British Empire

“”Rule Britannia! Britannia rule the waves, Britons never never never shall be slaves.

|

| —Chorus of "Rule Britannia."[1] |

“”When the British Empire finally sinks beneath the waves of history, it will leave behind it only two memorials: one is the game of Association Football and the other is the expression 'Fuck Off'.

|

| —Richard Turnbull, last British colonial governor of the Tanganyika Territory.[2] |

| The white man's burden Imperialism |

| The empires strike back |

| Veni, vidi, vici |

The British Empire was a global empire acquired and ruled by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It was initiated with voyages sponsored by the Tudors in North America, rebranded itself as the Commonwealth of Nations and exists today in a largely reduced form. At its height during the early Twentieth Century, the British Empire was the largest empire in the world, with no competition.[3] It very nearly covered the same surface area as the Moon.[4] The phrase "empire on which the sun never sets," which was originally applied to the Spanish Empire, is now more associated with the British due simply to its enormous size.[5]

The Empire began because the Tudors got jealous of what the Spanish and Portuguese were doing in the New World, and England began to establish colonies in North America and Asia.[6] The British grew in power in North America, eventually kicking out the Dutch and the French in a series of wars, most of which involved Native Americans. The British also made significant inroads into northern India, eventually defeating the Mughal Empire and taking their place as the subcontinent's regional power. In a span of 40 years, the British were responsible for the excess deaths of between 50 million and 165 million people in India.[7]

Britain suffered a setback when its oldest and most populous counties fought for independence in the American Revolution. However, British naval dominance led it to victory over Napoleon and other rivals, earning them the unquestionable position of first-rank world power. The Industrial Revolution greatly added to British power, and it moved on to bite huge chunks out of Africa during the Scramble for Africa in the late Nineteenth Century. After World War I, the British Empire incorporated much of what had been the German colonial empire and the Ottoman Empire. This was its territorial high water mark.

No empire, no matter how grand, lasts forever. The British Empire started facing economic competition from the United States and many of its colonies came under Axis occupation during World War II. Nazi Germany also managed to bomb the crap out of the British home islands. These hard sucker punches to the body meant that the British were in no position to keep hold of a quarter of the planet anymore. India broke free first, and many other British colonies followed. British humiliation was furthered by the Suez Crisis, when they were bitch-slapped by US President Dwight Eisenhower into abandoning a colonial invasion of Egypt.

Although it can still be said to exist, the British Empire is a shadow of its former self.

Governance[edit]

The British Empire ruled a vast array of different territories, and it had acquired many of them for different reasons and jumbled together an administration system to deal with each new colony after it had been secured. Therefore, it shouldn't be surprising that there were several different "kinds" of colony under British rule.

Crown colonies[edit]

Crown colonies are what you might think of as the "standard" kind of British colony. They were open to permanent settlement by British nationals, and their administrative affairs were largely controlled by the British government. The monarch would appoint colonial governors to manage the affairs of the colony, and the colony would often be able to elect its own regional legislature to advise that governor and wield limited powers.[8] Crown colonies later became much more centralized after the American Revolution broke the Crown's trust in regional representation, but the screws eventually loosened again in the late Nineteenth Century.

Crown colonies were renamed as "British Dependent Territories" in 1981, and they were renamed again in 2002 to be called "British Overseas Territories".[9]

Charter colonies[edit]

Most common in the early empire and largely used to form some of the Thirteen Colonies, the charter colony system refers to the process by which the English monarch would issue a "charter" to a group of people allowing them to go off to the New World and build themselves a new settlement.[10] The charter would also set down the ground rules under which the colony would be governed and how it would conduct relations with the Crown. A joint stock company was a project in which investors would buy shares of stock in building a new colony.[10] Depending on the success of the colony, each investor would receive some of the profits in proportion to the number of shares he bought.

Proprietary colonies[edit]

A special kind of charter colony was called the "proprietary colony". Under those terms, the monarch would essentially hand off land to the people he liked (or owed debt to) and set them up as the sole rulers of it.[10] Essentially, the colony would belong to a single person or family who was answerable only to the Crown. Rulers of proprietary colonies were known as Lord Proprietors.

A few notable instances of this are when the king gave territory to the Duke of York, who renamed it New York,[11] and when he granted land to William Penn, who named it Pennsylvania.[12]

Most proprietary colonies were eventually converted into Crown colonies.

Company colonies[edit]

Company colonies were granted to, guess what, companies. The Crown would issue a charter to a group of investors, and they would then form a company to trade, explore, or colonize.[13] In many cases, these companies would end up controlling a large amount of territory. This was a win-win deal. Companies got to make money from their ventures, but the Crown got to see its political influence expand rapidly under a series of self-sustaining actors.[14]

Probably the most famous and certainly the one which will be most discussed here is the British East India Company.

Protectorates[edit]

“”We present ourselves to you, Inhabitants of Cephalonia, not as invaders, with views of conquest, but as allies who hold forth to you the advantages of British protection.

|

| —British proclamation of protectorate over the Ionian Islands.[15] |

A protectorate is what happens when a stronger state extends its influence over a weaker state. Using that as a cover, the British were able to obtain many areas relatively peacefully by claiming that they intended to "protect" and "help" the local people rather than rule them. In reality, protectorates generally suffered more and more encroachments on their internal affairs, and many became British colonies in all but name.[15]

The princely states of India were notable as protectorates, as they were an integral part of how the British managed to rule the subcontinent.

Dominions[edit]

Dominions were what happened when some of the British Empire's largest and whitest colonies started to get antsy over the fact that they didn't have as many political rights as those people living on the British Isles. Trouble started when both the Canadian colonies and the Australian colonies decided to unite into Canada and Australia; by 1907 the Crown acknowledged their political notability by referring to them as "Dominions" for the first time.[16] The 1926 Balfour Declaration later specified what that term actually meant by stating Dominions to be, "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations."[17] In 1931, Parliament granted the Dominions full legislative independence.[18]

That act basically made the Dominions into independent nations. Indeed, by 1947, the term "Dominion" was dropped and replaced with "members of the Commonwealth".[19]

League of Nations mandates[edit]

After World War One, the British Empire and the French Empire had come into possession of a number of former German and Ottoman colonies and territories. However, they had officially sworn off any desire to obtain more colonies. How to deal with this? Enter the League of Nations, which granted the colonial powers "permission" to annex those new colonies as "mandates."[20] That's better. Now we can all have our shiny new colonies while still getting to pretend we're not hypocrites!

British colonies[edit]

Early empire[edit]

Britain itself formed part of the Roman Empire; subsequently invading Anglo-Saxon, Scots, Viking and Norman settlers took over. England continued its own colonial traditions by establishing the Angevin Empire![]() and conquering medieval Wales and Ireland before venturing futher afield under the Welsh Tudor and Scottish Stuart monarchs in the 16th and 17th centuries.

and conquering medieval Wales and Ireland before venturing futher afield under the Welsh Tudor and Scottish Stuart monarchs in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Thirteen Colonies[edit]

The Thirteen Colonies were among the first overseas territories acquired by the British. Jamestown, Virginia was founded in 1608 by English settlers as England's first permanent colony in mainland North America, but it unfortunately happened to have been built on the territory of the powerful Chief Wahunsunacawh of the Powhatan tribal confederation.[21] Agricultural fields which had been kept prepared for seasonal use by the Native Americans for generations were suddenly torn up by the English for the purpose of growing tobacco.[22] Needless to say, the Powhatan natives were pissed off, and thus began the decades-long Anglo-Powhatan Wars. Notable events included the Jamestown Massacre of 1622, when natives slaughtered several hundred English colonists, the kidnapping of Pocahontas by the English in 1613,[23] and the eventual English victory which came about due to a deliberate prolonging of the war to kill as many natives as possible.[24] Having won out, the English forced the Powhatan out of Virginia and sold hundreds of native prisoners into slavery.[22]

English colonialism was aided by the exile of Puritan religious minorities fleeing from Anglican persecution; this is why Plymouth Colony was founded.[25] English Catholics who fled from the government also ended up settling in Maryland, and this colony became the first in the New World to guarantee religious freedom for all mainstream Christian denominations.[26]

The Middle Colonies: Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, were extremely diverse. Nationalities included Swedes, Dutch, Germans, Scots-Irish and French, along with Native Americans and some enslaved (and freed) Africans.[27] Part of that is due to the fact that Sweden had built a colony on the Delaware River,[28] which was conquered by the Dutch and turned into New Netherlands[29], which was in turn conquered by the English. So there were a lot of different varieties of white people milling around. The Southern Colonies, meanwhile, were North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia. These places mostly focused their industries on producing cash crops like tobacco and (later) cotton, relying heavily on the use of enslaved Africans. Surely there's no bad thing that could result from that.

English colonists in the Thirteen Colonies repeatedly clashed with Native Americans, and they also got wrapped up in English colonial conflicts with the French and Dutch. In the end, however, liberal sentiments and anger over a variety of political issues led to the American Revolution and the independence of the colonies. They now call themselves the United States or something dumb like that, we dunno.

Proto-Canada[edit]

Newfoundland became British from the 1580s.

In 1670, the Crown established the Hudson's Bay Company to conduct the fur trade around the areas we now call northern Canada.[30] The land granted to the company by the Crown became known as Rupert's Land, which existed as a colony until 1869.[31] While the Hudson's Bay Company didn't own any of this land, it was effectively the only government there. It hired its own troops and mediated internal legal issues on an ad hoc basis. That was basically how things worked in Canada until the British Crown eventually decided that they ought to take more direct control of the land.

After the Seven Years War, the British used the 1766 Treaty of Paris to seize colonies from Britain's rivals, including French Quebec.[32] Quebec thus also became a British colony. To appease the large population of French Catholics, the British passed laws ensuring that there would be no discrimination against them and also granted a large chunk of the Ohio region to them.[33] That last bit was one of the grievances which led to the American Revolution.

Various Caribbean islands[edit]

The Caribbean was originally one of the more urgent and desirable places for colonial ventures because Spain and Portugal were making bank by selling sugar. Due to the harsh climate and hostility from the Iberians, British colonialism in the region didn't take off for quite some time. The first successful British colony was at Saint Kitts, established in 1623. The French also landed there, but at first the French and British teamed up to genocide the native Kalinago peoples of the island.[34] Then the French and British were free to fight each other over the land. After the British won out, Saint Kitts became a hotbed for the slave trade and the sugar-growing industry[35] which was really only to be expected due to the fact that Portugal and Spain had seen so much success doing the same.

Barbados was colonized in 1627, and it also became a major producer of sugar which relied on forced labor.[36] In that case, however, much of the labor came from English indentured servants along with enslaved Africans. In 1661, colonial authorities on Barbados established one of the world's first formal slave codes, which codified what slave owners could and could not do to their "property" as well as formalizing harsh restrictions on the lives of those slaves.[37] This heinous act was copied by other British colonies, most notably Jamaica and South Carolina.

Other British colonies in the Caribbean included Nevis (est. 1628) and the Bahamas (est. 1666).

Company Raj[edit]

The British began very quickly to start making inroads into India. Much of this happened under the banner of the British East India Company (EIC), which was formed in 1600 by royal charter to pursue British interests in the Indian spice trade.[38] The institution grew very quickly into the chief agent of British imperialism in Asia. Its territorial expansion initially began with diplomacy, leasing agreements, and purchases. The company built its first fortress in Madras, called Fort Saint George, in 1639.[39] Indeed, until about the 1750's or so, the company focused on trade rather than conquest. A few factors would change that.

First, the Mughal empire began rapidly declining, creating a power vacuum in India that the British could exploit. Secondly, the Carnatic Wars broke out between the British East India Company and the French East India Company, pitting not only the two corporations but also their Indian allies against each other to decide which European power would have trading privileges in the region.[40] Part of these conflicts was the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the keystone event which began the era of British imperial rule in India. When the Nawab of Bengal sided with the French, the British attacked in 1757 and won a decisive victory which later allowed them to capture the great city of Calcutta.[41] This left the British in control of much of the Bengal region. The British fully won out over the French, placing them as the sole dominant power in India.

Expansionism of the British East India Company rapidly accelerated at this point. The Anglo-Mysore Wars saw the Company slowly seize control over much of southern India[42] and the Anglo-Maratha Wars saw the last native threats in India defeated by the Company and allowed the Company to annex most of India's southeastern coastline.[43] Although the Company directly governed many parts of India, the place was just too big and too populous to completely annex. To deal with that problem, the Company allowed large portions of India to remain formally independent under monarchs who were allied to the Company and who acknowledged its supremacy.[44] These territories were called the "princely states".[note 1]

The British East India Company's rule in India, which lasted until 1858, is sometimes today referred to as the "Company Raj";[46] "raj" means "rule" in Hindi.

Later British Empire[edit]

Australian colonies and Commonwealth[edit]

Having lost their most populous colonies, the British sent out a fleet in search of a new place to dump their undesirables. In 1788, that fleet raised flag at Sydney Cove, beginning the age of British colonization in Australia.[48] Just as had happened in the Americas, the British unintentionally unleashed smallpox among the aboriginal population of Australia, resulting in the deaths of around 50% of their population.[49] Many thousands more aborigines were killed or murdered during the decades of frontier conflict with the colonists.[50] In 1869, the British government passed the "Aboriginal Protection Act" which did not protect aborigines. Instead, it established a central board to govern the Aboriginals affairs and force them to live in "reserves" where their lives could be completely dictated by the colonial government. They soon began removing all children of mixed descent from the reservations and into state-run boarding schools in the hope of forcibly assimilating them into white Anglo culture, a policy which was extended to all Aboriginal children in 1905 and continued until at least 1967.[51] Yuck.

If that reminds you of the actions of the United States, you're right. There was also a similar motive. Colonial expansion in Australia accelerated rapidly after explorers started finding gold in the 1850s.[52] Unfortunately, as was the case in the United States, whites tended to kick the natives aside when mining for gold.

Like the United States, Australia did not start off as a single polity. Rather, it comprised six colonies: Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia. Those last two were quite creatively named. Those self-governing colonies stayed that way for a long time, but in 1901, they agreed to unite into the Commonwealth of Australia.[53]

Malta and Ionian Islands[edit]

After losing the American colonies, the British Empire suffered yet more setbacks. It entered into a state of war with France due to the French Revolution, and it stayed at war with France for decades. When the brilliant general Napoleon Bonaparte came to power, the British realized they had come into conflict with a genuine rival for the first time since France had fallen in the Seven Years War. War against Napoleon also put the British against the Netherlands and Spain once more, but the British Empire finally managed to win out with the help of the Russian Empire and Prussia.

Among the spoils of war Britain received were the islands of Malta and the Ionian Islands. British rule started off badly for the people of Malta, as the British governor refused allow any Maltese to have a say in the island's governance.[54] Under British overlordship, Malta became overpopulated and impoverished, and it was denied home rule until 1921. The island later became the base for the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II.

Although theoretically independent, the Ionian Islands were in actuality ruled as little more than a colony. The islands' Greek population repeatedly protested and revolted against British "protection", and the British finally decided to give the islands to the newly-independent Greece in 1864.[55]

Cape Colony[edit]

“”What is the true and original root of Dutch aversion to British rule? It is the abiding fear and hatred of the movement that seeks to place the native on a level with the white man … the Kaffir is to be declared the brother of the European, to be constituted his legal equal, to be armed with political rights.

|

| —Winston Churchill on the Boer Wars, 1900.[56] |

Also among the spoils of war from the defeat of Napoleon was the formerly Dutch colony of Cape, in what is now South Africa. There were quite a few Dutch colonists still in the region, and they later became known as "Boers". Tensions between incoming British colonists and the Boers escalated quickly, especially after the British decided to abolish slavery in the Cape Colony.[57] Enraged at the apparent attack on their livelihoods, the Boer slave-owners decided that they'd rather flee through hundreds of miles of African wilderness than grant black people the basic dignity of being acknowledged as people. Thus began the Great Trek, an event which saw thousands of people pack up their belongings and move towards the interior of the African continent.[58] Although concerned about this, the British colonial authorities eventually decided that trying to stop the migration wasn't worth the trouble.[59] The Boers established their own independent states called the South African Republic (also known simply as the Transvaal), the Orange Free State, and the Natalia Republic. Surely they wouldn't run into any problems being neighbors to the British Empire. The British Empire loves its neighbors and always treated them with respect.

The British proceeded to attack the native peoples around the Cape Colony, most notably the Xhosa and eventually the Zulu.

British Malaya[edit]

The British East India Company, as has already been made apparent, did not limit itself to eastern India. Among its other colonial ventures were expeditions to both Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula. Between the Malay Peninsula and the island of Sumatra is a very narrow ocean passage called the Strait of Malacca; that passage has basically always been a strategically vital shipping lane between the Far East and the rest of the Old World.[60] It didn't take long for the British to start coveting control over this body of water. In 1786, the British acquired the island of Penang, and they also peacefully got the Singapore area in 1819.[61] Shortly after forcing the Dutch to cede the port city of Malacca, the British grouped these three cities under the title of "Straits Settlements."[62]

That still wasn't enough for the hungry British Empire. Mostly using diplomacy, the Company expanded its influence over the other states in Malaya. Most of those states would gradually agree to become protectorates of the empire, mostly controlling their domestic policies but forced to allow the British to represent them internationally. Four of those states were grouped together in a "federation" under more direct British control while the rest remained as separate states.[63] Life in British Malaya was characterized by both segregation between Europeans and other races as well as the high presence of brothels selling sex slaves.[64]

New Zealand[edit]

New Zealand was originally quite free of European presence even while the British Empire was expanding elsewhere. This, inevitably, had to come to an end. British merchants started stopping by the island around the 1830s to trade with the native Maori, and the British government very quickly decided that it was about time for New Zealand to be annexed.[65] Part of that was due to the economic activity there, and part of that was due to the fact that the French were also starting to covet the island.

To make that happen, the British sent a colonial governor to the island in the hopes that they could negotiate with the Maori and convince them to join the empire peacefully. The result of that was The Treaty of Waitangi. Unfortunately, it was a disputed document from the beginning. According to the British, the treaty saw the Maori sign away all of their rights, while according to the Maori, they were still entitled to their sovereignty.[66] Uh-oh.

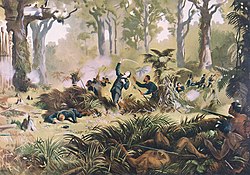

This situation resulted in open warfare in the 1840s. For decades, thousands of British and later New Zealand troops struggled to defeat Maori warriors using asymmetric warfare tactics, and the British eventually succeeded in confiscating most of the Maori tribal lands.[67] The Treaty and the wars are still heated political issues and sources of dispute in New Zealand to this day.

Hong Kong[edit]

For much of the previous century, the British public had been increasingly enamored with tea. However, at the time, there was really only one major producer of tea on the world stage: China. The problem was that the British Empire subscribed to the mercantilist belief that trade imbalances were bad for the health of an economy; the fact that Britain was importing so much tea while selling so little to China meant that British money was flowing into China.[68] The East India Company provided the solution to this problem: sell drugs to China. Chinese consumers were generally disinterested in European products, but they would still, like any other human being, get addicted to opium if given the opportunity. The British used plantations in India to produce opium and sold it to China in huge amounts. Eventually, the Qing got wise to the fact that the British were hustling drugs on their turf, and they banned the opium trade. In 1839, that ban became so intolerable to the British that they declared war.[69]

The war very quickly ended in a British victory, and the British wanted to make sure that their trade could not be so easily restricted again. To that end, they demanded ownership of a small set of islands in southern China for British merchants to use as a base of operations and a safe haven from Chinese persecution.[70] The British expanded the small settlement on Hong Kong and then made it into a formal Crown Colony in 1843. However, the following decades made it clear that the acquisition of Hong Kong had not changed very much about the Empire's trade relationship with the Qing dynasty. The British would go on to use the Second Opium War to force open Chinese trade as well as demand more land around Hong Kong.[70]

British Raj: The Jewel in the Crown[edit]

“”As long as we rule India, we are the greatest power in the world. If we lose it, we shall drop straight away to a third-rate Power.

|

| —Lord Curzon of Kedleston, Viceroy and Governor-general of India.[71] |

Although the British East India Company had ruled India for quite some time, all was not well. As you probably expect by this point, the Company didn't treat their Indian subjects very well. First, the Company had started to abuse a legal policy called the "doctrine of lapse" to annex large swathes of India illegitimately. According to the policy, the Company could annex princely states if their ruler died without a male heir or became incompetent, but the Company got to decide who counted as an heir and what made rulers incompetent.[72] Thus, the British had given themselves a blank check to annex any region in India at any time for any reason. Indians didn't like that.[citation NOT needed] Other causes for resentment existed as well. There were invasive attempts at social reform, extremely harsh taxes, and legal abuses aimed at Indian officials and princes.[73] Indians didn't like that either.[citation NOT needed]

The last straw came in 1857, when the British colonial authorities issued local Indian militias rifle cartridges that had allegedly been greased with pig's and cow's fat.[74] That was offensive to both Muslims and Hindus, meaning that the British had managed to piss off both of India's major religions. The so-called Sepoy Mutiny of the offended militias sparked an overall anti-colonial uprising that lasted for months. It was an extremely bloody affair, and the British ended up completely razing major cities like Delhi and Lucknow to put the rebellion down.[75] British troops also used an especially grotesque form of execution whereby they would lash an Indian to the mouth of a cannon and fire the weapon, blasting the man to pieces and scattering those pieces everywhere.[74] That was done in public as a means of inflicting terror upon the local population.

Although the rebellion eventually failed, it led to a complete restructuring of the British relationship with India. Parliament passed the Government of India Act 1858, liquidating the East India Company and formally annexing India as a British colony on equal footing with the others.[76] Queen Victoria then issued a proclamation to her new Indian subjects promising them rights equal to those of other British citizens.[77] That promise ended up being empty, but it did calm things down in India.

The British government created a new title for the region, calling it the "Empire of India".[78] Queen Victoria was thus crowned the first "Empress of India", and the government established the office of Viceroy to oversee affairs of the new colony.

The British also later invaded Burma in 1885 to add it to their Indian holdings.[79]

In total, the British Empire stole $45 trillion from India in today's value, although this amount is calculated by the amount of wealth that could have been generated in India.[80]

Dominion of Canada[edit]

Meanwhile, the British Empire's rule over Canada seemed to be facing resistance. French-Canadian nationalists had dominated Quebec's regional assembly for decades, and they repeatedly requested regional self-government from London.[81] The repeated denials of these requests combined with cultural tensions between French and Anglo-Canadians exploded into a violent revolt in 1837. The revolt was put down, but the rebels fled to the United States and mustered their strength to try it again in 1838.[81] The rebellion also encouraged Anglo colonists in northern Canada to rise up as well, as many people had long been denied civil rights due to having historical ties to the United States.

These uprisings shocked the British, and they sent politician Lord Durham to investigate how it could have happened. His findings prompted him to write the Durham Report, which recommended uniting Quebec and Rupert's Land into the Province of Canada and then introducing limited self-government.[82] These reforms eventually led to the Constitution Act of 1867, which divided the Province of Canada into Ontario and Quebec and then unified those provinces in a federation with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.[83] The Act also defined how Canada's new dominion government would work, and much of what it created still remains to this day.

Scramble for Africa[edit]

Unsurprisingly, the British Empire acquired a large number of new colonies during the great colonial land rush in Africa.

Suez Canal and Egyptian protectorate[edit]

In 1858, Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps created the Suez Canal Company to fund and construct a great waterway which would connect the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. Its financial backing came largely from French financial backers, although the government of Egypt also had a large stake.[84] Construction of the canal began just a year later in 1859, and the British Empire protested that the French were trying to weaken British dominance over trade between India and Europe.[85] The British had, after all, controlled those trade routes from naval bases in the Cape Colony. However, the canal's construction continued, with the French using forced labor for much of it until the Egyptians made them stop.[85] Construction finally completed in 1869.

Although the British originally opposed the project, they did get an opportunity to gain partial control of it. In 1875, Egypt went bankrupt and was forced to sell off its shares in the Suez Canal Company; the British immediately bought up the shares and became the major shareholder in the canal.[85] With Egypt cut off from any kind of influence over the canal, the Egyptian people became subject to increasing financial abuses by the colonial powers. In 1882, this helped spark an uprising against the Khedive of Egypt, and the British used the excuse to invade the country and force it into protectorate status.[86] From that point onwards, Egypt was effectively a colony of the Empire.

Union of South Africa[edit]

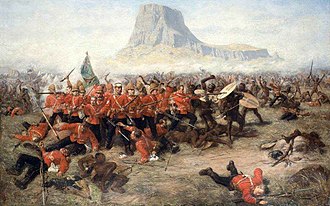

Having successfully created a federation to unite Canada, the British Empire started to wonder if they could do the same to unite the fractured region of South Africa, which was split between the British Cape Colony, the Zulus, and the Boer republics.[87] Lusting after Zulu territory, the British issued them an ultimatum in late 1878 which offered them a choice between submission to the Crown or war. The Zulus unsurprisingly chose war. British arrogance at the outset of hostilities helped the Zulus win a major victory at the Battle of Isandlwana despite having greatly inferior military technology.[88] Despite the initial setback, the British rallied and later won the war, annexing the Zulus as a result. The former Zulu kingdom became part of the Colony of Natal.[89]

The British then turned their attention to the Boer republics, which were the South African Republic (or Transvaal) and the Orange Free State. At first, it seemed that the British Empire and the Boer republics could live at peace with one another. Then the Boers had to go and mess things up for themselves by digging up a shitload of gold and diamonds in 1867, greatly increasing the value of their real estate and drawing the covetous eyes of the British Empire.[90] The Boer Wars followed, in which the British used concentration camps against Boer civilians.[91] After winning the wars, the British annexed the Orange Free State as the Orange River Colony,[92] and turned the South African Republic into the Transvaal Colony.[93]

Hoping to calm tensions in the region after the war, the British made it clear that they desired to unite the Boers with the existing British colonies of Cape and Natal and grant the resulting colonial federation dominion status like Canada and Australia. In 1909, this became reality with the South Africa Act, which created the Union of South Africa and created its government.[94]

Basutoland[edit]

South Africa also presented troubles that couldn't be solved by a union of colonies. Throughout the Nineteenth Century, the region of Lesotho was settled by Bantu-speaking peoples who fled the aggressive expansion of the Zulu.[95] The region eventually became a united kingdom led by King Moshoeshoe I. It almost immediately came into conflict with the Orange Free State, however, and in order to ensure its survival, Moshoeshoe appealed to the British Empire for protection.[95]

The Empire said agreed, naturally, and turned the kingdom into a protectorate in 1868. The British promptly betrayed Moshoeshoe by annexing his lands into the Cape Colony in 1871, but native resistance led the British to yoink the territory right back and turn it into the seperate colony of Basutoland.[96] The colony remained independent from the Union of South Africa, and it was only more determined in this goal after the Boers took power there and began implementing apartheid policies.

Bechuanaland[edit]

Like the Bantu people of Basutoland, the Khoisan people living in what is now Botswana were facing territorial encroachments by native enemies as well as the Boers.[97] In 1885, they appealed to the British for protection status, and the British responded by rolling in to annex them as British Bechuanaland. The protectorate eventually came under threat from the German Empire when the Germans established their colony in what is now Namibia.

Ultimately, however, the British always considered the Bechuanaland arrangement to be of secondary importance and possibly even a temporary arrangement, as there really wasn't anything terribly useful within the country's borders.[98] As a result, it was always administered by an outside polity of the empire, and it never received as much attention and development as other colonies. Even after gaining independence, Botswana was considered one of the world's poorest countries until around the 1970's, when they discovered diamonds in their soil.[97] At least they don't have to share the spoils with the goddamn British.

Rhodesia[edit]

“”I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. ... If there be a God, I think that what he would like me to do is paint as much of the map of Africa British Red as possible.

|

| —Cecil Rhodes.[99] |

The need to defend Botswana against the Germans led the British to privatize much of the effort, leading to the creation of the British South Africa Company, which was headed by ruthless businessman Cecil Rhodes.[98] It had authority over Botswana's infrastructure, such as it was, but decided to use that infrastructure to turn its attentions further north. Cecil Rhodes was a real piece of work. He was every inch the British imperialist, and he had the Hitler-esque view that the Anglo-Saxons were the world's master race and ought to make that a political reality by colonizing everything.[100] And we mean, everything. He once said, "I would annex the planets if I could; I often think of that."[99]

Rhodes used his newfound power as the head of the British South Africa Company to create a massive private army, reintroduce torture for black forced laborers, and attack and colonize the region of what is now Zimbabwe and Zambia and kill around 60,000 people.[100] He named the fruits of his colonial conquests "Northern Rhodesia" and "Southern Rhodesia", which is another insight into his character.

Naturally, the white colonists in those territories had all of the political power, and they used that political power to pass restrictive laws on the black Africans as well as confiscate and reserve about 50% of the colonies, what they considered to be the best land, for themselves.[101]

The Gold Coast[edit]

For centuries, the Gold Coast had been an important transshipment point in the Atlantic slave trade, especially since the nearby Ashanti people were quite happy to sell their defeated enemies as slaves.[102] The coastal parts of this area was taken over by the African Company of Merchants to further the company's role in the slave trade, but after the British Parliament abolished slavery and dissolved the company in 1808, the territory had to be governed directly by the Crown.[102] The British also started to become angry towards their former Ashanti friends, as they suspected that the Ashanti were still dealing in slaves even after the British had told them to cut it out.

The British underestimated the Ashanti, and they suffered losses in their initial expeditions, but enemies of the Ashanti still flocked to their side to avoid being annihilated by the aggressive Ashanti empire. The British finally defeated the Ashanti in battle in 1874, but by doing so they had completely destabilized the region. The Ashanti's enemies started declaring wars against them in their moment of weakness. To put an end to the chaos along their border, the British annexed the entire Ashanti empire into the Gold Coast colony.[102]

The Gold Coast colony is today the independent nation of Ghana.

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan[edit]

One of the factors that historically made Egypt significant was the Nile River. Realizing this, Egypt had, around 1820 or so, invaded the territory that is now Sudan in order to seize control of the waterway in its entirety. Egyptian rule over Sudan was extremely destructive; the government imposed high taxation, devastated Sudan's economy with harsh trade controls, and kidnapped large numbers of Sudanese to serve as slaves.[103] As always happens in such situations, the oppressed population was eventually fed up with the situation.

Further inflaming things was the increasing influence of an apocalyptic sect of Islam called Mahdism. Think Christian millennialism combined with the concept of jihad, and you'll not be too far off. In 1881, a Sudanese Islamic cleric, Muhammad Ahmad, proclaimed himself the Mahdi, or the "Guided One" who would restore Islamic greatness.[103] He took advantage of decades of Sudanese resentment against Egypt to declare a holy war and raise an army.

After the British Empire took control of Egypt, this holy war became their problem as well. The war started off poorly for the British, as their Egyptian subjects lost a battle at El Obeid in November 1883 before seeing much of western Sudan completely overrun.[104] At this point, the British considered Sudan a lost cause, but Major General Charles "Chinese" Gordon, the commander of British forces in the area, decided that the Sudanese forces posed too much of a threat to Egypt. Thus, he used a thin excuse to ignore his evacuation orders and instead decided to organize a defense of the Egyptian-controlled city of Khartoum.[104] Unable to take the city, the Mahdi's forces instead laid siege to the city for months, finally taking it in early 1885. Gordon was killed in the fighting despite the fact that the Mahdi had ordered him to be taken alive.

The disaster in Sudan led to a shift of power from the Liberals to the Tories, and the new Tory government decided that this would be a jolly good opportunity to extend British colonial rule "from Cape to Cairo".[105] International political concerns, however, led the British to plan the operation using Egyptian forces rather than their own. In 1898, the British were able to retake Khartoum and destroy the Mahdi's army. Thus in control of Sudan, the British Empire declared it to be a jointly administered territory between itself and its Egyptian subject state.[106]

After taking control of Sudan, the British made it their official policy to encourage tribal and religious divisions among its people in order to ensure that Sudan could never assemble a united anti-colonial revolt.[106] The result is still felt today, with the Muslim north having split from the Christian and pagan south in 2011 after much violence and civil war. The British also slowly edged Egypt out of the deal, taking almost sole control of Sudan by 1924.[106]

Nigeria Colony[edit]

A similar story applies here as elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. The British had maintained interests in the Nigerian coastal area for centuries due to their involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, exchanging manufactured goods and weapons for African prisoners.[107] After banning the slave trade, the British swapped to trading for palm oil. The British Navy, meanwhile, escalated its patrols in the region due to its attempts to crack down on the slave trade, and this quickly became an excuse to start gobbling up the region as a colony.

The British were especially urgent in annexing Nigeria due to the nearby presence of French and German expeditions during the Scramble for Africa. Previously, the Royal Niger Company had been placed in charge of acquiring the northern part of Nigeria in order to gain control of the entirety of the Niger river, but incursions by France and Germany convinced the British to buy out the company and administer the territory directly.[108]

The British generally chose to rule the colony indirectly through native puppet leaders, but in the south they directly established numerous Anglican schools in order to convert the pagan natives into Christians.[109] This actually sort of backfired because the graduates of these schools were literate and well-versed in British ways of thinking, which meant that they were perfectly prepared to start challenging British colonial rule.

Sadly, many of Nigeria's current problems are caused by the arbitrary ways in which the British decided the colony's borders and administrative policies. Nigeria, for instance, indiscriminately grouped together a feudal Muslim society in the north with a tribal pagan/Christian society in the south. Rumors spread throughout the entire colony that the British colonial administrators favored the more "civilized" Muslims over the pagans, and these rumors exacerbated tensions between the two regions.[110] These tensions exploded into the brutal Biafra War in 1967, and they are still felt to this day with the insurgency of Boko Haram.

British East Africa[edit]

Once again, the British Empire used slavery as an excuse for colonialism. In this case, they were targeting the Zanzibar sultanate, which had long been a hub for the Arab slave trade in eastern Africa.[111] The Empire pressured Zanzibar to abolish slavery at long last in 1874, which was undoubtedly a good thing. The British rested on their laurels for a bit until regional authorities discovered that the German Empire had sent some disguised dignitaries to the islands in order to negotiate for German control over the region.[112] In response to this competition, the British moved to claim the goods for themselves. They managed to threaten the Sultan of Zanzibar into handing over his lands, and they negotiated a treaty with the Germans separating their colony in modern-day Kenya from the German colony of Tanganyika.

British administration in Kenya was complicated by local resistance as well as the fact that the region had been devastated by slave raids and kidnappings.[112] It quickly became clear that there would be no profit from a Kenyan colony. The British looked further, to Uganda, which had access to the strategically important Lake Victoria. To control the country, the British negotiated a deal with the Germans where they handed over an island off the coast of western Germany in exchange for undisputed rule in Uganda and Zanzibar.[113] Uganda went on to become one of the wealthier African colonies under Britain due to its production of tea and coffee, and much of that wealth even stayed in African hands.

Sierra Leone[edit]

The coastal areas of Sierra Leone had been in British hands since about 1808 due to the fact that the Empire used it as a dumping ground for freed slaves.[114] In this manner, it was quite similar to the American colony in Libera, where the US dumped freed slaves. Although the British directly ruled the coast, they made "friendship treaties" with the tribal leaders further inland in order to keep the land secure. The status quo remained like this until the Scramble for Africa, when other colonial powers threatened to completely encircle the tiny British colony.

Realizing that they needed to expand their rule further inland to keep their colony secure, the British Empire declared a protectorate over inland Sierra Leone in 1896.[115] They had done this without consulting any of the natives, and this led to an anti-colonial revolt in 1898 which was rapidly put down.[116] British rule brought about widespread deforestation in the region as colonists sought to make way for cash crop plantations.

Divisions between the British blacks and the native blacks remained tense for the entire duration of the colony, and these tensions helped spark the Sierra Leone civil war shortly after the country's independence.[117]

League of Nations mandates: spoils of war[edit]

These colonies were theoretically granted to the British Empire under the authority of the League of Nations for the purpose of preparing them for independence. In reality, this arrangement was just a geopolitical cover for more British colonialism.

Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan[edit]

Prior to British occupation, Palestine and Jordan had spent centuries ruled by the Ottoman Empire. All things come to an end, though, and the Ottomans were forced to relinquish the region after being defeated in World War I and then completely dissolving. The mandate gave the British a "dual obligation" to Palestinians and Jews, and in practice the two groups of people were essentially governed under completely different legal codes and served by different sets of institutions.[118]

During British rule, conflict between Jews and Palestinians began to escalate quickly despite British efforts to end the violence. The mandatory government eventually caved under pressure and started restricting immigration and land rights for Jews.[119] In retaliation, Jewish Zionist paramilitary groups carried out a brutal and prolonged insurgency against British rule which eventually exhausted the British and convinced them to completely withdraw from the colony in 1947.[120]

The British Empire also had the go-to for imposition of a protectorate over the Transjordan region. It was ruled autonomously by the Hashemite dynasty, and it gradually transitioned into an independent state.[121]

Mandatory Iraq[edit]

One of the more disastrous decisions of the British Empire, Mandatory Iraq was created by merging the Ottoman provinces of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra.[122] Of course, informed people in the modern age already know about the problems Iraq faces, most especially the horrific and ongoing sectarian conflict between Sunnis and Shias as well as the Iraqi suppression of Kurds. That all happened in large part due to the British decision to throw these diverse people in a pot with each other without bothering to ask if they wanted it.

In order to maintain control over Iraq, the British put another Hashemite ruler in charge of the country. However, he was not actually from Iraq. Instead of viewing this as a problem, the British decided that this was a good thing because the Hashemite king would not feel confident enough in his own legitimacy to depart from his British puppet-masters.[123] The British fought tirelessly for control over Iraq, as they wanted control of the country's oil and the region served to connect the British Raj with the rest of the western Empire. The Iraqis resented this arrangement, and they fought against British rule during World War II and eventually managed to overthrow the British Hashemite puppet in 1958.[123]

Tanganyika Territory[edit]

British administration of this former German colony was pitiful, with little economic investment or aid.[124] In part this was due to the British Empire's money problems after the war, but it was aided by the fact that the League of Nations, despite its lofty stated ideals, just didn't really give a shit how these colonies were administered.

On the plus side, the British trained native peoples to act as their administrators, which gave them some of a say in the running of their affairs and helped pave the way for independence.

Chagos Islands[edit]

British Indian Ocean Territory primarily constituted the Diego Garcia military base on the Chagos Islands. This was legally contested: the island nation of Mauritius claimed they were forced to surrender the islands in 1965 in order to become independent (which happened in 1968), and the British kicked all the indigenous inhabitants off the Chagos archipelago from 1968 to 1974 so they could let the US build an airbase there and bomb all around the Indian Ocean. International bodies have consistently advocated for the rights of the displaced islanders, who have not been allowed to return under British governance. The United Nations in 2021 ruled the islands should belong to Mauritius, but the UK prefered to keep them as a vast stationary aircraft carrier.[125][126] A diplomatic breakthrough occurred in 2024, when the UK handed over sovereignty of the archipelago to Mauritius in exchange for continuing to lease the Diego Garcia military base.[127] With this transfer, the sun set over the entirety of the British Empire for the first time in over 200 years.[128]

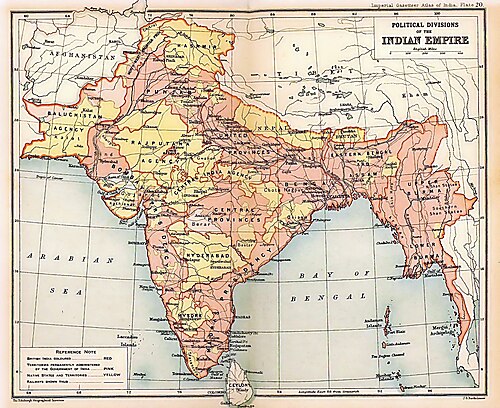

Map[edit]

Relics of Empire[edit]

- The place name Victoria

(after she-who-was-not amused) is found on every continent.[129][130]

(after she-who-was-not amused) is found on every continent.[129][130] - Cricket (except in America, where they play made-up-sports and have a "World Series" that only American teams play in. Oh, and those two times a Canadian team won instead.)

- Rugby - like American football but without the

players who are faster than olympic sprinters, as strong as competetive powerlifters and able to hit so hard that without armor, they would literally be killing each otherwussy crash helmets and late-1980s padded shoulders played by big girls blouses. - Hockey

- originally an

- originally an IndianMongolianIrishGreek game. - Tea

- Scones, with jam and cream (or cream and jam - it's complicated), and cucumber sandwiches

- Words entering the English language from diverse sources (but mostly India): Boomerang, bungalow, pukka, mogul, doolally, jodhpurs, gymkhana, curry, gnu (but not GNU), wildebeest, budgerigar, tobacco, anorak/parka, demerara sugar, polo, and loads more.

- A few far-flung island colonies, one peninsula, and a more-or-less universally unrecognised claim to 1/8 of Antarctica,[note 2] collectively known as the "British Overseas Territories".

- Homophobia, transphobia and other anti-LGBT sentiments in former British colonies.[131][132]

Modern fans of empire[edit]

The decline of the British Empire was long and slow: increasing independence for the white settled parts began in the late 19th century (Canada in stages from 1867, preceded by rebellions in 1837-1838), while British India became independent in 1948. In 1960 Harold Macmillan delivered the Wind of Change![]() speech which signalled acceptance of nationalism in the African part of the empire, and in the 1960s most African, Caribbean, and middle eastern British colonies gained independence, leaving only a few remnants with small populations. Since then, most of the colonies in the South Pacific and some of the smaller islands in the Caribbean have become independent, with only a few tiny places, typically those valuable as naval or air bases, remaining.

speech which signalled acceptance of nationalism in the African part of the empire, and in the 1960s most African, Caribbean, and middle eastern British colonies gained independence, leaving only a few remnants with small populations. Since then, most of the colonies in the South Pacific and some of the smaller islands in the Caribbean have become independent, with only a few tiny places, typically those valuable as naval or air bases, remaining.

However, the end of the empire was far from bloodless, with ruthless anti-insurgency practiced from Kenya to Malaya particularly in the 1940s and 1950s.

Even after Macmillan's official change in policy, there have been voices calling for preservation of the empire. Some claim that governed people were happier or better off during the Empire, such as by pointing to the many civil wars and coups in African countries: these countries were often poor, left with little infrastructure, constructed without regard for ethnic divisions, subject to interference by more powerful nations, and turned into pawns during the Cold War. Other times, the interests of white settlers are considered more important than the needs of black populations.

League of Empire Loyalists[edit]

This was formed in 1954 to oppose independence for the former empire, but the fact that it was founded by prominent fascist A. K. Chesterton should indicate its real intentions. Members included Colin Jordan, later head of the openly neo-Nazi National Socialist Movement, and John Tyndall, who was later head of the National Front.[133][134] In 1967 the rump of the movement merged into the newly-formed National Front.[135][136]

They campaigned on a range of subjects, pro-empire and anti-internationalist: their tactics focused on interrupting public meetings and disrupting protest marches, but extended to vandalism. Their enemies included:

- Those calling for an end to the empire. This includes heckling a meeting of the Movement for Colonial Freedom in 1956.[137] In July 1957 two protestors from the League, including John Bean (later of the first incarnation of the British National Party) infiltrated a reception for Commonwealth leaders at St James's Palace, London.[138]

- Opponents of the apartheid regime in South Africa. They interrupted a 1956 protest against apartheid.[139] In June 1960 they heckled a speech by the Bishop of Johannesburg, Ambrose Reeves, a prominent critic of the apartheid regime.[140]

- Liberal media. In 1955 they challenged the BBC for anti-Empire bias following remarks made by Gilbert Harding.[141] They vandalised the home of TV personality Malcolm Muggeridge.[142]

- Harold Macmillan's Conservative Party, with several meetings disrupted, including the 1958 Conservative Party conference[143]

- The United Nations, tearing down a UN flag in October 1955.[144]

- Communist Russia, objecting to Khrushchev's 1956 visit to London.[145]

- High taxes. In November 1956 they teamed up with organisations including the Croydon Magna Carta Society, the Elizabethan Party for Great Britain and the Empire, and the Cheap Food League to protest taxation.[146]

They even attempted politics: they stood candidates in a 1957 byelection in North Lewisham and in 1959 in Bournemouth East.[147][148]

Conservative Monday Club[edit]

This organisation was founded in 1961, following Macmillan's speech, to defend the empire.[149] It supported South Africa and later white Rhodesia (see below), and advocated voluntary repatriation for non-white immigrants in the UK. During the 1980's it ended up being allied with the South African Conservative Party, which was created to preserve all aspects of apartheid in a time when the position became increasingly more untenable.

Rhodesia[edit]

Ian Smith, PM of Rhodesia, declared independence from the UK in 1965, and set up a government system which effectively preserved power for the white minority. This was strongly supported by some right-wingers in the UK, including the Monday Club and the ironically-named Freedom Association. Since the official independence of the country as Zimbabwe, the country has become an economic disaster and human rights nightmare, leading to a lot of concern from the right-wing press about the few white people left behind, and notably very little concern from those same people about the black majority population.

Niall Ferguson[edit]

Particularly in his book Empire, Ferguson argued for the merits of the British Empire, focussing on decent Victorian administrators and occasional moments of idealism, and ignoring the rapacity of the British slave trade.[150] Conservative education secretary Michael Gove called on Ferguson's help to write a curriculum for English history, which suggests some sympathy in government.[151]

New Labour[edit]

British politician Gordon Brown made several remarks in favour of the empire, saying "the days of Britain having to apologise for its colonial history are over" and saying Britain should have been proud of its empire.[152] Tony Blair reportedly held similar beliefs but was more circumspect about expressing them. With both men, a strong belief in humanitarian intervention and Britain's role in imposing peace in places such as Iraq apparently led to their sympathy for the imperial mission.[153]

See also[edit]

- French colonial empire

- German Empire

- History of Black people in Britain

- Manifest destiny

- CANZUK, jokily referred as Empire 2.0

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Rule Britannia. Historic UK.

- ↑ Richard Turnbull (colonial governor) Wikiquote.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on List of largest empires.

- ↑ The British Empire At Its Territorial Peak Covered Nearly The Same Area As The Moon. Brilliant Maps.

- ↑ Jackson, Ashley (2013). The British Empire: A Very Short Introduction. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-960541-5. p. 5–6

- ↑ Russo, Jean (2012). Planting an Empire: The Early Chesapeake in British North America. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0694-7. p. 15

- ↑ Capitalism and extreme poverty: A global analysis of real wages, human height, and mortality since the long 16th century

- ↑ Jenks, Edward (1918). The Government of the British Empire. Little, Brown, and Company.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Crown colony.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 English Administration of the Colonies. Lumen Learning.

- ↑ David S. Lovejoy, "Equality and Empire The New York Charter of Liberties, 1683," William and Mary Quarterly (1964) 21#4 pp. 493-515 in JSTOR.

- ↑ Joseph E. Illick, "The Pennsylvania Grant: A Re-Evaluation," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1962) 85#4 pp. 375-396 in JSTOR

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Chartered company.

- ↑ Chartered company. Britannica.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 See the Wikipedia article on British protectorate.

- ↑ Roberts, J. M., The Penguin History of the World (London: Penguin Books, 1995, ISBN 0-14-015495-7), p. 777

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Balfour Declaration of 1926.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Statute of Westminster 1931.

- ↑ Dominion. Britannica.

- ↑ Mandate. Britannica.

- ↑ Glenn, Keith (1944). "Captain John Smith and the Indians". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 52 (4): 228–248. JSTOR 4245316.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 The Third Anglo-Powhatan War. Native American Netroots.

- ↑ First Anglo-Powhatan War (1609–1614). Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ↑ Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622–1632).Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ↑ James, Lawrence (2001). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-312-16985-5. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ↑ Facts About the Maryland Colony. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ Chart of the 13 Original Colonies. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on New Sweden.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on New Netherland.

- ↑ Hudson's Bay Company. Britannica.

- ↑ Rupert's Land. Britannica.

- ↑ French and Indian War/Seven Years’ War, 1754–63. US State Department.

- ↑ Proclamation Line of 1763, Quebec Act of 1774 and Westward Expansion. US State Department Office of the Historian.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Kalinago Genocide of 1626.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Sean (2000). To Hell or Barbados. Dublin: Brandon, O'Brien Press. pp. 66, 137, 148, 173, 176, 202. ISBN 978-0-86322-287-0.

- ↑ Ali, Arif (1997). Barbados: Just Beyond Your Imagination. Hansib Publishing (Caribbean) Ltd. pp. 46, 48. ISBN 1-870518-54-3.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Barbados Slave Code.

- ↑ East India Company. Britannica.

- ↑ Fort Saint George. Britannica.

- ↑ Carnatic Wars. Britannica.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle of Plassey.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Anglo-Mysore Wars.

- ↑ Markovits, Claude (2004), A history of modern India, 1480-1950, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-84331-152-2 p. 271

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Princely state.

- ↑ Cartwright, Mark. "Indian Princely States". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara Daly; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A concise history of modern India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9 p. 56–91 "Chapter 3: The East India Company Raj, 1772–1850"

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Waterloo Creek massacre.

- ↑ Egan, Ted (2003). The Land Downunder. Grice Chapman Publishing. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-9545726-0-0.

- ↑ [https://web.archive.org/web/20040618142015/http://encarta.msn.com/media_701508643/Smallpox_Through_History.html Smallpox Through History]. Archived.

- ↑ Attwood, Bain; Foster, Stephen Glynn (2003). Frontier Conflict: The Australian Experience. National Museum of Australia. ISBN 978-1-876944-11-7, p. 89.

- ↑ Attwood, Bain (2005). Telling the truth about Aboriginal history. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-577-9.

- ↑ Jupp, James; Director Centre for Immigration and Multicultural Studies James Jupp (2001). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-521-80789-0.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Federation of Australia.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Crown Colony of Malta.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on United States of the Ionian Islands.

- ↑ Winston Churchill. Wikiquote.

- ↑ Greaves, Adrian (17 June 2013). The Tribe that Washed its Spears: The Zulus at War (2013 ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. pp. 36–55. ISBN 978-1629145136.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Great Trek.

- ↑ Collins, Robert; Burns, James (2007). A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 288–293. ISBN 978-1107628519.

- ↑ The Strait of Malacca – a historical shipping metropolis. World Ocean Review.

- ↑ Malaya Colony. The British Empire.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Straits Settlements.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Federated Malay States.

- ↑ British in Malaysia. Facts and Details.

- ↑ The Story of Colonisation in New Zealand. The Culture Trip.

- ↑ A Brief History of Waitangi Day. The Culture Trip.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on New Zealand Wars.

- ↑ Martin, Laura C. (2007). Tea: the drink that changed the world. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3724-8. p. 146–48

- ↑ Janin, Hunt (1999). The India–China opium trade in the nineteenth century. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0715-6. p. 133–34

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 See the Wikipedia article on British Hong Kong.

- ↑ George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston. Wikiquote.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Doctrine of lapse.

- ↑ Brown, Judith M. (1994), Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 480, ISBN 978-0-19-873113-9

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ Marshall, P. J. (2001), "1783–1870: An expanding empire", in P. J. Marshall (ed.), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, Cambridge University Press, p. 50, ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Government of India Act 1858.

- ↑ Adcock, C.S. (2013), The Limits of Tolerance: Indian Secularism and the Politics of Religious Freedom, Oxford University Press, pp. 23–25, ISBN 978-0-19-999543-1

- ↑ Morefield, Jeanne (2014), Empires Without Imperialism: Anglo-American Decline and the Politics of Deflection, Oxford University Press, p. 189, ISBN 978-0-19-938725-0 Quote: "The 'Indian Empire' was a name given to those areas in the Indian subcontinent both directly and indirectly ruled by Britain after the rebellion; the British issued passports after 1876 under that name."

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on British rule in Burma.

- ↑ [1]. How Britain stole $45 trillion from India

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Rebellions of 1837–38. Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Durham Report. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Constitution Act, 1867.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Suez Canal Company.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 The Suez Canal: A Man-Made Marvel Connecting the Mediterranean and Red Sea. Marine Insight.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on British Conquest of Egypt (1882).

- ↑ Knight, Ian (2003). The Zulu War 1879. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-612-6. p. 8

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Battle of Isandlwana.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Colony of Natal.

- ↑ South African War. Britannica.

- ↑ The Concentration Camps of the Anglo-Boer War. War History Online.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Orange River Colony.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Transvaal Colony.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on South Africa Act 1909.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Basutoland. British Empire.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Basutoland.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Botswana History. Victoria Falls Guide.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Botswana: British protectorate. Britannica.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Cecil Rhodes. Wikiquote.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 We don't want to erase Cecil Rhodes from history. We want everyone to know his crimes. The Telegraph.

- ↑ Rhodesia. British Empire.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 Gold Coast. British Empire.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Mahdist Revolution. Black Past.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Mahdist War: Siege of Khartoum. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ Mahdist War: Battle of Omdurman. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 See the Wikipedia article on Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

- ↑ Southern Nigeria. British Empire.

- ↑ Northern Nigeria. British Empire.

- ↑ The Colonial Era (1882-1960). Harvard Religious Literacy Project.

- ↑ Nigeria’s Current Troubles and Its British Colonial Roots. The Globalist.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on History of Zanzibar.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Kenya. British Empire.

- ↑ Uganda. British Empire.

- ↑ History of Sierra Leone. History World.

- ↑ Fyle, Magbaily C. (2006). Historical Dictionary of Sierra Leone. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 17-22. ISBN 978-0-8108-5339-3.

- ↑ Sierra Leone. Britannica.

- ↑ Sierra Leone. British Empire.

- ↑ British Mandate for Palestine. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- ↑ British Palestine Mandate: History & Overview. Jewish Virtual Library.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Emirate of Transjordan.

- ↑ Iraq. Britannica.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Iraq Mandate. British Empire.

- ↑ Tanganyika Mandate. British Empire.

- ↑ UN court rejects UK claim to Chagos Islands in favour of Mauritius, The Guardian, 28 Jan 2021

- ↑ Chagos Islands dispute: UK misses deadline to return control, BBC News, 22 Nov 2019

- ↑ UK will give sovereignty of Chagos Islands to Mauritius, Andrew Harding, BBC 3 October 2024

- ↑ How the sun will set on the British Empire for the first time in 200 years, Brooke Davies, Metro 4 October 2024

- ↑ How Queen Victoria left her mark on every corner of the planet. The Telegraph.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Victoria Land.

- ↑ https://youtu.be/6DQYu4iBNiQ

- ↑ https://youtu.be/DNM_8Yw5Ybw

- ↑ Far-right leader with a message of hate, Irish Times, 23 July 2005

- ↑ "Disturbances At Station", The Times, Friday, Apr. 20, 1956, Issue 53510, p 6. Via Gale.

- ↑ The National Front and the anti-fascist response in the 1970s, Warwick University Library

- ↑ "Britain and its Empire", Martin Pugh, The Oxford Handbook of Fascism, Edited by R. J. B. Bosworth, 2010.

- ↑ "Protests At Colonial Freedom Meeting", The Times, June 9, 1956, p4. Via Gale.

- ↑ Palace Reception Intruders, The Times, July 4, 1957, p 10. Via Gale.

- ↑ "Police Ban "Black Sash" Parade", The Times, June 28 1956, p3. Via Gale.

- ↑ Bishop Heckled By Empire Loyalist, The Times, June 24, 1960, p8. Via Gale.

- ↑ "News in Brief", The Times, Sept. 2, 1955, p 4. Via Gale.

- ↑ News in Brief, The Times, Oct. 25, 1957, p 5. Via Gale.

- ↑ Blows Alleged At Blackpool Meeting, The Times, May 15, 1959, p8. Via Gale.

- ↑ "Demonstrators Haul Down U.N. Flag", The Times, Oct. 24, 1955, p8. Via Gale.

- ↑ "Demonstration Foiled", The Times, Apr. 26, 1956, p6. Via Gale.

- ↑ "Crusade For Cuts In Spending", The Times, Nov. 14, 1956, p7. Via Gale.

- ↑ "News In Brief", The Times, Jan 3, 1957, p5. Via Gale.

- ↑ Unanimous Adoption Of 23-Year Old Candidate At Southend, The Times, Jan. 14, 1959, p8. Via Gale.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Conservative Monday Club.

- ↑ Linda Colley, "Into the belly of the best", 10 January 2003, The Guardian

- ↑ Seamus Milne, "This attempt to rehabilitate an empire is a recipe for conflict", 10 June 2010, The Guardian

- ↑ Benedict Brogan, "It's time to celebrate the Empire, says Brown", 15 January 2005, Daily Mail'

- ↑ Seamus Milne, "Britain: Imperial nostalgia", May 2005, Le Monde diplomatique