irish tenant farmers could purchase the land on which they lived. The 1903 law offered loans to Irish farmers to buy their land and compensated the landlords by offering them guaranteed government bonds.[79] The 1909 created an avenue by which this arrangement could be made mandatory if the government saw fit, a measure meant to relieve population congestion by rearranging small and impoverished farms in western Ireland.[79] This, combined with reforms to local governance, finally began to end the era of the shithead absentee landlord.

Ireland becomes a powder keg[edit]

The 1910 parliamentary elections suddenly threw Ireland into turmoil, as the pro-Home Rule faction had rather unexpectedly won enough seats to force through a bill if they chose.[80] The reason this immediately caused a political crisis was because not everyone in Ireland actually wanted Home Rule. These opponents to Home Rule were the Unionists, who wanted to maintain a firm union with the United Kingdom in order to keep their rights as Protestants, fearing that an independent Ireland would be a Catholics-only state. Dublin-born Edward Carson, for instance, had made a name for himself by campaigning against the Home Rule bill of 1893 (and also getting Oscar Wilde tossed in jail for homosexuality).[80] James Craig, another anti-Home Rule politician, is regarded as the founding father of Northern Ireland, being the heir to a huge whiskey business based out of Belfast.

By 1911, Unionists were holding rallies across Belfast and the Conservative Party was using opposition to Home Rule as a means to unite its constituents. On 9 April, 200,000 Unionists marched through Belfast to protest the introduction of the third Home Rule bill.[80] In 1912, as the debate in Parliament was heating up, 471,414 Protestants signed the Ulster Covenant, a document expressing their conviction that increasing Irish autonomy would threaten their religious rights and swearing to use all means to fight against Home Rule and defy any such laws from Parliament.[81] Women weren't allowed to sign the Ulster Covenant, but a separate document for them garnered about 234,000 signatures.

In 1913, the Unionist cause officially entered its militant phase with the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the drilling of about 12,000 militiamen at training centers scattered throughout the northern Irish counties.[82] By 1914, with the Home Rule bill's passage being imminent, more than 90,000 men had signed up for the UVF.[82] Irish nationalist groups, most notably the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), formed the Irish Volunteers, although its leaders were careful to state that they had no beef with the UVF (at that point).[83] Regardless, this dramatically increased the temperature of the simmering Irish cooking pot.

At the beginning of 1914, the British government considered using the military to suppress the UVF. This prompted a massive backlash from the army, as the British army had long been a hotbed of conservative sentiment and many of its officers were from Unionist Irish families.[84] The Irish Volunteers quickly realized the authorities weren't going to do anything to calm the situation in Ireland, so they began furiously stockpiling arms. This was gonna be bad.

Finally, in May 1914, Parliament passed the Home Rule Act, a move which promised to ignite the Irish powder keg.[85] Of course, if you know your history, you'll know that events conspired to interfere. You see, just a few months later, Austria-Hungary and its pal the German Empire would light a much bigger powder keg to start the Great War.

The powder keg explodes[edit]

The Easter Rising[edit]

“”If these men must die, would it not be better to die in their own country fighting for freedom for their class... than to go forth to strange countries and die slaughtering and slaughtered by their brothers... that profiteers might live?

|

| —James Connolly, leader of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA).[86] |

The outbreak of World War I shelved the Home Rule issue for understandable reasons, as political reform isn't typically a priority when the world is descending into a global armed conflict. John Redmond MP, leader of the Irish Party, urged Irish Catholics to volunteer to fight in His Majesty's Army, partially in return for the Liberal government having passed the Home Rule bill earlier in the year.[87] Other Irish wanted to earn some real battlefield experience to take home with them. Most, however, signed up due to reasons of poverty, having no better means to earn some cash and escape the still horrible conditions of Ireland.[87] Despite its political division and many reasons for antipathy towards London's interests, about 200,000 Irish honorably served among the UK's forces during the war in some real hellholes like Gallipoli and the Somme.[88]

Of course, World War I didn't prove to be the short affair everyone expected, and Home Rule was as a result shelved for a lot longer than the Irish wanted. Resentments started to rise again, as the implementation of Home Rule seemed likelier to be forgotten indefinitely. The Irish Nationalist cause became divided over whether to continue supporting Britain during the war or else make another attempt at an uprising while the British were distracted with Europe.[86]

The British government finally pushed the Irish to a breaking point by insisting that Home Rule would now only be implemented if the Irish agreed to be subject to conscription.[89] Irish nationalists of all persuasions, including the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Irish Volunteers, and the Irish Citizen Army, were outraged at the government's blatant games-playing. As violent revolt became inevitable, Irish-Americans once again began sending money to their homeland, and the German Empire also promised to ship weapons for the cause.[90] A German ship carrying guns was soon sunk off the Irish coast, but nationalists began arriving in person from the United States to fight for Ireland.[90]

The nationalists launched their insurrection on Easter 1916, seizing government buildings in Dublin and hoisting the revolutionary Irish tricolor flag.[86] Attempts to take other cities around the country failed, however, and the British were quick in organizing an armed response the next day. Dublin went under martial law, and British troops fought street-to-street to retake the city center. The extensive damage and civilian casualties caused by the fighting rapidly eroded public support for the uprising.[86] The British suffered 120 fatalities and over 400 wounded, while the Irish lost 60 men.[89] 180 civilians also died during the fighting.[89]

The heavy-handed British response in the aftermath of the uprising quickly reversed public opinion. British troops indiscriminately arrested thousands of people on suspicion of disloyalty, and 16 of the revolt's leaders were executed.[89] Other leaders, like the high-ranking Irish Volunteers commander Eamon de Valera, were sentenced to death but spared since they held American citizenship.[91] With France and Russia losing steam against the Central Powers, the UK wanted to keep a friendly relationship with the United States in the hopes of gaining a new ally. On the other hand, the Irish nationalists enjoyed renewed public backing for their cause, and leaders like Michael Collins studied the defeat of the Easter Rising in preparation for Ireland's next rebellion.

The War of Independence[edit]

After the Easter Rising, Ireland remained under martial law, a state of affairs that didn't really endear the British authorities to the Irish people. In response Sinn Féin, a fringe Irish nationalist party founded in 1905, saw a massive upswing in popularity that led it to win 73 of the 105 Irish seats at Westminster during the 1918 elections.[92] This was a majority of seats from every part of Ireland save the counties of Ulster. Rather than take these seats, the Irish nationalists formed their own Parliament in London and declared Irish independence. Eamon de Valera, who had made his name by being arrested and sentenced to death after the Easter Rising, became the president of this fledgling state, and Michael Collins became its finance minister.[93]

To defend this independence, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was formed in 1919 by merging the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army.[93] A few months after this, British authorities banned the Irish Parliament and the IRA as criminal organizations. The stage was set for a violent confrontation. Michael Collins assembled an assassination unit, and, in December of 1919, they attempted to kill the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the most senior British official in the country.[94] While the attack failed, this marked the turning point from peaceful resistance to overt violence.

The IRA started raiding British arms depots, Valera went to America to raise funds, and Irish rail workers went on strike to prevent the British from moving men or arms.[95] Prisoners arrested by the British went on hunger strikes to add to the political pressure. Irish farmers set up their own arbitration courts to settle land disputes in their favor, and they went on to completely supplant the British-run justice system in most of Ireland.[96] By 1920, the IRA had captured enough weapons to go on the offensive. Under Collins' leadership, the IRA conducted hit-and-run assaults to kill British police and military forces, with the hope of making Ireland so dangerous for them that the British would give up and either negotiate or fuck off.[93]

Later in 1920, the British retaliated by recruiting veterans who had gotten their screws loosened a bit in the hell of World War I and forming them into units known as the "Black and Tans" (after their mismatched uniforms).[93] The Black and Tans became infamous for using brutal violence and torture against the Irish civilian population. When one member was killed in the city of Cork, the Black and Tans burned the entire city down.[97] The Black and Tans frequently barked orders at groups of civilians and shot anyone who didn't immediately obey.[97] They would torture people they took prisoner by cutting out tongues, disfiguring faces, and cutting people's hearts out while they were still alive.[97]

One of the worst British reprisals came on "Bloody Sunday" in 1920, where British forces shot indiscriminately into a crowd at Croke Park, killing three schoolboys aged 10, 11 and 14, and a bride-to-be who was due to get married within days.[98] This act did not win the hearts and minds of the Irish people.

In the north, meanwhile, riots broke out across Ulster as unionists tried to fight back against the nationalists. In Belfast, British loyalists drove 7,000 Catholics out of the city, burned hundreds of homes, and murdered about 100 people.[95] The IRA stepped up its own violence by shooting suspected informers, burning the property of loyalists, and shooting captured soldiers and police.[95]

These tactics were costly in resources, though, and by 1921 the IRA was running short on ammunition. With both sides tiring of the war, they agreed to a truce on 11 July, 1921 to determine a political solution.[99]

Ireland partitioned[edit]

Meanwhile, in December 1920, the Parliament in London passed the Government of Ireland Act, which divided Ireland into two parts: Northern Ireland (6 counties of the Ulster region) and the rest of Ireland (the remaining 26 counties).[100] This was a stopgap measure meant to appease the Ulster unionists by assuaging their fears that Irish self-government would strand them inside a hostile Catholic nation. Partition was accepted by the unionists but furiously opposed by the nationalists. Part of the reason was a simple opposition to seeing the Emerald Isle split apart. But most of their opposition came from the fact that the British planners had placed two Catholic-majority nationalist counties inside of Northern Ireland in order to expand its size, meaning that a great number of Irish Catholics would now be stranded inside a hostile Protestant nation.[101] This would be the cause of some, uh, problems down the road.

Since Northern Ireland had gone quietly, it received Home Rule first, having its own parliament established alongside an executive government and judiciary. In Ireland, the rebels rejected Home Rule completely unless the partition was reversed, and Ireland never received its own Parliament under the Home Rule arrangement. Another legal body mandated by the Government of Ireland Act would have been the Council of Ireland, a joint committee to facilitate cooperation between the governments in Belfast and Dublin.[100] The Council died in the crib, as the Irish Catholics never deigned to consider it a possibility.

Since the British held the firm upper hand in Ulster, however, the Irish nationalists couldn't do anything about Northern Ireland becoming a thing. And so we now bid Northern Ireland farewell (for the most part) from this article (as they have their own), just as the Irish nationalists had to bid it farewell from their own independent Ireland.

The Irish Civil War[edit]

In December of 1921, Sinn Féin founder Arthur Griffith and assassination expert Michael Collins negotiated and signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, putting to an end the Irish War of Independence. Unfortunately, things were about to go bad again. On the issue of Home Rule, the British had largely caved and offered Ireland status as a Dominion, meaning it would have the same near-independence enjoyed by Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.[100] On the other hand, like those countries, Ireland would have to keep King George V and his successors as their head of state, and members of the Irish Parliament (Dáil Éireann) would have to swear loyalty to him in order to be seated.[100]

This, combined with Ireland's begrudging acceptance of the partition, was an outrage for the more hardline nationalists like Eamon de Valera, who considered the Treaty a betrayal of the Irish people and the ideals of Irish freedom.[100] Collins and de Valera, who had once been close friends, became bitter enemies over the matter (although their relationship had been on the rocks for a while previously).[102] Sinn Féin and the Irish nationalist movement as a whole split between the pro-Treaty faction and the anti-Treaty faction. Upon the Treaty's ratification, de Valera resigned as the President of Ireland and went on a speaking tour around Ireland in which he threatened that the IRA "would have to wade through the blood of the soldiers of the Irish Government, and perhaps through that of some members of the Irish Government to get their freedom".[103]

In his place, a pro-Treaty provisional government was established under the leadership of Collins and Griffith, and they set about organizing the National Army and a new police force. However, the National Army was built around the IRA, and most of the IRA hated the Treaty. As a result, most of Ireland's military barracks were controlled by forces who were becoming hostile to the government.[103]

Anti-Treaty forces soon barricaded themselves inside the Four Courts building in Dublin, the seat of the new Irish judiciary, in order to protest against the new government. After a tense standoff, Collins ordered the National Army to bombard them with artillery, an act of violence that kicked off the civil war.[104] Dublin descended into street-fighting for a week thereafter, and the Irish government gradually retook the city.

The "Republicans" or the "Irregulars", the new names for the anti-Treaty faction, outnumbered the government forces by roughly 15,000 men to 7,000, or over two-to-one.[103] On paper, this doesn't seem like good odds. The government did have some important advantages, though, in that it held most of Ireland's weaponry, and it was receiving aid from the British, who considered the Irish government to be a preferable alternative to the hardliner rebels. British supplies of artillery, aircraft, armored cars, machine guns, small arms and ammunition, combined with expert advisers who had learned much from the trenches of World War I, were decisive in ensuring the Irish government quickly took the upper hand.[103] While most of the countryside outside of Dublin was held by the Irregulars, the government was able to recruit and arm increasing numbers of soldiers and retake the major cities with relative ease.

By 1923, the Irregulars had been reduced to using guerrilla tactics against the government, and many of there fighters chose to go home rather than continue a hopeless war against their own people. Their only major victory was the assassination of Michael Collins,[105] which only served to deepen the national divide and make the government unwilling to accept de Valera's offer of a negotiated settlement.[103] By the end of that year, the Irregulars had largely either fizzled out or been defeated, and de Valera turned himself in to be arrested.[103]

Ireland goes its own way[edit]

A Catholic constitution, a Catholic state[edit]

“”In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity, from Whom is all authority and to Whom, as our final end, all actions both of men and States must be referred, We, the people of Éire, Humbly acknowledging all our obligations to our Divine Lord, Jesus Christ, Who sustained our fathers through centuries of trial...

|

| —the extremely religious preamble to the 1937 constitution.[106] |

After the civil war, the new Irish Free State's government was dominated by the pro-Treaty Sinn Féin party, the members of whom reorganized themselves as the Cumann na nGaedheal. It focused its efforts on establishing the new state, trying to block British efforts to influence Ireland, and turning the country in a more conservative direction.[107] In 1923, vice president Kevin O’Higgins defended his party's emphasis on the rights of landlords by saying, "we are the most conservative-minded revolutionaries that ever put through a successful revolution."[107]

The next year, Eamon de Valera was released from prison, and he promptly abandoned his policy of electoral absenteeism in order to found the Fianna Fáil, or the "Republican Party".[108] It formed the main opposition party, and its electoral fortunes improved as things in Ireland gradually got worse. The UK was the Ireland's main trading partner, and most of that trade was Irish agricultural exports. However, the UK's prolonged economic slump following the Great War combined with an interwar collapse in crop prices to ensure that the Irish economy never got off the ground.[109] A trade war with the UK over petty disputes and the onset of the Great Depression in 1932 caused the economy to collapse. After this, de Valera was finally able to take charge of Ireland at the head of a minority government.

De Valera immediately abolished the oath of allegiance, halted the land annuities that were being paid by Irish farmers to the British to pay off the 1903-9 Land Purchase Acts, and began dismantling the royalist constitution.[108] When King Edward III abdicated in 1936, de Valera pounced on the political opening and rammed a bill through the Dáil that removed all mention of the monarch and the Governor-General from the constitution.[108] He also formed a committee dedicated to writing a new constitution for the nation and finally introduced it in 1937.

The new Irish constitution was extremely Catholic in tone, and its preamble read more like a prayer than than a legal document meant to direct a nation. A clause in the new constitution granted the Catholic Church privileges just short of being a state religion, and the constitution included a controversial article about "women knowing their place at home".[110] The constitution also banned divorce and abortion, and it would have banned contraception had the Dáil not banned it already in 1935. All of this marked a drastic change from the old constitution, which had been far more secular in tone and intent. This was because the constitution had been written with heavy input from John Charles McQuaid, the Archbishop of Dublin, who had a close working relationship with de Valera.[110]

McQuaid's influence as Archbishop also stretched into public policy as well. Under his advice, the Dáil banned the new product "Tampax" because McQuaid was worried that girls might become aroused while applying them. No, really.[111] Gertrude Gaffney, a prominent columnist in the Irish press at the time, lambasted the direction the country was heading in, saying, "Mr. de Valera has always been a reactionary where women are concerned. He dislikes and distrusts us as a sex and his aim ever since he came into office has been to put us into what he considers is our place and keep us there."[110] In response, McQuaid warned de Valera against "godless feminism."

Neutrality in World War II[edit]

Luckily, Ireland was so busy being isolationist and Catholic that it didn't have any time for that fascism nonsense that swept through Europe during the Great Depression. Under de Valera's watch, Ireland's "fuck you" stance towards the UK slowly calmed down, but relations never approached friendliness. As a result, when the UK found itself at war with Nazi Germany in 1939, de Valera stated in no uncertain terms that Ireland would take no part in any hostilities. This was a pretty interesting move, since Ireland was at least nominally still a Dominion of the British Empire. Winston Churchill, a notable British politician and soon-to-be Prime Minister was pissed and had to be held back by the Cabinet from making any inflammatory remarks to the press.[112] US President Franklin D. Roosevelt wasn't any happier, and in his "Arsenal of Democracy" speech, he made mention of Ireland's choice, saying, "“Would Irish freedom be permitted as an amazing pet exception in an unfree world?"[112] In private, FDR was just as pissed as Churchill. Churchill even went so far as to offer to help end the Irish partition if Ireland directly aided the Allies, an offer which de Valera refused because a). reuniting Ireland would have almost certainly started a new civil war, b). nobody in Ireland wanted to get bombed, and c). de Valera didn't trust a word out of Churchill's mouth and thought Churchill might have just been drunk.[113]

Due to Ireland's neutrality, the UK was barred from utilizing any of Ireland's ports to launch anti-submarine sorties, even from those ports that the UK had recently owned as "Treaty Ports."[112] US ambassador David Gray repeatedly tried pressuring de Valera to open Ireland's ports, and upon the Taoiseach's refusal, would repeatedly disparage him to the US government.[112] On the other hand, de Valera made no effort to stop the roughly 40,000 Irishmen who volunteered to serve in Allied armies, nor did he try to stop around 200,000 civilians from crossing the border to work in British mines and factories.[114] German soldiers who arrived on Irish soil (usually downed airmen) were hunted down and arrested while British soldiers were returned to their homeland, and lighthouses around Ireland's coasts were painted and numbered to aid Allied navigators.[114] During the German bombing of Belfast, Irish fire crews crossed the border to help contain the damage.[114] Ireland also cooperated extensively with British intelligence to ensure that German agents couldn't get a foothold into the British isles.[112]

Despite these limited contributions to the Allied war effort, Ireland still wasn't looked upon favorably by the UK or the US. Roosevelt had expected the continuously positive relations between the US and Ireland to make de Valera amenable to allowing American warships into Irish ports, and he wasn't pleased when the answer was still no. In 1945, Churchill gave a speech in which he mentioned that the UK had even considered occupying Ireland by force, but had magnanimously refrained from doing so and thus "left the de Valera government to frolic with the Germans".[115] The comments provoked fury from Ireland. However, international opinion turned against the Irish even further when de Valera offered condolences to Germany after the death of Adolf Hitler,[116] which looked pretty bad since the Allies were in the middle of uncovering the horrors of the Holocaust.

Diplomatic isolation[edit]

Ireland didn't go unpunished for its relative lack of support for the Allies. Ireland's application to join the United Nations was rejected since the UN was at that point a club for the victors of World War II, a club to which Ireland obviously didn't belong. Ireland would be rejected repeatedly over the next 9 years due to the Soviet Union's vetos, as the Soviets believed Ireland would align and vote with the West.[117] Ireland only got in thanks to a 1955 package deal that tossed an equal number of communist and non-communist regimes together.

Meanwhile, de Valera's government got swept out of office in the 1948 election, and John Costello of the Fine Gael party took his place. Under Costello's watch, Ireland formally renounced its Dominion status, declared itself a republic, and left the British Commonwealth in 1949.[118] As for the ongoing Cold War, Ireland largely avoided joining the Western camp, contrary to Soviet fears. Ireland, while willing to negotiate a defense pact with the US, outright refused to join NATO until the status of Northern Ireland was resolved in a way that satisfied the Dublin government.[119] Ireland's time in the UN also didn't win it the affection of the Western bloc, as it took on a firm anti-imperialist stance similar to that of Sweden, which often put it at diplomatic opposition to the US and its European friends.[120]

Economically, Ireland wasn't doing so hot. The Irish economy remained in a state of depression in the 1950s. Poverty, unemployment, and mass emigration of its educated youth plagued the island. It was completely dependent on its exports to the UK for income. From that point up to 1973, Ireland was largely viewed by the rest of the world as an insignificant island at the margins of the global economy.

Modernization[edit]

The Celtic Tiger[edit]

In 1973, Ireland joined the European Communities (the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community, and the European Atomic Energy Community) in a move that was greatly popular with the Irish people.[121] In fact, Ireland had tried repeatedly to sign up throughout the 1960s, but France blocked them due to concerns about Ireland's protectionist policies and reliance on the UK's market.[121] In the end, this move paid off, but it wasn't so clear at first.

By the mid-1980s, Ireland had built up its infrastructure with European subsidies, but mismanagement from its incompetent government hampered economic growth . Political corruption was endemic, with Taoiseach Charles Haughey had misappropriated more than half a million pounds of state funds, all the while urging the country onto a path of fiscal austerity and tightening of belts.[122] This was an epidemic in the government, and civil servants were sucking millions out of the state.

The policy program meant to repair the flagging economy included reforming the tax code to attract foreign businesses, shifting its economy to a reliance on this policy instead of simple agriculture.[123] These corporate-friedly policies are still in place to this day, with Ireland being known as an international tax haven home to extensive operations by major tech corporations like Apple Inc.[124] Ireland also made university education free in 1996, leading to a well-educated workforce set up near quality universities.[123] A national healthcare system also made it easy and attractive for companies to bring willing employees into Ireland.[123] Ireland's membership in the European Communities and later the European Union also assured companies that their products coming from Ireland would have a pre-established export.[125]

As a result of these policies and a simultaneous US economic boom, Ireland's economy grew tremendously between 1995 and 2007. The country was called the "Celtic Tiger", in reference to the "Asian Tiger" economies of Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and South Korea, which all underwent rapid industrialization and economic growth during this period.[125]

Unfortunately, this rapid economic growth, built on right-wing policies, wasn't sustainable. The economic story doesn't end here, but first we have to talk about the other bad shit that started going down first...

Church scandals and the sins of the Fathers[edit]

“”When we were younger and abused, there was nobody to talk to, that we could trust. The priests, we couldn’t go near, they would laugh at us and call us liars. We couldn’t tell our parents, because they would have to go to the priest, and he’d do the same thing to them. We couldn’t tell the guards, because the guards and the priests, and teachers, were all big buddies.

|

| —Martin Gallagher, a child sexual abuse survivor.[127] |