Germany

“”And now it's time for me to meet Europe's "cuddly teddybears"... the Germans. Germany as a country has only been in existence for just over a hundred years. But in that time they've started two world wars, they've had two military coups, they've been brought on the brink of starvation two times, and they've invaded almost all of their neighbours.

|

| —Jeremy Clarkson, Top Gear: Jeremy Meets the Neighbours.[1] |

Germany (German: Deutschland), officially known as the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland), is a country in Central Europe that has, in many ways, been the primary engine of that continent's tumultuous modern history. The country is famous internationally for being the economic powerhouse of the European Union bloc and is one of its most influential members.[2] Germany's gifts to the world are its excellent beer, sausages, automobiles, classical music, and picturesque castles.[3] Unfortunately, the country wasn't always so nice, and it's thus also known for its violent history, rife with savage, horrific brutality, imperialism, religious wars, and not to mention the myriad crimes of the Nazi regime, the Holocaust, and the tense national division during the Cold War. Today, however, Germany is a democratic republic with its capital located in its largest city, Berlin. Thankfully, Germans of today are much more likely to smoke a joint than a Jew.[4] The country is strongly secular, with 55% of the population identifying as Christian but only 10% saying they are sure God exists.[5] About 6% of its people are Muslim, and 28% are atheist or agnostic.[5]

During classical antiquity, Germany was inhabited by various tribes noted for their violent warrior culture. They became persistent thorns in the side of the Roman Empire, eventually helping to bring about the downfall of the western half in 476 CE. The Germans remained divided and largely pagan until the Frankish ruler Charlemagne completed the bloody process of conquering them in 800 CE. Upon his death, the empire split, and the eastern half went on as East Francia, eventually evolving into the Holy Roman Empire under the rule of Otto the Great in 962 CE.

As suggested by its name, the Holy Roman Empire had a close institutional relationship with the Catholic Church, and its politics were dominated by struggles between the emperors and the popes who wanted to control or dick them over. Political struggles naturally escalated into violence, plunging the empire into frequent civil wars and allowing ambitious local nobles to accumulate power for themselves at the expense of the empire's cohesion. Not a recipe for long-term success. Despite the empire's decentralization, it remained a significant force in European politics. German nobles and knights participated in various events in the Crusades, which helped Germany's borders spread further eastward. Over time, the Hapsburgs of Austria, one of the empire's noble families, came to dominate the empire's politics and consistently placed their rulers on its throne.

In 1517, German theologian Martin Luther started the Protestant Reformation by criticizing the Catholic Church. Local nobles saw the movement as an excuse to further distance themselves from the empire's central authority. Conflicts between Protestant princes and the Catholic empire were just as inevitable, bloody, and ultimately pointless as religious wars always are. They culminated in 1618 with the Thirty Years' War, a horrifying shit hurricane that killed millions, devastated Germany's economy, and destroyed most remaining elements of imperial authority and papal influence over imperial politics. Afterward, Austria focused on growing its own domains outside of the empire while various German states started to grow unchecked.

From 1740, the Kingdom of Prussia, which ruled from Berlin, became the dominant power in northern Germany thanks to its extreme militarism. It repeatedly clashed with Austria before teaming up with them against Napoleon Bonaparte. However, they were unsuccessful in stopping him, and the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806. After Napoleon's downfall, Austria and Prussia remained great powers and grappled with each other because that's just what powerful countries do.

Amid the modern trends of the early 19th century, the question of German unification arose: the nationalist idea that the various independent German states left behind by the old empire should be united into a single German state. Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck eventually made it happen, first by beating up Austria to control southern Germany and exclude Austria from unification, then by waging a short and brutal war against France in 1870 to solidify Prussia's status as a superpower and convince the German states to accept annexation. Over the defeated French in Versailles, Bismarck and the Prussian king proclaimed the German Empire, which charted a conservative path under Bismarck, establishing universal healthcare to keep the population pacified. It eventually joined the Scramble for Africa while throwing in some native genocides for extra measure.

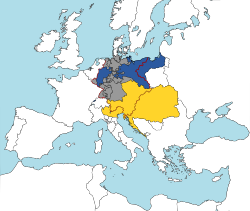

The German Empire was ultimately dismantled after World War I, leading to a period of political and economic crisis and a failed democracy called the Weimar Republic. The Austrian-born Adolf Hitler rose to prominence during this period after participating in a dumb failed coup and writing a shitty book, eventually seizing power and turning Germany into Nazi Germany while annexing a bunch of its neighbors. He then launched Germany into World War II, devastating Europe and committing genocide against Jews, Roma, and other groups of people he hated for existing. Hitler's stupid war backfired, leaving Germany stripped of its eastern possessions and split between the Soviet Union's puppet of East Germany and the Western-aligned democracy of West Germany.

Some nerve-wracking brinksmanship and hostile relations later, and East Germany reunified with the west in 1990 after the general collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Since then, modern Germany has focused on reintegrating its eastern regions while building its economy. Unfortunately, it's been challenged by a resurgent far-right and problems associated with accepting Muslim refugees from the Middle East.

History[edit]

Antiquity[edit]

Germanic tribes[edit]

The Germanic tribes, probably from along the Baltic coast, spread throughout central Europe during the classical era. By the time of Julius Caesar, they had reached the frontiers of the Roman Empire, divided from it by the Rhine and Danube rivers.[6] The Romans reviled the Germans as warlike barbarians (probably a mostly fair assessment), and Caesar clashed several times with the Suebi tribe during his campaigns in France (then known as Gaul).[7]

The Romans repeatedly launched campaigns against the Germanic tribes, putting a great deal of effort into dominating them and keeping them divided while attempting to colonize the Rhineland. This proceeded bloodily but successfully for centuries until the effort was passed to Roman governor Publius Quinctilius Varus, a tyrant. He demanded heavy taxes from the Germans and punished dissent harshly.[8] As tends to happen, the oppressed people decided that they'd had enough of that shit and rebelled against the leadership of Romanized Germanic noble Arminius.[8] In 9 CE, Arminius' rebel force lured Varus and his Romans into the deep Teutoburg Forest, massacring the Romans completely despite being heavily outnumbered.[9] Although the Romans launched multiple punitive attacks against the Germans, they never again tried to conquer Germany.

The Romans had such a hard time with the Germans for many reasons. Germanic warfare focused on the love of the art, with multiple pagan gods exalting war and warriors.[10] In contrast to the Roman concept of pitched battles, Germans focused on raids to capture resources and show off their fighting skills. Germanic tribal chieftains were expected to be warriors with lots of machismo, and their followers fought for them in exchange for a share of loot and land.[10] This militant relationship eventually went on to become the basis of the more complex system of feudalism.

Migration period[edit]

Under pressure from many sides, the Western Roman Empire slid into a period of decline in the fourth and fifth centuries. The Germans, meanwhile, came under attack from migrating groups from Central Asia and their own population growth, which pushed the Germans to seek new homes in different regions of Europe.[10] This generally caused chaos across Europe, as them damn German illegal immigrants caused trouble wherever they went. The Frankish tribe conquered Gaul, Vandals and Visigoths pushed into Hispania, Saxons moved to Great Britain, and the Alamanni took over the Rhineland.[10] In all places, the Western Roman Empire was hacked apart by Germanic warriors who seized lands and built permanent settlements upon them.

This process spelled doom for the Western Roman Empire. This was especially true when the Franks took over Roman-held Gaul, which had been the primary agricultural production breadbasket of the empire.[11] Its loss wrecked the Roman economy and destroyed the empire's remaining ability to defend itself. In 476 CE, German chief Odoacer deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus, declaring himself the new leader of Italy and formally ending the Western Roman Empire.[12] Oh, those Germans.

Early Middle Ages[edit]

Under the Franks[edit]

Over in France, the Germanic Franks founded the first true Germanic state. Clovis I, the founder of the Frankish kingdom, converted to Christianity in 496 CE and began the conquest of central Europe by defeating the Alemanni.[13] Clovis attributed the victory to divine intervention, becoming a zealous Catholic. He and his successors sent priests from the church into Germany, most notably Winfrid, who became known as Saint Boniface for shaping the nature of German Catholicism and establishing a political alliance between the Franks and the Catholic Church.[14]

In 768 CE, Charlemagne inherited the Frankish crown and used much of his reign to extend the borders of the Frankish kingdom outwards to encompass most of Germany. Charlemagne's conquests were brutal, especially against the pagans of northern Saxony, many of whom he had massacred in retaliation for resisting him.[15] What a guy. For his service to the Catholic Church, Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of the Franks by the pope himself in 800 CE, choosing to rule his empire from the German city of Aachen. He commissioned one of the world's oldest cathedrals in that city, which formed part of his palace and became his final resting place.[16]

After Charlemagne's death, his empire was divided among his son, as was the custom of the era and known to all Crusader Kings players who've had their games ruined by a bad succession. The heirs promptly warred against each other until 843 CE, when the empire was finally divided for good between West Francia (which would become France) and East Francia (which would become the Holy Roman Empire).[17]

The First Reich[edit]

| —The obligatory Voltaire quote[18] |

Formation and papal conflicts[edit]

“”The Pope is ready to make some more emperors, of the Roman Empire. The Holy Roman Empire. It's actually Germany, but don't worry about it.

|

| —Bill Wurtz[19] |

For usual dynastic reasons, the Liudolfing dynasty replaced the Carolingians as the rulers of East Francia. King Otto I married the widowed Queen Adelaide of Italy, folding most of northern Italy into his German realm.[20] Since they had a good relationship, the pope crowned Otto as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Charlemagne, establishing Germany as the successor to the Western Roman Empire and ensuring that the papacy would be in charge of the succession of its rulers.

That last part was to be the problem. Since Holy Roman Emperors were elected from among a few choice members of the German nobility per Germanic tradition, the empire passed to the Salian dynasty, which didn't quite get along with the popes and had the Liudolfingers. The Salian emperors clashed with the papacy over investiture, whether the popes or royal rulers had the right to appoint bishops. Investiture was serious business since the bishops would hold church estates and the massive wealth and power that came with them. To maintain authority over church wealth, the popes wanted to ensure that only they could appoint bishops.[21]

In 1075, Pope Gregory VII composed the "Dictatus Papae", which declared that the papacy was the sole universal authority and had the legal power to remove the Holy Roman Emperor.[21] Emperor Henry IV didn't like that, and the pope retaliated by calling supporters from among the German faithful and starting a civil war in the Holy Roman Empire that lasted for decades. The bloodshed continued until 1122, when emperor Henry V signed the Concordat of Worms, effectively agreeing to leave the pope's power alone.[22] The wars, largely carried out by nobility against the emperor, permanently ensured that the empire would remain a decentralized and hollow shell.

Crusades and expansionism[edit]

“”[We swear] to go on this journey only after avenging the blood of the crucified one by shedding Jewish blood and completely eradicating any trace of those bearing the name 'Jew'.

|

| —Godfrey of Bouillon, one of the leaders of the First Crusade[23] |

Despite that minor issue of intentionally tearing their country apart with a civil war, the Holy Roman Emperors remained loyal to Catholicism. They joined the Catholic Crusade effort to take Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the Muslims who lived there. Emperor Conrad III went forth in person during the Second Crusade, although his entire army was almost immediately destroyed in a massive flood on the way there.[24] Ouch. His successor, Frederick Barbarossa, managed to win a few battles during the Third Crusade, eventually losing against the Kurdish ruler Saladin and dying while trying to cross a river.[25] Water was the bane of German crusaders, apparently.

The Crusades and the general idea of Christian holy war became good ideological justifications for pushing the empire's frontiers eastwards. German princes used offers of reduced taxes and manorial obligations to encourage peasants to colonize much of what is now Pomerania, Saxony.[26] When this inevitably started conflicts, the empire overpowered the Slavic rulers with their more organized military might, bringing areas like Bohemia, Pomerania, and Silesia into the empire's fold.

German Crusaders also targeted the Baltic Coast, most significantly under the banners of the Teutonic Order. Beginning in 1233 CE, the Teutonic Order conquered Slavic pagans in Prussia, all but exterminating the native population, then built a shitload of castles to rule the region as their personal property.[27] From that point, the region of Prussia became a militarized German stronghold, which would have massive consequences later on.

While the Germans benefited from the Crusader craze, another group of people living in the empire did not. Jews, who had long been the target of antisemitism from Medieval Europeans, were targeted with pogroms by German and French Crusader wannabes who decided to wage holy war against their neighbors.[28] These events are considered the first expression of the deep European hatred towards Jews that would culminate in the Nazi genocide.[29]

Early Hapsburg era[edit]

The Golden Bull of 1356 made the empire's decentralized nature official, formalizing the tradition of having seven electors from the nobility choose the next emperor and granting extensive rights to local princes.[30] With the empire so broken up amongst largely autonomous local nobles, the emperor became more of a first-among-equals than anything else. It was this situation that the Hapsburg dynasty of Austria inherited. As a result of the empire's fragmentation, the Hapsburgs tended to look elsewhere to grow their power, placing relatives on the thrones of countries like Spain and Hungary.

Still, the empire prospered during this time, even after the Black Death. Its location at the center of Europe ensured that its rivers and coasts hosted a vibrant international trade between northern and southern Europe and the east and the west. The wealth that this trade brought made Germany an early center for manufacturing, and its population began to urbanize and form cities along major routes. The wealthiest cities were dominated by an oligarchic merchant elite, and many of these cities grouped together in the Hanseatic League because rich assholes got to stick together.[30] The league became a serious military power, able to take down Denmark in a war, and its existence threatened the traditional dominance of landed hereditary nobility.

Germany's growing wealth and population also brought it into the German Renaissance, a cultural and artistic movement focused on classical knowledge that spread from Italy.[31] Principalities and cities of the empire used their wealth to undergo a construction spree, building castles and buildings all over the damn place. This was especially true of the Hanseatic Cities, which wanted to demonstrate their wealth to impress the landed nobles and gain some political status. Along with culture and art, many German thinkers started to embrace the ideals of humanism, a similar consequence of the Renaissance.

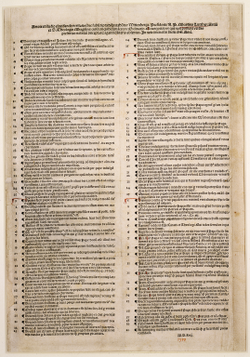

Economic and population growth was soon combined with intellectual development as well. In 1436, German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg began designing a machine that used mobile, reusable type blocks in a printing press, allowing for the rapid production of different pages of text to produce books.[32] Until then, European texts had to be written by hand, a massive carpal tunnel syndrome-inducing pain in the wrist/ass. Of course, this being Medieval Europe, the printing press was primarily used to print Bibles and religious works but would eventually pave the way for the rapid spread of information and propaganda.

Protestant Reformation[edit]

“”All of Germany is in an uproar. Nine-tenths shout out the battle cry 'Luther,' and the remaining ten percent, if they are indifferent to Luther, express the slogan 'Death to Rome.'

|

| —Aleander, papal legate, 1520[33] |

The Holy Roman Empire was a hotbed of discontent on the eve of the Reformation. The wealthy bourgeoisie in northern Germany was discontented with how little respect their riches earned, and regional princes wanted to strengthen their noble rights and further decentralize the empire.[34] Rural peasants, meanwhile, were starting to feel the effects of sustained population growth, with food becoming more expensive and wages starting to stagnate.

In 1517, Martin Luther, a professor of theology at Wittenberg University in Saxony, began publishing some pamphlets expressing disillusionment with the growing wealth and resulting corruption within the Catholic Church. The event which pushed him over the edge was the announcement that the Church hoped to sell a shitload of indulgences (a note that says "don't worry about that sin you just did, bro")[35] to finance the construction of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City.[36] To Luther, it seemed pretty fucked up to twist theology to raise money for a kickass new building in a religion that was supposed to prize moderate living and charity. The Ninety-Five Theses, his first pamphlet on the matter, laid out a thorough critique of the practice of indulgences as corrupting both the faith of the people and the integrity of the church. This message resonated with the discontent people of northern Germany, and the printing press helped spread it all over the place. It was basically a perfect storm.

As you might expect, Church authorities told Luther to shut his fucking mouth or else be excommunicated. Luther refused to shut up and was immediately met with horrible consequences. After his excommunication, the Holy Roman Emperor declared Luther an outlaw, banned his writings, and called for either his arrest or murder.[37] However, Luther's ideas had won some support from the Holy Roman Empire's princes, especially those who wanted to use them as an excuse to push back against the emperor's authority. In a stunt worthy of a heist movie, Frederick III, the Elector of Saxony, arranged for Luther to be intercepted by agents disguised as highway robbers and secreted away to Wartburg Castle for safekeeping.[38] From his hideout there, Luther translated the New Testament into German and distributed more writings attacking the Church on matters including veneration of saints, relics, and priestly celibacy.[39] But Luther also published a shitload of antisemitism, most notably "On the Jews and their Lies", which called for the expulsion of Jews and the burning of synagogues.[40] Oh boy, what bad things could German antisemitism cause?

Lower class uprisings[edit]

The revolutionary nature of Luther's ideas tipped the tenuous balance of German society. In 1522, the Knights' Revolt broke out, pitting impoverished lower nobles who had accepted Protestantism against the emperor and Church they resented.[41] The uprising was short and put down within a year, but it was a bad sign of violence yet to come.

In 1524, the German Peasants' War exploded. Remember those peasants who were having a hard time affording their food? Yeah, a hungry person is only a step away from becoming a rebellious person. The peasants were most angry at the Catholic Church, which Luther had exposed as corrupt and thrived by taxing local nobility, which in turn imposed heavier taxes on the peasants.[42] Peasant demands were myriad, including lower taxes, allowing congregations to choose their pastors, stopping land enclosures that cut off fish and game access, ending serfdom, and establishing a fairer justice system.[42] Pretty reasonable demands, but the nobles and Church weren't going to have any of that shit. The rebels seized the town of Heilbronn, where they formed a parliament, and Würtzburg, the seat of a Catholic bishop.[43]

Ultimately, the peasants could not overcome the military superiority of the much wealthier and more connected nobility. Luther also opposed the movement, writing that the peasants had a religious obligation to stay nice and obedient and that the nobles had every right to kill them in retribution.[42] And kill them the nobles did, massacring some 100,000 people and punishing them with even more repressive laws.[42]

Escalating religious conflicts[edit]

With increasing numbers of German princes and peasants joining the Protestant movement, religious conflict in Germany became inevitable. After all, when you think you have the only correct interpretation of God's word, surely everyone else must be brought to the truth by force. The various emperors during this time were furious that their imperial authority was being defied by the growing alliance of Protestant princes. To protect themselves, the Protestant nobles formed a military pact called the Schmalkaldic League, the first genuine military threat posed by the Protestants.[44] However, its members' competing personalities and goals meant that the alliance was unstable, and it was predictably smashed by the emperor in a short war in 1546.[45] The Catholics presumably thought things were over at this point, but the fact that religious tensions had caused an actual war between rulers only inflamed hatred even more. Sure enough, the Second Schmalkaldic War blew up in 1552, although the Protestants could force the emperor to negotiate with them this time.[46]

To their credit, the various rulers in Germany realized that the constant religious wars weren't going to end well for anyone. The Holy Roman Diet assembled at the command of the emperor. It proclaimed the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, allowing German princes to choose Catholicism or Lutheranism as their faith in the hopes of everyone getting the fuck along.[47] Unfortunately, people couldn't just get the fuck along.

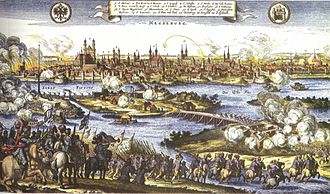

The peace almost immediately came apart when Catholic prince-bishops started converting to Protestantism. That was a major problem because they generally refused to give up their Church-given land and wealth, which was an enormous problem for the Church and faithful Catholics. When the prince-bishop of Cologne tried to do that in 1583, Catholic princes attacked him to keep Cologne in Catholic hands.[48] During the fighting, the Catholic forces surrounded the city of Neuss. They destroyed it with artillery fire, destructive house-to-house fighting, and plundering, killing an estimated 4,000 civilians.[49] Catholic forces also massacred hundreds of men, women, and children after seizing the fortress of Godesberg.[50] It also didn't help that Calvinists were explicitly left out of the peace.

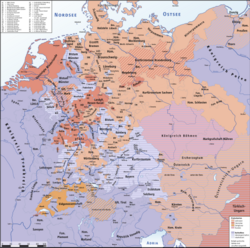

In 1608, in response to further inter-religious violence, many of the Protestant powers led by the Palatinate and Brandenburg formed the Protestant Union, an even larger coalition of both Lutheran and Calvinist states, to protect against the Catholics.[51] A year later, it intervened in the War of the Jülich Succession, pitting them against both the emperor and Spain in the question of which religion's candidate would inherit the empty throne of the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg.[52] Another bloody round of fighting later, Catholics and Protestants hated each other more than ever. Germany settled into an atmosphere of religious paranoia in which princes carefully monitored their populations for signs of religious dissent.[53] For an example of how absurd things got, German Protestants refused to accept the Gregorian calendar for decades because they were afraid that the Catholics were somehow plotting to steal time.[53] The Holy Roman Diet also couldn't get anything done because the Calvinists and Protestants liked to storm out whenever they didn't get their way, and the Catholics were morally opposed to working with them.

Thirty Years War[edit]

Germany's religious troubles occurred against a backdrop of general chaos in Europe. France endured the French Wars of Religion![]() against the Huguenots, decades of conflict, and mass murder which cost the lives of three million people.[54] Spain and the Netherlands duked it out over Dutch independence, a conflict aggravated by their religious differences and escalating into the total destruction of multiple cities. England was also about to fall into the English Civil War, which would draw in the rest of the British Isles.

against the Huguenots, decades of conflict, and mass murder which cost the lives of three million people.[54] Spain and the Netherlands duked it out over Dutch independence, a conflict aggravated by their religious differences and escalating into the total destruction of multiple cities. England was also about to fall into the English Civil War, which would draw in the rest of the British Isles.

In this atmosphere of religious crisis, Ferdinand II became the new Holy Roman Emperor and was widely known as a zealous Catholic and an oppressor of Protestants.[55] When he tried to oppress Protestants in Bohemia, a general Protestant uprising against his rule began in 1618, beginning the Thirty Years War. Although the emperor's armies smashed the initial revolt, just about every other Protestant state started jumping in. The Protestant states in northern Germany felt they had to join the revolt, but they were smashed by a Spanish army coming over from the Low Countries.[56] Denmark also tried to intervene on behalf of the Protestants, but they too fell to defeat. Emboldened by this military success, Ferdinand issued the Edict of Restitution, effectively confiscating most Protestant-held land in the empire.[57] The edict undermined the Catholic faction's victories by ensuring permanent opposition to them.

In 1630, Sweden also jumped in under its king Gustavus Adolphus, who sincerely wanted to protect the Protestants and seize some Baltic German land.[58] The Swedes and their allies were also bolstered by French funds. France, despite being a Catholic nation, hated the Hapsburg powers and hoped to undermine their power. After Gustavus' death, France joined the war directly and fought Spain and Austria for more than ten years before both sides finally agreed to a peace of exhaustion.

Throughout this fighting, the mercenary armies of the various belligerents constantly committed hideous crimes by pillaging everywhere they could and murdering anyone who resisted, regardless of which religion or which prince controlled the places they were destroying.[59][60] The armies moving back and forth resulted in vast swathes of Germany being totally razed, and the huge numbers of peasants being killed undermined Germany's ability to produce food. This caused a devastating famine, and the starving people became susceptible to numerous epidemics. The war ultimately killed five to ten million people through warfare, murder, disease, and famine.[61] Such human suffering was brought about by religious conflict.

The war lasted until 1648, when the exhausted parties finally came to the table and negotiated the Peace of Westphalia, which guaranteed limited religious freedoms for religious minorities in the empire, curbed the emperor's power even further, and allowed the various princes of the empire to choose their own state religions.[62]

Prussian ascendance[edit]

Thankfully, the Peace of Westphalia ended the empire's constant religious wars. On the other hand, the empire was dead, its central authority destroyed in the fires of war. From this point forward, the Austrian Hapsburg emperors largely neglected the empire's affairs in favor of growing the lands they held directly as the rulers of Austria.[63] Between the end of the Thirty Years' War and about 1740, the empire became a kickball to be hurled back and forth between the more centralized powers surrounding it, like France, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire.

Amid this chaos, several German imperial states grew more powerful without imperial limitations. The state of Brandenburg in northern Germany, ruled by the Hohenzollern dynasty, expanded significantly by merging with the lands of the old Teutonic Order in Prussia and taking northern territories from Sweden to gain a coastline on the Baltic Sea.[64] In 1701, Brandenburg's ruler declared himself King Frederick I of Prussia. The Kingdom of Prussia benefited from a long string of competent rulers, starting when Frederick I invested much time and money in expanding the podunk little town of Berlin into a modern capital that he hoped would rival Versailles.[65] To grow its population, Prussia invited religious refugees from other parts of the empire.[66]

Frederick William I succeeded him in 1713, having spent much of his life in the military. The new king's military background completely transformed Prussia, modernizing the tax system and stripping down the government to the point where Prussia became less a country and more, like the Teutonic Order before it, a military that happened to control a patch of land.[67]

In 1740, Frederick the Great took the Prussian throne. He gained that title by starting the War of the Austrian Succession as soon as he came to power, although he did it in a pretty shitty way. 1740 was also the year that the Hapsburg Austrian crown went to a woman, Maria Theresa. This was originally super illegal under traditional German law. When Maria Theresa was born, the then-reigning emperor enacted the "Pragmatic Sanction" to ensure that she could inherit the empire.[68] This was still broadly unpopular, and various anti-Hapsburg princes of the empire and abroad considered it a nice excuse to attack Austria. Frederick the Great roped France into the effort and then invaded. Prussia hit hard and fast, stole the large and rich province of Silesia from Austria, then quit the war early to leave France holding the bag.[69] Slick. As a result, the war ended in a stalemate with Maria Theresa still mostly in control, but Prussia had grown much bigger than before.

Enlightenment absolutism[edit]

“”Let us admit the truth: the arts and philosophy extend to only the few; the vast mass, the common peoples and the bulk of nobility, remain what nature has made them, that is to say savage beasts.

|

| —Frederick the Great to Voltaire.[70] |

Frederick and his nemesis Maria Theresa might have hated each other's guts, but they did have many ideas in common. Both embraced many ideas of the Enlightenment, a continental intellectual movement aimed at promoting reason, secularism, and science that gained much influence in the late eighteenth century. However, both rulers were also determined to use these ideas to bolster their own power rather than give any more say to the people. They both essentially believed themselves to be benevolent dictators.

Both Prussia and Austria reformed their administrations to make them as efficient as possible, and both Prussia and Austria strove to extend religious tolerance as much as possible in the era to attract migration and keep society harmonious.[71] Frederick became a close friend of French philosophe Voltaire and was generally enamored with French intellectual life.[70] On top of this, he allowed for the freedom of the press, encouraged the arts, and favored scientific and philosophical endeavors. Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II modernized the state by dramatically reducing the power of the Catholic Church over secular affairs and abolishing many of the old harsh punishments for crimes.[70]

Many of Germany's smaller states followed their example in the Enlightenment or went even further, such as the almost-democratic government adopted by Württemberg.[72] As a result, Germany was fairly well governed during this era despite the lack of democracy. All rulers hoped to avoid the religious chaos of the old ways. When the Catholic ecclesiastical state of Salzburg decided to expel Protestants in 1731, most German rulers, regardless of religion, were disgusted.[72] With the German states recovering from the religious wars, there was another great building spree following the Baroque tradition by German rulers wanting to demonstrate their expanded wealth and power.[73]

All of that being said, probably the greatest expression of rising German power during this period was the repeated partitions of Poland. In 1772, 1793, and 1795 Prussia, Austria, and Russia set aside their differences to gleefully seize Polish territory until there was nothing left.[74] Poor Poland, previously a major power, realized the consequences of being wedged between an increasingly powerful Germany and Russia.

French Revolution and Napoleon[edit]

Meanwhile, in France, the Enlightenment combined with longstanding societal resentment towards the king to create the French Revolution in 1789, in which the French people forcefully created first a constitutional monarchy and then an outright republic. The Enlightenment had been powerful in Germany, so the initial stages of the French Revolution were well-received by German intellectuals and the educated class.[75] However, things took a turn sharply for the worse when the Jacobins took over and created the First French Republic since they imprisoned France's queen Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette just so happened to be the Holy Roman Emperor's sister.[76] Oh shit.

In a rare show of unity, Frederick William II of Prussia and Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II issued the Declaration of Pillnitz in 1791 to support the French monarchy.[77] The French revolutionary government interpreted that as a threat and preemptively declared war on both parties, beginning the War of the First Coalition when the rest of the Holy Roman Empire rallied to defend the conservative order. In the hopes of threatening the revolutionary government into submission, Prussia and Austria promised to raze Paris and slaughter its inhabitants if anything bad happened to the king or Marie Antoinette.[78] The problem was that this promise came right after the royal family was guillotined, and the fear that the threat caused helped motivate the French armies into victory over the empire.

France also benefited from the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte, the brilliant general who seized power in France in a 1799 coup. When Napoleon declared himself emperor in 1801, Austria wouldn't stand for it since they were supposed to be the leaders of the Holy Roman Empire, which was supposed to be Europe's only Catholic empire.[79] Sometimes you just wanna feel special. These tensions over titles contributed to Austria's entry into the War of the Third Coalition in 1805. Unfortunately for Leopold, Prussia chose to remain neutral, meaning that much of the empire's military strength was sidelined.[80]

Austria and its remaining German allies got smashed easily by Napoleon, culminating in the Battle of Austerlitz, in which Napoleon defeated a much larger joint German-Russian force.[81] With the empire totally defeated, Napoleon decided to mercifully put the ill-begotten entity out of its misery. In the Peace of Pressburg, he reorganized it into a series of Napoleonic puppet states, grouping them into the "Confederation of the Rhine".[82] It also just so happened that Germany's internal borders looked much nicer. The Confederation of the Rhine then jointly seceded from the Holy Roman Empire, leaving it a hollow shell.[83] With Prussia not interested in preserving the empire either, Austrian emperor Francis II finally acknowledged reality and gave up on it.

German disunity[edit]

Post-Napoleonic order[edit]

Although Napoleon eventually met his downfall in 1815, his conquests left a broad legacy of change. He had improved public administration, greatly weakened the institutions of feudalism and trade guilds, and largely abolished ecclesiastical territories.[84] He had also broken the hopeless tangle of imperial disunity, reducing Germany from 300 states to a much more manageable 40. Germany had been dragged kicking and screaming into something resembling modernity.

These changes were largely maintained by the Congress of Vienna, a continental peace conference assembled to figure out what the fuck to do after the European order had been so thoroughly shattered by Napoleon[85] (it should be noted that in German, this had the amusing name of Wiener Congress). The primary agenda was to figure out how to restore the conservative tradition of monarchies.

Rather than reestablish the HRE, which would have been a colossal pain in the ass, the delegates at Vienna decided that Germany would be grouped into an entity called the German Confederation. The states within it would technically be sovereign, but the confederal government (which would always be led by an Austrian) would have some say in their internal affairs. Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich promptly used the Confederation to suppress any further revolutionary threat by imposing censorship regulations and keeping a close eye on German universities.[86] This did much to suppress German intellectual and cultural life.

Although not the leader of the Confederation, Prussia benefited greatly from the Congress of Vienna and its new European order. In exchange for handing some relatively low-population Polish territories to Russia, Prussia gained the Rhineland and Westphalia, densely-populated regions rich in natural resources like coal and iron.[87] These parts of Germany quickly became at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution in continental Europe, thus turning Prussia into a European superpower.

Rising nationalism[edit]

“”The first, original, and truly natural boundaries of states are beyond doubt their internal boundaries. Those who speak the same language are joined to each other by a multitude of invisible bonds by nature herself, long before any human art begins; they understand each other and have the power of continuing to make themselves understood more and more clearly; they belong together and are by nature one and an inseparable whole.

|

| —Johann Gottlieb Fichte, To the German Nation, 1806.[88] |

Alongside Napoleon's administrative and civil reforms, there was also a much greater societal push toward nationalism, specifically focused on German unification. Napoleon's easy victories over the disunited Holy Roman Empire convinced many Germans of the need for strength through unity. In northern Germany, nationalism gained a religious component, with intellectuals claiming Martin Luther as the first German nationalist and festivals being held burning works by Austrian Catholics as reactionary bunk.[89] (Germans do like their book-burnings). Nationalism also gained traction with wealthy business owners, who spent the 1820s pushing for a customs union in the Confederation and hoped that an economically integrated Germany could match the industrial might of the United Kingdom.[90] On the other hand, poor farmers were generally left out of discussions, as they were considered too stupid.

Revolutions of 1848[edit]

Rising nationalist sentiment hit a boiling point in 1846 when the European potato crop failed, causing food prices to skyrocket and causing the economy to do the opposite.[91] As tends to happen, hungry people became the breeding ground for revolution. In 1848, an uprising among the famously restless French forced French king Louis Philippe I to abdicate and flee to the UK. The success there inspired similar movements in Germany.

Revolts broke out in Vienna and Berlin, initially with little organization or goal. However, they eventually solidified around the goal of German unification when liberal activists created the Frankfurt Assembly in Frankfurt am Main to create a nationally-elected parliament.[92] In 1849, the assembly produced a democratic constitution and offered to help crown King Frederick William IV of Prussia as the emperor of a united Germany. Unfortunately, the king was far too conservative to accept a crown from anyone save the noble princes of Germany.

The Prussian king instead created his own constitution based on the principle of absolute monarchy, and he used military force to roll back the revolutionary tide and shut down the Frankfurt Assembly.[93]

Socialism and industry[edit]

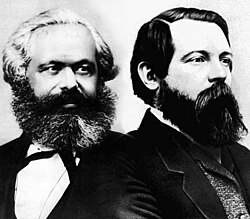

Remember how Prussia got the Rhineland, a region they then started exploiting for industry? Well, in 1818, a certain Karl Marx was born there, in the city of Trier. His upbringing in an industrial area, combined with the experience of having one of his liberal mentors subjected to surveillance and arrest, caused him to embrace the ideals of socialism and then communism.[94] Marx eventually went into exile, living in Paris and then Brussels, Belgium. In Brussels, he studied history and outlined what came to be known as the materialist conception of history. He then met close collaborator Friedrich Engels, formed an organization to link socialist-minded thinkers around Europe, and helped found the Communist League in London.[94] The League then asked Marx to write its manifesto, which he wrote and published with Engels in 1848 as the Communist Manifesto.

Engels, meanwhile, took part in the 1848 uprisings and was exiled to Switzerland for his trouble.[95] After Marx died, Engels helped edit Das Kapital, and he became a leading figure in international socialism. Engels helped preserve the socialist movement in Germany during the post-revolutionary period, where conservative rulers cracked down on political dissent. Marxist thought remained relevant in large part due to Germany's rapid industrialization and deteriorating social conditions that came with it.

The German Question[edit]

The Revolution of 1848 also brought about the German Question, as the Frankfurt Assembly had toyed with the idea of having Austria's ruler unite Germany instead. Supporters of the Großdeutsche Lösung ("Greater German solution") favored unifying all German peoples, while supporters of the Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Little German solution") believed instead that German unification should exclude Austria entirely.[96] The latter option was favored by Prussia, who wanted to dominate any potential German state and viewed excluding Austria as the easiest way to ensure that would happen.[97] The German Question would shape the entire effort to unite Germany.

German unification[edit]

“”There is, in political geography, no Germany proper to speak of. There are Kingdoms and Grand Duchies, and Duchies and Principalities, inhabited by Germans, and each separately ruled by an independent sovereign with all the machinery of State. Yet there is a natural undercurrent tending to a national feeling and toward a union of the Germans into one great nation, ruled by one common head as a national unit.

|

| —The New York Times, July 1, 1866[98] |

Bringing in Bismarck[edit]

“”The great questions of the time will not be resolved by speeches and majority decisions – that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849 – but by iron and blood.

|

| —Otto von Bismarck, speech to the Budget Committee of the Prussian Chamber of Deputies, 1862.[99] |

After the 1848 revolution, the Prussian public became far more in favor of the concept of a Prussian-led German unification. In 1862, the process began when King Wilhelm I of Prussia chose the relatively obscure nationalist diplomat Otto von Bismarck to lead the government. A staunch Protestant conservative, Bismarck hated the ideals of democracy, socialism, and Catholicism.[100] That being said, Bismarck was wise enough to realize that at least some of those popular concepts needed to be mobilized on his side if his dream of a powerful Germany would become a reality. Luckily for him, the hated state of Austria would prove to be a useful target to unite the German states against.

German unification was going to be a formidable task. The princes of the small German states quite liked being independent. Some of them, like Bavaria in the south, were fairly powerful in their own right. Bavaria also presented the problem of having the vast majority of its population follow the Catholic faith, which made it and the other southern German states reluctant to follow the leadership of the Protestant north. Not surprising given the, uh, history between them.

Beating up Denmark[edit]

In 1864, poor little Denmark became the first victim of Bismarck's aspirations after the King of Denmark's death sparked dispute over the succession.[101] Denmark had expanded south along the Jutland peninsula and gained control of two small German states, Schleswig and Holstein.[102] They had been assigned to Denmark by the British (who stuck their grubby noses into everything), but in an awkward manner that kept them mostly autonomous. When Denmark tried to tie them closer, Prussia and Austria both objected and jumped into a war on the claim that Denmark had violated the agreement and planned to begin oppressing the German minority population.[102]

As you might expect, Denmark didn't stand much of a chance. The real issue arose when Prussia and Austria sat down to decide who would get the spoils. Schleswig and Holstein happened to sit at a geographically important spot since a canal could be cut through the peninsula at the city of Kiel to bypass Denmark and link the Baltic to the Atlantic.[103] Austria and Prussia eventually agreed to take one state each. The question of resolving the Danish war raised the much broader question of which power would become the master of Germany.[104] Unable to talk it out, Austria and Prussia decided to have their final showdown.

The brother's war[edit]

This is where Austria's vast empire fucked them a little since Prussia managed to rope Italy into attacking Austria simultaneously to regain the Italian land that Austria had held for the last few decades.[105] Prussia began its war against Austria at the same time, in 1866, facing a pretty powerful alliance of Austria along with Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover, Württemberg, Hesse, and Baden.[106] The Austrian alliance had Prussia badly outnumbered.

Bismarck's diplomacy, however, won the day. By getting Italy into the fray, he could divert much of Austria's resources southwards, leaving Prussia free to deal with Austria's smaller allies.[107] Prussia's superior military, backed by industrial war production and rigid discipline, could overwhelm the divided allies. Prussia then invaded Austria, conducting a rapid campaign through Bohemia and winning a short series of victories over a handful of weeks to force Austria to the negotiating table.[108]

Bismarck kept his demands relatively light, excluding Austria from German affairs, taking control of Schleswig-Holstein, and folding all northern Germany into Prussia's sphere of influence.[109] Austrian ruler Franz Joseph was apparently not too upset by that, being totally disgusted with the shoddy performance of his German allies.[109] He said little when Prussia annexed its north German neighbors to become the North German Confederation. This dramatically boosted Prussian power and brought it one step closer to unification. Some states were annexed directly into Prussia, but others, like Saxony, were preserved as semi-autonomous units of the Confederation.

Beating up France[edit]

With all that accomplished, though, Bismarck had only finished the easy part. The hard part would be to get the stubborn Catholic southerners to willingly join Germany as well, as their cultural and religious differences were still significant.[110]

Bismarck's solution was to unite them with Prussia against a common foe. France proved to be a uniquely advantageous candidate, ruled by the impulsive and ill-tempered Emperor Napoleon III and already on unfriendly terms with most of the German states. In 1870, Bismarck decided to engineer a war by editing and leaking an internal message from the Prussian king, making it seem like he had insulted a French diplomat.[111] He (correctly) believed it would incite the French "like a red rag to a bull".[112] The edited telegram had exactly the result intended, as fiercely nationalist French crowds gathered in Paris to demand a war of honor against Prussia. Napoleon III was also assured by his advisers that the war would be quick and bolster his popularity with the French people.[113]

France thus declared war on Prussia over a diplomatic slight, thus casting France as the big meanie and Prussia as the put-upon defender forced into an unwanted war. Poor Prussia! With France launching a reckless attack on a German state, the southern Germans did as Bismarck hoped and rallied to support Prussia.

What followed was an unmitigated disaster for France, as while the war had been reckless on their part, it had been coldly calculated by Bismarck. Prussia used railroads and efficient organization to deliver 380,000 troops to the front lines in just over two weeks, while the French troops reached the front much later and were poorly equipped.[113] They completely overwhelmed the inferior French military and thoroughly defeated it in just two months. At the Battle of Sedan, France suffered a devastating loss, and Napoleon III was actually captured by the Prussian army.[114] The Germans then occupied much of northern France and laid siege to Paris, blowing a lot of shit up with their artillery.

The Second Reich[edit]

“”There is only one person who is master in this Empire and I am not going to tolerate any other.

|

| —Wilhelm II, 1891.[115] |

Three hurrahs for Germany![edit]

“”It's hard to be emperor under such a chancellor.

|

| —Wilhelm I, German Emperor, about Bismarck.[116] |

After Paris surrendered in the Franco-Prussian War, the final step in Bismarck's plan became a reality. Prussian troops paraded through Paris to rub salt in the wound while partaking in one of Germany's favorite activities. Prussian King Wilhelm I arrived at the Palace of Versailles, where the various German princes waited for him. Having hashed things out through 1870, the princes all participated in an 1871 ceremony in the Hall of Mirrors where they recognized Wilhelm I as the first Emperor of the German Empire.[117]

The empire became an aristocratic federation, with German princely states represented by an upper parliamentary house called the Bundesrat.[118] An elected Reichstag served as the lower house, representing the commoners with universal male suffrage and elections every five years.[119] Unfortunately, the Reichstag had little real power, lacking the right to draft legislation, dismiss the chancellor, or act as a check on the government's actions.[120] On the other hand, the emperor appointed the chancellor to lead the government, and he had the power to threaten the Reichstag into compliance because he had the right to call for snap elections. Bismarck was, as you would expect, the first appointed chancellor.

Social developments[edit]

Bismarck became the champion of conservatism within the German Empire, and he championed universal male suffrage out of a belief that the rural poor would reliably vote conservative.[121] That didn't happen. Instead, the poor voted more in line with their interests, favoring either the Center Party (which supported Catholic issues) or the social democrats. Bismarck angrily denounced them as "Reichsfeinde" or "enemies of the empire".[121] This was probably most directed at the Catholics since, as mentioned, Bismarck didn't trust the loyalty of Catholic Germans. His suspicions were seemingly confirmed when The Vatican declared in 1870 the doctrine of "papal infallibility", which he feared would make the Catholics even more likely to be loyal to the pope before the emperor.

Thus began the Kulturkampf, a political clash between Bismarck, his liberal allies of convenience, and the church.[122] Bismarck forbade priests from preaching politics at the pulpit in 1871; in 1872, he made all religious schools subject to state inspection.[122] To Americans, this just sounds like a basic separation of church and state, but these policies were strongly resisted by Germany's Catholics. Bismarck redoubled his efforts, dissolving the Jesuit order, severing diplomatic relations with the Vatican, and making the Church's ecclesiastical appointments subject to state authority.[122]

Although some major policies came out of it, the culture war completely backfired when the Center Party just kept winning more seats in the Reichstag. After tiring of the enterprise, Bismarck broke off his alliance with the liberals and instead focused his efforts on trying to limit the appeal of socialism. As before, the heavy-handed approach didn't work, as Bismarck discovered when he banned socialism from the press in 1874 and then more desperately banned social democracy and socialism outright.[123]

When that didn't stop socialists from winning seats as independent candidates, Bismarck focused on co-opting the socialist platform, hoping to bribe workers away from them. In 1883, Bismarck forced the Health Insurance Law, which created the first national healthcare system in the world.[124] Employers and employees paid into insurance funds, and the German government verified workers' enrollment by comparing employer records with fund membership lists, threatening employers of uninsured workers with fines. Bismarck followed that up with an accident insurance law in 1884. In 1889, Germany became the first country to implement an old-age social insurance program, which even the United States Social Security Administration acknowledges as one of its primary models.[125] Still, most socialists and social democrats recognized the ruse as a ruse.

Colonialism[edit]

Germany came late to colonialism due to, y'know, not existing before 1871. However, it was still a major power, and there was still time to edge it into the game. Germany's status was confirmed when Bismarck got to host the Berlin Conference in 1884 to ensure that the intense competition over African land wouldn't cause a European war that Germany would get sucked into. In Berlin, diplomats from the major colonial powers arrived to hash out who would get what chunks of Africa.[126][127] They effectively drew lines on a map.

Still, most of the best chunks of Africa, like Egypt, Nigeria, or the Congo, were taken already. Some regions they did get, like Cameroon and Togo, became giant plantations where Africans were forced to labor under deadly harsh conditions.[128] The German Empire also tried to eliminate local languages by banning them from schools and ordering that all official business be conducted in the German language.[129]

In German Southwest Africa, known today as Namibia, the Germans outright committed genocide against the Herero and Namaqua tribes for the crime of rising up to protest the Germans' use of all of the arid region's scarce water supply.[130] German colonial troops drove the tribes out of their homes and into the unsurvivable Namibian desert before confining them to concentration camps, where the survivors were either worked or beaten to death.[131] It is estimated that this led to the extermination of about 80% of the Herero and Nama populations.[132] In terms of hard numbers, that adds up to roughly 100,000 people murdered.[133] Seizing the opportunity, German scientist Eugen Fischer set up shop in the concentration camps to conduct evil medical experiments on the helpless prisoners.[133] Remind you of anything?

Enmity with France (and nearly everybody else)[edit]

“”That young man wants war with Russia, and would like to draw his sword straight away if he could. I shall not be a party to it.

|

| —Bismarck comments on Wilhelm II's foreign policy ideas.[134] |

Bismarck had recognized that Germany's position in the world was precarious due to its central location in Europe. France, for instance, would be an implacable enemy forever because of the humiliation they suffered in 1870 and the empire's annexation of the formerly French border region of Alsace-Lorraine.[135] France wanted that shit back, really bad. As a result, Bismarck's foreign policy focused on appeasing everyone and ensuring that the various powers of Europe were more friendly to Germany than they were to France.[136]

Then the old emperor died in 1888, followed just 3 months later by his son Friedrich III's death from cancer, and the throne went to his grandson Wilhelm II. Initially this was a relief to Bismarck, because Friedrich III had been a vehement liberal who wanted to establish a British-style constitutional monarchy. But Kaiser Wilhelm II, perpetually jealous of his cousins who reigned in other European monarchies, wanted to chart an aggressive and "glorious" path, and he quickly fired Bismarck when the old chancellor objected. His toxic and abrasive personality clashed with his cousin Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, and Wilhelm then impulsively decided to terminate the non-aggression treaty between them in 1890.[137] With Russia and France in the "fuck Germany" camp, the two powers signed an alliance in 1894.[138] Bismarck's worst fear of Germany being sandwiched between two enemies had been realized.

Wilhelm then ordered a vast expansion of the imperial German navy, explicitly stating that his intention was to compete with the British. In typically impulsive Wilhelm II fashion, this wasn't because Germany stood to gain from it but because he was jealous of his other cousin King George V's powerful navy. As you might expect, the British weren't a fan of this idea, and the two powers thus entered into an increasingly bitter naval arms race.[139] And just to make things even more dangerous, Wilhelm kicked off the Morocco Crises by interfering with French influence in the area in 1904, beginning a diplomatic fiasco that increased France's hatred and made the British even warier of Germany.[140] In the same year, France and the UK signed the "Entente Cordiale", promising to support each other's colonial ventures against Germany.[141] In other words, Wilhelm II was such an asshole that he managed to reverse about a thousand years of constant Anglo-French hostility.

Germany did, however, have a scarce few friends left in Europe. Bismarck had managed to repair relations with Austria and forge an alliance with them, an initiative that Wilhelm had not managed to screw up.[142] Wilhelm, for his part, had drawn closer to the Ottoman Empire, expanding political and economic ties by funding the Berlin–Baghdad railway to help integrate the Ottoman Empire and help Germany reach its eastern colonies.[143] The two powers were not quite allied, but they weren't acting all pissy with each other as Germany had been with almost everybody else.

World War I[edit]

Outbreak and deceit[edit]

“”To try and avoid such a calamity as a European war I beg you in the name of our old friendship to do what you can to stop your allies from going too far.

|

| —Tsar Nicholas II telegram to Wilhelm II on the eve of the war.[144] |

“”Thanks for your telegram. I yesterday pointed out to your government the way by which alone war may be avoided. Although I requested an answer for noon today, no telegram from my ambassador conveying an answer from your Government has reached me as yet. I therefore have been obliged to mobilize my army.

|

| —Wilhelm II to the Tsar, several hours before declaring war.[144] |

Wilhelm and Germany fucked things even harder in the crisis leading up to the Great War. After the infamous assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, a diplomatic scramble-fest ensued among various European powers in the hopes of avoiding war. Although much has been made of the fact that Austria was the first to open the festivities, Germany was far from blameless in helping to begin the bloodbath. Despite knowing that all of Austria's actions were posturing in the hopes of manufacturing a further reason to attack Serbia over the assassination, Germany repeatedly assured the rest of Europe that it had things under control and that Austria wouldn't do anything rashly.[145] All of this bullshit was meant to give Austria cover in the hopes that if the war began unexpectedly, the allies would lack the resolve to immediately jump in.

The plan did not fall into place. Austria declared war on Serbia on the 28th of July, and when Germany immediately backed them, it became apparent that the Germans' talk of trying to keep the peace and restrain its ally had all been lies. The other powers of Europe, especially Russia, were pissed. The German ambassador to Russia recounted that the Russian Foreign Minister "now saw through our whole deceitful policy, he no longer doubted that we had known the Austro-Hungarian plans and that it was all a well-laid scheme between us and the Vienna Cabinet."[146]

The dominoes quickly fell into place after that, as each great power honored their alliances and joined the war. Germany found itself in the unenviable position of fighting a resentful Russia on one side and hated France on the other. The conflict also spread to Asia and Africa. Germanys primary Asian ally was the Ottoman Empire, whilst its primary African allies were Sultan Diiriye Guure's kingdom headquartered in Taleh, Abyssinian emperor Lij Iyasu, and the Darfur Sultanate. The Dervish Garadate of Diiriye Guure was the last of these to be defeated in 1920.[147]

Bloodbath[edit]

German leaders realized that being caught between two powers was a bad place to be. Their plan to avoid this had been proposed in 1905 by Alfred von Schlieffen, chief of the German general staff.[148] The Schlieffen Plan called for a rapid and overwhelming attack to defeat France while token forces held the line against Russia. Once France was out of the picture, the Germans could turn east. Instead of invading the German-French border, the Germans would advance through Belgium and turn south to catch France by surprise and capture Paris, forcing them to make peace.[149]

Although Belgium fell and German armies advanced through northern France, the promised knockout blow never materialized. Instead, France halted the German advance before they reached Paris in the First Battle of the Marne.[150] Both sides attempted to outflank each other before reaching the sea,[151] an unsuccessful maneuvering fest that left everybody staring at each other over a line of fortifications. You know where this is going. The advent of the machine gun and modern artillery meant that attacking an enemy formation with conventional 19th-century tactics (like everybody had been doing) was tantamount to suicide. Soldiers dug into the ground for safety against each other's deadly firepower, rapidly developing into the infamous trench warfare system.[152] By October 1914, none of the armies could make any meaningful advances, and by the end of the year, about 475 miles of trenches had been built across the entire length of the Western Front.[153]

Invading Belgium also gave Britain (by treaty the guarantor of Belgian neutrality) a sufficient excuse to rally the already anti-German populace to support war. From late 1914 onwards, the British Royal Navy blockaded the English Channel and the North Sea entrances, hoping to starve Germany and Austria into submission.[154] The impacts on the Central Powers were immediate, and civilians started to suffer food shortages as early as 1916. Both sides used submarines against merchant shipping, as submarines were undetectable but too fragile to compete with surface warships.[155] British shipping defended itself by flying the flags of neutral countries, which caused Germany to declare its policy of allowing its submarines to sink neutral shipping. Foreign reaction to unrestricted German warfare was very negative, especially after the Germans sank the RMS Lusitania, (which seemed to be) a passenger ship.[156]

Meanwhile, Germany steamrolled the Russians, causing horrific suffering and an enormous refugee crisis. German scientists also introduced chemical weapons in the form of poison gas, further increasing the suffering of trench warfare. Germany's African colonies were quickly overrun by France and the UK. The British blockade of Germany's ports, which Germany's great navy had been unable to breach, made matters much worse. The winter of 1916-1917 was horrific; German civilians called it the "Turnip Winter" as the potato crop had failed, and they were forced to eat rutabagas instead.[157] The entry of the United States into the war, brought about by anger against the German submarine campaign, made victory seem impossible. Starvation and hopelessness combined with the deaths of 2,037,000 German soldiers created a demographic, political, and humanitarian emergency for Germany.[158]

German Revolution[edit]

Things came to a head in 1918 when sailors in Kiel refused to take part in a planned final strike.[159] When the mutineers were arrested, this spiraled into a massive protest involving sailors and civilians. Protests quickly spread across the country. By November, the revolutionaries had bagged themselves a monarch, forcing the king of Bavaria to flee Germany and proclaiming a "People's State" in his absence.[160] On the 9th of November, the new German Chancellor Max von Baden announced the Kaiser's abdication, entirely to the Kaiser's surprise.[161] On the advice of Paul von Hindenburg, however, the Kaiser accepted that the loss of his crown was inevitable, and he left for exile in the Netherlands.[161]

After the armistice, Max von Baden found himself unable to negotiate a lasting peace. He resigned and illegally handed the reins to Friedrich Ebert.[161] Ebert's colleague from the German Social Democratic Party, Philipp Scheidemann, went behind his back to declare Germany a republic.

Meanwhile, the more radical elements of the Social Democratic Party created the "Spartacus League", led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg. This kicked off about a year of communist uprisings in Germany, featuring warfare between the Spartacists and the Freikorps of right-wing war veterans assembled by the government in response.[162] The Freikorps, battle-hardened and armed with modern rifles and machine guns, were ruthlessly effective and merciless in putting down the uprising and summarily executing Luxembourg and Liebknecht.

Treaty of Versailles[edit]

After the Kaiser was gone, the German diplomatic corps simply agreed to whatever terms the allies wanted for an armistice.[163] The Germans, now with a new government and the old warmongers tossed out, expected peace would be relatively lenient for them, probably taking place within the framework of Woodrow Wilson's "Fourteen Points" plan. The other European powers promptly tossed out Wilson's plan and proceeded with harsh terms against Germany, as most of the Entente not only demanded compensation from Germany for their wartime suffering but had also made secret treaties with other countries about how Germany would be split up.[164]

The Germans were shocked by the treaty's terms, as they had been assured a relatively soft peace in return for the truce.[164] Germany was forced to cede Alsace-Lorraine back to France, allow the Saarland to be placed under military occupation, cede some areas to Belgium, cede northern Schleswig to Denmark, cede parts of Silesia and West Prussia to the resurrected Poland, and lose its colonial holdings to France, the UK, and Japan.[164] Germany was then forced to demilitarize. A "war guilt" clause also declared Germany the primary aggressor in the war and made them responsible for paying reparations to the Entente powers. This last part caused much anger among the Germans, although the Entente powers subsequently agreed to lessen and indefinitely postpone the payments.[165]

In the end, the treaty was neither lenient nor harsh enough to prevent another war. Germany was not pacified by a light-handed peace nor weakened enough by the territorial losses inflicted upon it. The Entente powers themselves realized that the agreement had problems. British representative John Maynard Keynes predicted that the treaty's reparations clause would inflame German revanchism, while French Marshal Ferdinand Foch criticized the treaty for treating Germany too leniently.[165]

Weimar Republic[edit]

“”Now we have a Republic, the problem is we have no Republicans.

|

| —Walter Rathenau, first Foreign Minister of the Weimar Republic.[166] |

Interwar misery[edit]

Born out of revolution and wartime carnage, the Weimar Republic was perpetually unstable from the beginning. The republic gets its name because its constitution had to be adopted in the city of Weimar rather than Berlin, as Berlin was occupied by the Spartacists at the time.[167] Alongside the communist uprisings, conservatives attempted to overthrow the government in 1919 in the hopes of re-establishing the monarchy and reversing the revolution.[168]

The new republic's constitution had a powerful president, seen by many as a substitute Kaiser. The president was elected by popular direct ballot to a seven-year term and could be reelected. He appointed the chancellor and cabinet ministers, and could dissolve the Reichstag and govern without its consent.[169] You should remember that last bit since it would cause some major problems down the road.

Compounding the republic's political instability was the problem of hyperinflation, which plagued Germany due to the government's short-sighted policy of printing money to make reparations payments.[170] Even then, Germany had issues meeting the requirements, so France sent angry troops to occupy Germany's industrial Rhineland to take control of the factories and confiscate goods.[171] German passive resistance to this was met with gunfire and expulsions. Hyperinflation caused a total collapse in Germany's currency, to the point where by 1923, the US dollar was worth an absurd 4,210,500,000,000 German marks.[172]

Germany's reconstruction began under chancellor Gustav Stresemann, who was the architect of its foreign policy for much of the early republic. Stresemann successfully negotiated reduced reparations payments and managed to get the French occupation forces withdrawn from the Rhineland by promising to keep the region demilitarized.[173] This was some truly skilled statesmanship, but it pissed off the rightists who thought that Germany should take everything by force because the world owed it. To them, the republic's diplomacy, as well as its very existence, was an unacceptable betrayal of everything it was to be German.

A sabotaged democracy[edit]

The republic quickly became a failed government, with most of the population having no faith in it. The far-left, for instance, regarded the republic as a tool of the moneyed bourgeois to keep the poor under control, bitterly remembering the republic's role in putting down the Spartacist uprising.[174] The left, however, was too disorganized and weak to pose a real threat to the republic.

No, the real threat came from the right, who hated the republic's democratic principles and longed for a return to the old conservatism and comfort of an absolute monarchy. Or, failing that, an absolute dictatorship. The right was so dangerous because it enjoyed the support of most of Germany's establishment: the military, the financial elites, the state bureaucracy, the educational system, and much of the press.[174] Right-wing parties in the Reichstag openly hoped to dismantle democracy and place Germany back on a path of militarism. Political violence and assassinations were prevalent, mainly acts perpetrated by the far-right.[175] Right-wing parties managed to influence judicial appointments and said judges would promptly let right-wing terrorists off with negligible sentences while harshly punishing leftists.[174]

On the other hand, the republic did allow a brief flourishing of German cultural life. After the chaos of the postwar period settled down, Germany had its own modest version of the "Roaring Twenties." Social liberals in the big cities could live freely, with sexual liberation movements, homosexual establishments, and a thriving nightlife being notable.[176] The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, run by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, produced large volumes of work analyzing and humanizing homosexual and transgender people.[177] This also somewhat extended to social life, with cabaret dancer Anita Berber becoming popular and scandalous due to her androgynous acts and her public admission of being bisexual.[178] Women also experienced a brief liberation era, being given the right to vote for the first time in German history.

Sadly, the liberalization of Germany in the cities only further fueled right-wing fury, who were disgusted with what they saw.[176] Much of the progress made during this era, especially that promoted by Dr. Hirschfeld's institute, was viciously attacked by the Nazis.

Rise of evil[edit]

Meanwhile, a little Austrian-born fuckhead named Adolf Hitler, lacking any real-life skills, stayed with the army and joined the subversive and fascist German Worker's Party (DAP) to spy on it on behalf of the German government.[179] He very quickly became enchanted by its message of antisemitism and expansionist nationalism. He joined it and led it to rebrand as the National Socialist German Worker's Party (NSDAP), which would be better known as the Nazi Party. Hitler designed the party's swastika emblem, which has been used as a symbol by and for shitheads in the West ever since.[180] He then left the army and became notorious for giving rowdy and angry speeches to any group of people who would listen. By 1921, the Nazi Party recognized Hitler as one of their most influential public figures, and he was elected Party Chairman.[180] In late 1923, Hitler tried to launch the laughably failed Beer Hall Putsch in Munich, which landed him in prison for a few months.[181] From there, he wrote his shitty book Mein Kampf, which, along with the Great Depression and the resultant misery, caused the Nazi Party's popularity to explode. He presented a deranged fantasy world in which Germany was at war with the Jews running the capitalist system and simultaneously running the Soviet Union. According to him, it had also been the Jews who had sabotaged Germany in the last war.

Eventually, the increasingly popular Nazi Party started to win enough votes to cause deadlock in the Reichstag. Germany held presidential elections in 1932, and conservative Paul von Hindenburg ran against Adolf Hitler and the communist Ernst Thälmann. Hindenburg received broad support due to Hitler's extremism; traditional conservatives backed him, and liberals endorsed him as the lesser of two evils.[182] As a result, Hindenburg handily won the election. Unfortunately, more political deadlock set in, leading Hindenburg's conservatives to take the extraordinary step of encouraging the president to appoint Hitler as chancellor.

The Third Reich[edit]

“”Every national voluntary association, and every local club, was brought under Nazi control, from industrial and agricultural pressure groups to sports associations, football clubs, male voice choirs, women's organizations — in short, the whole fabric of associational life was Nazified. Rival, politically oriented clubs or societies were merged into a single Nazi body. Existing leaders of voluntary associations were either unceremoniously ousted, or knuckled under of their own accord. Many organizations expelled leftish or liberal members and declared their allegiance to the new state and its institutions. The whole process... went on all over Germany... By the end, virtually the only non-Nazi associations left were the army and the Churches with their lay organizations.

|

| —Richard Evans, The Third Reich in Power.,[183] |

Flag of the Waffen-SS.

Consolidation of power[edit]

With so few people willing to defend the republic's institutions, Hitler had no trouble turning Germany into a totalitarian dictatorship. Shortly after Hitler became chancellor, the Reichstag building burned down under mysterious circumstances. Hitler and the Nazis promptly pinned the crime on a random communist and used it to justify the passage of the Reichstag Fire Decree.[184]

The decree suspended essential parts of Germany's constitution, removing the right to assembly, freedom of speech and freedom of the press and giving the German police the power to do whatever they wished.[185] It also gave Hitler the power to dissolve and overrule local governments, ban publications, and jail people without charge (removing the right of habeas corpus). Hitler then mobilized Nazi Party paramilitaries inside the Reichstag itself to force the parliament to pass the Enabling Act,[186] which granted Hitler the power to pass laws without consulting anyone else.